Story 1: Jasmine

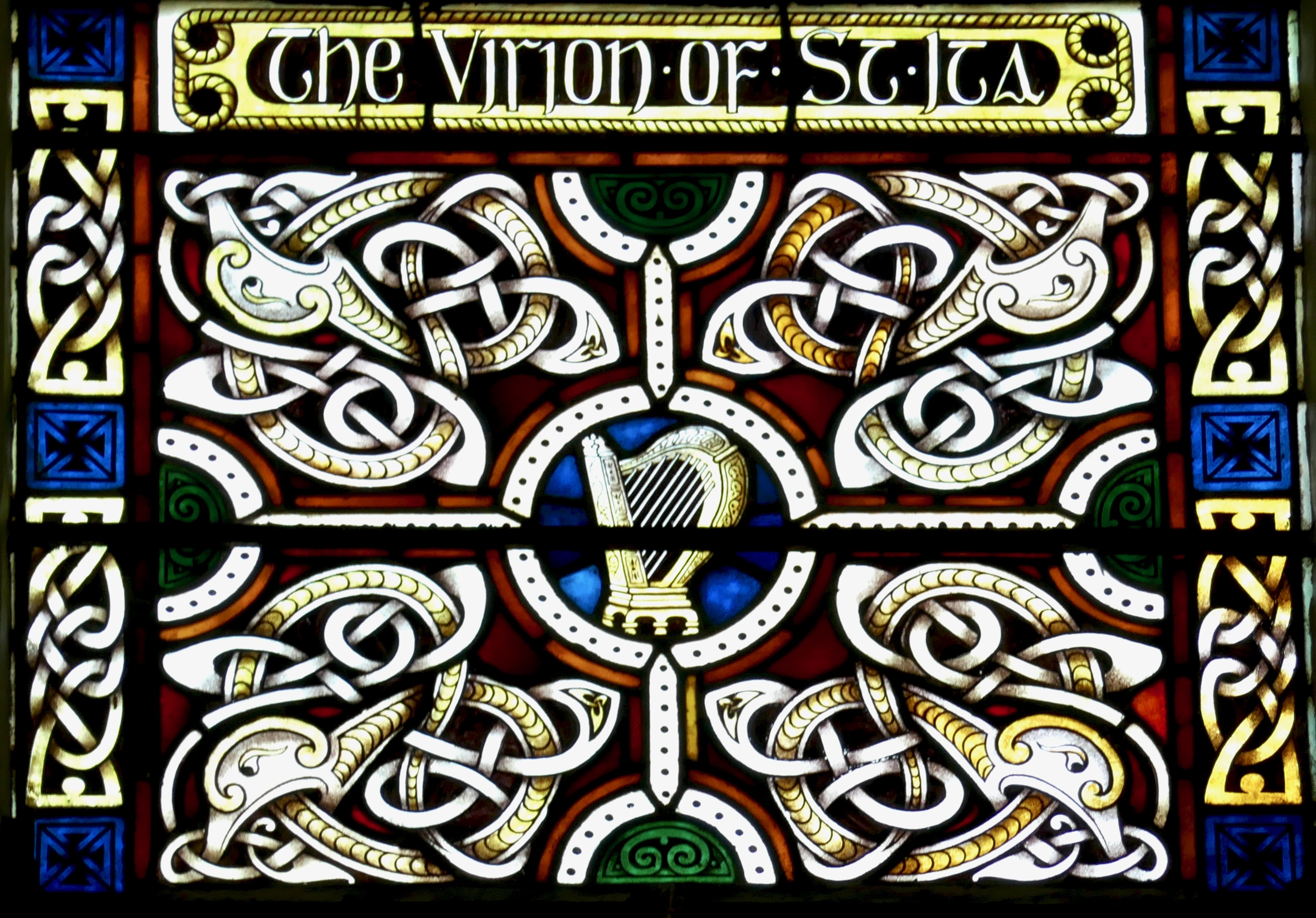

The first story concerns Jasmine Allen – she is the charming and erudite Curator of the Stained Glass Museum in Ely, in the UK. At a recent Stained Glass Symposium in Trinity, she showed us how stained glass studios were advertising their artistry and products at exhibitions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Britain and Ireland, starting with the Great Exhibition in 1851, but happening at regular intervals after that. The Irish International Exhibition was held in Dublin in 1907. It was inspired by the success of the Cork International Exhibition of 1902 (see Robert’s post about that here) and even copied their thrilling water slide! For a marvellous collection of images from that exhibition, see this Flikr Album from the Church of Ireland. The story of their discovery is also fascinating.

Irish international exhibition from Herbert Park, by National Library of Ireland on The Commons

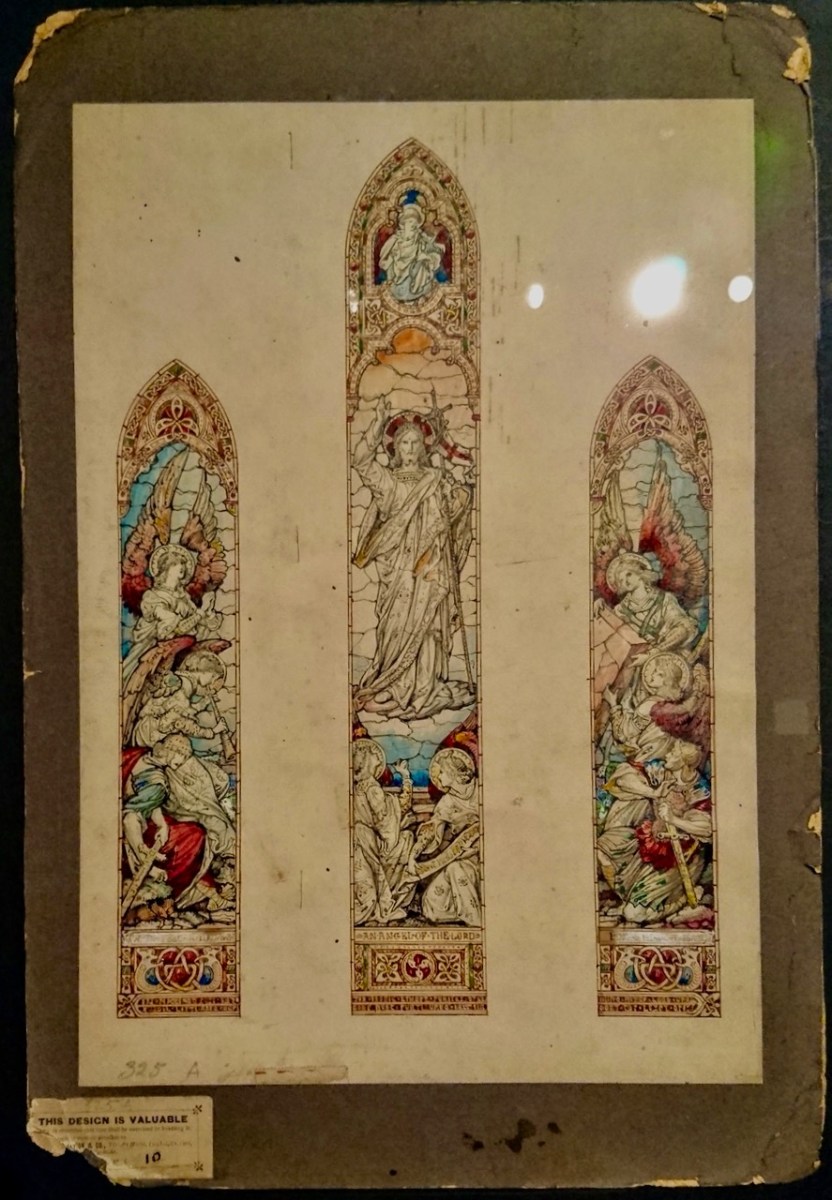

One of the exhibitors was James Watson and Co of Youghal. Jasmine subsequently sent me this image, saying: Catalogues of these exhibitions are all too brief and I would love to know what happened to it. Is it in a church or secular building in Clontarf? I only have a very bad image from the Art Journal (early b+w photography was worse than engraving for capturing stained glass!)

