This is an Evie Hone window from Blackrock in Dublin – Bridget, Mary and Jesus, and Patrick. Evie Hone is one of our greatest stained glass artists and helped to move the practice of stained glass into a more modern direction. To appreciate this, it is helpful to know a little of her background.

Our Lady of the Rosary, completed in 1948 for the Catholic Church in Greystones, Co Wicklow. While the figure is not cubist, the influence of that style is discernible

She was born in 1894 Dublin, a member of the extended Hone clan of painters and artists. A childhood accident left her disabled and in pain but also set the course for her life’s work by providing the consolation of sketching. She studied in Britain, Ireland and Paris, where she came under the influence of the Cubists, and also met her great friend and fellow-modernist, Mainie Jellett.

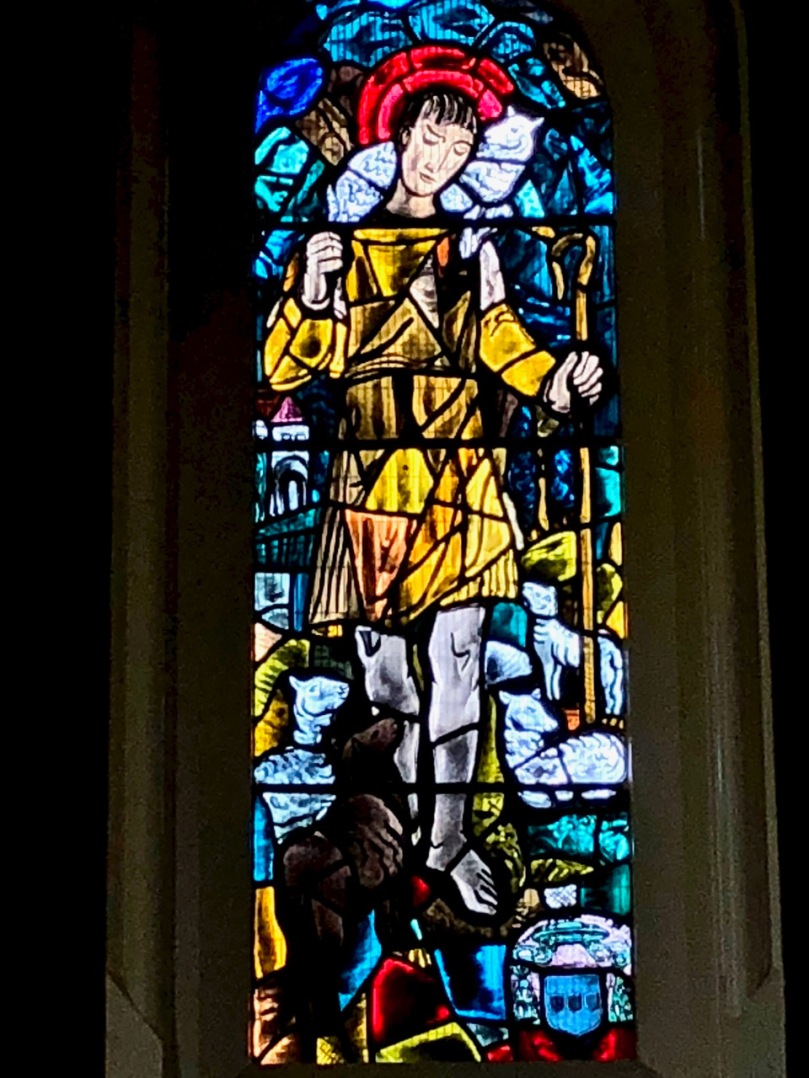

The Good Shepherd, also from Greystones

The two women applied to exhibit at the Royal Hibernian Academy but it was dominated by male traditionalists who refused to allow cubist paintings to be shown. They responded by exhibiting elsewhere and by starting a new organisation (the Irish Exhibition of Living Art, or IELA) for those interested in modern art. At first critics ridiculed this new style of painting but young artists were enthusiastic and gradually she and Mainie “introduced modern art to Ireland.”*

Evie Hone stained glass on display in the new, and very popular Stained Glass Room in the National Gallery

Evie was deeply spiritual, at one point joining a community of Anglican nuns and eventually converting to Catholicism. Moving away from painting to stained glass she trained under Wilhelmina Geddes and eventually joined An Túr Gloine in 1935. Her stained glass work was never strictly cubist, although the influence was traceable, but it was thoroughly modern.

