Harry did several wonderful St Brigid windows, and included Brigid as a saint in larger scenes. There are also Brigid windows attributed to him that he actually didn’t do, but that’s a blog for another time. Today I want to give you a flavour of his take on Brigid, because this was a saint that must have been especially meaningful to him – his mother was a Brigid!

Brigid (sometimes given as Bridget) MacGonigal was born in Sligo and married Joshua Clarke, then an up-and-coming church decorator in Dublin and they had four children. Harry, their third child arrived in 1889. Brigid was never strong and died in Bray in August 1903, leaving her family bereft. Harry was 14 and that year marked the end of his schooling at Belvedere as he and his older brother Walter joined the family business to help run it. Harry was a sensitive child and it is likely that he missed and mourned his mother for many years. He also inherited her weak lungs and struggled, as she did, with his health.

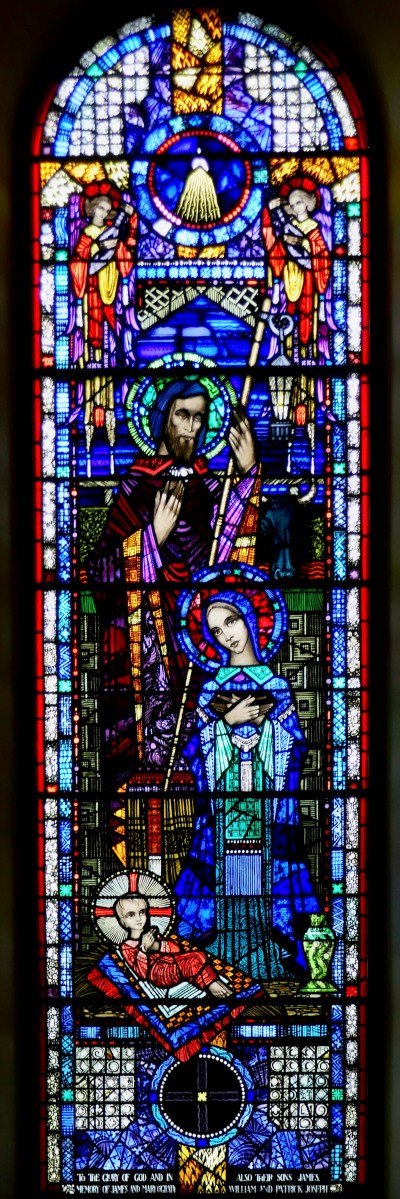

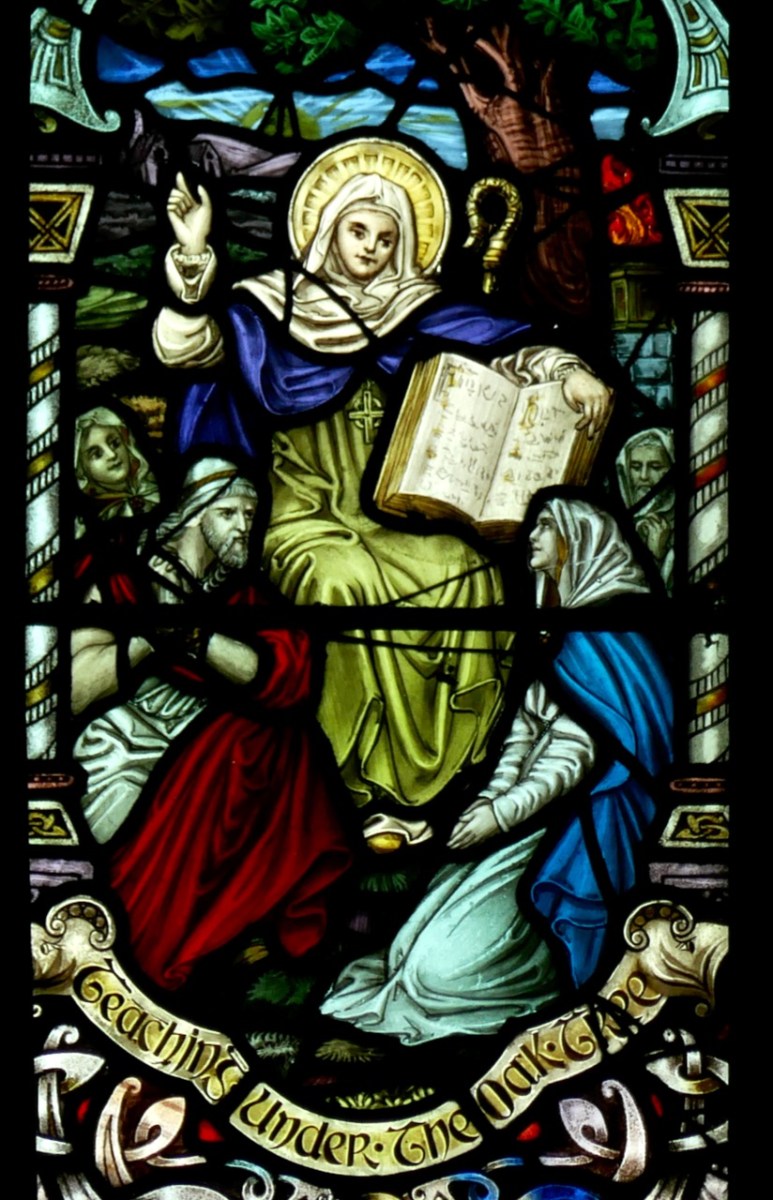

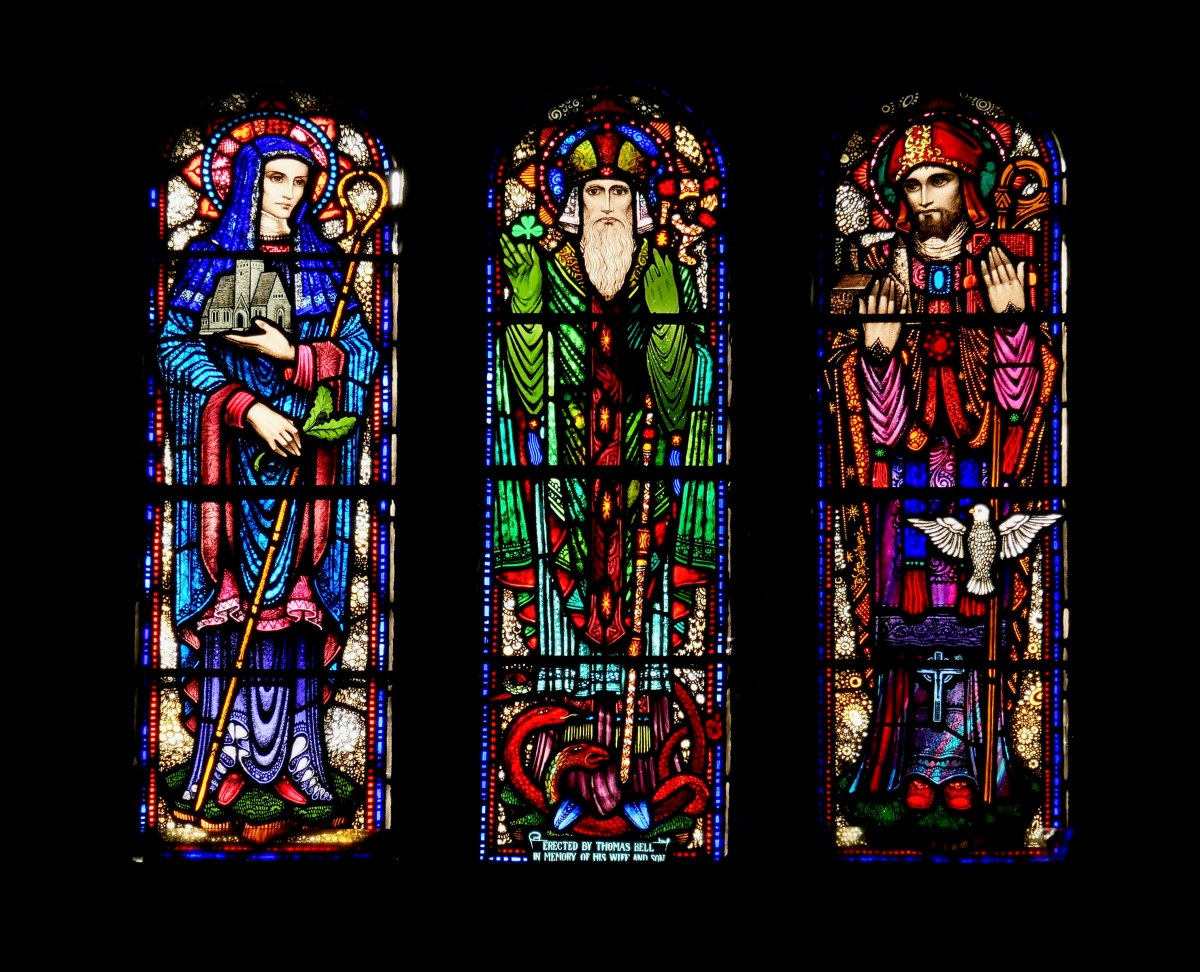

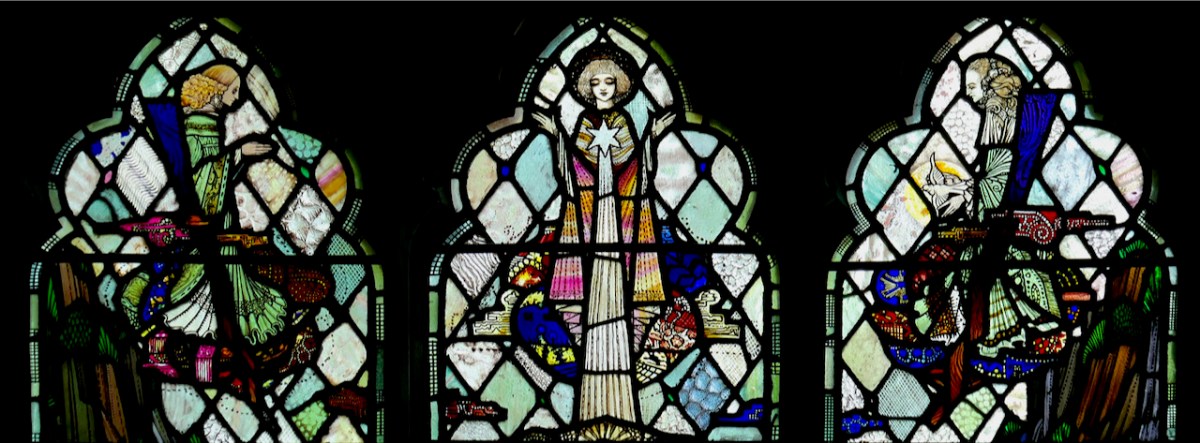

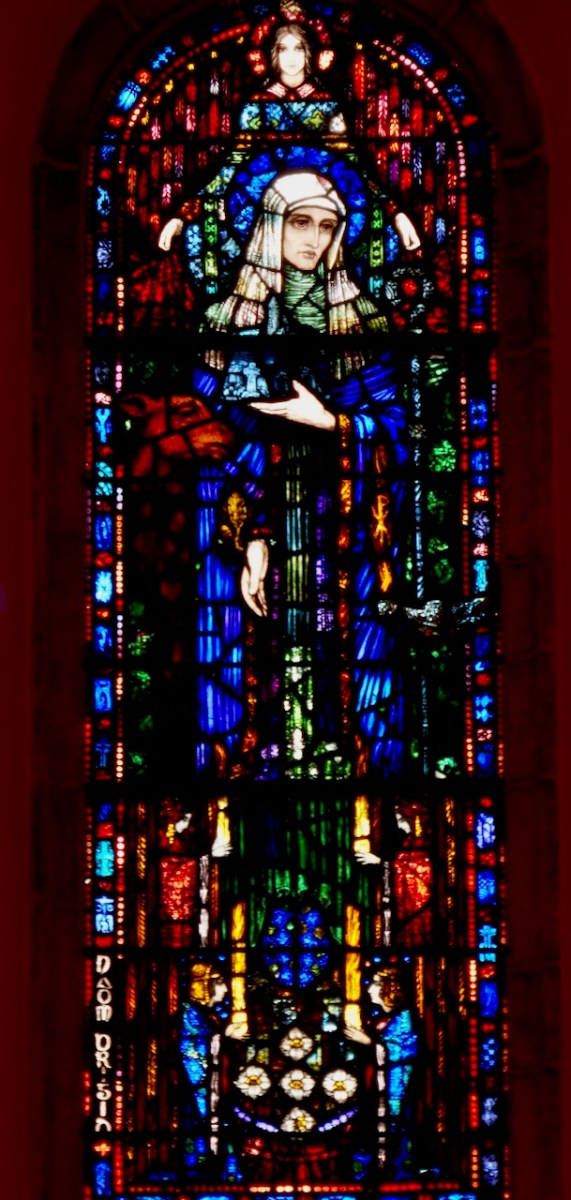

I will start with the place that launched Harry’s career, the Honan Chapel at University College Cork (I’ll finish with the one that is on my lead photo). And in fact it is his first windows for that Chapel – a three light, depicting Brigid, Patrick and Columcille, our three Patron Saints. This window is over the entrance, facing west, which, with Harry’s preference for dark colours and some internal lighting issues in the chapel, makes it hard to photograph.

