St Brigid, according to some accounts, died in 524. Therefore, we are celebrating this year the 1500th anniversary of her death. Once again, I have gone back to primary sources for incidents from her life and am illustrating them with stained glass images. This year I have added as a source the famous Canon O’Hanlon’s Life, from his Lives of the Irish Saints Series, Vol 2, a work of overwhelming erudition.

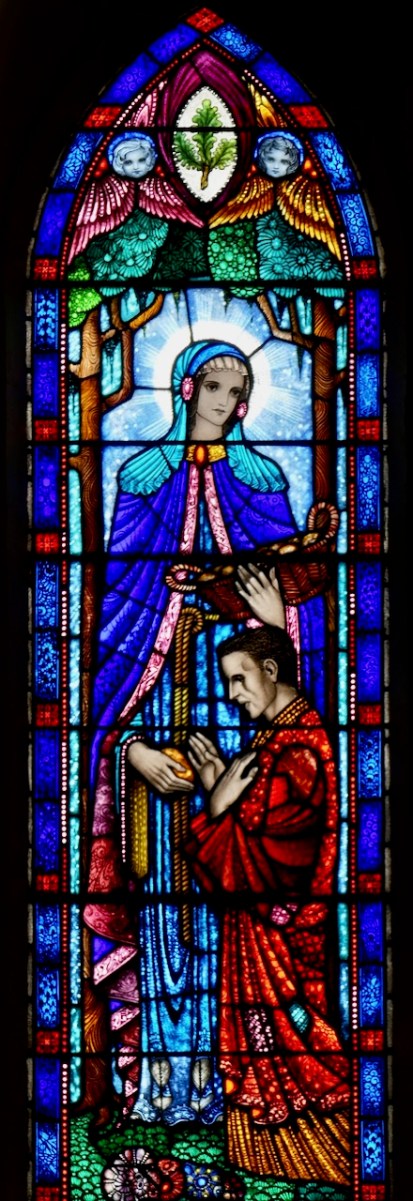

The Patrick and Brigid window in Meath Hill, by George Walsh. I love that Brigid has precedence over Patrick in this enormous cruciform window

If you haven’t already done so, now is a good time to go back and read my 2022 post, St Brigid: Dove Among Birds, Vine Among Trees, Sun Among Stars and my 2023 post, Brigid: A Bishop in All But Name. In them, I explain what the original sources for the Life of Brigid are. They all contain similar accounts and may be ultimately based on a single source – the Life of St Brigid by St Ultán – and are laid out as a series of miracles that lead us from her birth to her death.