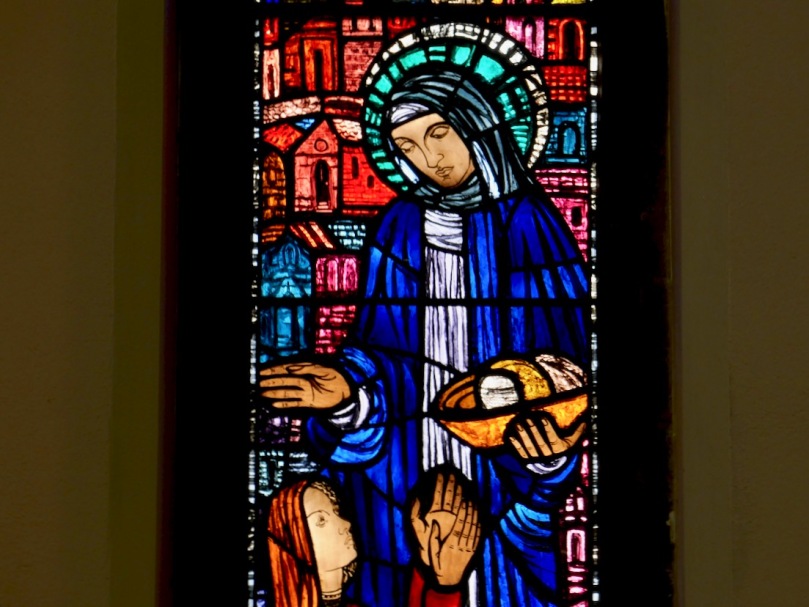

This is her Bridget window for Loughrea Catherdral, completed while she was a member of An Túr Gloine and at the beginning of her development as a stained glass artist. It is noticeably a more conservative and less modern treatment – contrast it, for example with Bridget from the Blackrock Church

Nicola Gordon Bowe, in her entry on Evie Hone in The Encyclopedia of Ireland (edited by Brian Lalor) says of her work for An Túr Gloine, she was designing and painting mostly figurative windows using a powerfully innovative vocabulary of deep smouldering colour and loose expressionist brushwork.

Two small windows from Cloughjordan Church (Co Tipperary) depict Mary and Joseph. These windows were among her last, and are beautiful in their restrained style and subdued palette

From 1944 she worked in her own studio at Marley Grange in Rathfarnham. Gordon Bowe, again: In ten densely packed years she introduced a new, loosely painted, resonantly coloured, and sombrely religious treatment. We are fortunate that a short documentary recorded this period on her life and work. It also functions as a primer on stained glass!

About the same time, in 1952, her friend and fellow-artist, Hilda van Stockum painted her in her studio, capturing her complete absorption in her work. This image comes from Marie Bourke’s paper* and is a copy of a photograph from a National Gallery Catalogue. The original painting is in the National Gallery.

What is most striking about her work, in contrast to her colleagues at An Túr Gloine, is how painterly it is. Using a restrained palette, with occasional bursts of bright colour, she creates quiet and reverential portraits of her sacred subjects. Modernity is obvious, but she herself claimed that the major influence on her work was medieval Irish carvings. If this was true, it was certainly mediated through an expressionist sensibility.

Bridget – detail from the Blackrock window

Evie Hone died in 1955. She has left an impressive legacy of paintings and stained glass windows. I have only used photographs that I have taken myself of windows that I have visited, but there are many more waiting to be explored.

* The quote, and also the photograph of the painting of Evie Hone in her Studio are from Evie Hone in Her Studio: Hilda Van Stockum’s Portrait, by Marie Bourke, in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 86, No. 342 (Summer, 1997), pp. 165-174. The paper is available on JSTOR