Harry had completed a detailed sketch design for this window in 1914 (Nicole Gordon Bowe has an image of that design in her magnificent The Life and Work of Harry Clarke) and the window was made in 1915. There are a few differences between the sketch design and the finished window, but on the whole, the window is true to Harry’s original vision for it. His notes for the window refer to

Top: The Angel with the cloth of heaven forming background

The Figure: With emblems – the church, the inextinguishable spiritual lamp – the calf and the oak.

The Base: Are four angels carrying the prayers, prophesies, miracles and charities of St Brigid, also are shown the five lilies – she has been called the Mary of Ireland and these lilies symbolise the five provinces of Ireland over which she held spiritual control.

The cloth of heaven has been imagined as fronds in deeps reds, while St Brigid is shown as mature, wise and compassionate. She is holding a church which looks a lot like St Kevin’s Kitchen in Glendalough. In her other hand is a brown oak leaf, threaded through her fingers. The calf peers out from her right side. As befits a Mary of the Gael, she wears a deep blue robe.

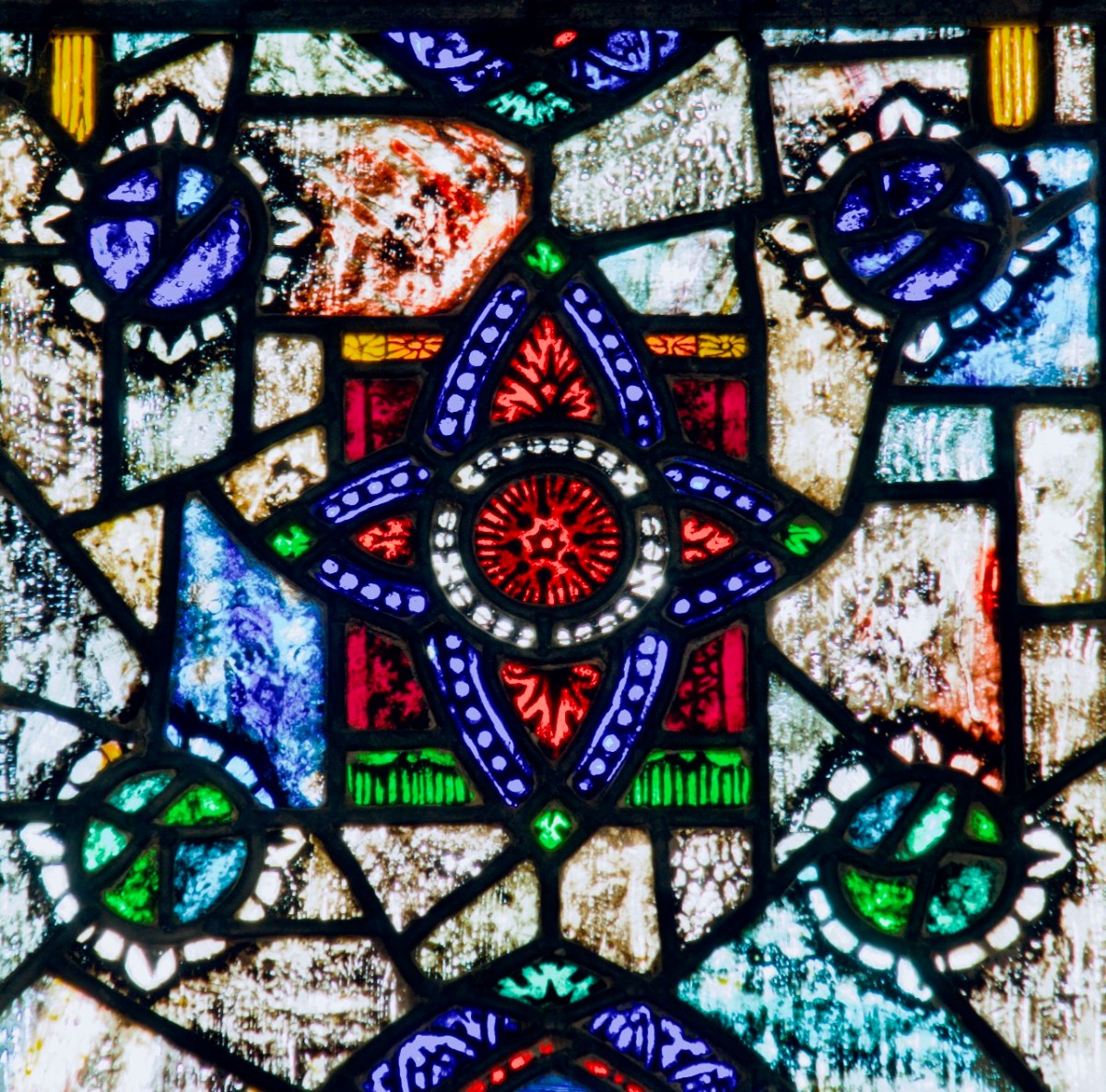

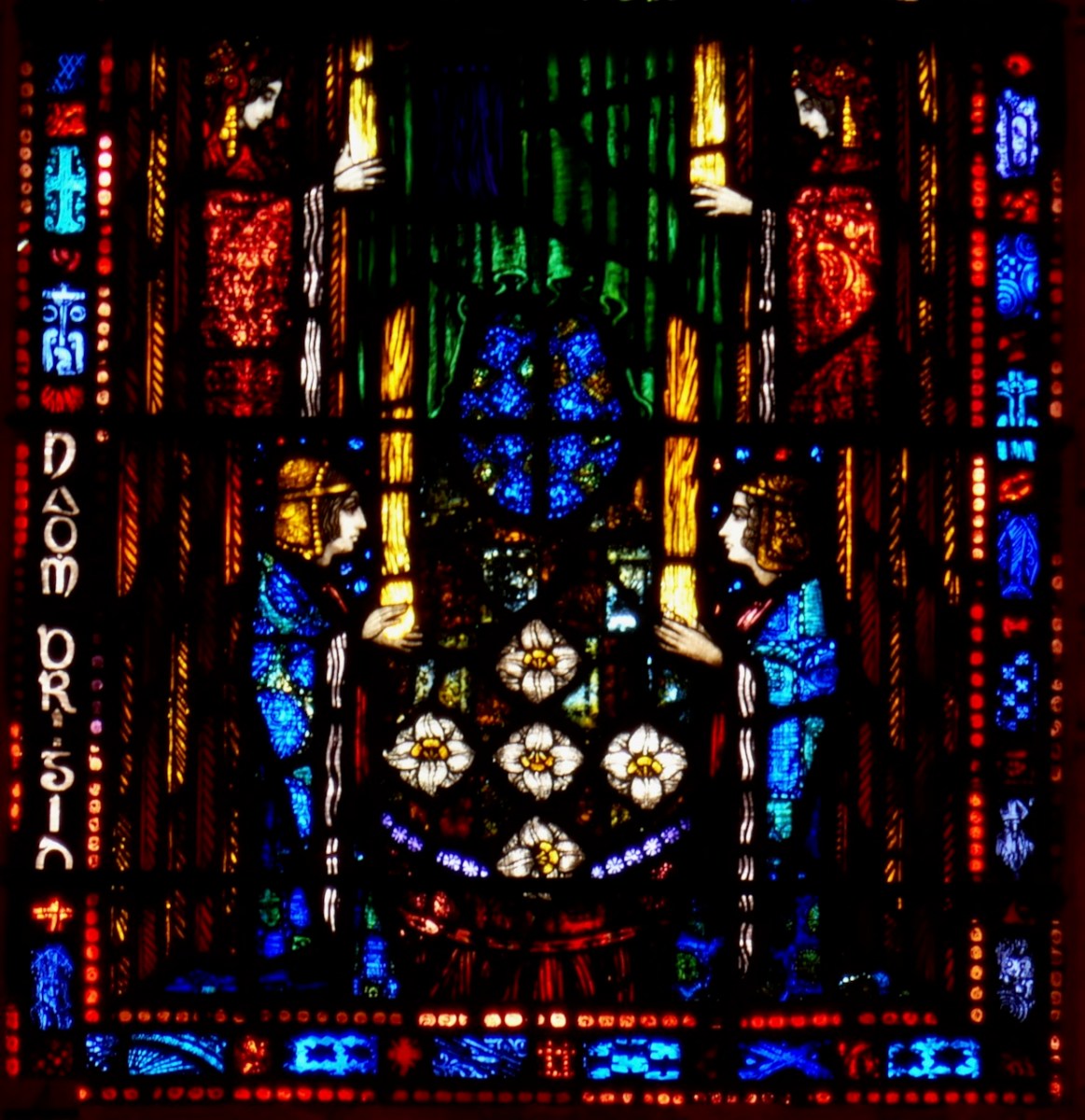

The predella (lowest section, above) shows four angels, but what they are carrying are torches – a reference to the spiritual lamp and the fire associated with Brigid. The symbols of the five provinces, recognisably lilies in the sketch design, have changed to another flower I can’t name. Note the tiny details, though – the crucifixion scene in the borders on the left and the right. The other detail to note here is that the fingers, of Brigid and the angels are ‘normal’ – Harry has not yet developed his signature long tapering fingers and pointed sleeves (among the idiosyncratic elements he called his “gadgets’).

