Our journeys in search of important Irish archaeology can take us a long way from home. Today’s subject – the impressive Rathgall Hillfort – is located in County Wicklow, on the east side of the island. But it is well worth a long journey: its size is impressive – it occupies an 18 acre site. And the history of the place goes as far back as the Neolithic age. We visited on a brisk spring day, when the clouds were determined to contribute to our appreciation of this monument.

The size and longevity of this hillfort push it into a rare category. The substantial central rampart of stone walling is medieval, but the outer rings of stone and earth appear to have considerably earlier dates.

. . . Rathgall was a site of quite exceptional importance in the centuries spanning the birth of Christ, an importance that was clearly pan-European. The variety of structural information that the excavation yielded is unprecedented in the Bronze Age and the extraordinary concentration of artifactual evidence from the site has not been matched elsewhere in the country. Rathgall opens a wide range of questions concerning, not merely the nature of the Ireland’s later Bronze Age, but also the role of the hillfort in contemporary cultural developments . . .

Professor Barry Rafferty 2004

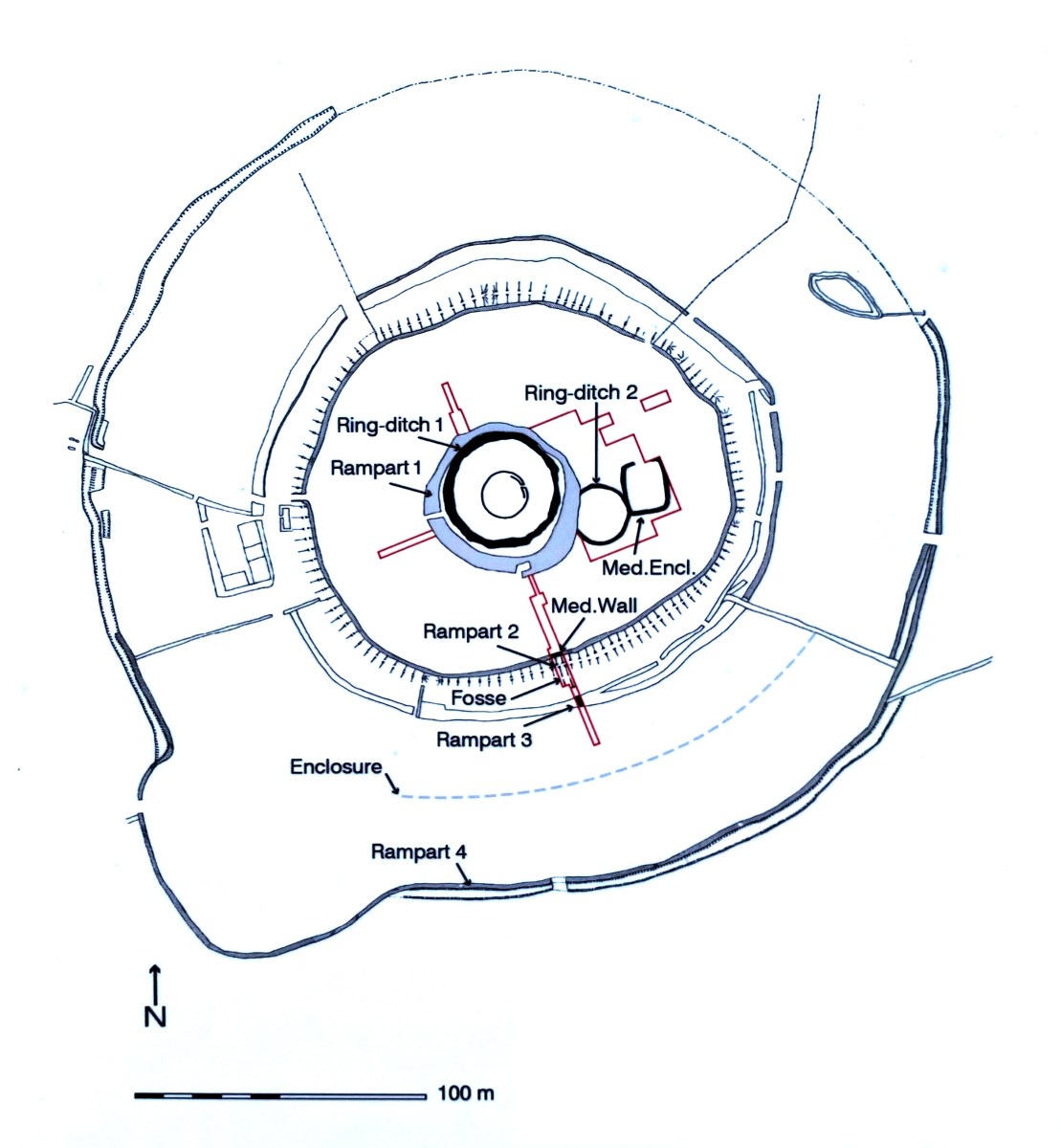

Plan of the hillfort and surrounding earthworks taken from the site notice board. Red lines indicate the site excavations. This board states that:

. . . Rathgall Hillfort is a hilltop settlement enclosed and defended by four concentric ramparts which can be dated to the early and middle Neolithic period . . . The outer three ramparts are stone and earthen banks and are likely to be prehistoric in date. Within the central enclosure there is evidence of metalworking, a cemetery and a round house; all dating to the Late Bronze Age . . .