Story 2: Michael

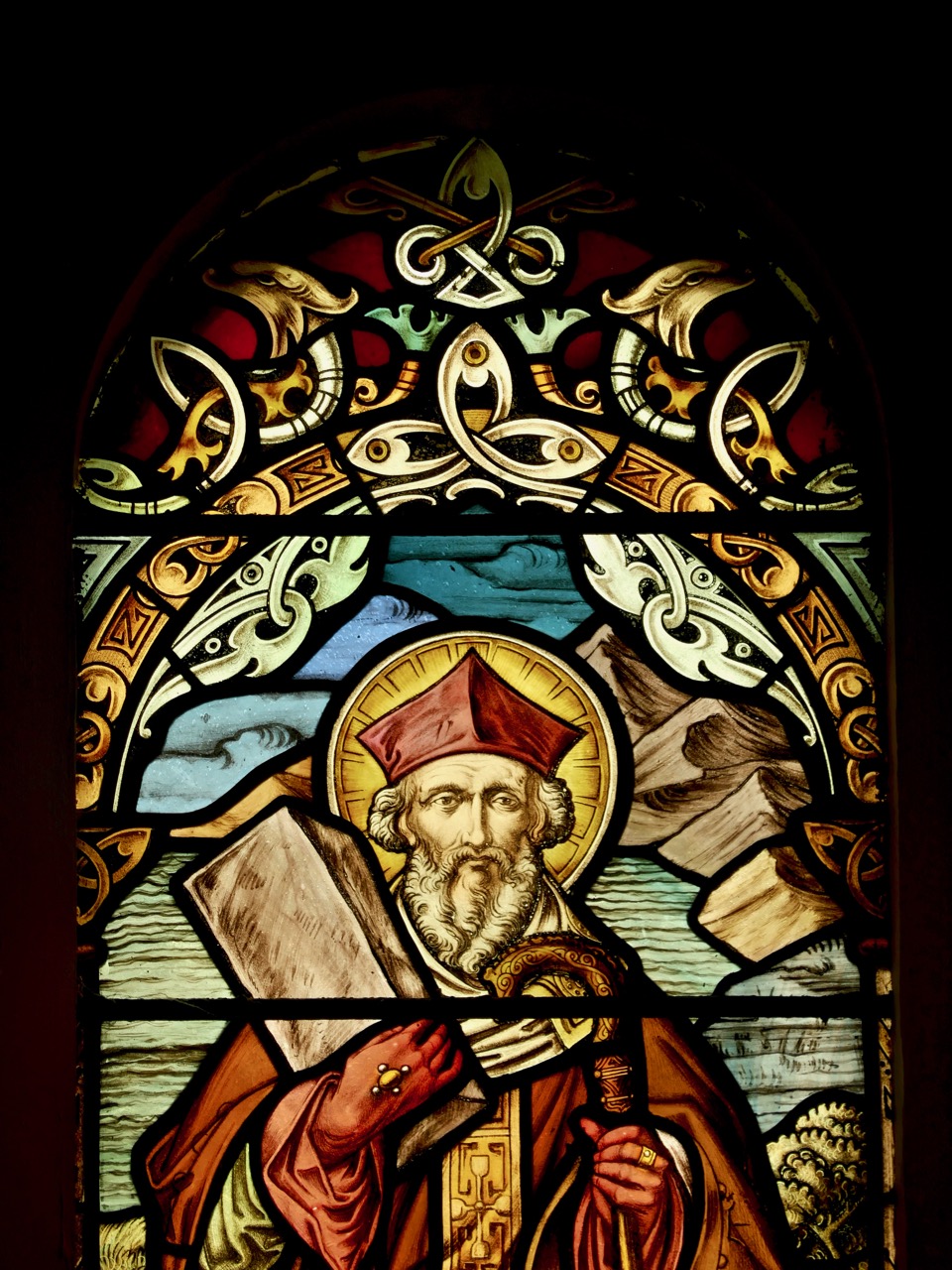

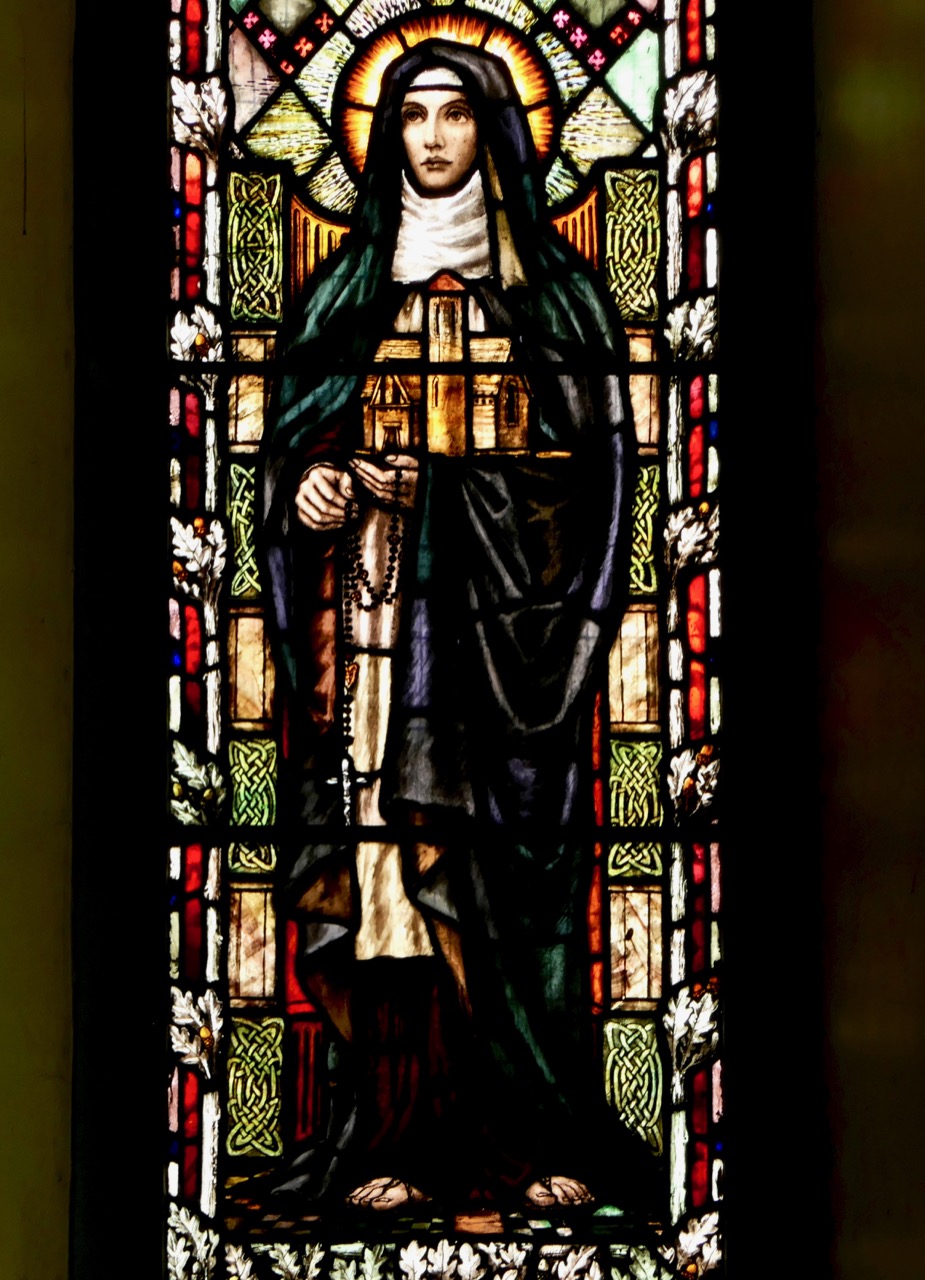

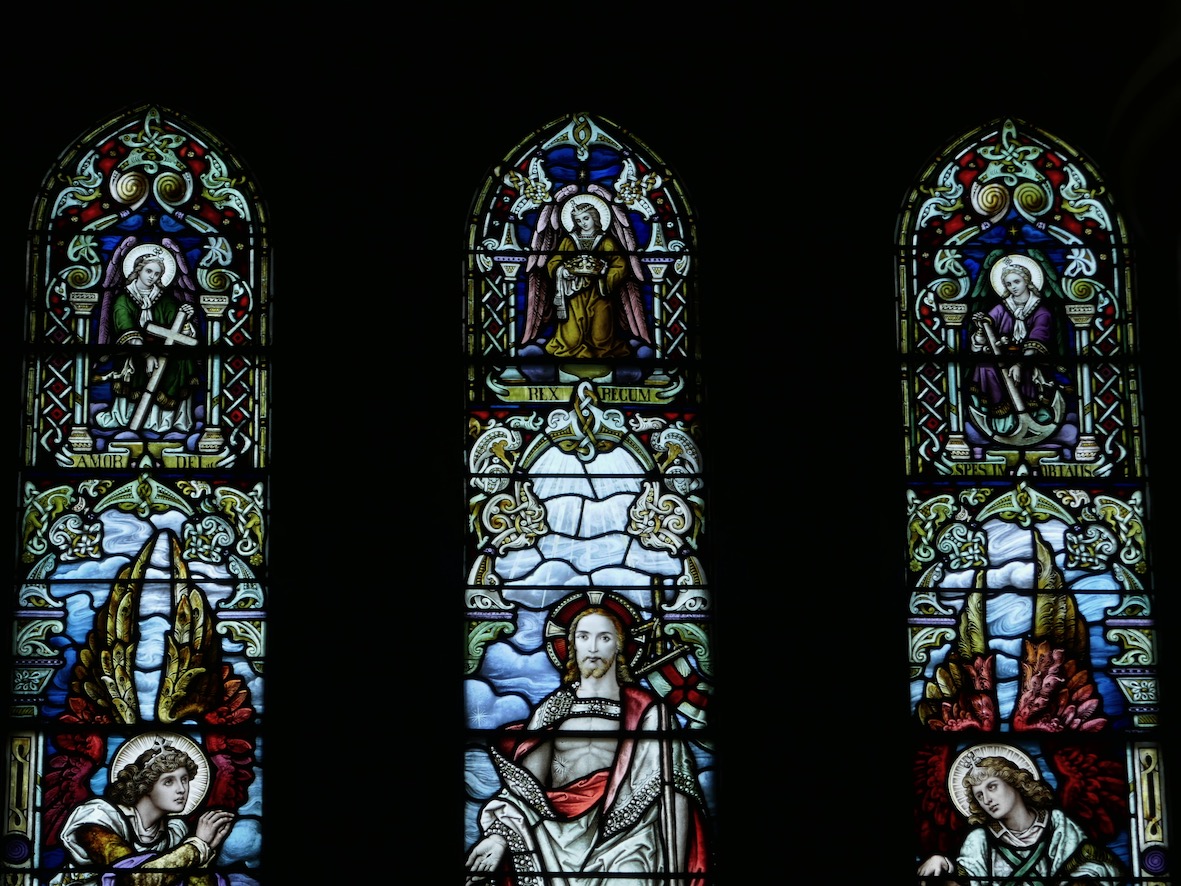

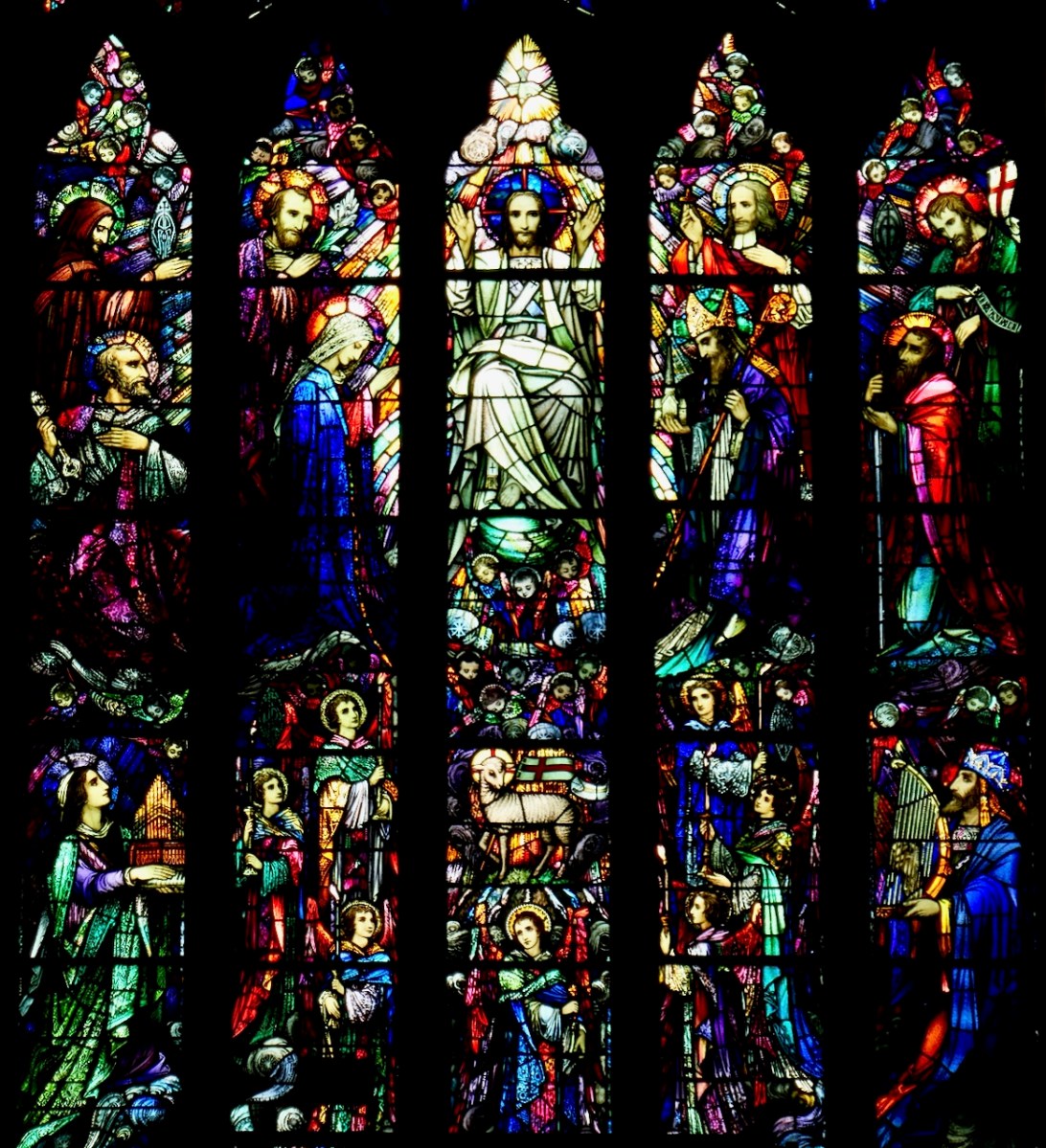

I sent the photo to the group of colleagues, mostly contributors to the Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass with whom I correspond on a regular basis and who are always helpful, asking if any of them knew the fate of the window. I got several “no idea” responses and then I heard from Michael Earley. Anyone interested in Irish stained glass will be familiar with the name of Earley, and Michael Earley, a great-grandson of the founders, has just completed doctoral studies on the Studios. I’ve featured Earley windows here and there in my blog posts, but here’s an example of their work – you will find it everywhere throughout Ireland, often distinguished by glass of unique and brilliant colour, enormous packed scenes of multiple angels and saints surrounding a central images, and beautifully rendered figures. Here’s one from St Aidan’s Cathedral in Enniscorthy.

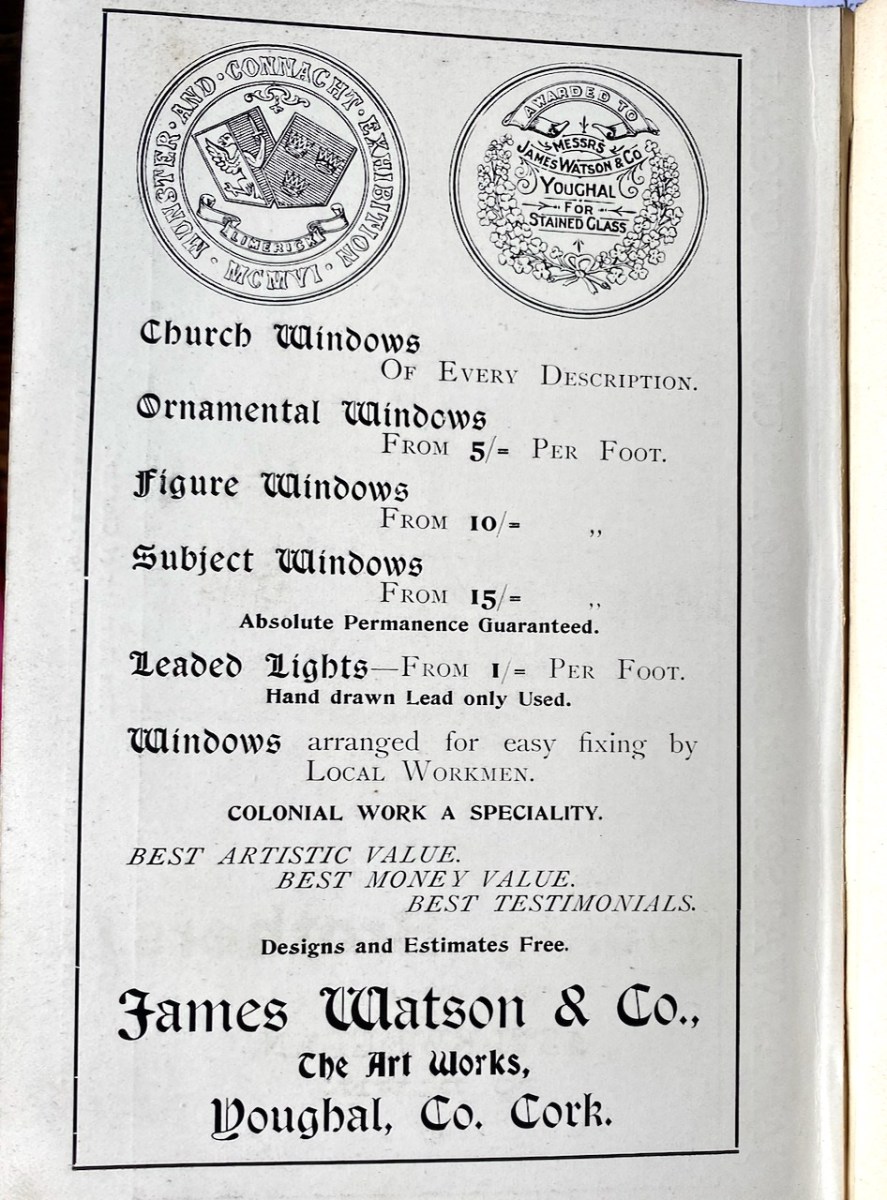

Michael didn’t know what had happened to the window, but he did send me two pages from the Irish Catholic Directory of 1908. The first page was an advertisement for James Watson and Co, The Art Work, Youghal, Co. Cork. Here it is:

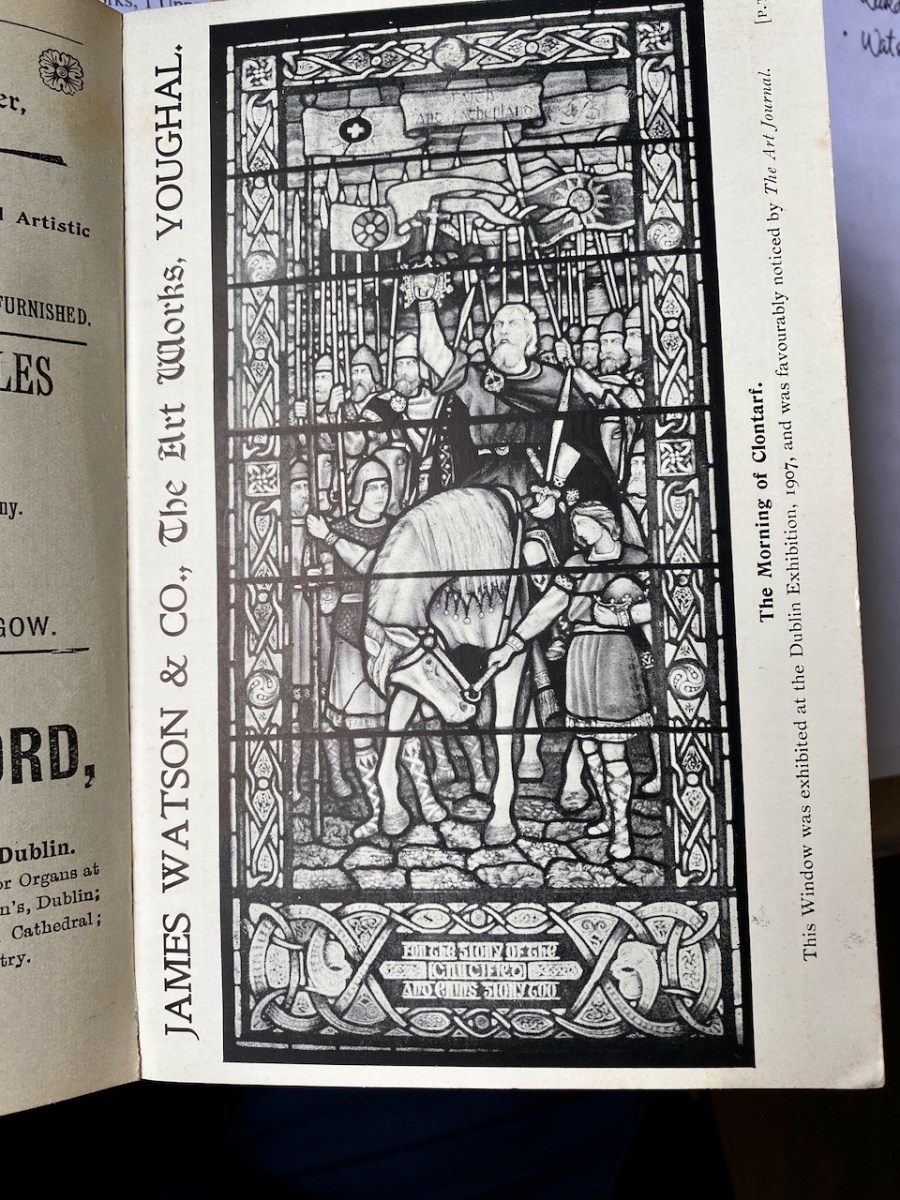

Much to savour in this ad – the prices, the variety of windows, “colonial work”. . . The second page, though, hit the jackpot. It was from the same Directory, and was a full scale black-and-white photograph of the window. Titled The Morning of Clontarf, a subtitle reads “This window was exhibited at the Dublin Exhibition, 1907, and was favourably noticed by The Art Journal”.

Now I had an excellent image with which to pursue my inquiries – and I knew exactly who to consult!

Story 3: Vera

The art historian who knows more than anyone else about Watson of Youghal is Vera Ryan. In fact, it was Vera who curated the Crawford Gallery 2015 exhibition of the Watson Archive, when the Crawford acquired the Archive. She also wrote the piece on Watsons: Divine Light: A Century of Stained Glass, in the Summer 2015 edition of the Irish Arts Review. A couple of years ago, when I was trying to find information on a Watson window which was the centrepiece of an article I was writing for the Clonakilty Historical and Archaeological Journal (now published and available here), Vera mentored me as I tried to dig my way through the archive. We have been exchanging information ever since.

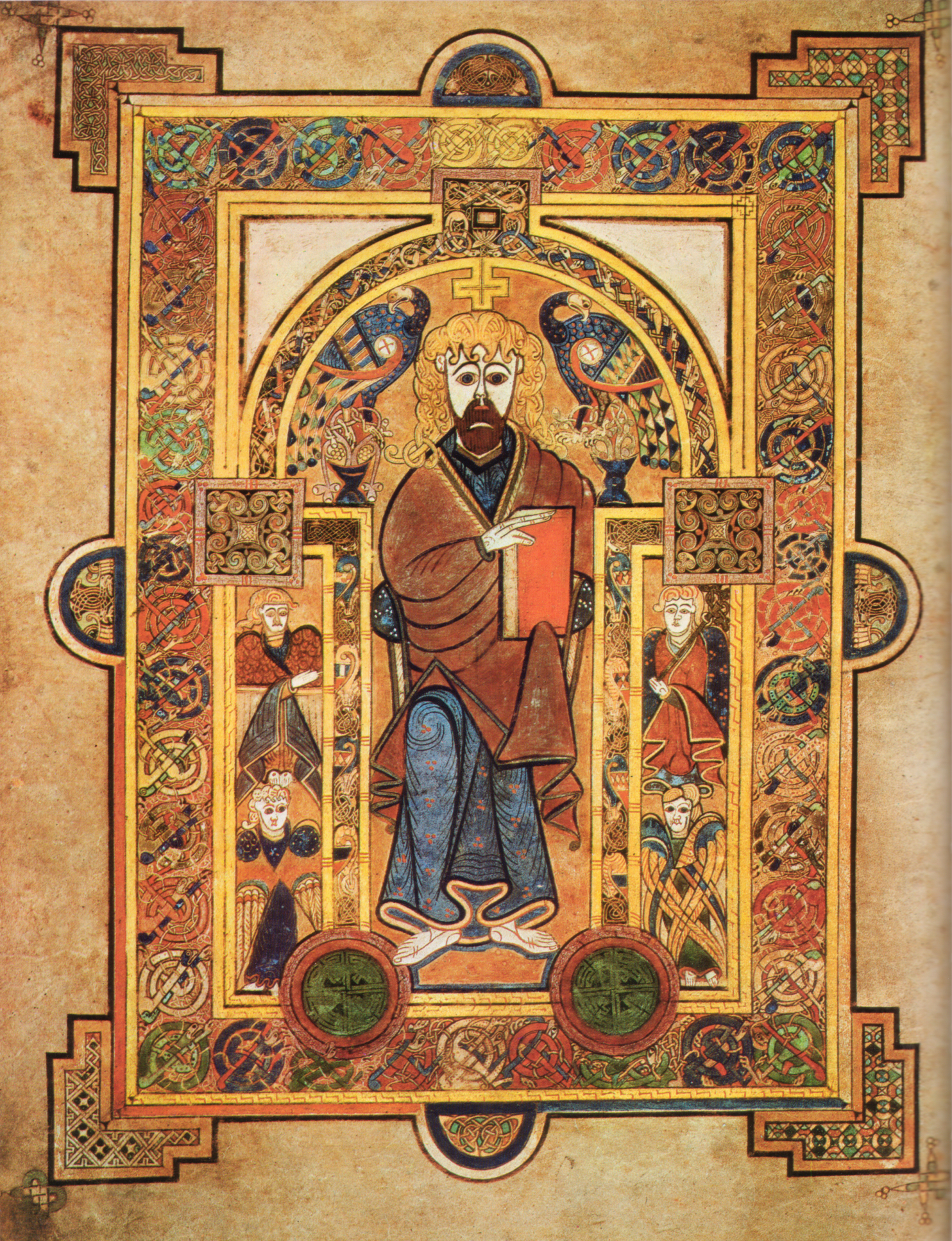

Above is a window in St Michael’s Church, Tipperary, erected in 1914. The design (below) and cartoon (below below) for this window were still in the Watson Archive and were displayed in the Crawford Exhibition. This represents a special opportunity to see the evolution of a stained glass window from concept to completion.

This opportunity is relatively rare in stained glass studies – there aren’t many collections like this, so it is wonderful that the Crawford rescued the archive, which has now been passed on for expert conservation, to the National Gallery of Ireland.

When I contacted Vera, she remembered the Brian Boru window well, and told me that the cartoon was part of what came to the archive, although in a very fragile state. The window, itself, she thought, was still extant, and possibly in Knappogue Castle. The important person to talk to, she said, was Antony Watson, great-grandson of James Watson and the executor of the Watson Estate. Before I did that, I tried some detective work of my own.

Story 4: Jody

I don’t know Jody Halstead, but in 2016 she stayed at Knappogue Castle and posted a video to YouTube, titled The Knappogue Castle Most Visitors Don’t See. At about the 5 minute mark she arrives at a landing and as her camera roams around, it captures a stained glass window – and there it was! Here’s a screenshot from the video.

Because of Jody, now I had proof that the window was still in existence. The next challenge was how to get a good photograph of it. Once again, thanks to the glorious (and relatively small) world of Irish stained glass scholars and enthusiasts, I knew who to turn to.