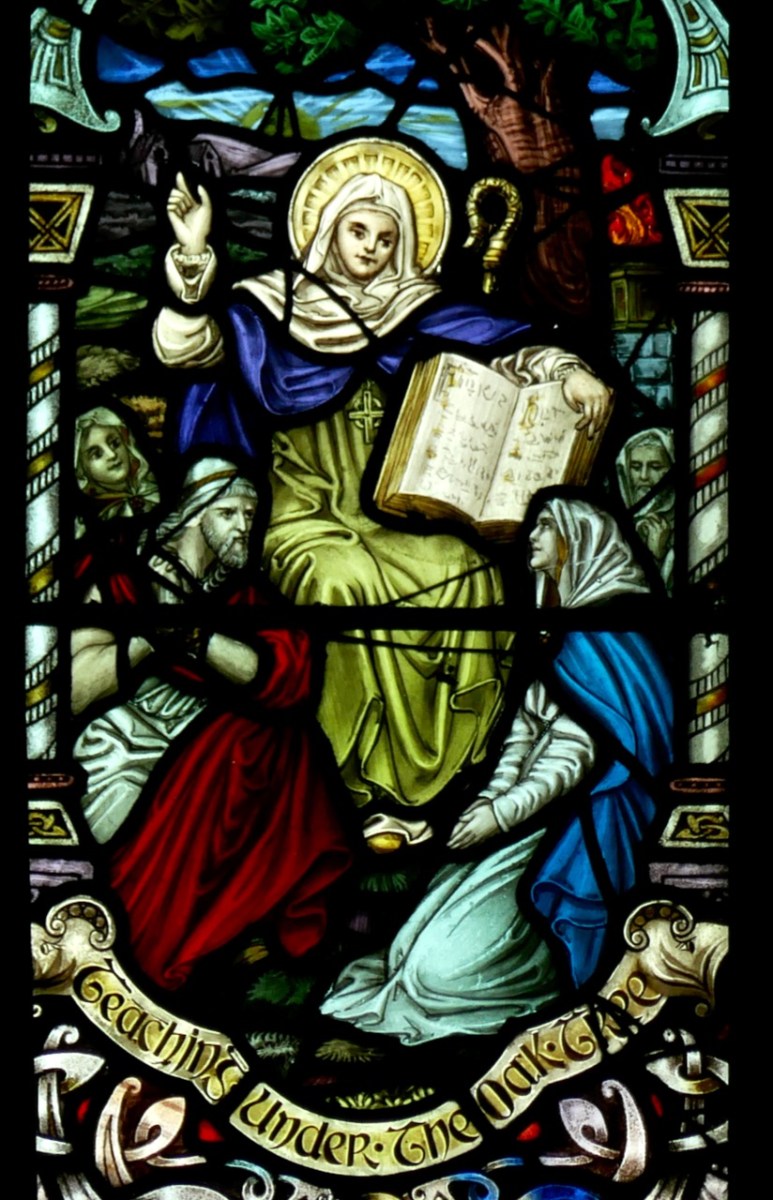

This is a detail from a window in Ballynahown, Co Westmeath, and is probably by Watson of Youghal. I like the clever way the oak leaves are used as frame and background

Many more miracles, legends, myths and stories accreted to her cult over the centuries. A good example of such a story is the one where she makes a cross from rushes – that one is nowhere to be found in the original Lives, but is an integral part of the folklore surrounding her, and therefore almost invariably found in her iconography.

This is a photo by Frank Fullard, used with permission and thanks. It is a simple treatment of St Brigid from Kilmaine, Co Mayo

She is associated with many places and numerous holy wells – just take a look at all the St Brigid’s wells Amanda has documented in Cork and Kerry. But of course it is Kildare that rightly claims her. Kildare (Cill Dara – the Church in the Oak Wood) is where she built her church and established her city. It is the origin of three of the attributes we see in many windows – a church, oak leaves and a lamp. (For the story about the Bishop’s Crozier, see the previous posts.)