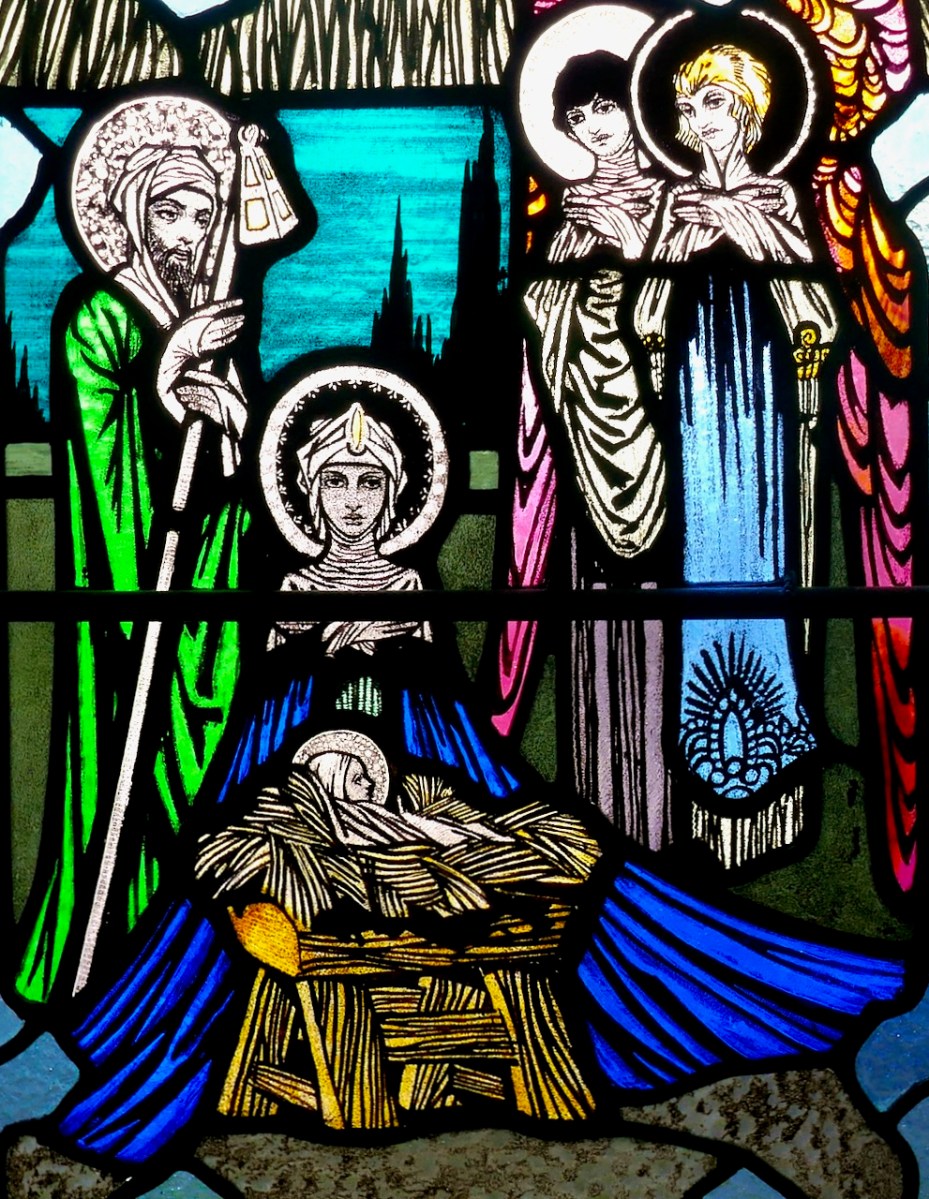

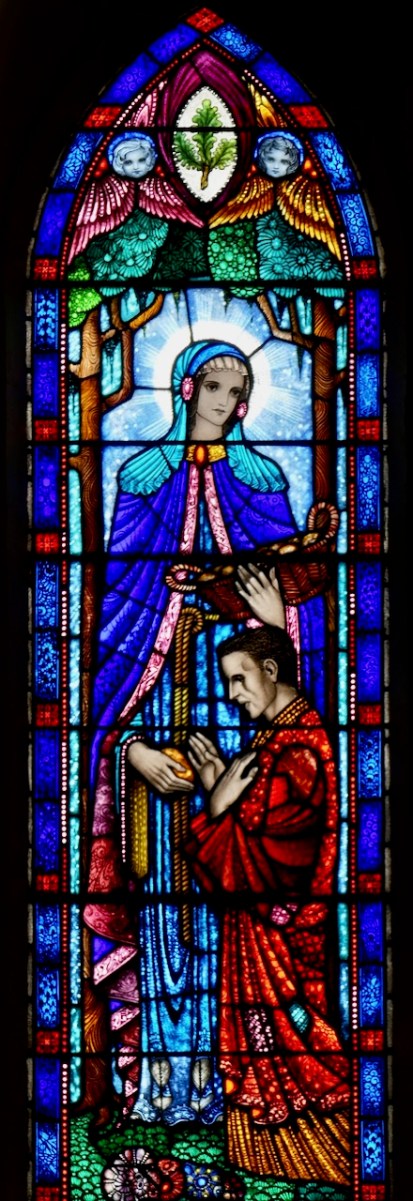

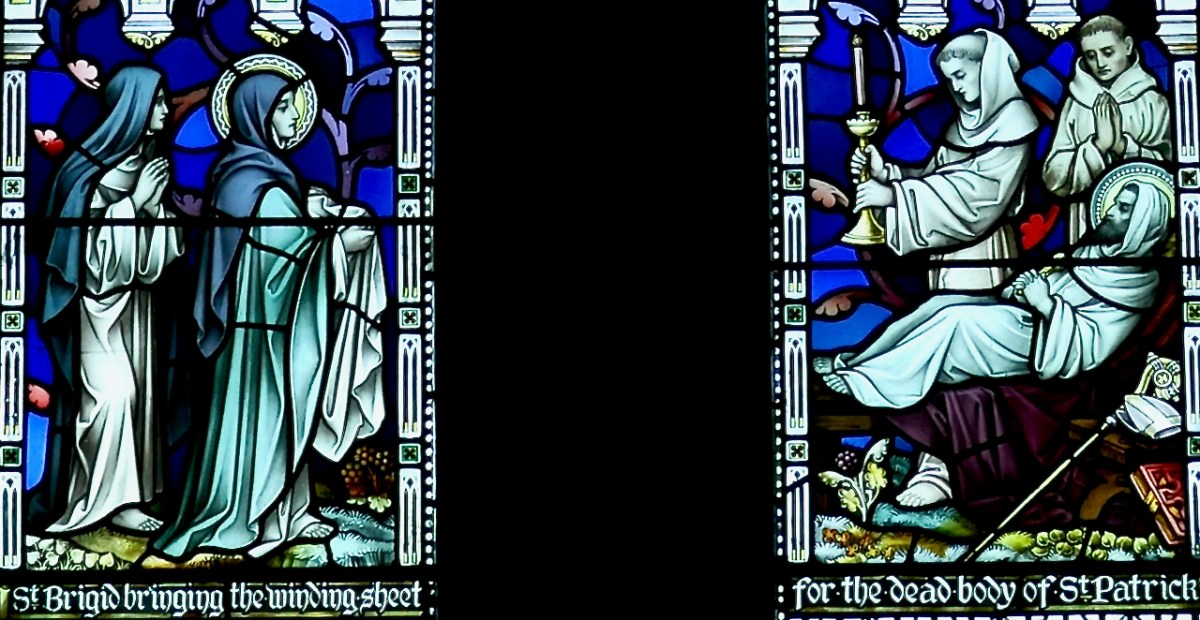

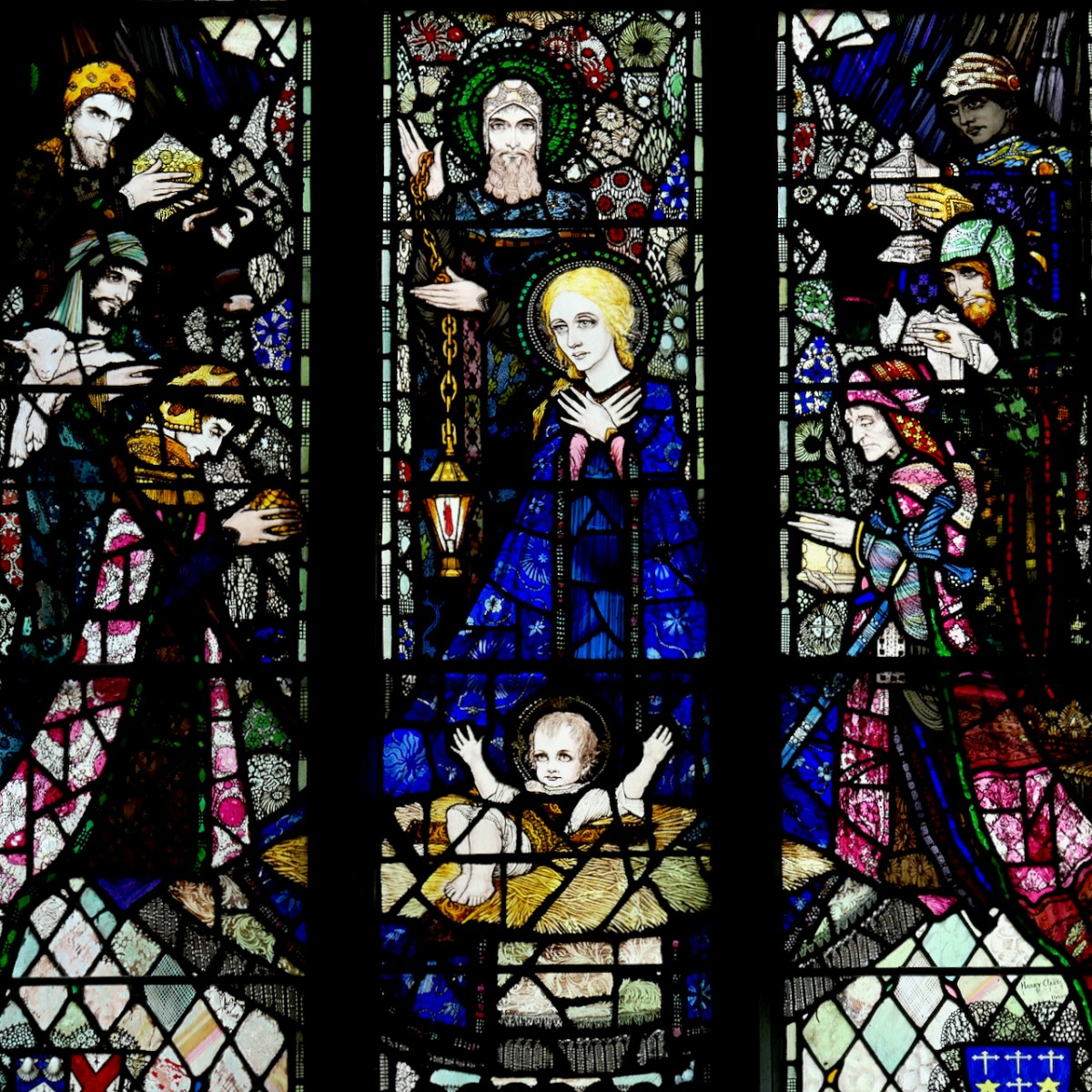

His next Brigid (above) was for the Nativity window in Castletownsend – I have written about that window extensively here so pop over and have a browse if you fancy. The Castletownsend Brigid, done in 1918, looks quite similar to the Honan Brigid and has the same oak leaf entwined in her fingers. The difference is that she is carrying the sacred lamp, has the Harry Clarke fingers, and is spelled S Bridget – the English version rather than the Irish Naomh Brighid of the Honan. [For non-Irish speaking readers – the small dot on top of consonants in Irish is now normally rendered as H – as in Briġid is now Brighid.]

