We went to Ballyvaghan, County Clare so that I could take part in the Concertina School run by Maestro of that instrument – and Clare man – Noel Hill. I have played concertinas for over 40 years but never in the ‘Irish’ style: here I am in Ireland so – in my seventh decade – it’s back to school for me! The concertina – a small squeezebox – has a long history in Clare, and in Ireland. It was pioneered by an Englishman, Charles Wheatstone, in the 1800s. Wheatstone’s real fame came as co-inventor – with William Cooke – of the electric telegraph which was arguably the forerunner of all our present day telecommunication systems (so thank you, Wheatstone, for my iPhone) but he was also prolific in his invention and improvement of many other devices, including musical ones. He took the Mundharmoniker – a German metal-reeded mouth blown instrument and turned it into the mouth-organ we know today; he then used the metal reeds and leather bellows to develop the concertina itself, a very portable instrument which has a tone and range similar to the violin. High quality concertinas bearing the Wheatstone name are still being made, as are many others, but it was the ability to mass produce these instruments at a low cost (far lower than the fiddle) which ensured their popularity in Victorian drawing rooms and in ale houses, dance halls and kitchens.

The concertina can be loud: the smaller the area of the bellows on a squeezebox, the more powerful the pressure that can be exerted on the steel reeds. Consequently the instrument has a very bright tone which carries above most others and is therefore ideal for accompanying dances in noisy rooms – or certainly was, before the days of amplification. Imagine a flag-stoned floor in a parlour or outhouse with a lively Irish set in full swing: the sound must have been fairly overwhelming, and it needed a loud instrument to be heard above the melee. Clare was and is a musical county, and gatherings for dancing (and socialising and matchmaking) were a major past-time in rural districts. The concertina was a boon on these occasions and is now an instrument forever associated with the area and its musicians. Because of its volume and its strident possibilities, the concertina has become known as ‘the Clareman’s Trumpet’.

I could write a whole post on the many varieties of concertina which have been developed since Charles Wheatstone took out his patent in 1829. Suffice it to say that you are likely to encounter only two types in your normal travels: the English Concertina – where each button plays the same note regardless of which direction you are moving the bellows – and the Anglo Concertina – where each button gives you two different notes: one on the push and another on the pull – similar in principle to the modern mouth organ. My instrument is the Anglo, and this is also the one most commonly (but not exclusively) found today in Irish Traditional Music.

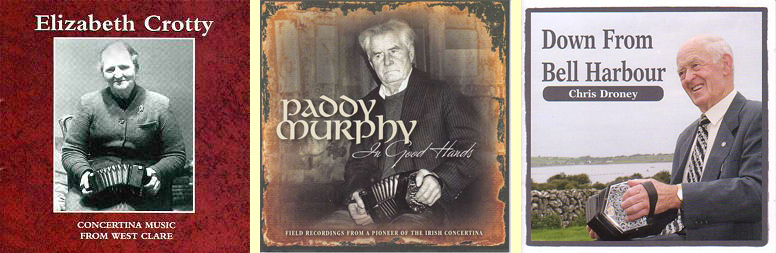

No mention of the concertina in Clare would be complete without a note on Mrs Elizabeth Crotty of Kilrush. She lived between 1885 and 1960 and was famous in her day as an Anglo player. Crotty’s pub is still there in Kilrush, and still in the family. I went there on my first visit to Ireland almost exactly 40 years ago. Mrs Crotty’s memory had not faded then. I played in the pub on that visit and was told (by her daughter) that this was the first music that had been heard in the pub since the First Lady of the Concertina had died. It’s a different matter today: there is live traditional music most nights in Crotty’s, and in so many other establishments all over the county. More Clare concertina names include Paddy Murphy (who I was fortunate enough to meet and hear at a wild and remote session on that first visit), Chris Droney of Bell Harbour, still playing in his eighties, and many another.

No mention of the concertina in Clare would be complete without a note on Mrs Elizabeth Crotty of Kilrush. She lived between 1885 and 1960 and was famous in her day as an Anglo player. Crotty’s pub is still there in Kilrush, and still in the family. I went there on my first visit to Ireland almost exactly 40 years ago. Mrs Crotty’s memory had not faded then. I played in the pub on that visit and was told (by her daughter) that this was the first music that had been heard in the pub since the First Lady of the Concertina had died. It’s a different matter today: there is live traditional music most nights in Crotty’s, and in so many other establishments all over the county. More Clare concertina names include Paddy Murphy (who I was fortunate enough to meet and hear at a wild and remote session on that first visit), Chris Droney of Bell Harbour, still playing in his eighties, and many another.

But Clare’s musical connections are not limited to the concertina: as we travelled around we became very aware of how important is music in all its varieties in this windswept, largely treeless but peculiarly beautiful part of the island. There are instrument makers: Finola grew up with Martin Doyle in Bray: he’s now one of the top producers of hand-made wooden flutes in the world! We visited his workshop – a well-equipped timber shed on the edge of the Burren. It was a great reunion: while the stories were in full flow in walked Christy Barry, renowned traditional flute player – also a Clare native, to join the chat.

I mustn’t forget Martin Connolly, first class button accordion maker from Ennis, nor my all-time Irish music hero Martin Hayes (perhaps there’s something about the name Martin?) renowned fiddler and Director of the Masters of Tradition Festival every year down here in West Cork: he hales from East Clare.

The roll call is endless, but perhaps pride of place (for now) should go to Willie Clancy, not a concertina player but a master of the Uillean Pipes. He has made famous the name of his home town, Milltown Malbay, where they have honoured him with a fine bronze statue. Every year in July around 10,000 people descend on the small West Clare town and swell its normal population tenfold. There are workshops, classes and concerts but, most of all, there is just constant music – in pubs and cafes, and on every street corner: the craic is mighty!