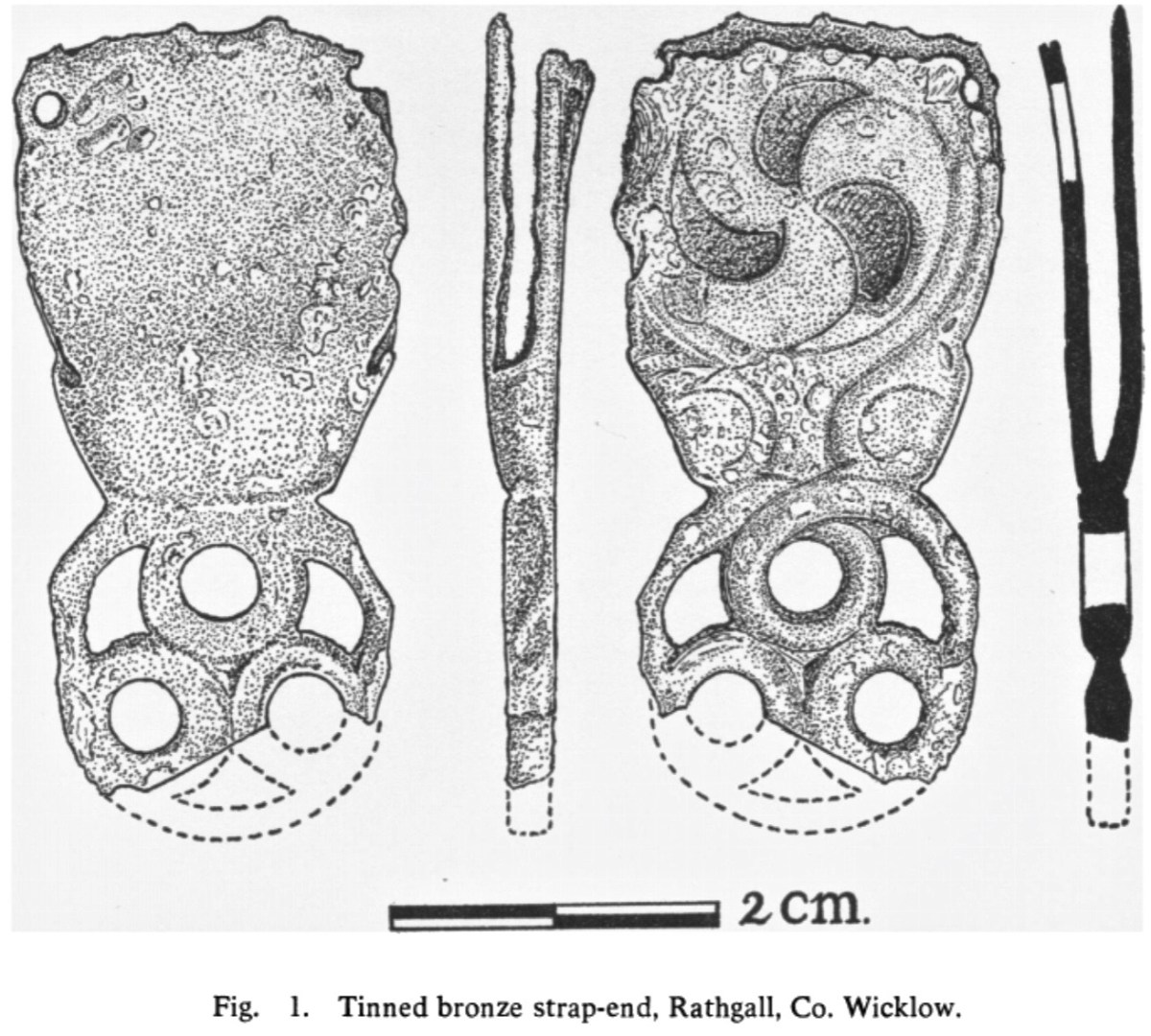

The two photographs above are taken from the time of archaeological investigations which commenced in 1969. The results of those excavations, which covered a number of years, have yet to be formally published. [Late edit: Elizabeth Shee has informed us that the findings will be published this summer by Wordwell, through the work of Katherina Becker of UCC. Many thanks, Elizabeth, we will look our for