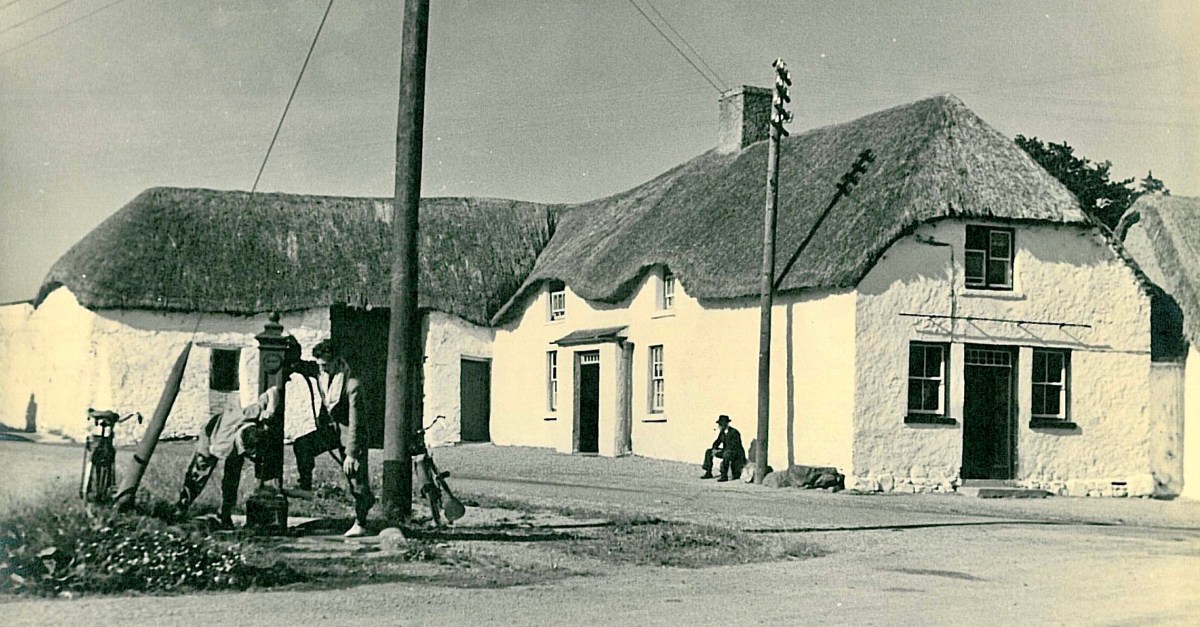

The traditional Irish village: Lusk, Co Dublin, in 1954 (photo from ESB Archives). Thatched buildings, the village pump, bicycles: a man sitting on the stone smoking his pipe. The intrusions are the poles and the overhead lines bringing the modern world into rural Ireland. Lusk was connected to the new grid close to the beginning of a project that spread out from the major conurbations from the late 1920s, taking some fifty years to embrace the whole state.

Rural Electrification arrives in Dromiskin, Co Louth, in 1949. Cork Electric Supply Co Ltd was in operation in Cork City before 1927. It supplied 4,225 homes and businesses in 1929, rising to 5,198 by March 1930, before being acquired by ESB in April 1930. Close neighbouring communities began to receive connections from 1930 onwards; Skibbereen and Bantry waited until 1937, while Schull and Ballydehob were without until works crept into furthest West Cork in 1952.

Above – family Life in 1950s rural Ireland (photo by Robert Cresswell). When I was a boy in 1950s England, I was probably fortunate to live in a house where electricity had been connected: my parents were quite progressive in that respect. I well remember the brown bakelite switches and plugs (two sizes: small and large). However, I often visited my Granma who lived in a house without any of it. It was a bit like the one above (which is in Kinvara). Gas globes hung from the ceilings: they had to be lit with tapers while pulling down on a lever. Cooking and heating came from a black coal range, and there was one cold tap in the scullery. There was no bathroom or shower, only a toilet outside in a shed. But there was a large wireless set – just like the one shown above. It was powered by an ‘accumulator’ which had to be taken to the shop up the road to be refilled with acid every few weeks. My Granma lived and died without ‘electrics’.