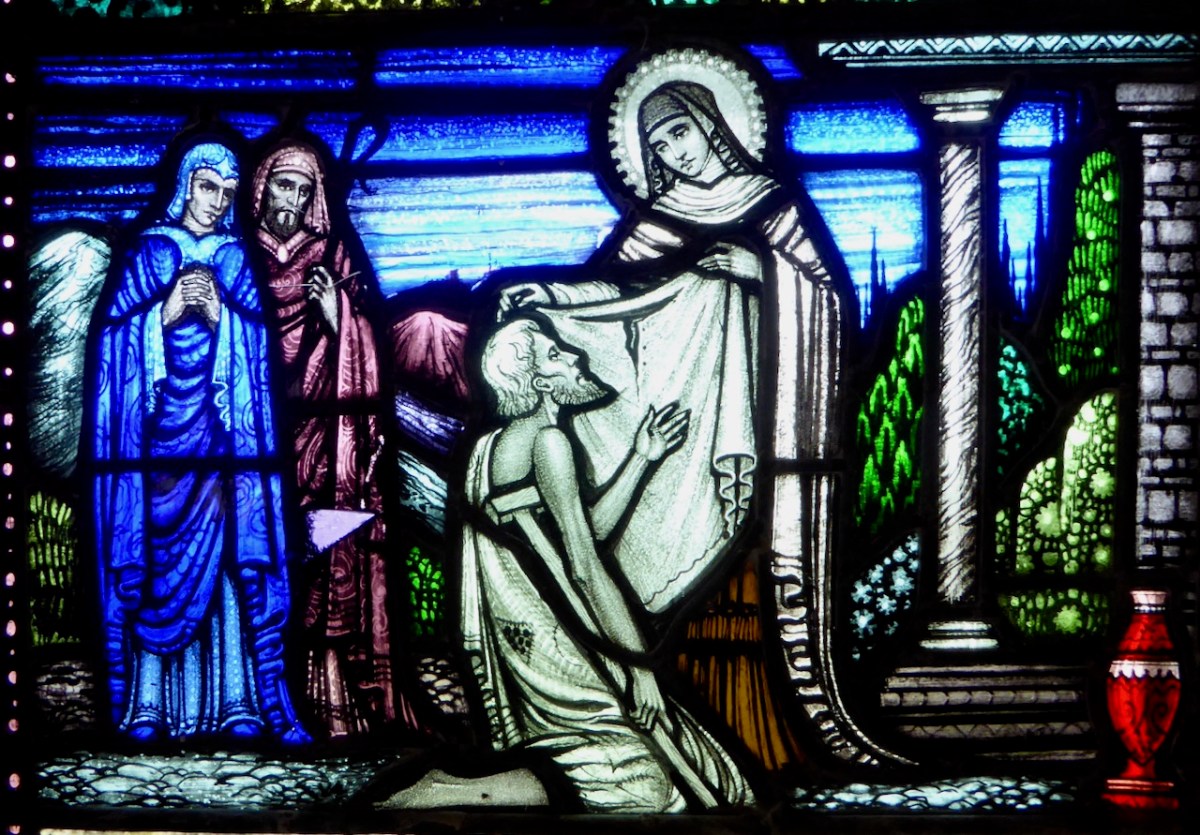

Detail from the Brigid Window in Carrickmacross – she’s consulting with her architects

The Book of Lismore has this story about building the church:

Brigit went to Bishop Mel, that he might come and mark out her city for her. When they came thereafter to the place in which Kildare stands to-day, that was the time that Ailill, son of Dunlang, chanced to be coming, with a hundred horseloads of peeled rods, over the midst of Kildare. Then maidens came from Brigit to ask for some of the rods, and refusal was given to them. The horses were (straightway) struck down under their horseloads to the ground. Then stakes and wattles were taken from them, and they arose not until Ailill had offered the hundred horseloads to Brigit. And therewith was built Saint Brigit’s great house in Kildare, and it is Ailill that fed the wrights and paid them their wages. So Brigit left (as a blessing) that the kingship of Leinster should be till doomsday from Ailill, son of Dunlang.

Detail from the Brigid window in Sneem, Co Kerry, by Watson of Youghal

It was a large establishment. O’Hanlon says:

We are informed, that her Rule was followed, for a long time, by the greatest part of those monasteries, belonging to sacred virgins in Ireland; nearly all of these acknowledging our saint as their mother and mistress, and the monastery of Kildare as the headquarters of their Order. Moreover, Cogitosus informs us, in his prologue to her life, that not only did she rule nuns, but also a large community of men, who lived in a separate monastery. This obliged the saint to call to her aid, and from out his solitude, the holy bishop, S. Conlaeth, to be the director and spiritual father of her religious; and, at the same time, to be bishop of the city. The church at Kildare, to suit the necessities of the double monastery and to accommodate the laity, was divided by partitions into three distinct parts. One of these was reserved for the monks; one for the nuns; while a third compartment was intended to suit the requirements of the laity.

Harry Clarke’s 1924 window in Cloughjordan is of the Ascension with Irish Saints – this is a young St Brigid, holding her church

And what about the lamp? This is interesting, as its first appearance was not in any of the lives but in the writings of the notorious Giraldus Cambrensis, Gerald of Wales. He will get a post of his own in due course, but for the moment, if you are not familiar with him, there’s a delightful sketch of him and his writings about Ireland in the 12th century here.

