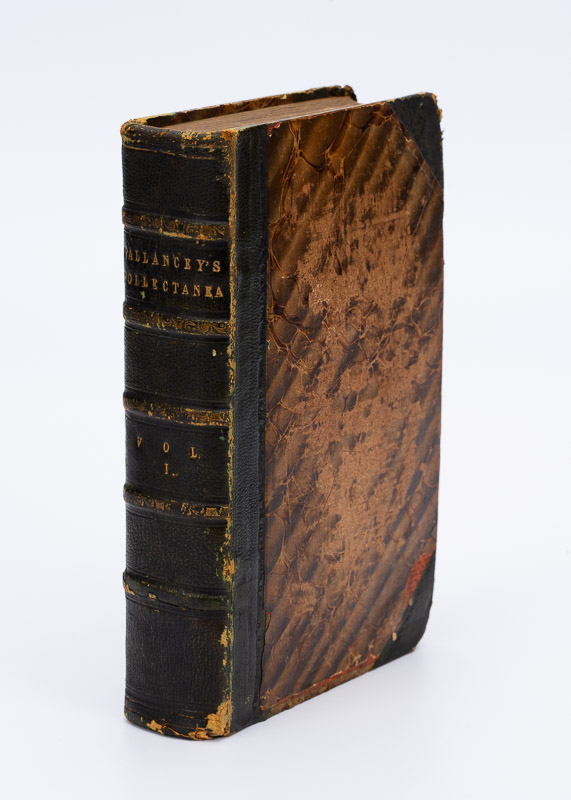

Though often derided by his contemporaries and later critics for his more outlandish theories, Vallancey arguably did more than almost anyone else in the late 18th and early 19th century to stimulate interest in Irish archaeology and history. Much of this was accomplished through the essays and papers he published in his Collectanea, through which he reached an educated audience.

Let’s take a deeper dive into the Collectanea (pronounced, I have found, collecTAYnea) now. But be warned – these are my own quirky interests on display here, not a scholarly analysis. I can’t always account for what catches my attention, but isn’t that the real delight of browsing a set of volumes like this – the treasures you will unearth? The other pleasure is just holding it – the feel and smell of such old books, and getting used to the typeface.

