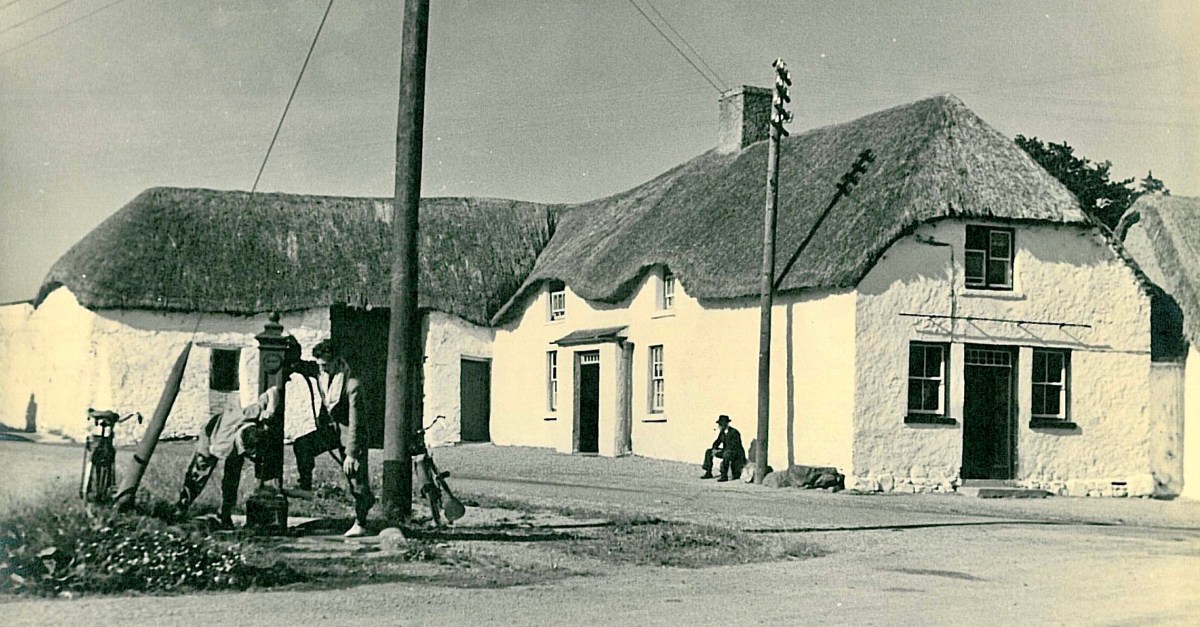

Above – on the left is the old Vaughan’s Hall in Ballydehob. Local historian Eugene McSweeney tells this tale:

. . . This hall in Ballydehob ‘had the Electricity’ around 1951-52. UK Queen Elizabeth II was crowned in 1953 – June 2 – and a film was made by the BBC. This film was sent around to be shown in village halls etc all over Britain, but also in Ireland. Vaughan’s Hall was able to borrow a projector, and an evening was set aside to show the coronation film. There were ‘some local lads’ who felt that good Irish citizens shouldn’t be gawking at this English Royal event. They brought some heavy chains, and threw them over the new electric wires connecting into the hall. This caused a short circuit and the lights – and the film – went out! Ballydehob had to wait for another day to see the coronation . . .