Story 5: John

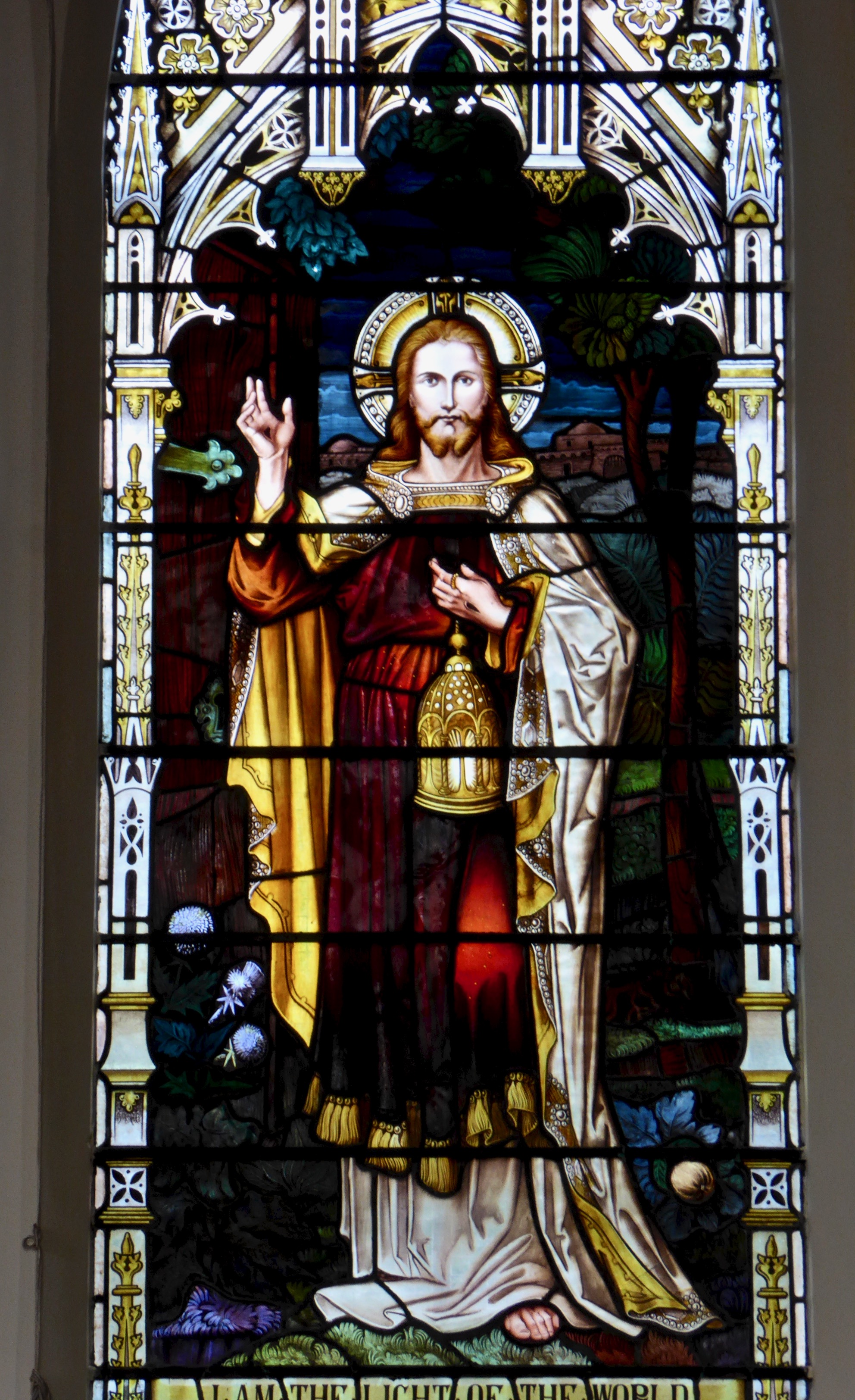

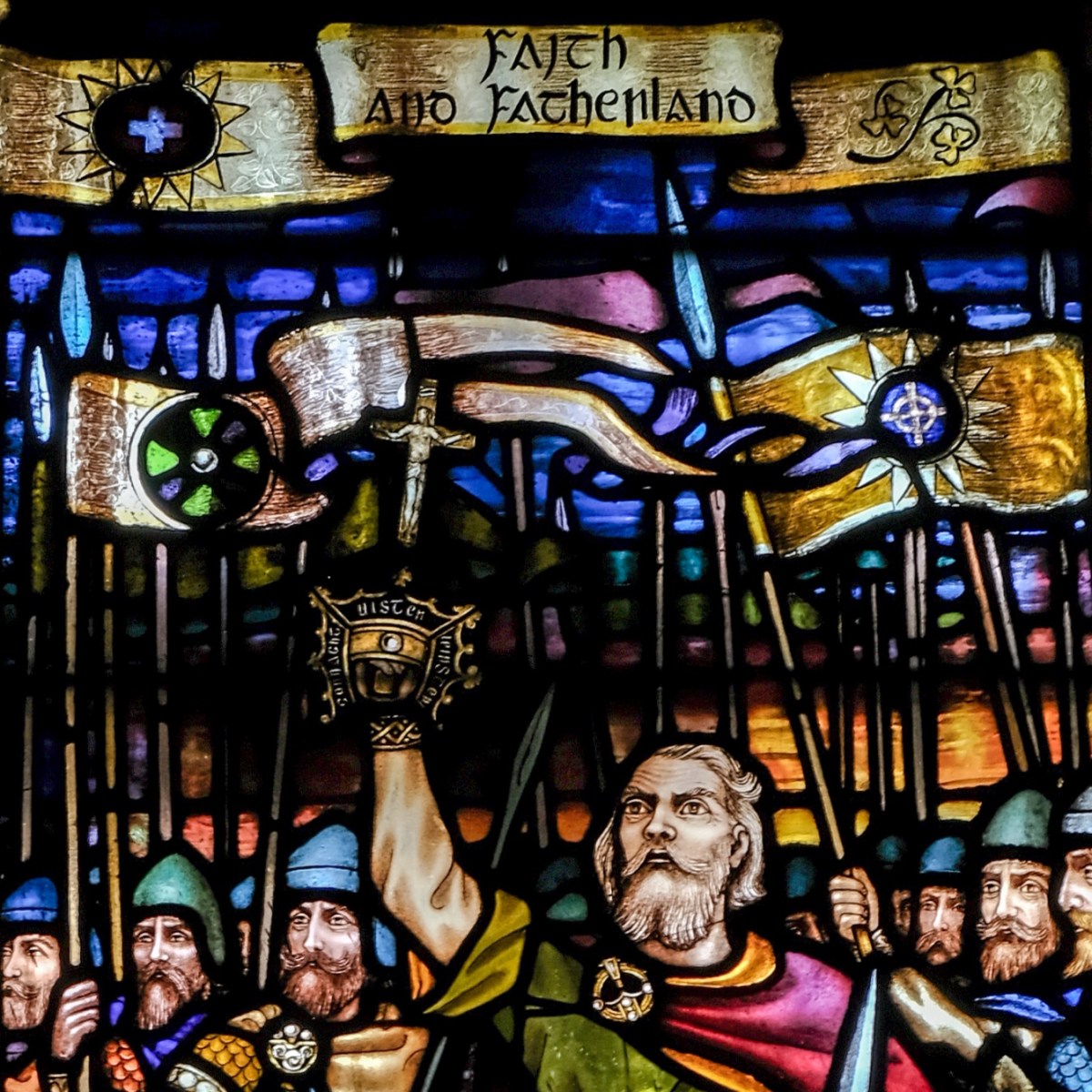

John Glynn is an outstanding photographer with an interest in stained glass. His was the excellent image from Kilrush I used in my post on Brigid: A Bishop In All But Name, and he lives in West Clare, about an hour by car from Quinn, where Knappogue Castle is located. I thought he might already have taken a photograph of the window – he hadn’t but promised to do so as soon as he could. To my great delight, he did it right away. Here is what he sent me.