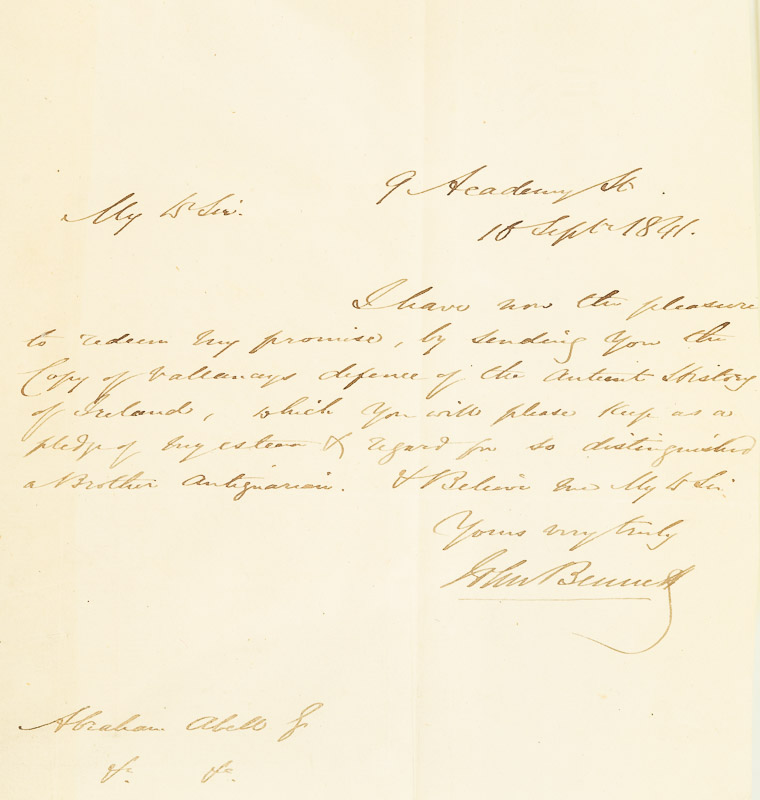

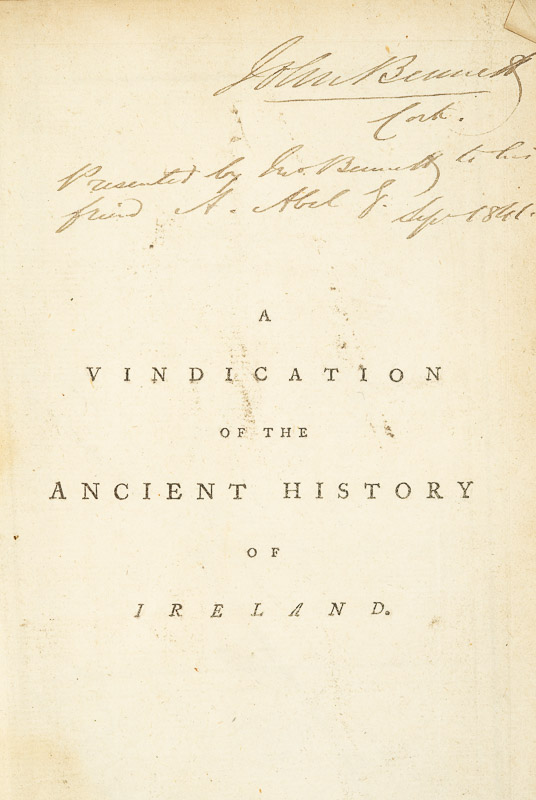

There’s another reason too – the provenance of the set. Hidden inside Volume IV is a telling letter (above) that proves that this set originally belonged to Abraham Abell (1783 – 1851). A vital figure in the antiquarian community of Cork, Abell was a true eccentric who amassed an enormous library, burnt it all in 1848, and then started again to amass thousands more. In his retirement, he rented a room in the Cork Institute (now the Crawford Art Gallery) where he lived out the rest of his days with his thousands of books stacked from floor to ceiling.

We know that this set of the Collectanea belonged to his first library since it was given to him in 1841 by John Bennett, and that somehow it was not consumed in the burning. I have read two accounts of the burning – one that he did it in a depressive episode, the other that he did it to make room so he could start afresh. However it happened, it’s a minor miracle that the set has survived that cataclysmic event.

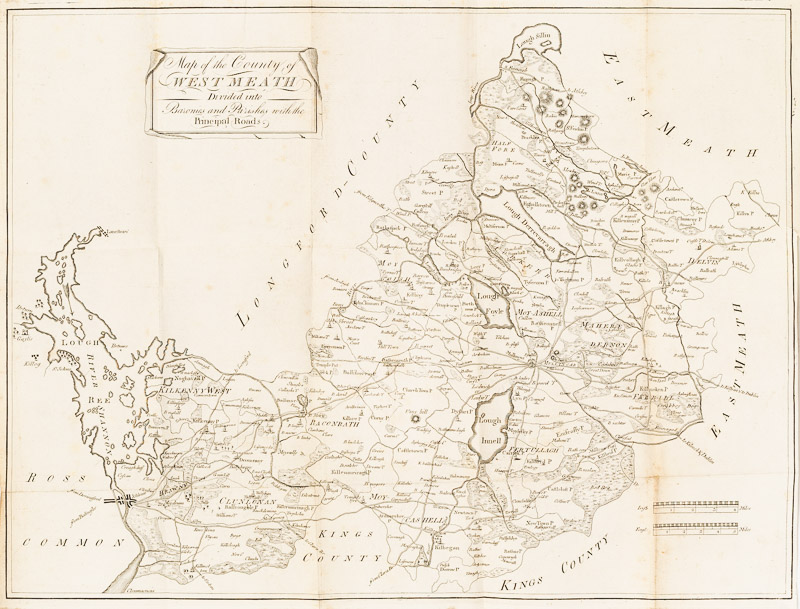

Vol 1 begins with A Chorographical Description of the County of West-Meath,1682, by Sir Henry Piers, accompanied by a map of the county. Vallancey published this in 1770 and it is likely that the map dates to then rather than the 1680s, when map-making was far more rudimentary. Chorography, a word not much in use nowadays refers, according to Wikipedia, to the art of describing or mapping a region or district.

While some of the introduction especially refers to the geographical features of the country, much of it, in fact is made up of descriptions of customs, ancient battles, significant places (e.g. Cat’s Hole Cave), ruined monasteries and saints, ways of making a living, and accounts of the degenerate English and oppressive landlords.