Eugene McSweeney, Ballydehob

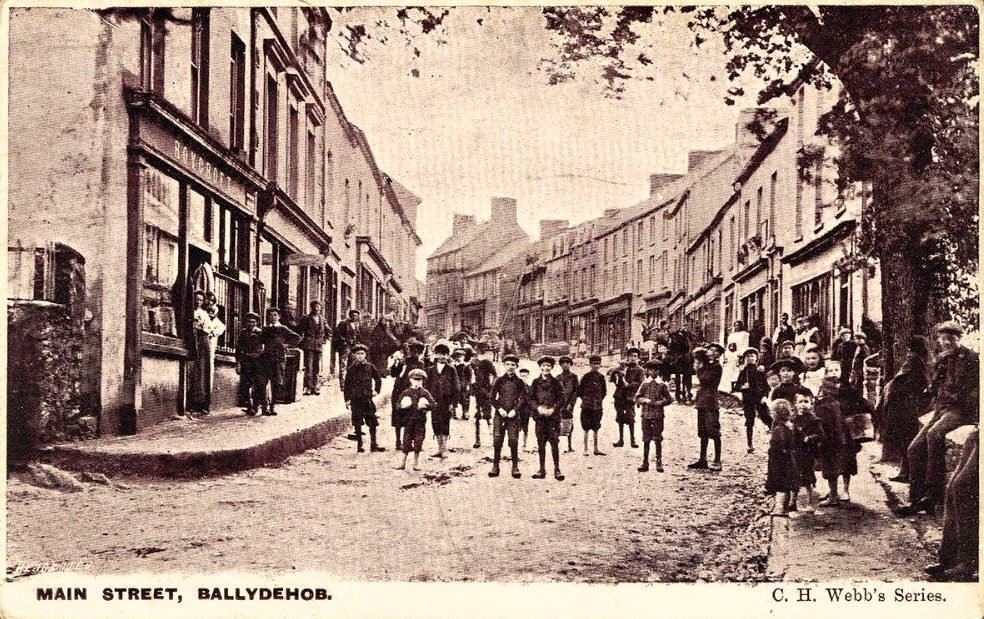

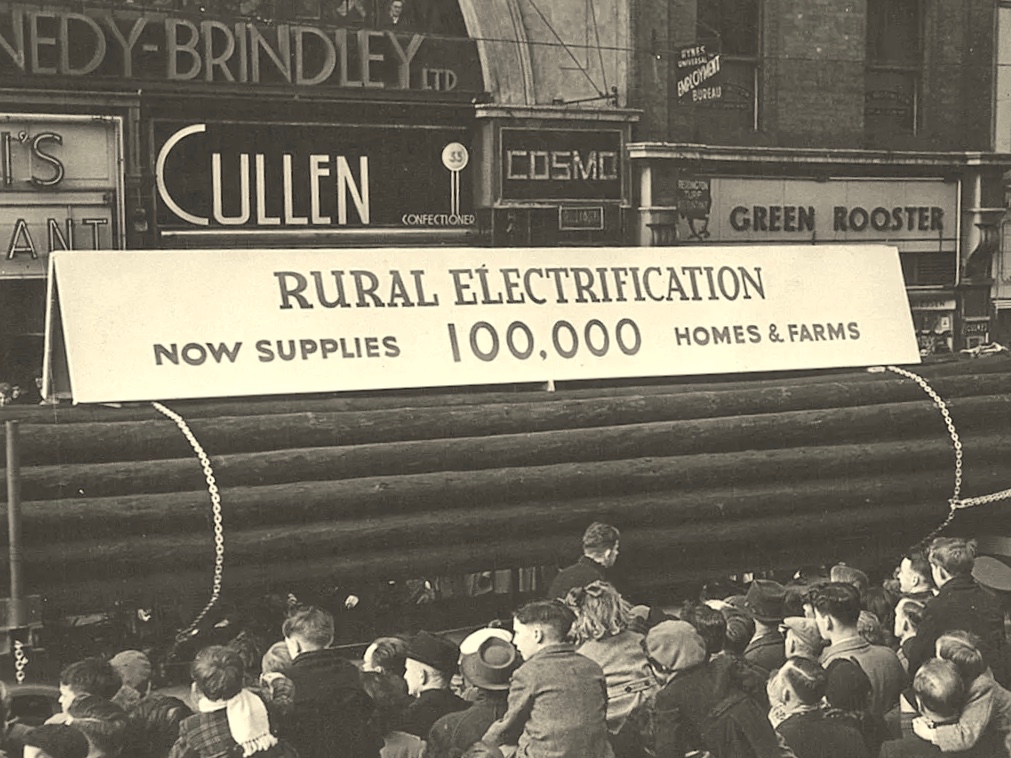

During the 1930s most towns in Ireland were connected to the National Grid. The outbreak of World War II in Europe led to shortages of fuel and materials and the electrification process in Ireland came to a virtual halt. In the early 1950s the Rural Electrification Scheme gradually brought electric power to the countryside, a process that was completed on the mainland in 1973 – not without some Herculean efforts by the on-site crews . . .