This and all detailed images of the Brian Boru window in Knappogue, are the work of John Glynn, and used with his permission

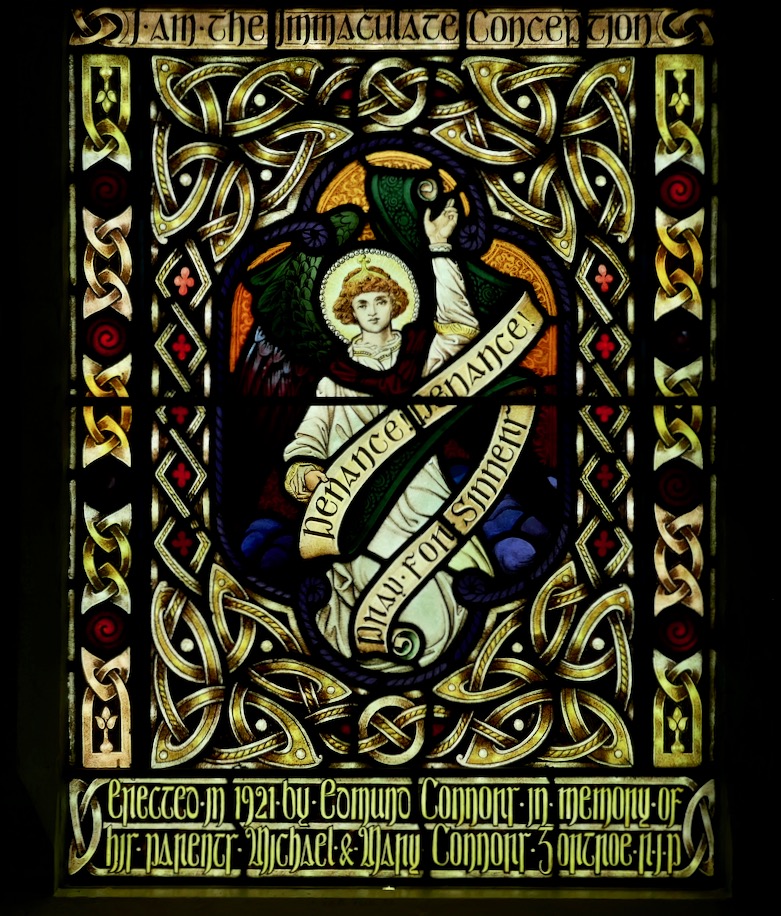

Isn’t it an amazing photograph! What’s also clear in this photograph is that the window is incomplete. To make it fit the opening, the predella, or bottom section, has been removed. Here’s what’s missing.

The text, in old Irish script, reads FOR THE GLORY OF THE CRUCIFIED AND ERIN’S GLORY TOO. The Celtic Revival interlacing that surrounds it is beautiful, and accomplished – it’s the thing that Watson’s were to become most famous for. So that’s a loss. Perhaps it was felt that the script was not suitable for a secular building: however it is more likely that it had to go in order to make the window fit. The rest of the window, comparing it to the original black and white images, seems to be intact. I was curious as to how the window came to be there, and this brings me to my second-to-last story.

Story 6: Antony

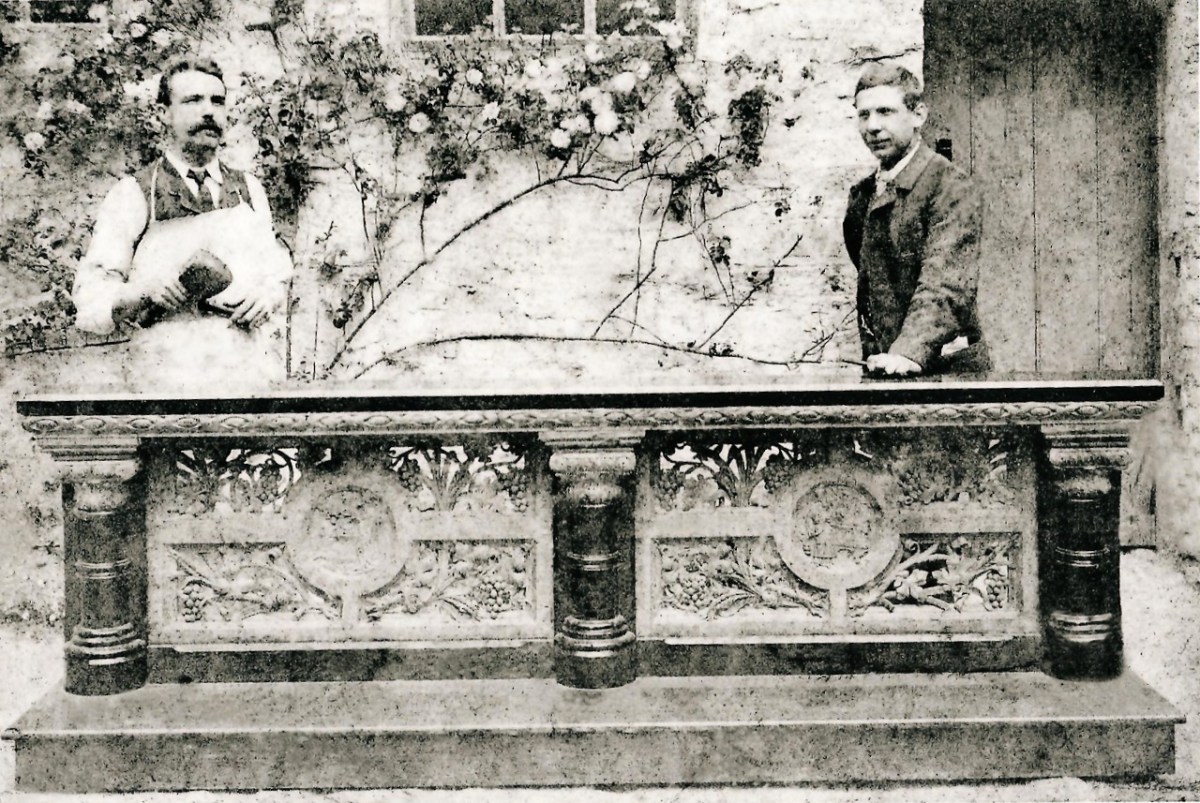

Vera kindly put me in touch with Antony Watson, and yesterday we had a long talk on the phone. Antony’s father was John Watson, Manager and Chief Designer for Watson of Youghal. John’s father was Clement, universally known as Capt Watson (he was an officer in the RFC/RAF), and Clement’s father was James Watson, seen here with a marble altar carver.