Brigid window in Kilgarvan, Co Kerry, by Earley and Co

Here is his story about the sacred fire, now usually rendered as a lamp, as faithfully related by O’Hanlon:

Speaking of Kildare city, in Leinster, which had become so renowned, owing to its connexion with our glorious abbess, Giraldus Cambrensis says, that foremost, among many miraculous things worthy of record, was St. Brigid’s inextinguishable fire. Not, that this fire itself was incapable of being extinguished, did it obtain any such name, but, because nuns and holy women had so carefully and sedulously supplied fuel to feed its flames, that from St. Brigid’s time to the twelfth century, when he wrote, it remained perpetually burning through a long lapse of years. What was still more remarkable, notwithstanding great heaps of wood, that must have been piled upon it, during such a prolonged interval, the ashes of this fire never increased.

Another detail from the Watson window in Sneem

What is furthermore remarkable, from the time of St. Brigid and after her death until the twelfth century, an even number, including twenty nuns, and the abbess, had remained in Kildare nunnery. Each of these religious, in rotation, nightly watched this inextinguishable fire. On the twentieth night, having placed wood on its embers, the last nun said:” O Brigid, guard thy fires, for this night the duty devolves on thyself.” Then the nun left that pyre, but although the wood might have been all consumed before morning, yet the coals remained alive and inextinguishable. A circular hedge of shrubs or thorns surrounded it, and no male person dare presume to enter within that sacred enclosure, lest he might provoke Divine vengeance, as had been experienced by a certain rash man, who ventured to transgress this ordinance. Women only were allowed to tend that fire. Even these attendants were not permitted to blow it with their breath; but, they used boughs of trees as fans for this purpose.

This is the predella from the Brigid window in Moone, by the Harry Clarke Studios (see blow for the main panel)

All of the Lives and O’Hanlon’s account tell of Brigid’s many miracles in providing food and clothing for the poor, in healing sicknesses, in turning the hearts of evildoers to God, in freeing slaves, and in punishing those who are selfish or cruel.

Brigid and the Beggar, by William Dowling, Gorey C of I

However, the story I like best perhaps is this one from the Vita Prima:

In the same place also when saint Brigit was staying as a guest, a married man came with a request that saint Brigit should bless some water for him to sprinkle his wife with, for the wife actually hated the husband. So Brigit blessed some water and his house and food and drink and bed were sprinkled while his wife was away. And from that day on the wife loved her husband with a passionate love as long as she lived.

She may have been a nun, but she obviously served up a good love potion when the situation required it. This story is not only repeated in the Book of Lismore, but embellished, thus:

When he had done thus, the wife gave exceeding great love to him, so that she could not keep apart from him, even on one side of the house ; but she was always at one of his hands. He went one day on a journey and left the wife asleep. When the woman awoke she rose up lightly and went after the husband, and saw him afar from her, with an arm of the sea between them. She cried out to her husband and said that she would go into the sea unless he came to her.

The aged St Brigid by George Stephen Walsh, in Ballintubber Abbey – another image generously loaned by Frank Fullard

My final point for this post about St Brigid is the matter of where she is buried. Most authorities give this as Downpatrick, where she is laid to rest alongside Patrick and Columcille. However, a medieval legend grew that she went to Glastonbury in old age and died there. That is why she is venerated in Britain as well as in Ireland – the top photograph in this post is from the St Brigid window in Exeter Cathedral. Here’s the full window, in which she is flanked, for some reason, by St Luke and St John busily writing their gospels.

Here is another British window, this one designed by Nuttgens in 1952 for St Etheldreda’s Church in London. (Used with thanks under the Creative Commons License – original is here.) It’s a particularly good narrative window, showing the building of her church under the Oak Tree, her crozier, and two cows – there are many stories of milk and cows in the Lives.

But O’Hanlon is having none of the Glastonbury story.

We cannot receive as duly authenticated, or even as probable, several assertions of mediaeval and more recent writers, who have treated concerning this illustrious virgin. It has been stated, that about the year 488, Saint Brigid left Ireland, and proceeded towards Glastonbury. There, it is said, she remained, until advanced in years, on an island, and convenient to the monastery in that place. Whether she died there or returned to Ireland is doubted. But, it seems probable enough, such a tradition had its origin, owing to this circumstance, that a different St. Brigid, called of Inis-bridge, or of Bride’s Island, had been the person really meant. She lived many years on a small island, near Glastonbury, called Brigidae Insula i.e., Brigid’s Bridge. This latter St. Brigid is said to have been buried, at Glastonbury.