that]. The investigations found evidence that this was the site of an important and busy Bronze Age factory for metalworking (axe and spearheads, swords) and for pottery, jewellery and glass beads. In total over 50,000 pottery fragments were found, as well as 3,000 bronze and gold artefacts.

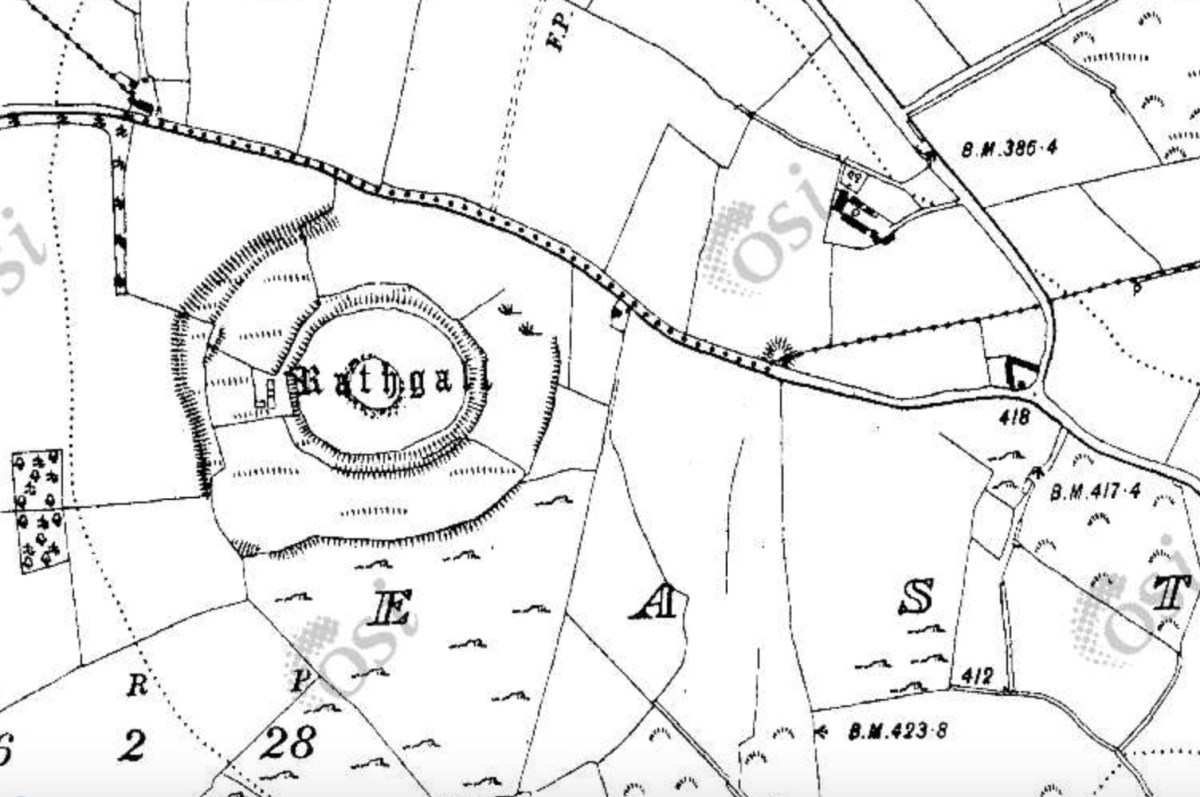

Rathgall from the early OS map. The importance of the site was realised and kept in use by successive generations.

