It may seem strange to commemorate ‘The Great Hunger’ – the Irish famine years of 1845 – 1849 – with an art exhibition. Yet, when we look back on that time, 170 years ago, the only possible reaction to the starvation, mass graves and wholesale emigration which happened within the boundaries of the great British Empire (and not too far from its capital) is raw emotion: it’s a subject that can’t be intellectualised. The 1.4m high work above, by bog oak sculptor Kieran Tuohy from County Galway, is an example of an emotional response: hands hold up a group of anonymous and vulnerable figures.

John Coll’s piece, Famine Funeral (above), is also evocative. The exhibition at Uillinn in Skibbereen opened on Thursday and attracted a large and excited crowd; since then, record numbers of visitors have come daily to the town’s iconic gallery. The work is all from Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum at Quinnipiac University in Connecticut, which has the largest collection of Great Hunger-related art, and will be shown here in West Cork until 13 October.

Skibbereen was one of Ireland’s worst affected towns during the famine years, which makes the visit of this exhibition entirely appropriate. It has shown that our gallery is able to display a collection such as this of the highest calibre, giving the community an asset unique in rural Ireland. All credit must go to the Director, the staff and the Board of the West Cork Arts Centre who have worked hard to raise funds and make all this possible. Also Cork County Council have to be commended for finishing off the flood relief works and the associated landscaping around the gallery in time for the opening: Uillinn now features a significant architectural setting in the town centre. The photographs above were taken outside and inside the building on opening night.

With some exceptions (Glenna Goodacre’s bronze – Famine – is one, above), I am only showing extracts from the works in this review. The whole exhibition is so powerful that it has to be seen in real life, so I’m hoping that these tasters will persuade you to visit.

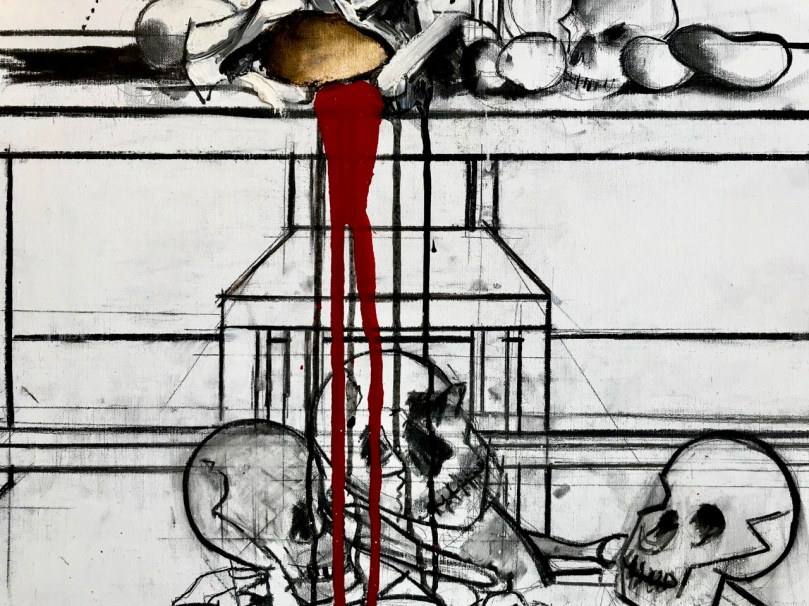

The artist Micheal Farrell (1940 – 2000) is well represented in the Quinnipiac Museum and some of his works have come to Skibbereen, including the enormous Black ’47 (4.5m wide and 3m high) a detail of which is shown in the upper picture above, with a detail from The Wounded Wonder below it. The Irish Times described Farrell’s largest work:

. . . Farrell’s canvas seems to float on a wall by itself in the museum. It is the trial of Charles Trevelyan, the British official who was in charge of Famine relief. Trevelyan stands in a searchlight shaft, a hand on one hip, embodying the arrogance of empire. The prosecutor gestures towards Irish skeletons rising from an open grave, evidence against the man who called the Famine “the direct stroke of an all-wise Providence” and a “mechanism for reducing surplus population” . . .

Dorothy Cross – Basking Shark Curragh (a comment on the vulnerability of Irish coastal communities in famine times) with Micheal Farrell’s The Wounded Wonder and Kieran Tuohy’s Thank You to the Choctaw beyond.

Also extracts: the upper image is from a powerful bronze work – The Leave-Taking by Margaret Lyster Chamberlain – and the lower image is part of The Last Visit by Pádraic Reaney.

Lilian Lucy Davidson’s Gorta (upper image) and Hughie O’Donoghue’s On Our Knees (lower) are both powerful statements on hunger and our own attitudes to the problems of the contemporary world.

At the opening of Coming Home – Art and The Great Hunger – Cyril Thornton, Chairman of the West Cork Arts Centre made the following observations:

. . . We are formed by our memories, experiences, the voices of our ancestors carried through the ages that carry into the soul of who we are. When we refuse to listen to the voices of the past or learn from our ancestor’s achievements and mistakes we lose a piece of our soul.

In a world that appears to becoming more soulless and intolerant it is now more important than ever to shine a light on our past for another generation, not to blame or recriminate but to help them to shape a world where humanity will never accept that injustice, poverty or hunger can be imposed on those in need of support.

The memory of the death of over 1 million people and the subsequent emigration of another 1.5 million defines us as a nation. The bringing home of this exhibition in many ways is a cultural reconnection. Art in all its form captures emotions and feelings, this exhibition in so many ways captures the tragic emotion of An Gorta Mór – The Great Hunger . . .

Detail from William Oliver Williams The Irish Piper 1874. Although painted after the ravages of The Great Famine this picture is said to imply that, despite hardship, the joyful side of Irish life was always irrepressible . . . whatever the occasion there was music and dancing . . . Below – powerful juxtaposition: a Rowan Gillespie figure seen against West Cork artist William Crozier’s Rainbow’s End.