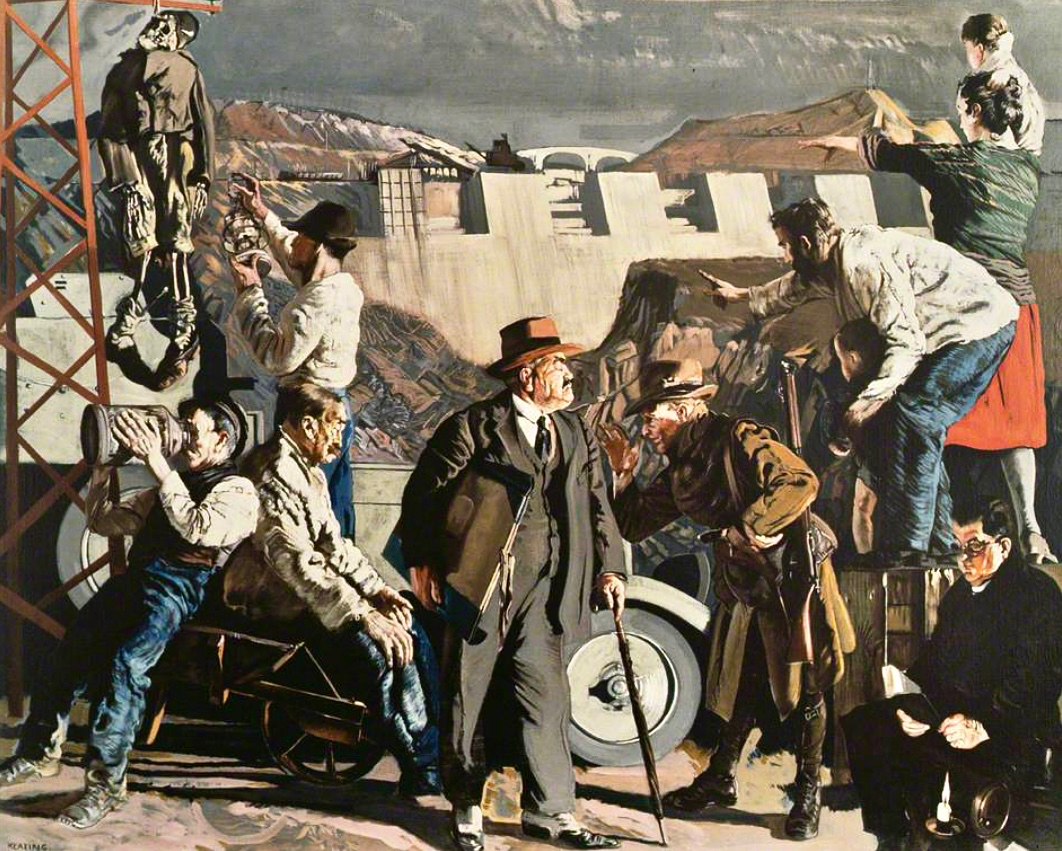

. . . While battling with the rocks in the Schull/Ballydehob fastnesses, blasting our way to our goal, we were informed that our next area was Castletownbere. No stick of exploding gelignite could produce more of a stunning effect in the Area Office than when the news reached us. Then we knew we were being accepted and acknowledged as mountainy men, men of steel and gelignite, capable of shaking still further the serenity of the West Cork mountains whose calm had not been disturbed by the noise of men and clash of steel since O’Sullivan Bere . . .

