If you are travelling through County Limerick, you shouldn’t miss a visit to Ireland’s largest stone circle: Grange, near the Lough Gur complex. There are 113 stones in this circle today, generally standing close by each other (‘contiguous’) and thus unlike the majority of the circle monuments in Ireland, where individual stones are separated.

The great circular arena which these stones define is also on a platform raised (in the present day) about 600mm above the surrounding land. Excavations which took place between 1939 and 1954 (S P Ó Ríordáin 1951) and subsequent radiocarbon dating indicate a construction date just short of 3,000 BC, which makes the circle one of the oldest in Ireland.

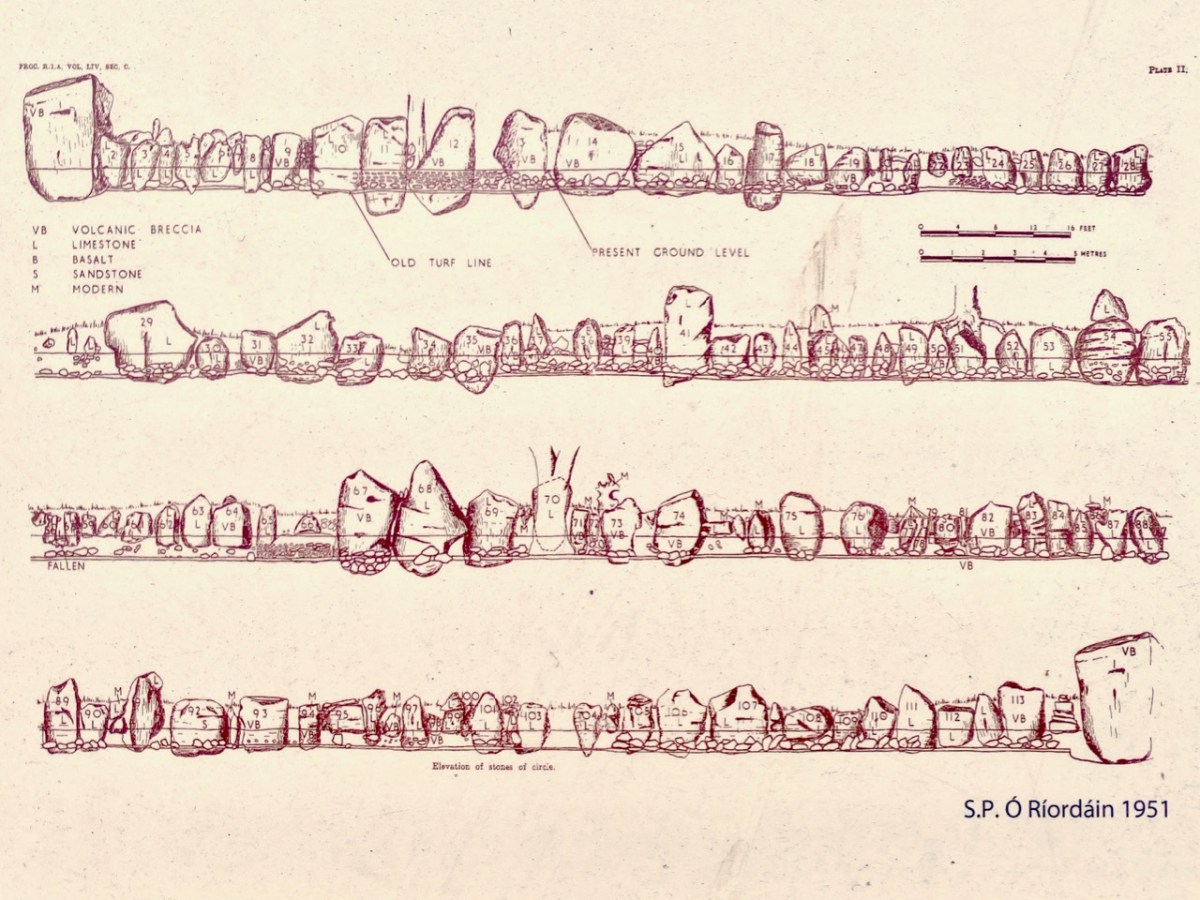

The internal diameter of this circle (a ring drawn around the inner faces of the stones) measures approximately 45.5 metres. Here is Ó Ríordáin’s drawings of the elevations of the stones:

Finola bravely stands against the largest stone in the circle, which is traditionally named Rannach Crom Dubh. The meaning is not clear; Crom suggests ‘bent, crooked, or stooped’, while Dubh means ‘black or dark one’. Rannach can mean ‘open-handed’, which could imply a trading connection. This stone is said to weigh over 40 tonnes and was brought to this spot from three kilometres away. Interestingly, some say that this stone marks the ceremonial entrance into the circle and is aligned with the sunrise on the 1st of August, known as Lughnasadh, the day that marks the beginning of the harvest in Ireland. In fact, there are many orientations that can be given to this circle. This article by Ken Williams explores some possibilities here.

This Beaker pottery sherd was found and recorded by Ó Ríordáin. It is one of a great number of such remains to be found at the site. One commentator made the suggestion that . . . The breaking of Beaker pots against the standing stones seems to have been part of a ceremony . . . Can we trace the more modern tradition of breaking wine glasses after a toast to such an early origin? It’s said to bring luck and happiness in some cultures. This would, of course, imply that the great circle was a celebratory feasting site.

There is evidence today that visitors feel compelled to leave offerings at the site: coins, small stones, beads, and other ephemera. The examples above are adjacent to Rannach Crom Dubh, while below is one of the standing stones in the circle that appears to have been deliberately cut, or slotted, at some time in its history. Today, coins are deposited within this slot.

My own feeling about this site is that it is an arena where people gathered to feast and celebrate. An ancient ‘circus’ perhaps? Ken Williams analyses the possibilities of archeo-astronomical alignments in his article, mentioning our West Cork friend Vice-Admiral Boyle Somerville, whose detailed work we have investigated, here.

The features of this site are fascinating and provide much food for thought, especially when seen through the eyes of archaeologists. Of course, we want to know who conceived this monument, and who was in charge of the human power and organisation that was required to erect it. There won’t be a simple answer to this: it’s likely that many generations were responsible and that there were numerous incarnations over time. That’s what is so fascinating about ancient history: if only we had a time machine!

There are traces of other, smaller, stone circles close by this one, but I was intrigued to read in one of the accounts of this site that there was previously a further – even larger – circle nearby, and this has vanished altogether. I have to ask: how could such a massive structure disappear completely? Legend gives us an answer: it was supposedly stolen by Merlin and brought over to England to create Stonehenge!