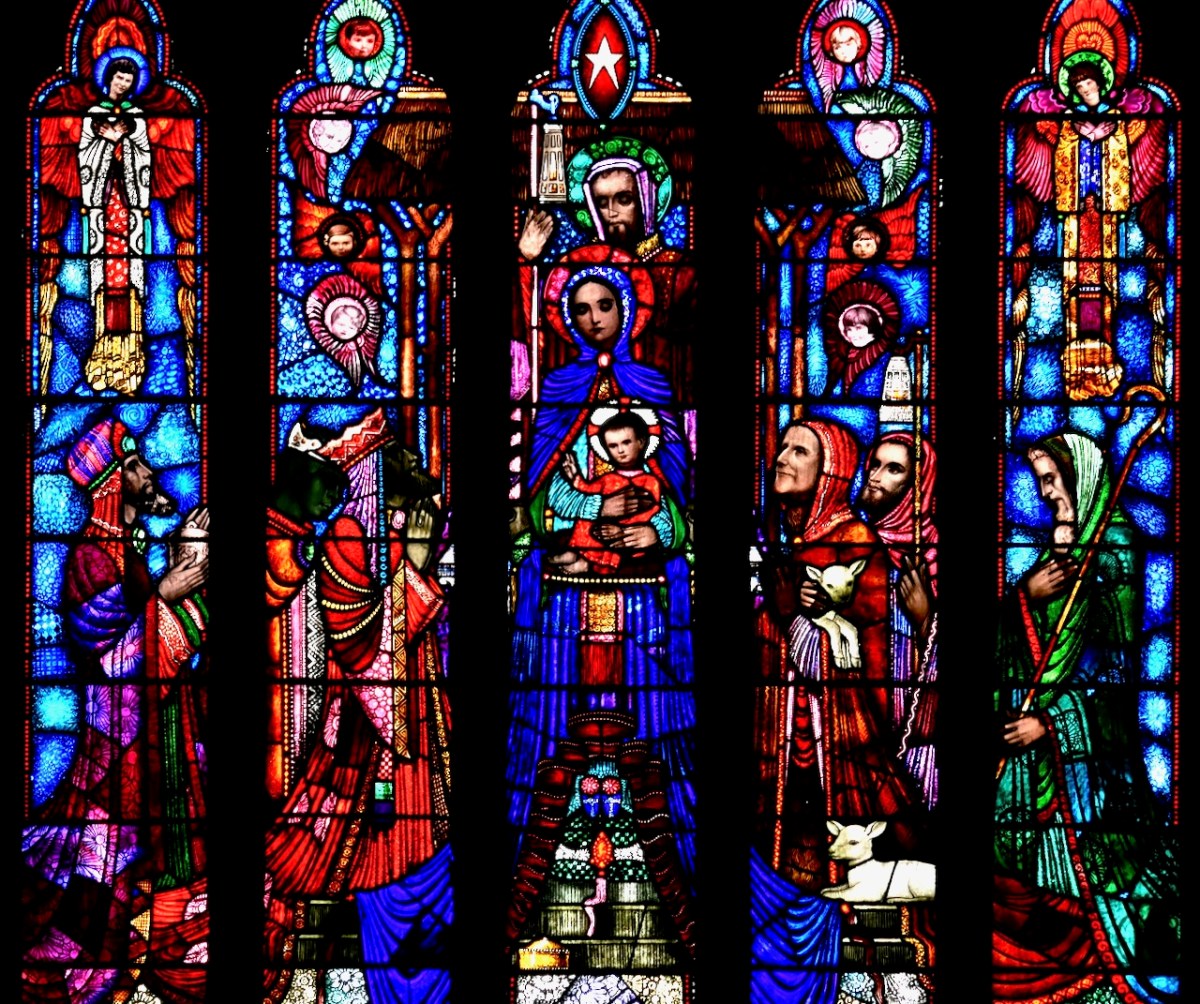

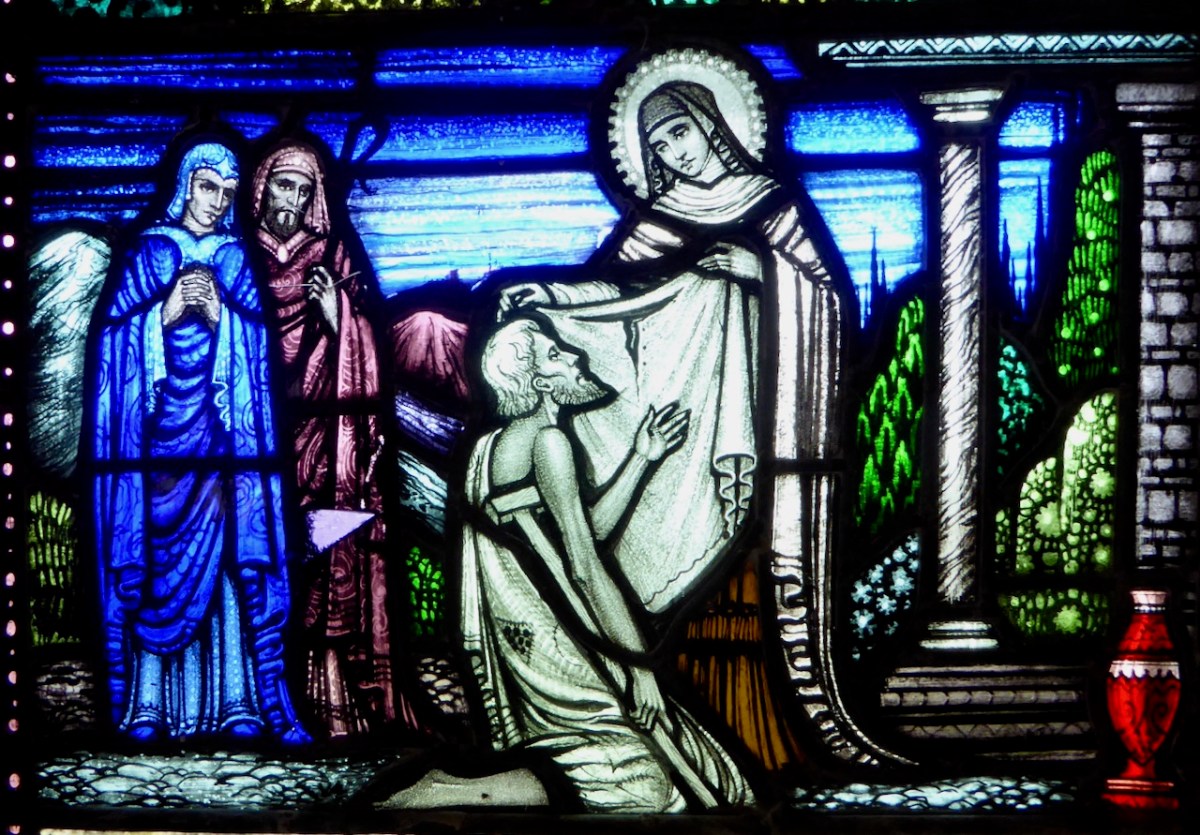

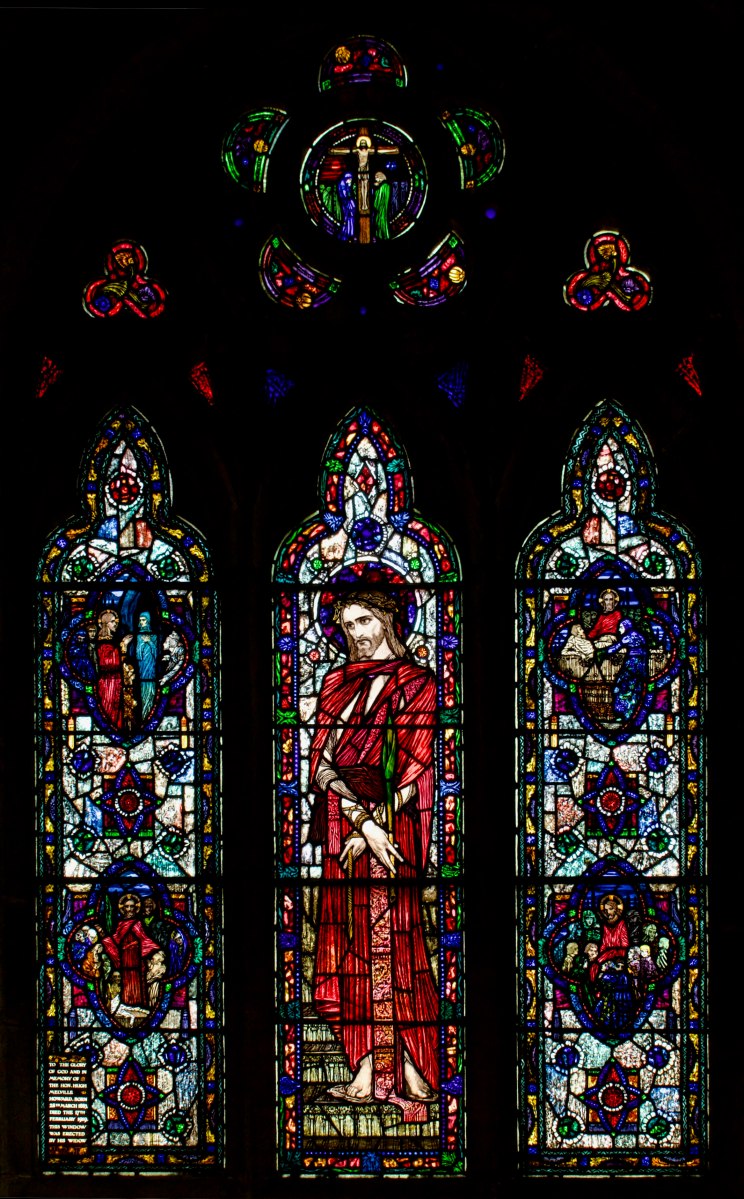

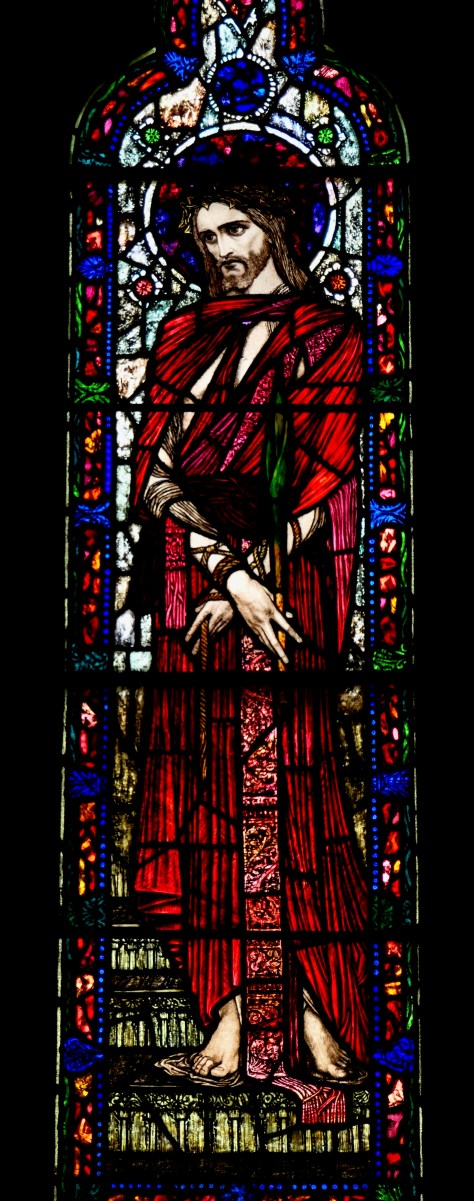

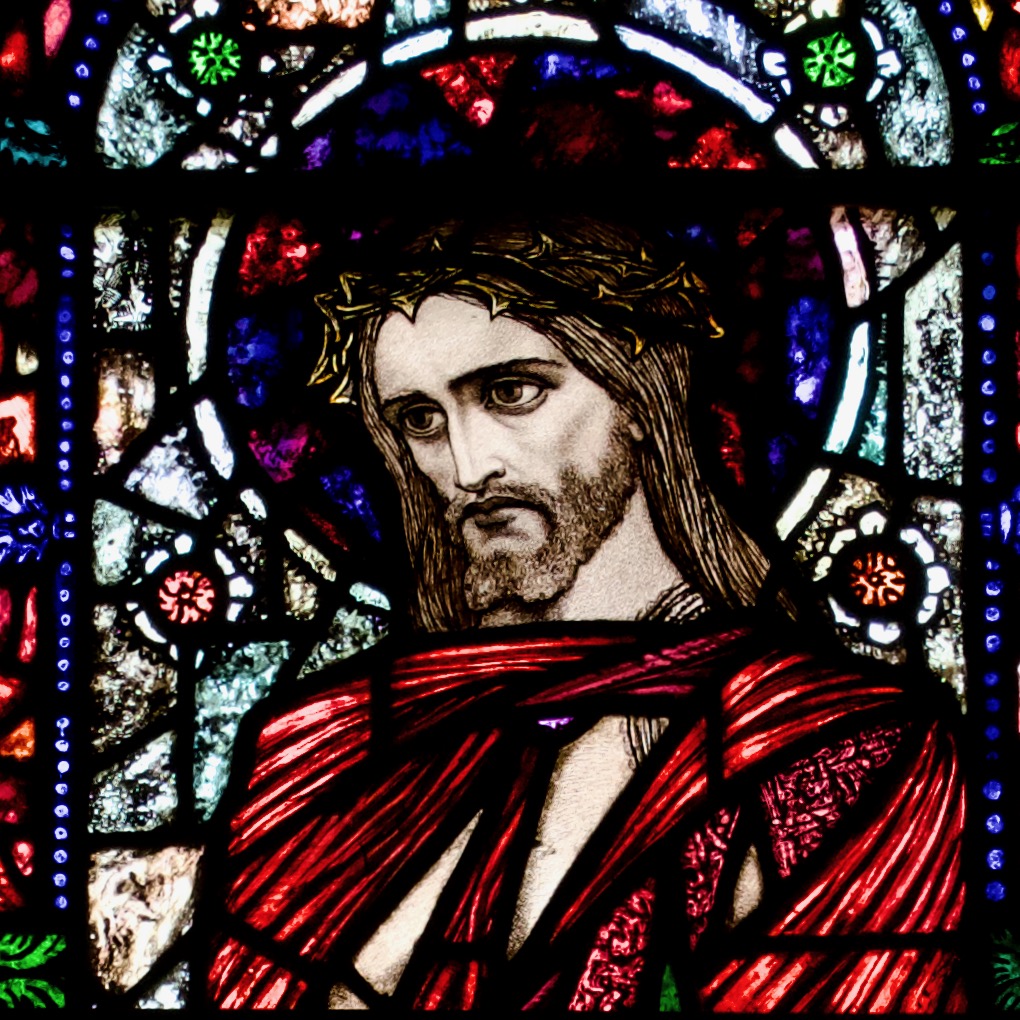

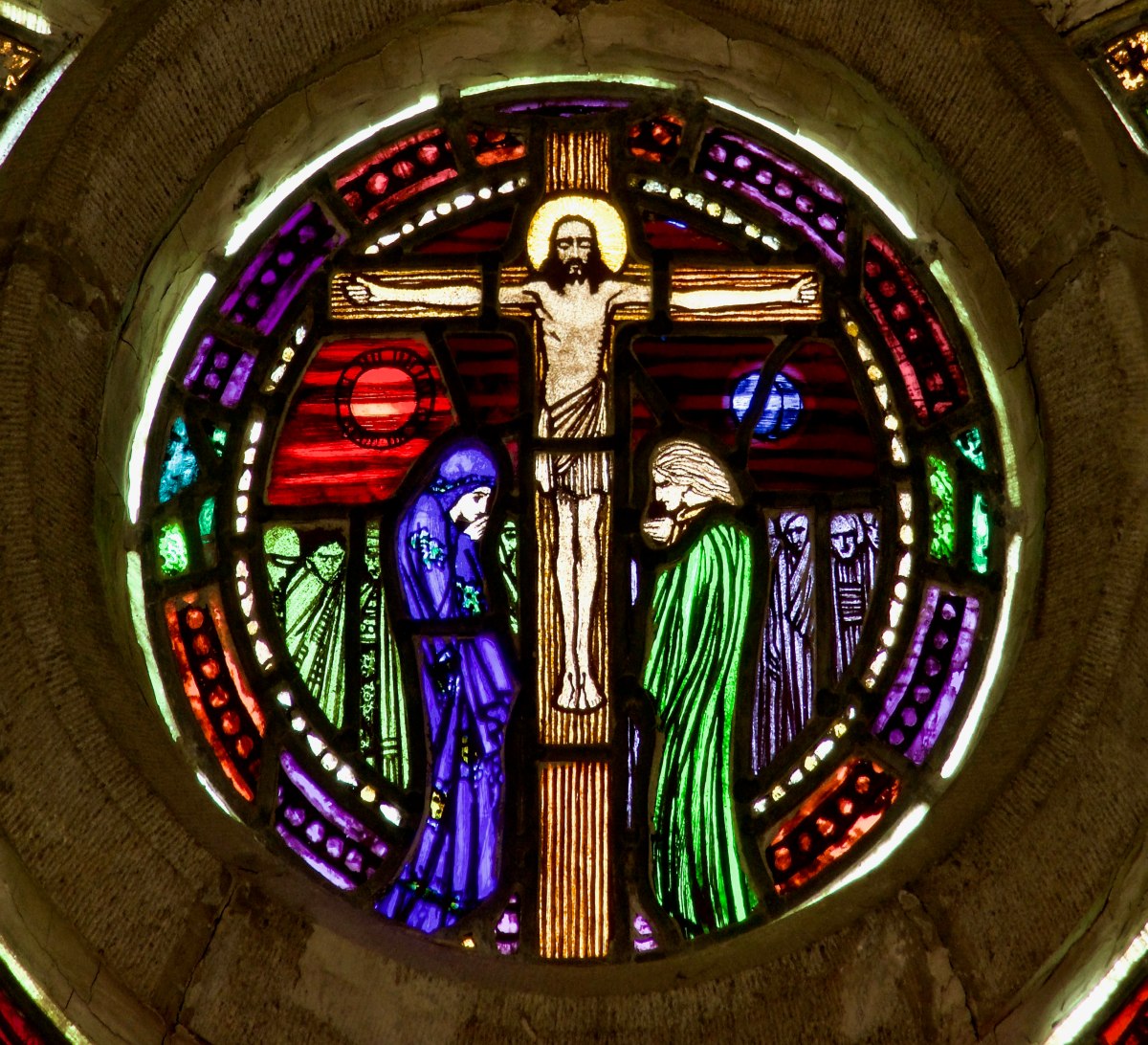

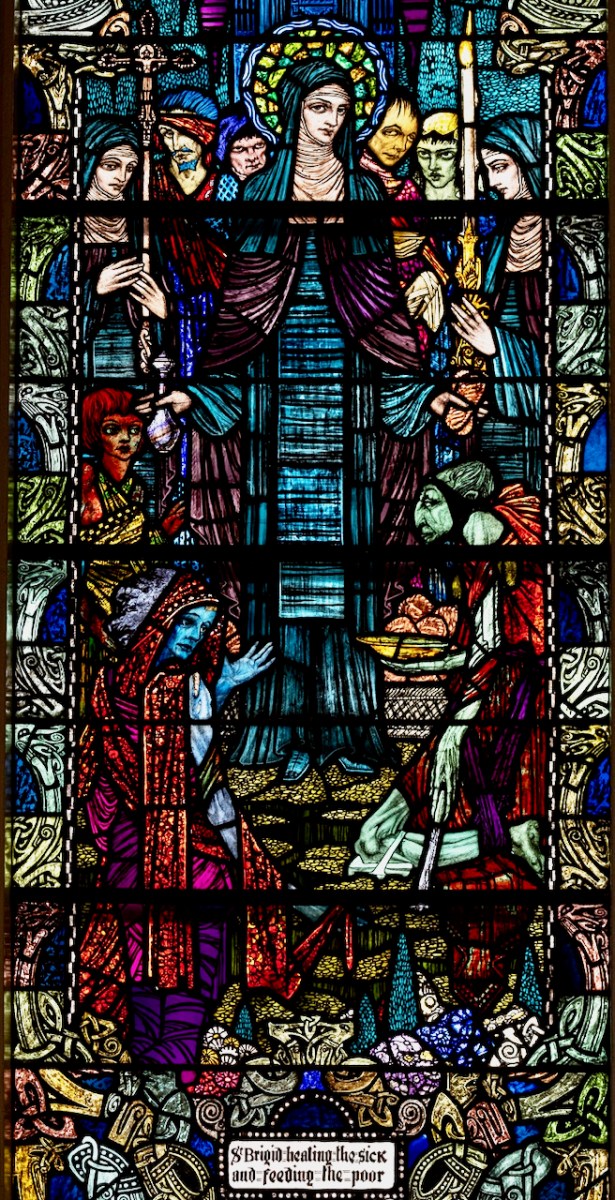

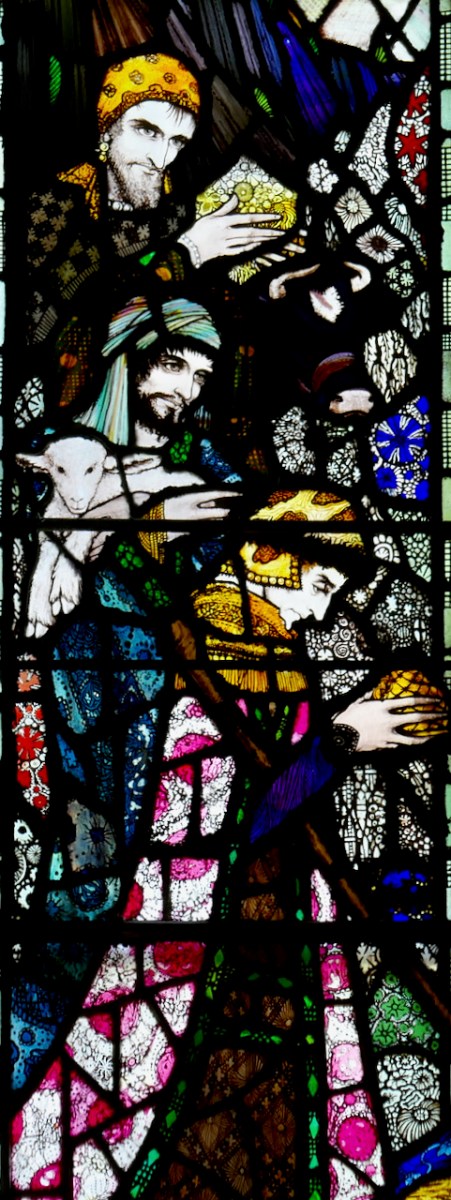

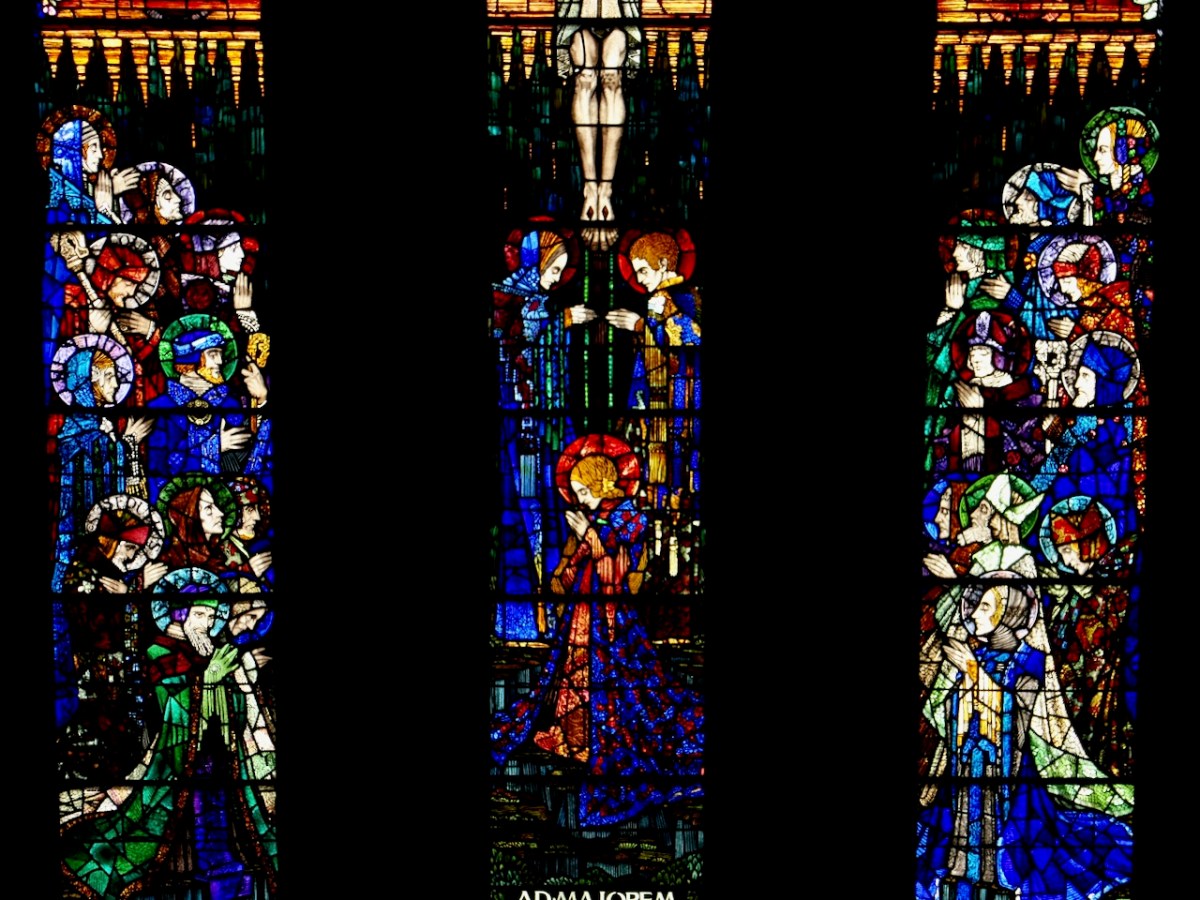

The next two windows, Terenure (above and below, details) from 1920 and Cloughjordan from 1924, show Brigid among a host of other saints. In Terenure the subject of the large window is The Crucifixion and the Adoration of the Cross by Irish Saints, and this is a large, three-light window behind the main altar. The saints are not all easy to identify, despite having their names in their haloes, but first and foremost among them are Patrick on the left and Brigid on the right.

Brigid is dressed in a blue robe which drapes on the ground around her, and has a golden trim to her sleeves.