ESB ARCHIVES – AO Report 1951

Above – the pegging teams faced an onerous task when they moved over to the Beara Peninsula. Here are extracts from the reports of the Area Officer when works set out towards Castletownbere in late 1951:

. . . In November 1951 I left Ballydehob to visit Castletownbere area, the future scene of our endeavours. Looking at the country between Glengariff and Castletownbere I wrote off the battle of the Schull area as a skirmish, as I felt that the real battle was here. Here were crags, crevices, canyons, woods, bogs, etc, which defied all exaggeration. W Trusick, the pegging engineer, was very much depressed at the thought of what lay ahead of him as we climbed up the winding road from Glengarriff to the heights of Loughavaul and beyond again to Coolieragh. However, when we topped the climb at Coolieragh the vista of mountain and sea that met our eyes gave us a temporary respite from our morose reflections . . .

ESB ARCHIVES

Extract from the reports of the Area Officer when works set out towards Castletownbere in late 1951:

. . . Here was a scene that is hard to equal anywhere else in Ireland. Ahead of us lay the country of O’Sullivan Beara. Away in the distance lay Beara island like a sleeping monster resting on the sea, protected on the northern side by the massive bulk of Hungry Hill, and farther west by a ring of mountains whose western slopes dip down into the Atlantic Ocean. Behind us we looked across Bantry Bay at Bantry away in the distance sheltered by the bulk of Whiddy island. Nearer to us was Glengariff with its myriad of islets and heavily wooded hinterland, cosy and comfortable looking, secure in the shelter of its encircling mountains. On a cold November day in the weak wintry sunshine people do not stay long admiring scenery from such a dank vantage point as Coolieragh, and so we continued our journey westwards along by Adrigole, close to the Healy Pass, skirting the foot of Hungry Hill with its silver streak waterfalls and finally we arrived at the capital of the Beara Peninsula, Castletownbere . . .

ESB Archives

. . . Mr O’Driscoll and his crew in Dromahane, had apparently two major obstacles: First, the landed gentry who vehemently objected to the “beastly sticks” being put anywhere on their land: the second being a van which objected to moving under any circumstances whatever. Of the original 320 economic acceptances, 57 were ‘backsliders’, most of these being cottagers and small farmers. As an offset, 20 new consumers were gained, mostly having large premises, with the result that the total revenue was increased by £2. Only 20 premises were wired for outside light, due, in general, to the speed with which the contractors wanted to move from one house to another, and to their telling their clients that outside wiring could be done after they had been connected to the supply lines. Principal items sold in the area were 20 cookers, 30 irons, 20 kettles and 11 Milking Machines. Milking Machines are becoming increasingly popular in this area, solving as they do, the problem of milking on a Sunday when, normally, labour is not available. Mr O’Driscoll is doubtful if post development will meet with any marked success . . .

ESB Archives – DromAhane, Co Cork

It’s intriguing that the reports in the ESB Archives from the time of installation so often represent negative views about the ‘success’ or otherwise of the rural electrification project (Mr O’Driscoll is doubtful if post development will meet with any marked success). It’s as if this ‘new fangled’ technology is never going to take the place of the way traditional life is lived in remoter places. With this viewpoint, the drudgery of manual tasks such as bringing in water from an outside source, cooking, washing clothes is likely to continue, with the housewife / farmer’s wife and their children having maximum input. It’s just as well that a more enlightened attitude prevailed in some places – here’s an early taker of the benefits of an electric egg sorting machine (ESB Archives):