Piers belongs in the ranks of those who believe the English civilised the Rude and Barbarous Irish, although he admits that some are not quite civilised to this day. By degenerate, Piers meant Englishmen who had ‘gone native’, married Irish women, spoke Irish and fostered their children with Irish families. From men this metamorphosed, he queries, What could be expected? He admits that English Kings neglected Ireland and that there was substantial corruption among officers of justice. The Irish, he says are given to learning and hospitality and the women are generally beautiful, and love highly to set themselves out in the most fashionable dress they can attain. However, the landlords of old, by which he presumably means the Irish clan heads, were and still are great oppressors of their tenants.

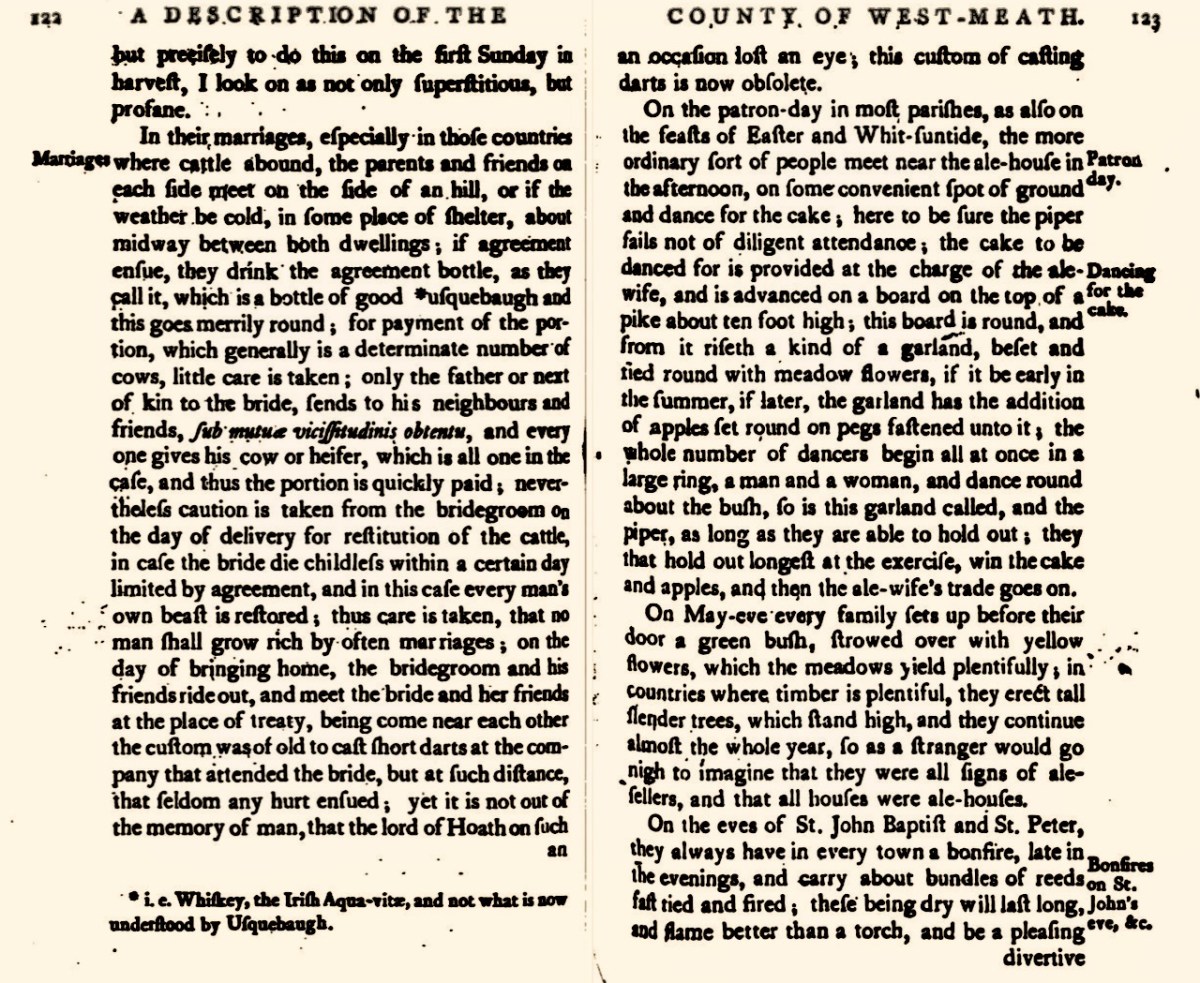

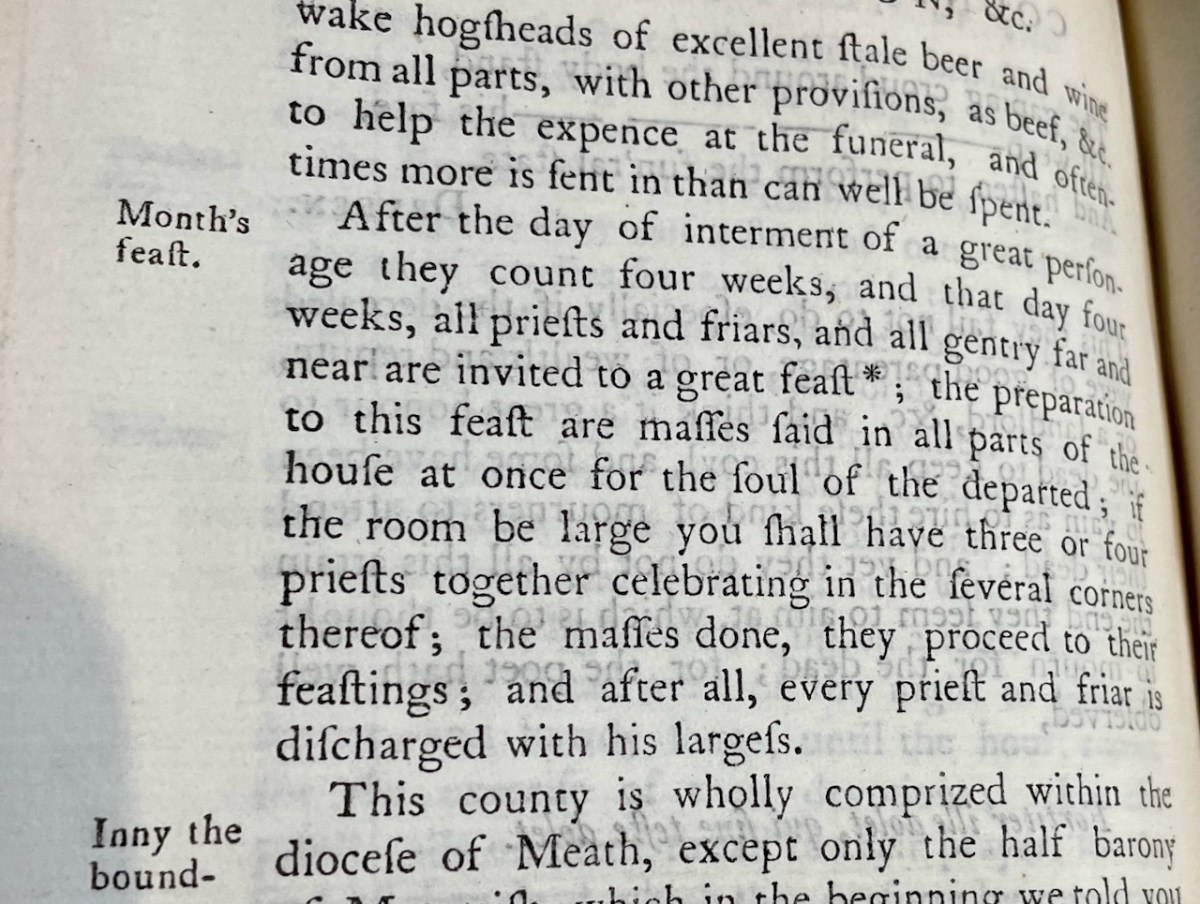

He describes agricultural practices (very dysfunctional and leading to many quarrels) and Bearded Owen’s Law, by which shares in bog-cutting are apportioned, and the practice of driving the cattle through water once a year. Marriages (above) are negotiated between parents and friends on each side. He writes about the May bush, bonfires on St John’s Eve, wakes more befitting heathens than Christians, and the practice of the Month’s Mind (below) which involved a great feast and many masses said in the house, after which every priest and friar is discharged with his largess.

I’ve only picked out a few details from the essay on Westmeath, but you can see from these examples what an incredibly valuable this resource is. We have very few descriptions like this of what life was like in 17th century Ireland, and the fact that Vallancey recognised its importance and published it says much about his appreciation for Irish customs and lore.

The second document is a Letter from Sir John Davis written to Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury (above) in 1607. This was shortly after the Battle of Kinsale (1601) which marked the end of the power of the old Gaelic families. In this letter, Davis describes the state of the counties of Monaghan, Fermanagh and Cavan, in preparation for a visit by the earl.