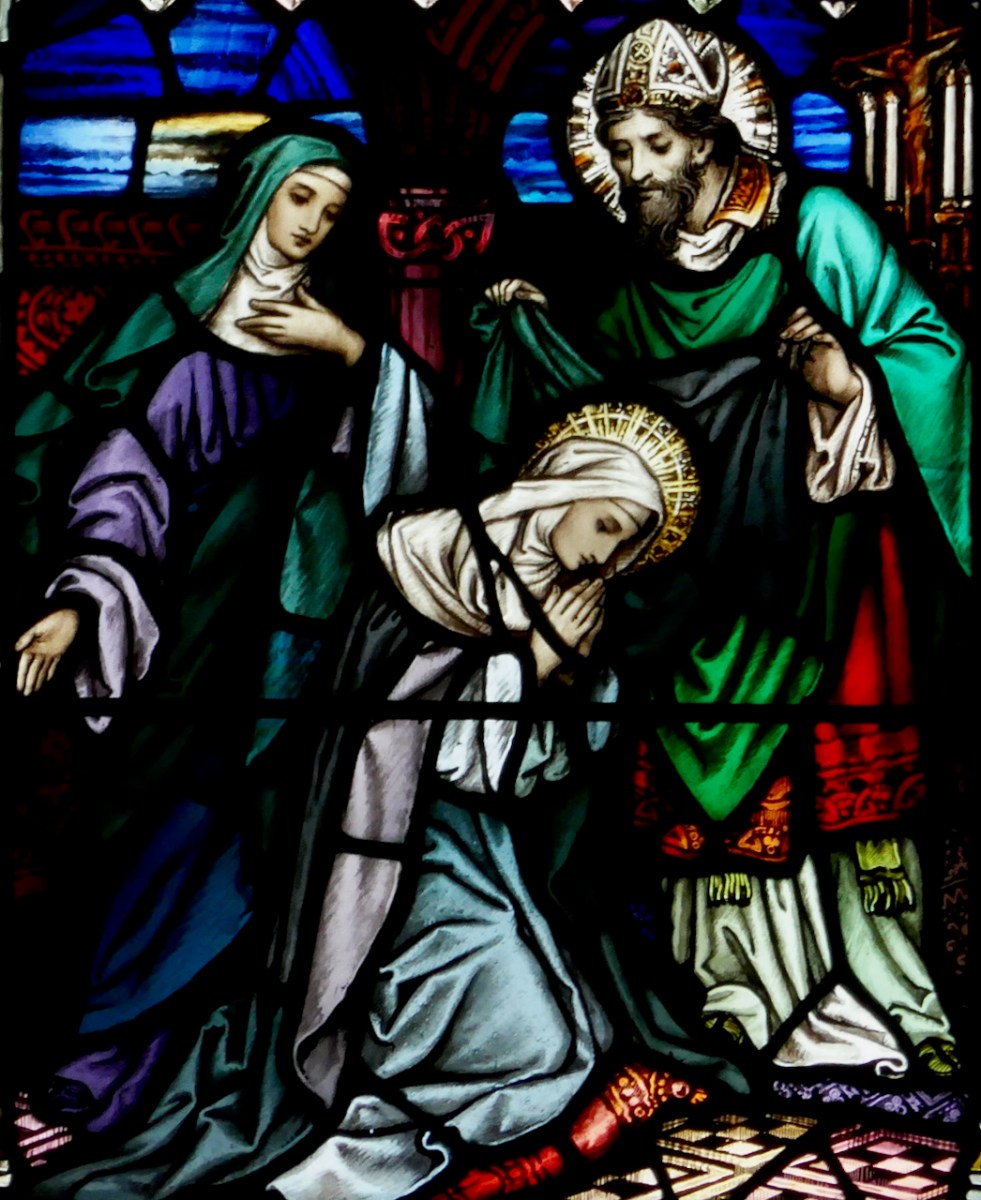

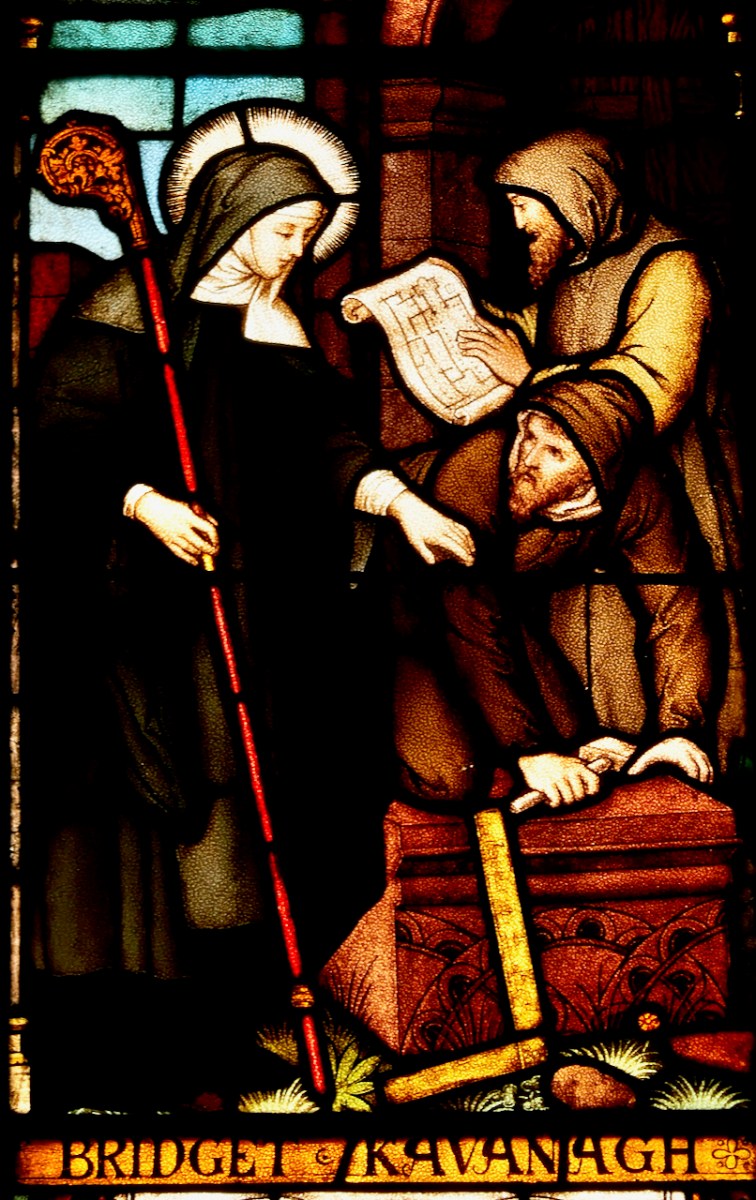

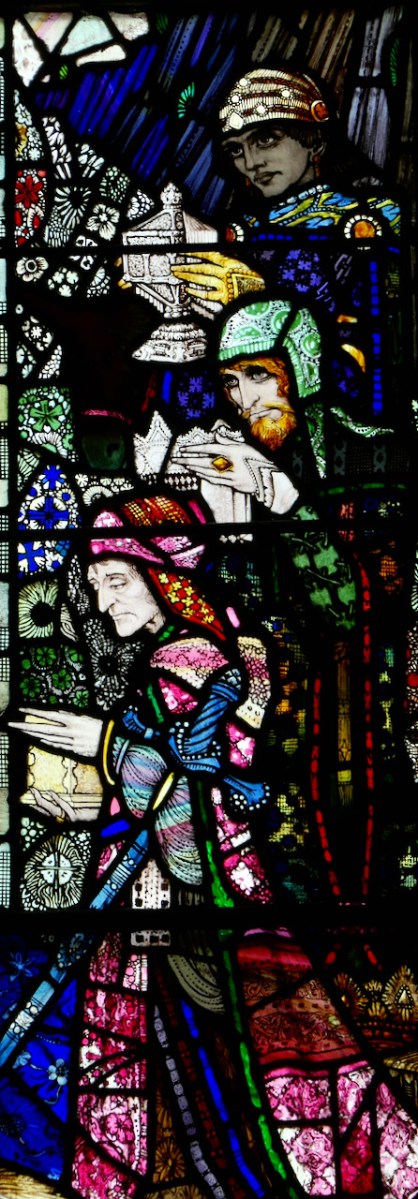

In St Michael and St John’s Church in Cloughjordan, Co Tipperary, the theme of the large, five-light, window is The Ascension with Irish Saints and St Michael and St James. Gordon Bowe designates this one a Harry Clarke (B). That means that this window was initially conceived and designed by him but executed by his studio under his close supervision. This is the first window we have come across, in this series, that is not wholly Harry’s own work, and this is a measure of how busy the Studios had become with Harry at the helm.

As in Terenure, Brigid is here as one of the Irish saints. She is depicted as very young, wide-eyed, and carrying a church which now looks more medieval than Romanesque (neither would have been appropriate to her era) and is probably a nod to the Cathedral in Kildare.