This Brigid window is in Moone, Co Kildare from the Harry Clarke Studios. It features, as do many Brigid windows I have seen, a deer, but I can find no mention of a deer in any of the Lives. Perhaps one of our readers knows where the deer icon comes from?

I will finish with a quote from the Book of Lismore, which gives me the title for this post, and gives Brigid one of her most frequent soubriquets.

It is she that helpeth every one who is in a strait and in danger: it is she that abateth the pestilences: it is she that quelleth the anger and the storm of the sea. She is the prophetess of Christ she is the Queen of the South: she is the Mary of the Gael

I don’t know whose window this is – it’s from Ballybunion – but I love the composition

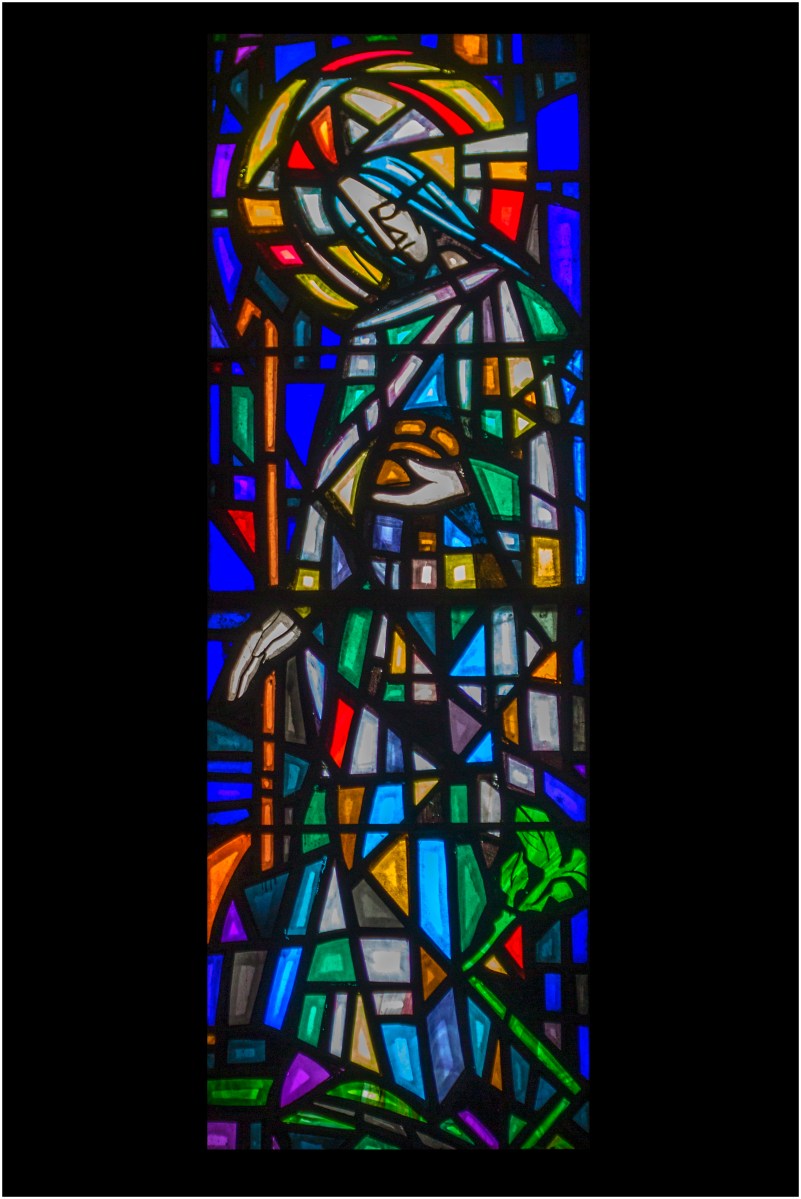

And a final image from Glynn, Co Wexford, because I love the pared-to-the-bone simplicity of this Richard King medallion..

Posts about St Brigid

Brigid: A Bishop in All But Name

St Brigid: Dove Among Birds, Vine Among Trees, Sun Among Stars