Our knowledge of the societies that centred their life on settlements such as these in Ireland is sparse: here, and elsewhere, we are left with evidence of their stone structures (which will outlast us) but also intriguing finds – the following quotations summarize some of Professor Rafferty’s work here (courtesy of Rath Community Group and The Heritage Council):

1969 – 1971 . . . It took over 3 years to dig out the entire 15 metre wide section of the inner circle. Within an hour of starting work, he [Professor Rafferty] had located pottery pieces. Over 10,000 finds were from the inner circle; glass objects, clay moulds, stone and gold objects. Post holes indicate that there was a small house-like structure within the circle. The ditches were filled in with black material among the stones. An oval pit was discovered near the centre of the house. It had a carefully placed large boulder on top of black material almost covering the pit. The pit had been back filled in with yellow clay around the boulder. When the black clay was taken out, they found a small gold-plated copper ring, 1 cm wide approx, embedded in burnt baby’s bones. They came to the conclusion that this was a ritual burial pit . . .

1972 – 1973 . . . They moved to the southern slope of outside of the inner circle and were getting 400 finds per day. Prof Rafferty got down to prehistoric levels after 1 foot in some places. This area was “jampacked with artefacts, glass, gold, animal bones, pottery and basket remains.” Rabbits had done a lot of damage and stones were removed by people over the years. They found hundreds of clay mould fragments embedded in a black clay-like substance. Clay moulds are always broken when found as they could only be used once. The moulds were made for swords or whatever was needed: copper was poured in and in order to get out the sword etc, the mould had to be broken. He found a smaller crucible with traces of lead in it, parts of blades of swords or rapiers, spearheads, cauldron legs but not the cauldron . . .

1974 . . . In Bronze age times people were buried crouched down in a foetal position and put in a clay pot. The remains of a female and child were discovered in such a clay pot at Rathgall, buried in a pit underneath large slab stones. Eighty eight glass beads were uncovered, which is the largest quantity found in any Bronze Age site in Ireland. These beads are 1 – 3 cm wide, mostly circular in shape, blue-green in colour and with a hole in them. This collection is unprecedented in the late Bronze Age of Ireland and is also one of the largest from a single site as yet discovered in Western Europe (Rafferty and Henderson 1987). Prof Rafferty found a 2cm twisted gold cylinder with its ends finely hammered and a dark green glass bead mounted in the middle, 2 – 3cm wide. Tiny delicate loops of gold were attached to each end. This is an object of great beauty and advanced technological expertise. He also found a metal disc with mercury gilding on it. Mercury gilding was used to stick gold to bronze. He got this piece analysed by the British museum and the piece was dated back to 1000 BC. Before it was analysed, the Irish professionals were uninclined to believe that this came from Ireland as nowhere in the world had mercury gilding been found that dated back further than 400 BC. Prof Rafferty felt that this emphasised the exceptional importance of the Rathgall site . . .

While visiting this site I was reminded of an adventure we had last summer in Northern Ireland. You’ll find it here. There we discovered The Giant’s Ring: that earthwork struck us as ‘gigantic’. But it only occupies an area of 2.8 hectares. Our latest exploration is over 7 hectares! That makes it Cyclopean, surely! While this Co Wicklow site has been examined by archaeologists, we certainly don’t yet have all the answers as to why it existed, nor do we know everything we would like to about those who built it. We just can’t help expressing a sense of wonder at this – and other – artefacts which have made their marks on our landscapes. We are grateful to those who have explored and labelled these sites, and also to those who make sure they are conserved for our future generations, who might find more answers than we do as to their origins.