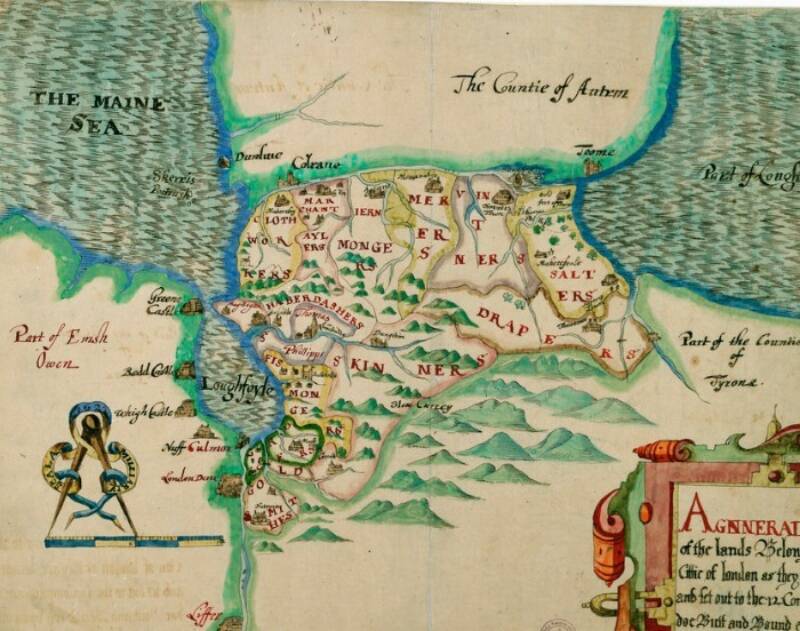

In 1607 Hugh O’Neill (above) had been restored to his estates in Tyrone following the Treaty of Mellifont, but was to lead his followers into exile in 1607, an act known as The Flight of the Earls. This cleared the way for the English to plan a plantation – the Plantation of Ulster became in effect what established the modern jurisdiction of Northern Ireland. And that’s exactly what is described in the letter – who owns what land (including clerical lands) and what should be done with it. It’s crucial to understanding the development of modern Ulster. That’s a plantation map, below, but not from this volume. It lays out what land the haberdashers could have, or the skinners or the drapers.