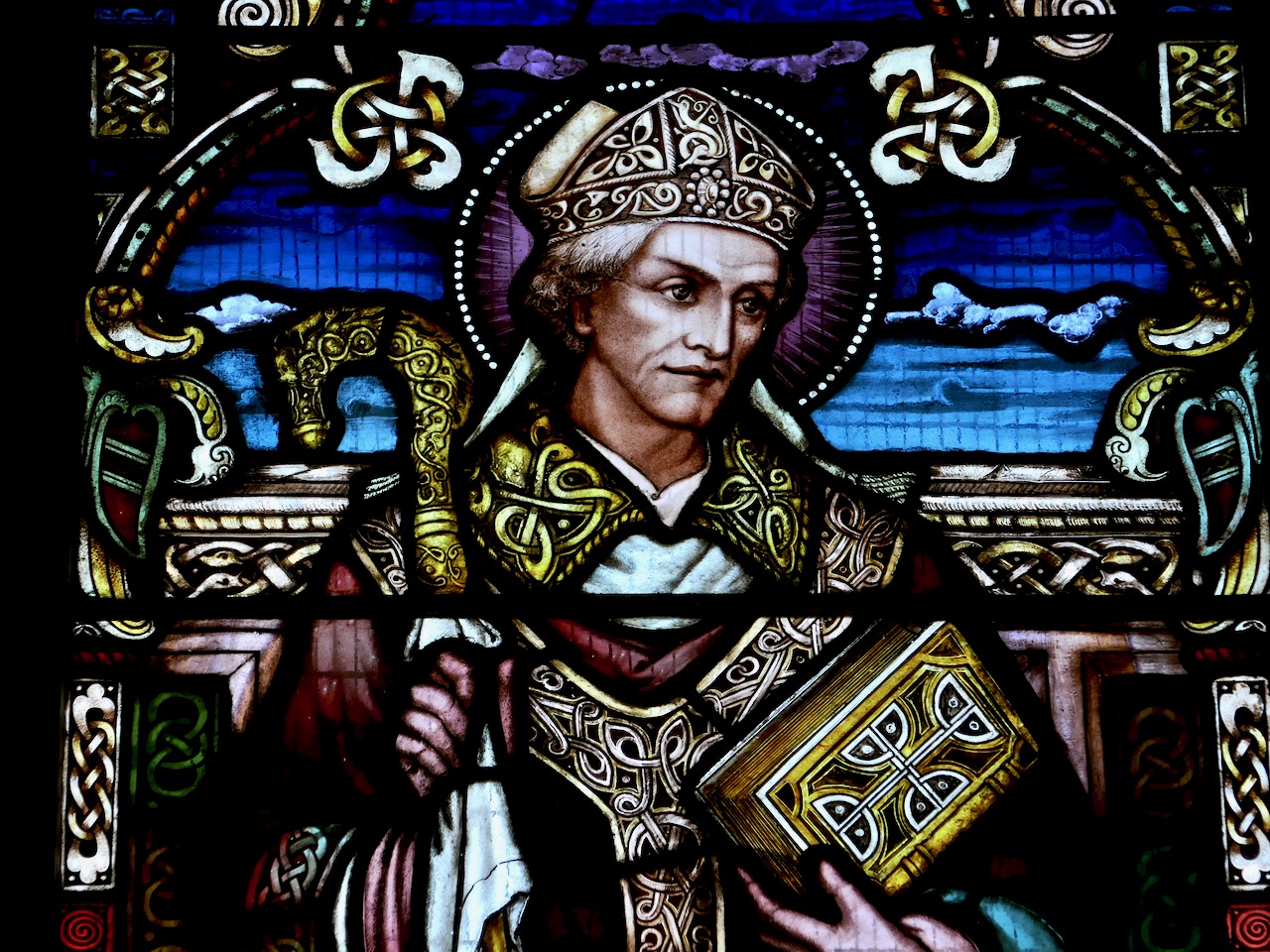

James had come from Yorkshire to run the Irish office of Cox, Sons, Buckley & Co, Church Outfitters, and eventually bought the Irish branch of the company. Here’s one of their early windows, in Ballingeary, from the 1880s, when they were still being signed as Cox, Sons, Buckley, Youghal and London.

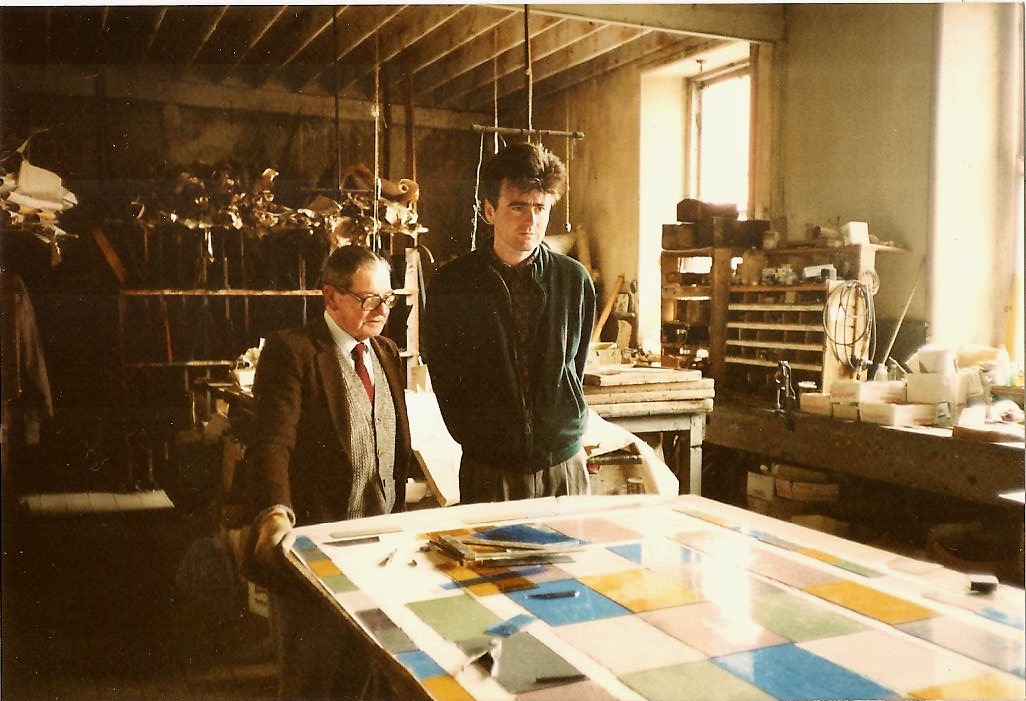

Antony told me the most enthralling stories, and I want to devote more posts to cover some of that treasure trove in the future, but I don’t want to get too distracted from Brian Boru now. Antony loved his life in and around the studios and workshops when he was young and has a very clear memory of the Brian Boru window. It stood, he said, in a rack in what was called the Great Hall (a grand name for a storage area for tall items). Here’s Jack, Antony’s father, with a client, in the early 1990s.

Watsons got the job of installing leaded windows into Knappogue Castle when it was bought by wealthy Americans – Mark and Lavonne Andrews. He remembers the day they arrived to see the Brian Boru window – there was a frantic tidy-up beforehand and the whole of Youghal turned out to witness two stretch limos arriving in state and disgorging the ‘Texas millionaires’ and their retinue.

Story 7: Mark and Lavone

This is Mark Edwin Andrews, highly educated (Princeton) and cultured, and at one time Assistant Secretary of the Navy under Truman. He went on to become an industrialist and oil producer. His wife, Lavone Dickensheets Andrews (so sad I can’t find a photograph of Lavone) was a prominent architect. Together they purchased Knappogue Castle in 1966 and set about restoring it from a ruinous state. Knappogue is located in Quinn, Co Clare, the heart of Brian Boru country. It’s now owned and managed by Shannon Heritage.

It was Mark and Lavone who rescued the Brian Boru window and had it fitted into Knappogue Castle, some time in the 1970s. And there it still is, a testament to the enduring attraction (and durability) of stained glass windows and their power to enchant and intrigue us.

It’s a highly unusual window in so many ways, not least that it is a secular rather than a religious subject. It showed off, when it was exhibited, one of our historic heroes, Brian Boru (for more about Boru, see Robert’s post, Battling it Out), as well as the Celtic Revival decoration which Watsons mastered: both the subject matter and the treatment established them firmly in the Nationalist Camp. This of course, was a canny move designed to appeal to Irish Catholic church-builders. Antony tells me that nobody espoused Irish Nationalism more enthusiastically (or astutely) than James Watson, in the broad Yorkshire accent he kept to the end.

As an image of Faith and Fatherland, this window knew exactly who it was appealing to. It appeals to us still.