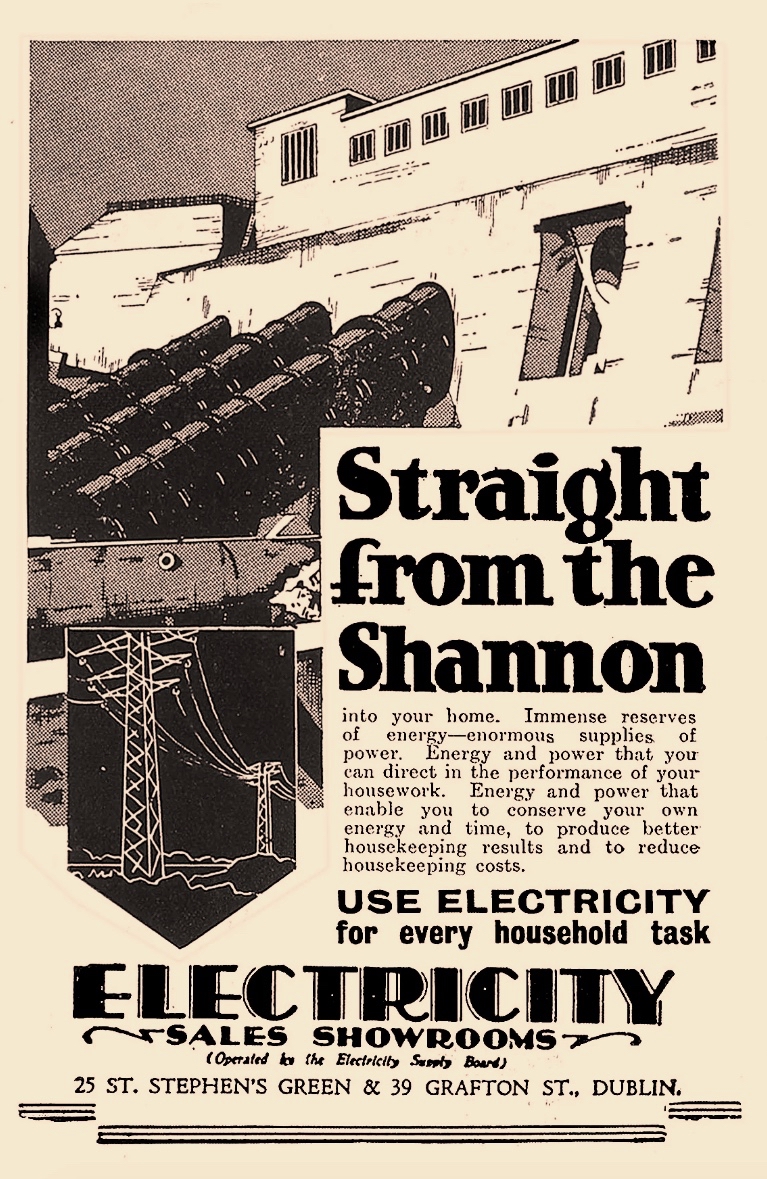

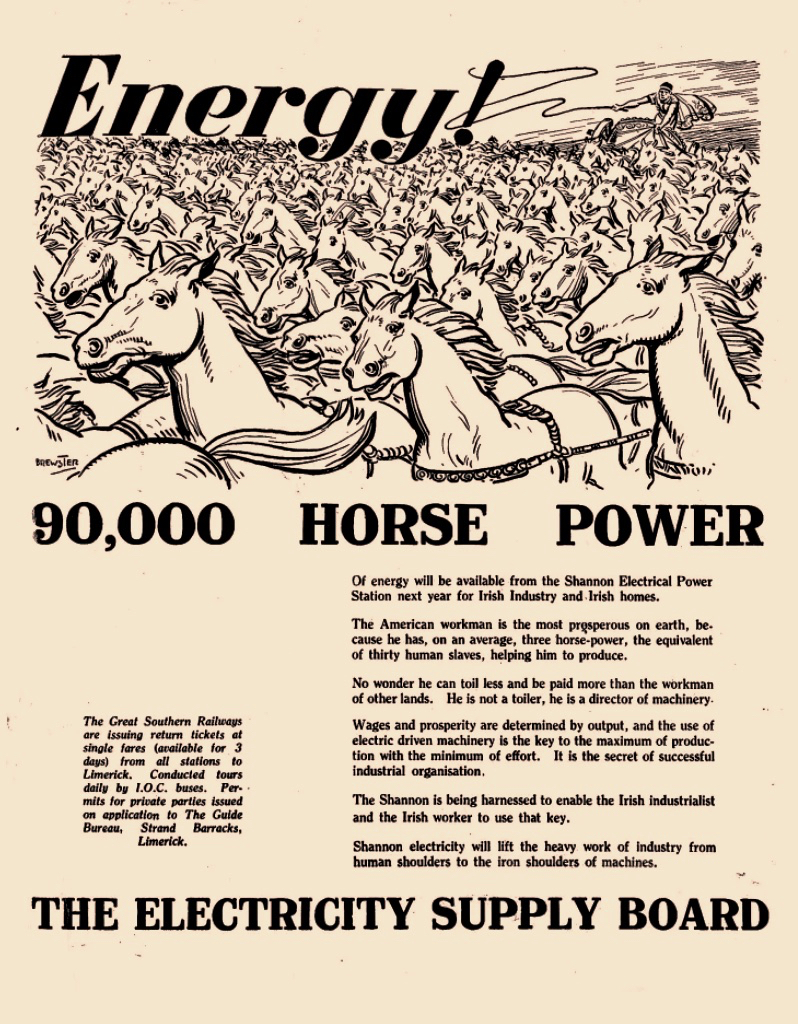

In urban areas, there was certainly enthusiasm for the improvements which ‘modern living’ offered (below). The new devices must have appeared exotic at first, but no doubt their benefits were instantly apparent to those who set their minds positively.

The heroes were the riggers and the geligniters, braving the elements and the raw landscape, to eventually bring power to the furthest reaches of rural Ireland (a task not completed, it could be said, until 1991, when Cape Clear – off our own West Cork coast – was connected to the National Grid). After those heroes came the dealers and traders. Someone had to provide all the water heaters, pumps, milking machines, refrigerators, cookers, washing machines . . . It was big business.

Above – an ESB salesman exercising persuasion on a willing customer. The man looks on! Below – interesting juxtaposition . . .

. . . Once a community was connected, or about to be connected, the ESB held public demonstrations of household appliances. These were then sold bringing electric irons, kettles, stoves to homes. The demonstration evening in Glenamaddy was held in January 1951. The handwritten report records that it took place “in the very fine Esker Ballroom”; these events were social occasions that brought communities together. The Glenamaddy evening “was attended by about 90, including 50 women. As is usual, the women appeared to be more keen than the men and more inclined to ask questions (and to argue). After the demonstration, a melodeon player turned up and an impromptu dance got under way” . . . Small towns and rural townlands became brighter and winters less harsh and Christmas more special as the fairy lights began to shine. It also gave rise to a rural Irish icon as every house had the Sacred Heart picture with the (electric) red lamp: many didn’t get a kettle and washing machine until later on . . .