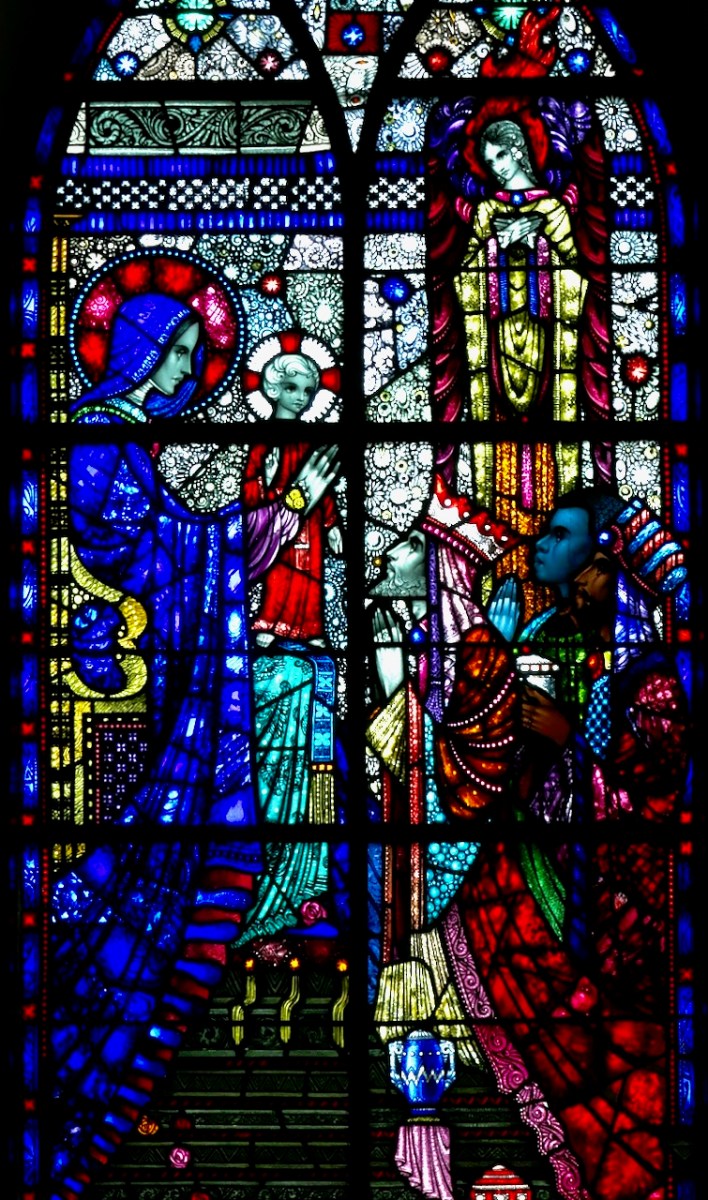

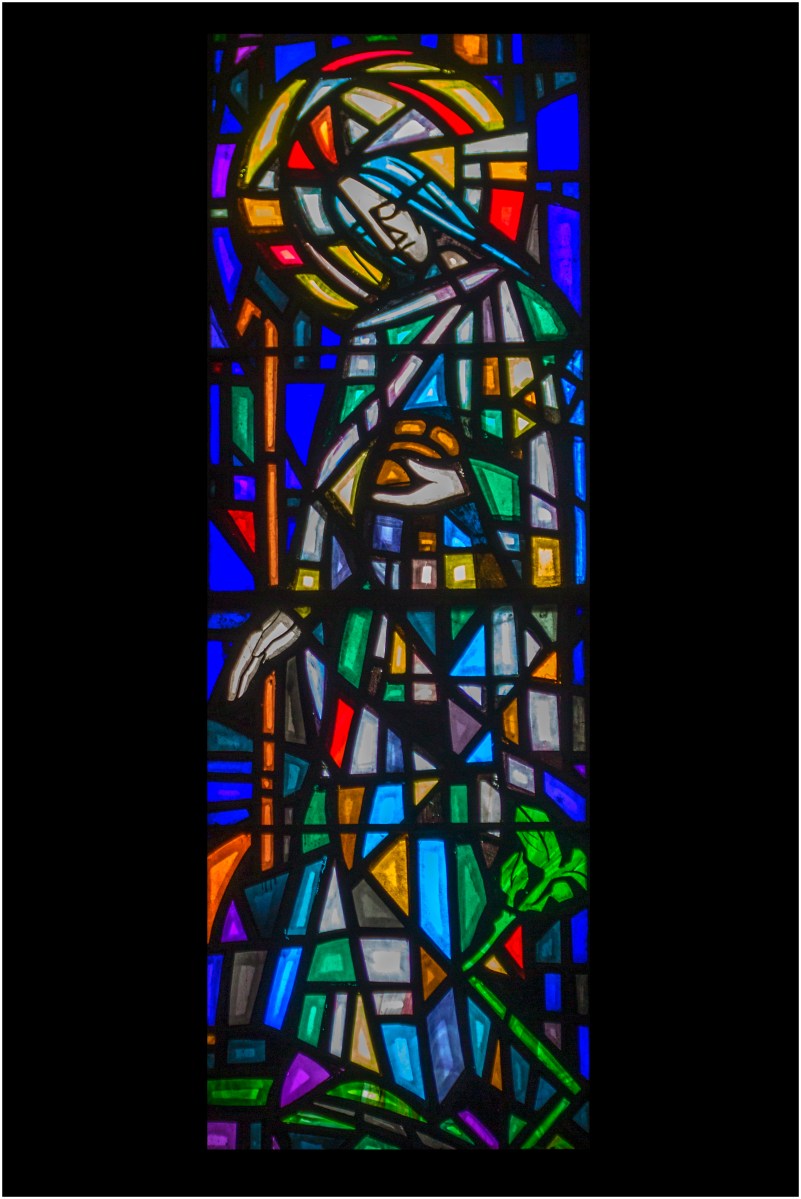

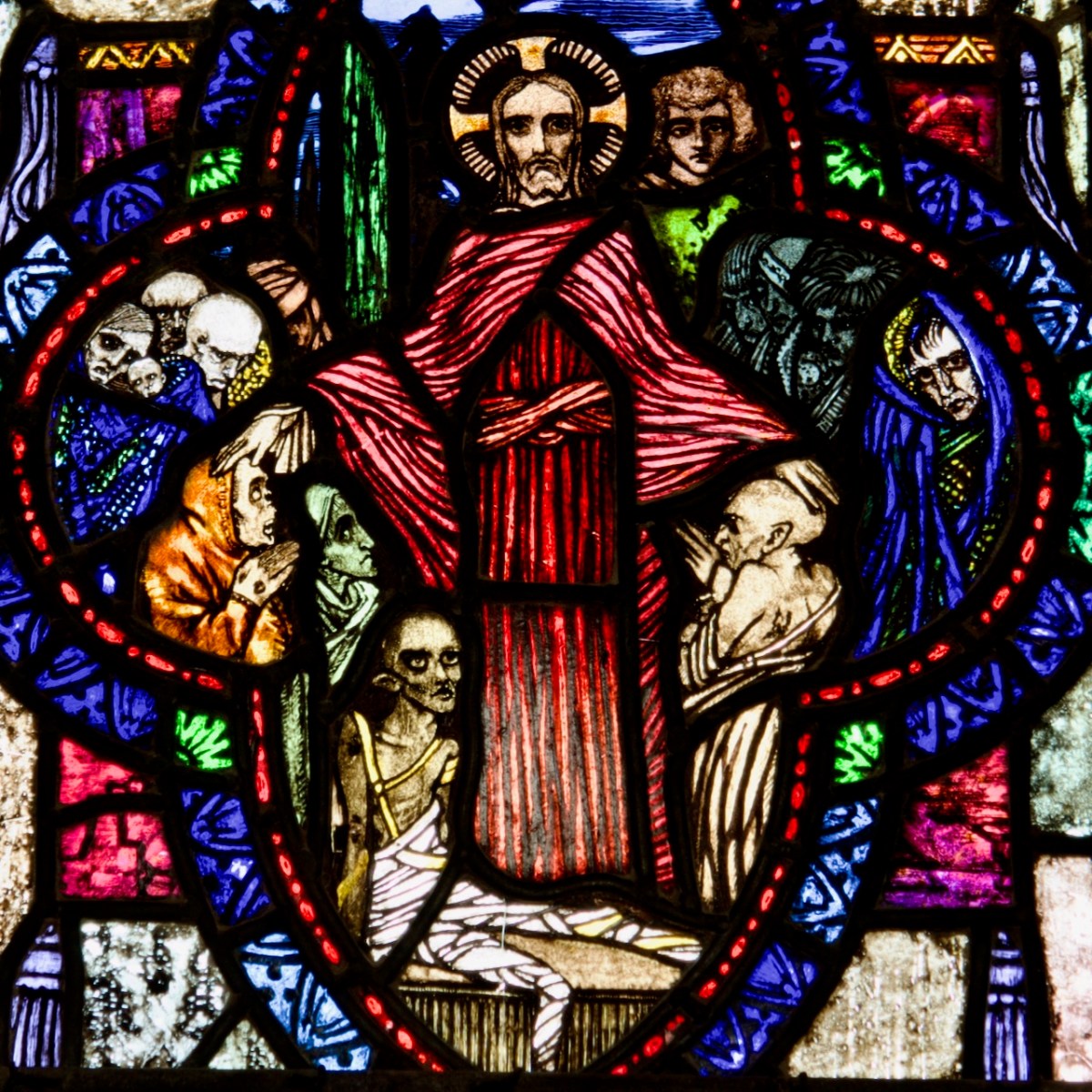

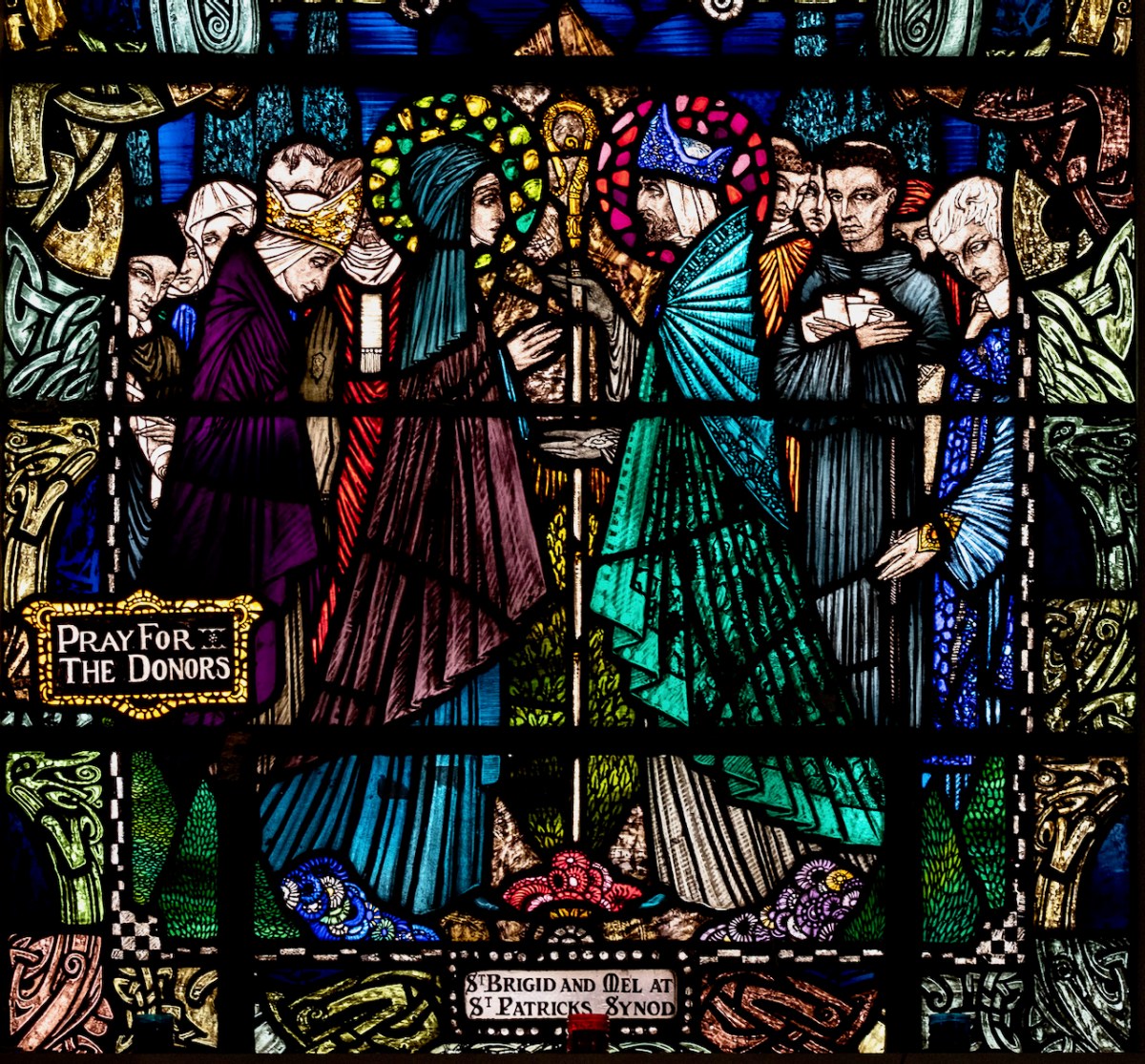

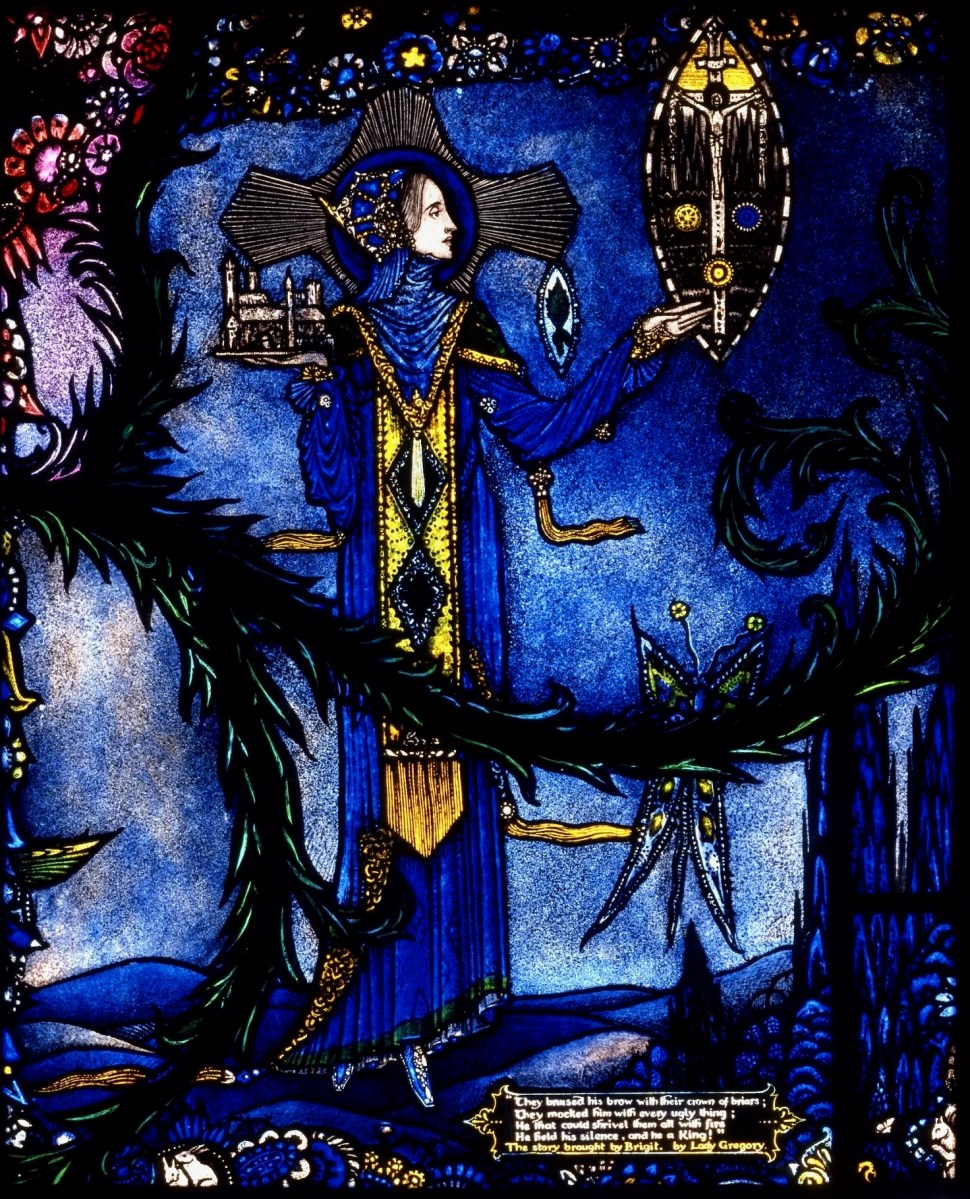

And so we come to the last Brigid that Harry ever did*. It is from the famous and controversial Geneva window, now in the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami. If you have not yet seen the marvellous documentary that Ardall O’Hanlon has made about this, I highly recommend you do. It’s available on the RTE Player as of this time of writing. The Brigid panel is among the less controversial images in the whole window. It’s based on a play by Lady Gregory called The Story Brought by Brigit. According to Marie T Mullan in her lovely book, Exiled from Ireland: Harry Clarke’s Geneva Window,

The play is a passion play, but it is based on the legend, popular in Ireland and Scotland, that St Brigit was present at the birth and crucifixion of Jesus. Brigit mingles with the crowds from the time of Jesus’s triumphant entry into Jerusalem until after his death. She is a foreigner, observing and commenting. She tells people she is Jesus’s foster mother and brought Mary and Jesus to Ireland to escape Herod. . . The icon of Christ Crucified is a the vesica, a shape used often in art for a picture within a picture, and has the traditional beaded frame. Brigit is absorbed in the icon.

Note Brigid’s golden scapular and elaborate headdress. Also the stylised butterfly and the little woodland creatures in the scene.

I think that’s a good place to stop. Harry did another Brigid, for the Oblate Fathers in north Dublin’s Belcamp Hall. This is a sorry tale in which the buildings, once left by the priests were subject to appalling vandalism and the windows are in storage, and haven’t been seen for years. This is tragic.

* Thanks to my friend Jack Zagar for the Photos of the Geneva Window.