I had the great pleasure yesterday of co-leading a walk through Myross Woods, along with Mark Robins and Conor Buckley. Mark (that’s him above) is an ecologist, now retired to West Cork (and lucky we are to have him) and Conor is the dynamo who runs Gormú Adventures and who has an inexhaustible store of folklore, mythology, and local history. My job was to talk about the wildflowers, Mark set the context by explaining what a healthy woodland habitat looked like, and Conor enriched all the narratives with local lore.

So where, and what, exactly, is Myross Woods? It’s a large House on an estate of the same name, built originally in the mid-eighteenth century by the local Vicar, Arthur Herbert, who sold it eventually to the Earl of Kingston who was building Mitchelstown Castle and needed a place to live while it was under construction.

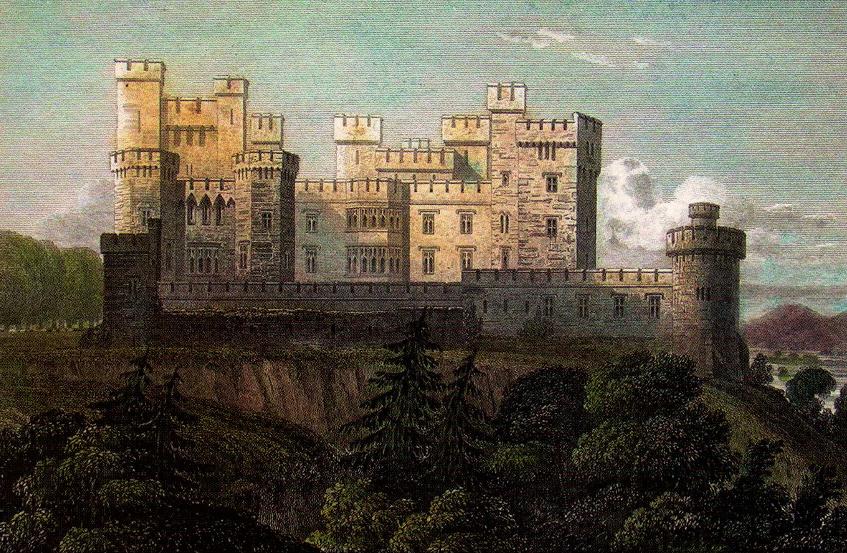

Mitchelstown Castle was one of the most impressive Castles ever built in Ireland. It was looted and burned by the IRA in 1922.

Mitchelstown Castle. Originally published in 1820 in “Views of the seats of noblemen and gentlemen, in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland.”, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16264046

It was probably the Earl who set about designing the landscape as a series of vistas and pleasure gardens to impress his guests – his guiding principle seems to have been that ostentation should be given priority (he specified that Mitchelstown Castle should be the biggest in Ireland). The eighteenth century was the era of the Designed Landscape. As I said in my post on Belvederes

The effect they strove for was naturalistic (as opposed to natural) – a planned layout that mirrored but enhanced their idea of a ‘wild’ and romantic landscape. Large expanses of grass, strategically placed lakes and ponds, plantings of carefully chosen tree and shrub species, and clever little structures such as temples, summer houses and belvederes all combined to delight the eye, create a romantic mood and, of course, attest to the taste and wealth of the owner.

Capturing the View: Belvederes in West Cork

One of Kingston’s enhancements was to carve out the rock to create a waterfall. I wonder how he and his Protestant guests would feel if they knew that the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, who ran Myross Woods as a retreat house for most of the twentieth century, had turned his sylvan feature into a Marian Grotto.

In the case of Myross Woods there is good evidence that there was an existing and ancient woodland, since some of the indicator species are present. Believe it or not, one of those species is the native Bluebell (Hyacinthoides non-scripta), which flourishes in ancient woods. Another is the Woodrush (ditto, above) which is identified with oak forests, such as we have at Myross Woods, as well as Wood Sorrel (above).

Kingston set about enhancing the environment by planting Beech Trees, by carving out clever little waterfalls, by building an impressive entryway featuring a hand-hewn tunnel, by walling a garden behind the house, and by all the interventions that were used at the time to create imposing carriage drives, romantic vistas and delightful walks.

As you can see above, the 1840s map and the modern map illustrate that the woods have remained more or less as they were, in terms of location and extent. It’s the composition of the woods that is the issue. The presence of Sanicle (below), for example, indicates that non-native Beech trees were introduced here (Sanicle typically grows under Beech trees).

While it can be hard to say in places where the original woods leave off and the new plantings begin, for the most part the interventions are fairly obvious. This creates a dilemma for those committed to restoring the woods. For example – the Killarney Fern is found here (below). Incredibly rare, it’s one of Ireland’s three types of filmy fern. Is it native to these woods or was it introduced by those fern-mad Victorians? Whichever it was, its presence here is what has conferred on these woods a Special Area of Conservation order. The fern requires shade, and that shade is currently being provided by invasive Laurel – see the problem?