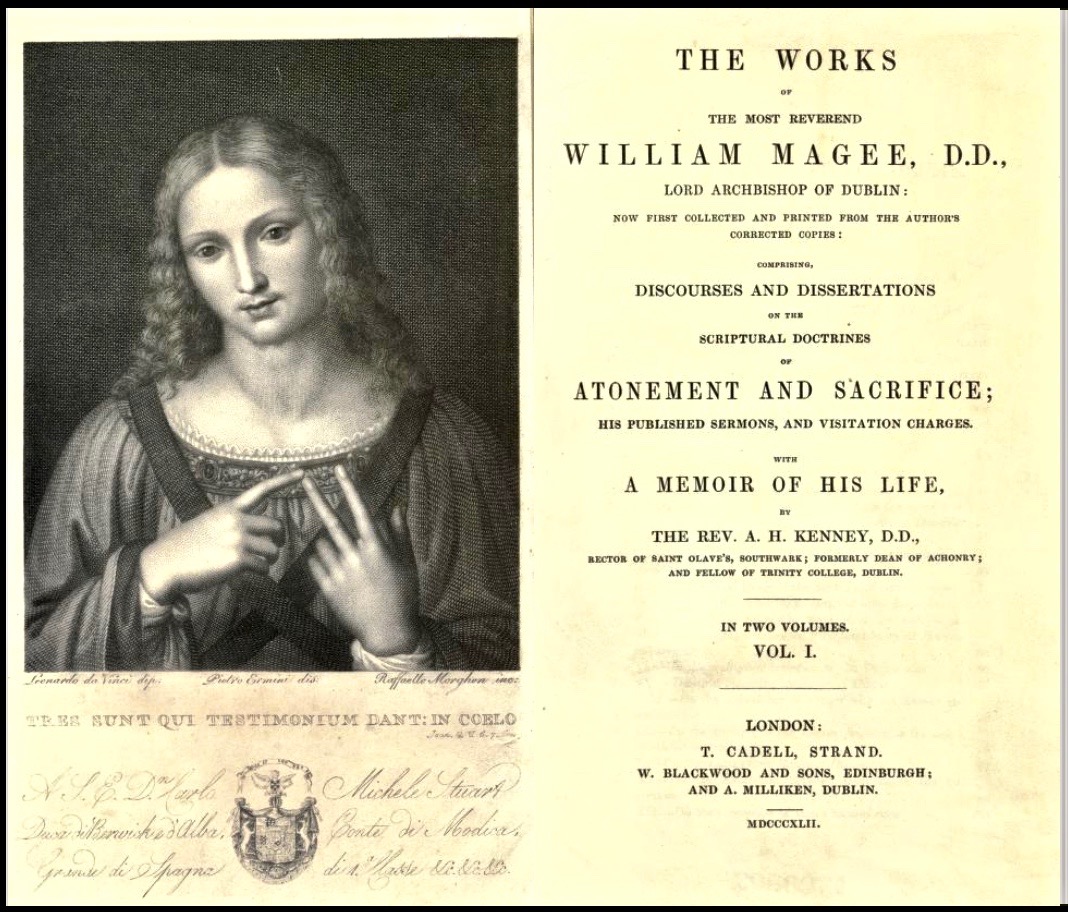

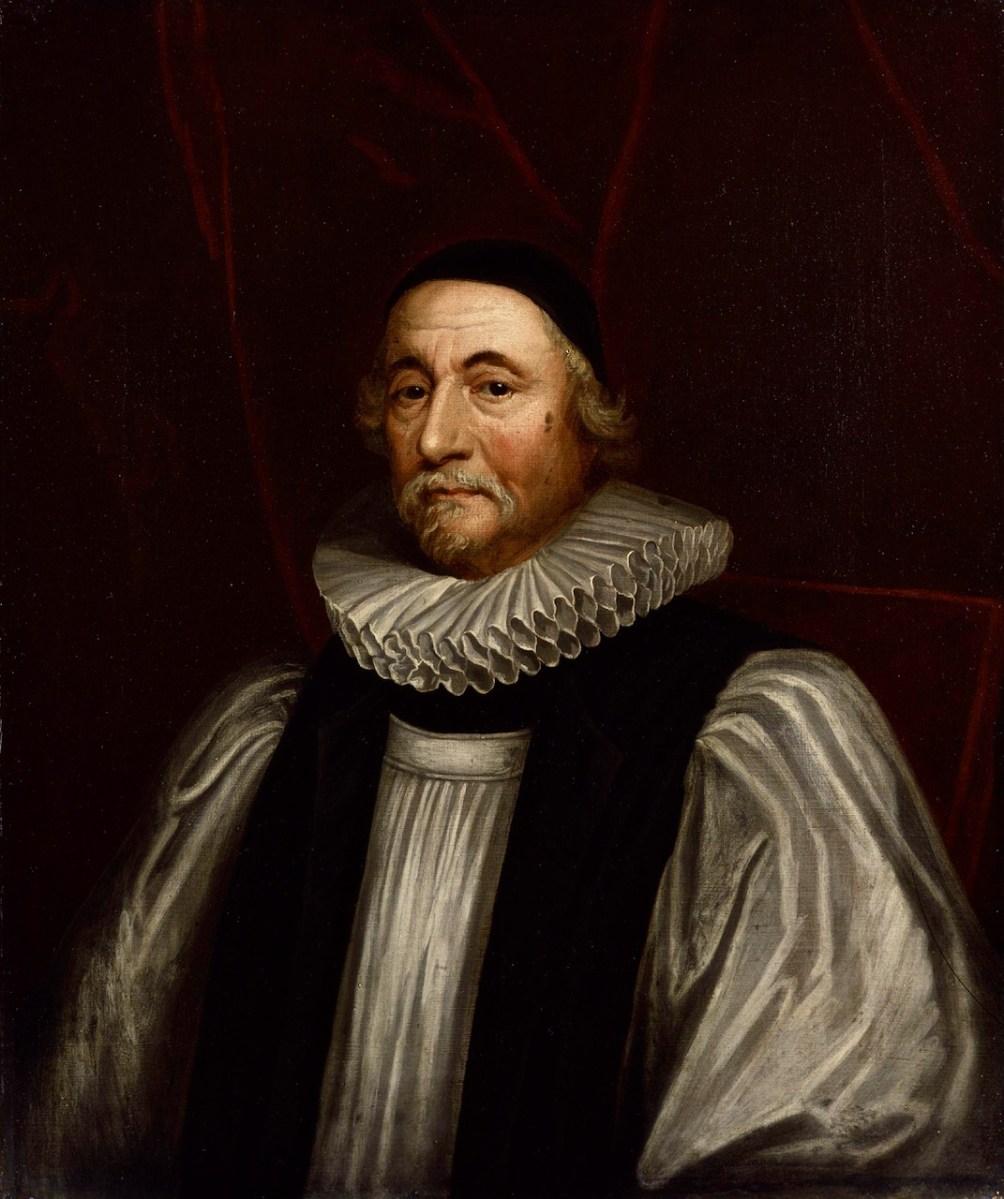

And next – who have we here? It’s none other than Archbishop James Ussher (1581 – 1656), later the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland. This is the same man who established to his own satisfaction that the world was created on 6 pm on 22 October 4004 BC. Harmless speculation, you say? Alas not so – there are many people in the world today who still believe this, and it was certainly a commonplace belief up to the 20th century.

[Aside – what is extraordinary to me is that Trinity College still has his portrait proudly on display (below) in their Exam Hall. Meanwhile, George Berkeley is being erased from their history – correctly, perhaps – but for the same crime of being ‘a man of his time.’]

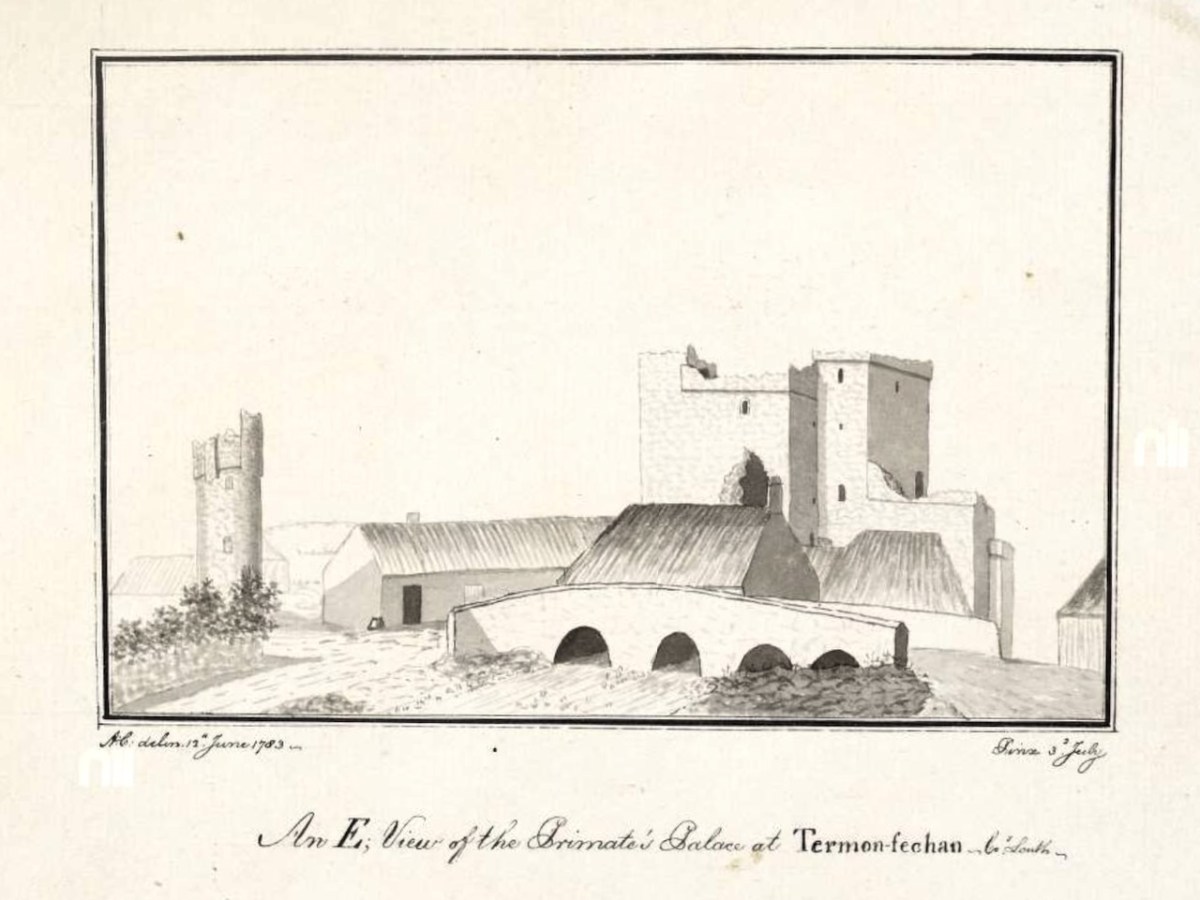

Ussher’s piece was written originally written in his own hand in 1609. It is titled Of the Origin and First Institution of Corbes, Erenachs, and Termon Lands. All these were common terms on the early Irish monastic system, to denote land holdings and those who held them. For example, a Termon was thought to be a sanctuary, hence the town of Termonfeckin was originally Tearmon Feichín, or St Feichín’s Sanctuary. Corbe was more usually given as Coarb. In the period following the dissolution of the monasteries, and the plantations that followed the Battle of Kinsale, there was a need to define these terms so that the land could be divided among English settlers. This is a very difficult treatise, written half in Latin, which lays out the meaning and origin of the terms and also the men who held the lands, to whom they paid rents or annuities, or owed labour. Ussher disingenuously disclaims any interest in this treatise besides having described without any partiality the meaning of the terms.

However, a little reading in the late lamented Peter Harbison’s Cooper’s Ireland yields the information that Ussher, in fact, had possession of Termonfeckin. Here’s what Harbison says:

This ‘palace’, referred to as ‘Termonfechan’ by Austin Cooper, was named after a monastery that once stood on this site, founded by Saint Fechín of Fore in the seventh century.

But the reason why the primate – that is, the Archbishop of Armagh – should have a palace here at all was not out of homage for this early Irish saint. It had much more to do with the religious politics of the later mediaeval period, when the Archbishop – usually an Englishman by birth – was surrounded by native Irish whose language he did not understand. He felt much safer when he could get away from his See at Armagh and reside at Terminfeckin, the southernmost tip of his Archdioceses, and its nearest point to the centre of English power in Dublin some 35 miles away.