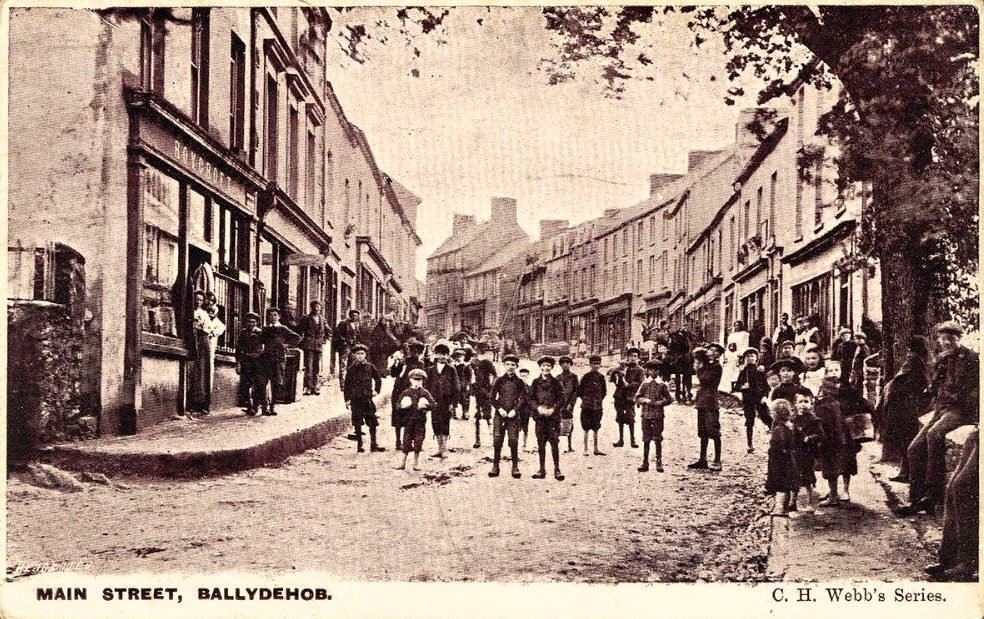

Above – Ballydehob before electrification. The ESB Archives are alive with colourful descriptions of the Rural Electrification works arriving here and in neighbour Schull. Reports from the on-site engineers are droll . . .

Schull Rural Area, April 1952 . . . Mr O’Driscoll opens his post-construction report in almost poetic terms and then to show that he is not bound to one form of art, proceeds to give us a word picture of the terrain in Schull, which is even more realistic than the deepest purples that Paul Henry ever used. We gather that pegging was, at times, a highly arduous and dangerous task and it would appear that among the wonders of the modern world, the greatest (in the view of the pegging team), was how this Area was ever selected for electrification . . .

ESB Archives

‘Pegging’ is a term in common use in the ESB Archives. It refers to the art of raising poles and stringing them with wires across the country. Evidently, the ‘landed gentry’ unkindly described them as “those beastly sticks”. Over 1 million poles were erected eventually, with 78,754km of wire used and a total of 2,280lbs of gelignite consumed during construction. The overall cost was some £36m (equivalent to €1.5bn today).

. . . We had very few wayleave difficulties. Sometimes an argument would develop with a local farmer whether the patch of grass where we put a peg was a field or not. If he convinced us it was a field, which he usually did by showing us the welts on his hand, we shifted the peg. It would seem too much like taking the bread from the mouth of a child to destroy his farm and livelihood by one pole . . .

ESB ARCHIVES

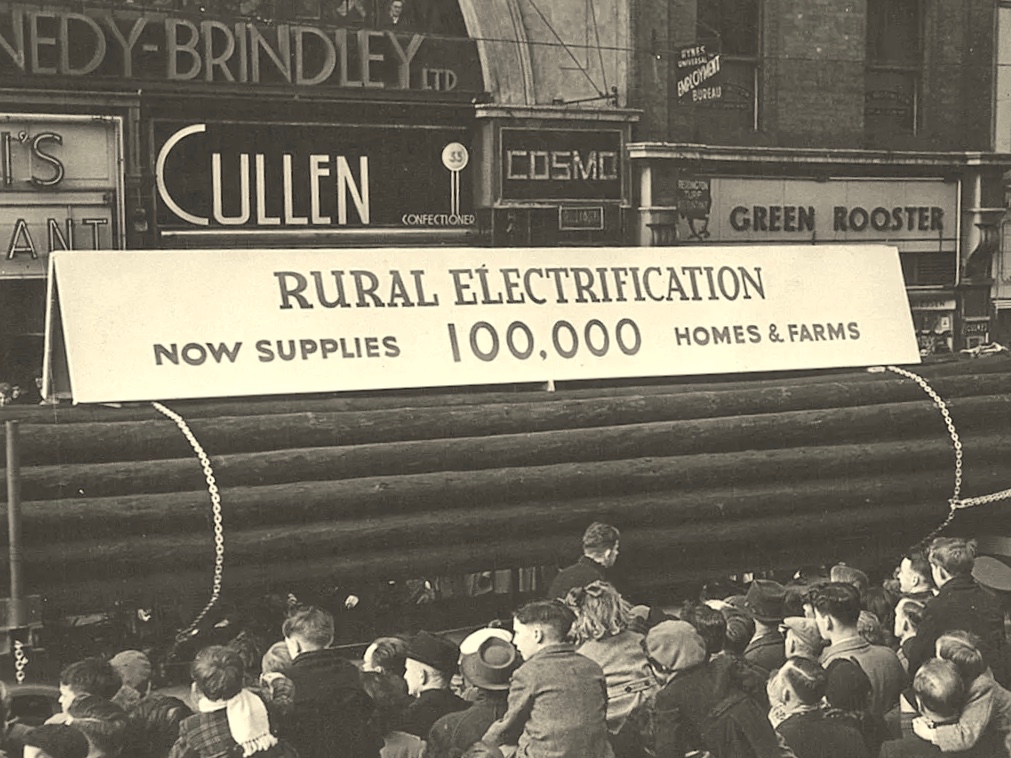

Above – Celebrations came with the connection of the 100,000th premises in 1954. Now we return to our own West Cork:

. . . It is interesting to note, and perhaps might be taken as a headline, that the early switch-in of the villages of Schull and Ballydehob (1952) had an excellent reaction on the more outlying areas and could not be denuded of all credit for the extra consumers eventually connected . . . There was an amusing revival of an ancient rivalry between the two villages. Ballydehob, looking with pride at their 100kVA transformer, were inclined to be scornful of Schull where a 50kVA transformer was erected; but the Schull people not to be out-done, countered by pointing out that there were many more poles in their “Town” than in Ballydehob “Village”. . . Only 8 houses remained to be wired when the gang left the area, 3 of these were parochial property and 4 were under the control of the Board of Works . . .

ESB ARCHIVes

The mention of “parochial property” in the paragraph above – from the ESB Archives – is of significance. The term would be applied to churches and schools, certainly. As outlined in last week’s post, Seán Keating was scornful of his view of the clergy position on Electrification: his Night’s Candles painting shows the priest still reading by the light of a candle while the world moves on around him. We can find differing views on the attitude of the Church.

. . . Throughout the length and breadth of Ireland politicians of all political shades lobbied the ESB for their area to be electrified. It wasn’t just politicians who tried to exert their influence: in July 1957, the parish priest of Ballycroy, County Mayo, wrote to the Rural Electrification Office. He said that his parishioners were anxious and that they believed he could influence decisions at the Dublin head office. “Sometimes people get an idea that the PP isn’t taking any interest in these matters. I need not add that I have a very deep enthusiasm for the light coming to Ballycroy” . . .

The Irish Story.com

Above – celebration in Dublin St Patrick’s Day Parade 1954. Here in Ballydehob I was pleased to hear some reminiscence from retired schoolmaster Noel Coakley pertaining to the ‘parochial property’ which remained to be wired when the gangs left the area:

. . . Having had the luxury of the electric light when growing up in Bantry town in the 1940s and 50s, rural electrification was a subject of which I was blissfully unaware until my first teaching post, 60 years ago next month in Tragumna National School near Skibbereen. Though the building was wired for electricity and rural electrification had already arrived in the area, the school wasn’t connected to the grid. On checking the reason, the reply I received from the then School Manager, the local Parish Priest, was, ‘Why would a school need electricity?’ End of the matter! Indeed, I should have known better because my own alma mater, Bantry Boys’ NS which was on the Hospital Road, wasn’t even wired for electricity. In fact, it wasn’t connected until the autumn of 1970 during the 2 year experiment, 1969-71, on having Summer Time all year round. Back teaching in Bantry by then, teachers and pupils had to endure almost pitch dark classrooms for the first year of the trial. Coming to Ballydehob in February 1971 was going from darkness into light because the school here could even boast of having electric sockets into which we could plug new fangled machines like tape recorders, while Bantry Boys’ had only being upgraded to two 100w single bulbs per classroom. Regarding Rural Electrification in Ballydehob, I think the village was connected around 1954. I do recall that the area around the townland of Knockroe, bordered between Bantry Road and Skibbereen Road, didn’t get connected until the 1970s because the majority of residents refused connection when the rest of the district was being electrified . . .

Noel Coakley, Ballydehob – personal communication

Above – a network of ‘pegs’ crossing the north side of the Mizen today.

Once again, I am grateful to Michael Barry for pointing me in the direction of some of this information, and for switching on the lights for me in respect of the extensive ESB Archives. I also appreciate the contributions of Noel Coakley and Eugene McSweeney, Ballydehob. Are there any other stories out there? More to follow next week!