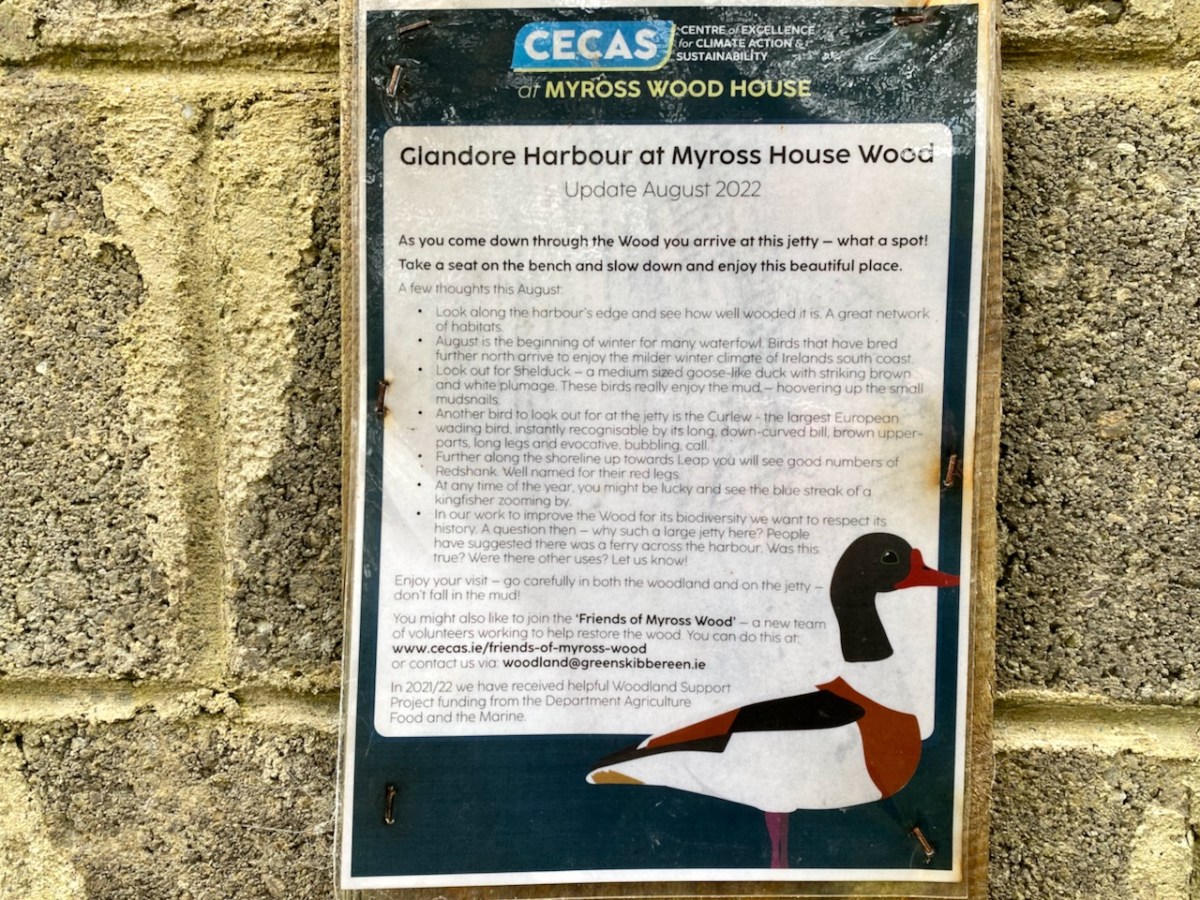

The Friends of Myross Woods has been set up to support the creation of a living, community woodland resource for biodiversity, education, recreation and the arts. They have been hard at work on a long-term project to restore the woods to something closer to a native woodland. They want to gently shift the site from a mixed broadleaf woodland to a more oak dominated birch and holly woodland (the most natural woodland type for this area).

On our walk Mark pointed out what has been accomplished and the immense amount that needs to be done. YOU CAN HELP! Sign up to become a Friend of Myross Woods, see what you can do to help, or make a donation to their efforts. Think how good you will feel, knowing you are doing your bit for this wonderful environment.

But even if you can’t do any of that, just go and take a walk in the woods – it’s open to everyone and it’s a restorative experience at any time of the year. There are two walks you’ll want to do, both short and easy. The first of the one to the south of the house, leading down to the water of Glandore Harbour. This is the walk we did yesterday.

The second is the Tunnel Wood walk, near the N71 entrance. It will bring you to the tunnel, dripping with bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) and on to the amazing bridge that Kingston had built to provide a suitably opulent entry to his demesne. Be careful here, though – it’s high and precarious.

Myross Woods is just one branch of the great work that is being done by CECAS (Centre of Excellent for Climate Action and Sustainability), an initiative of Green Skibbereen. By signing up to support CECAS you become part of a movement that is stepping up and actively tackling climate change in our West Cork Community.