The siege mentality of those within is reflected in the small, defendable window slits inserted in the severe looking wall face, as seen in Coopers drawing…Its last inhabitant had been…Archbishop James Ussher.

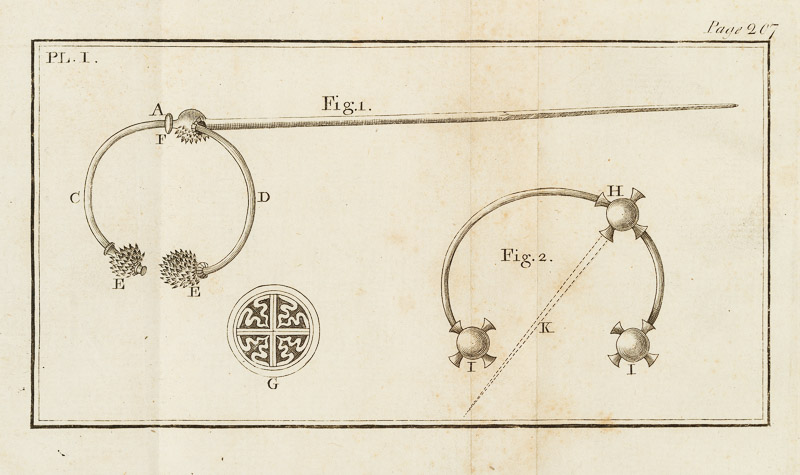

A Short Account of Two Ancient Instruments, by Vallancey follows. Here we can see many references to Phoenicians and Egyptians. He had recourse to the writings of Homer to inform us that the weapons of the Trojan war were made of copper, thus, of course, implying a Classical date for them. He rambles on about Sabean priests, Arkite forms of worship and fire feasts of Baal, before finally getting to describe the instruments – neither of which appear relevant to the previous discourse. In this case, the instrument are of silver. There is no attempt to interpret their use, and they certainly don’t look like musical instruments but rather perhaps cloak fasteners.

I had intended to cover all of Vol 1 in this post, but I am not even half-way through. I will have to get a lot better at skimming and summarising if I am ever to emerge from this mountain. But I am hoping that this gives you a flavour of not only the diversity but also the value of the Collectanea. In the first 250 pages alone we have had original documents, not by Vallancey (except for the ‘Instruments’) but collected and published by him, that are invaluable to the understanding of Irish history and culture. This – the collecting, preserving and publishing important documents, as well as listing where others can be found (see Part 1) – may in fact have been his greatest contribution to Irish scholarship.

I’ll finish with an illustration from one of the Volumes – it is not identified and is certainly not by Vallancey. In fact it looks like one of Beranger’s. Perhaps one of our readers might know what ruin this is. [EDIT: identified! See comments below] The lead image, by the way – the portrait of Vallancey, is taken from VH Andrews’ essay on Charles Vallancey and the Map of Ireland (see previous post) and is described as from an oil painting by Solomon Williams.