ESB ARCHIVES

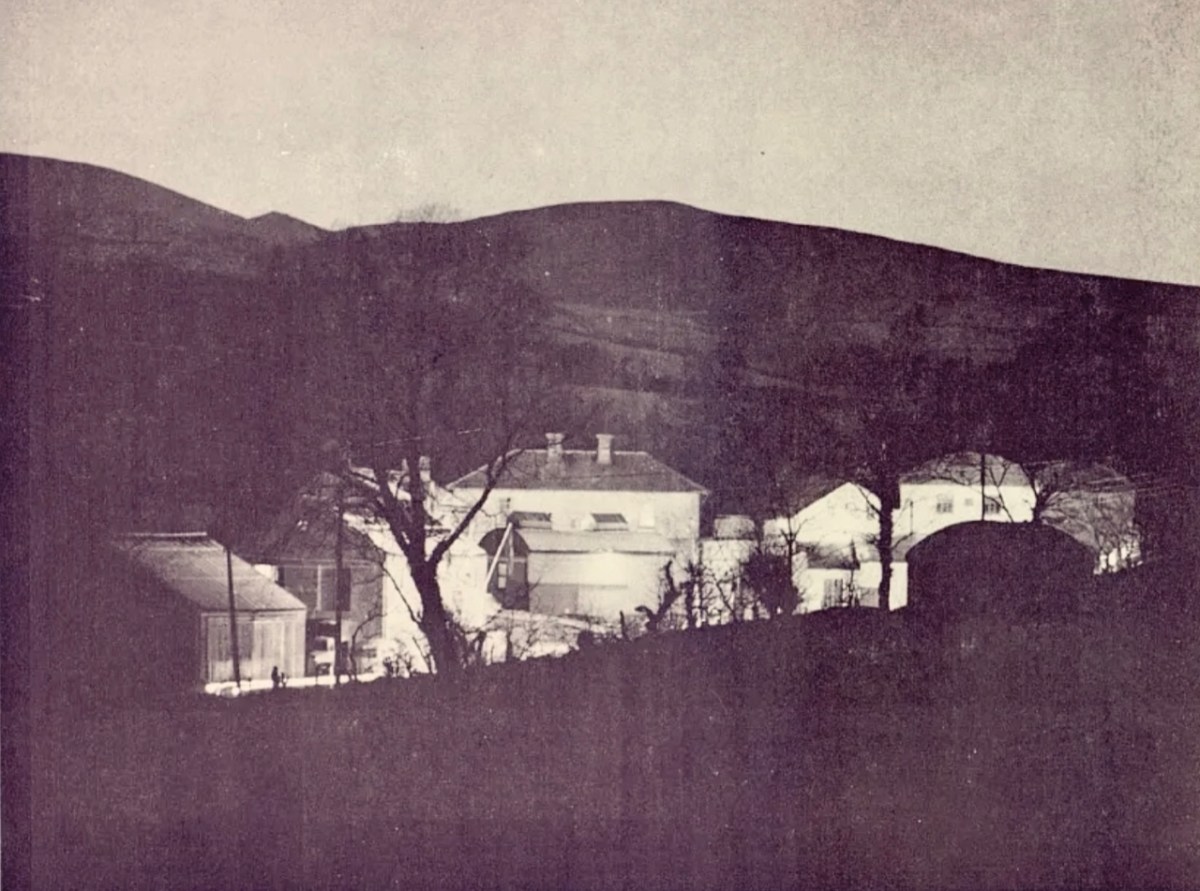

(Above) Seán Lemass – Minister for Industry and Commerce – performing the formal ‘switch-on’ in Ballinamult Creamery (Co Waterford) on 1st March 1954. This was the Electricity Supply Board’s 100,000th customer. Also in attendance are Mr R F Browne, ESB Chairman, and The Very Rev Father Walsh, PP Ballinamult.

Above: “As the last rays of sun leave the hills, the lights go on at Ballinamult Creamery, the Board’s 100,000th Rural Consumer”

. . . In November, Miss Crowley of the ICA toured Sherkin Island and lectured in nearby Skibbereen giving her ideas on modern home-making and sponsoring the use of electricity to a great extent. The area demonstration at the end of November was very well attended and sparked off a keen interest in the various appliances on show, just as the connections in the area were commencing. ESB sales in the area are now in the region of £1,300 while contracts are on hands for six pumping installations . . .

ESB ARCHIVES

Thanks once more to Michael Barry for inspiring this brief study. Also to the ESB Archives, The Irish Story and Eugene McSweeney. Roaringwater Journal is always pleased to receive comments and contributions on any subject we take up.

Previous posts on Ireland’s Electrification: