One of the ways in which Ireland of the Welcomes consistently sought to present an image of Ireland was through the lens of literature. As I said in a previous post on IOTW It showed us what others might find interesting about Ireland and therefore what we ourselves could be proud of. Ireland was so different then – but Ireland of the Welcomes was chronicling the emergence of who we are now. And all the best people wrote for the magazine, no doubt due to the canny and charismatic editor, Cork woman (and noted climber) Elizabeth Healy (below, from her obit).

In this next series of post, rather than going chronologically through the editions of 1972, I am going chronologically through the eras of Irish literature that were the subject of articles, beginning with the Bards! John Montague, the distinguished poet, (that’s him at the top) wrote a piece in July/August called Under Sorrow’s Sign, which I give in full below. There’s a wonderful interview with him in the Irish Film Institute Archives. He said he spent many hours discussing the poem with his great friend Sean Ó Riada. I met Montague during his tenure at UCC in the 70s and I remember the adulation with which we all viewed Ó Riada, as he strolled through campus, so this piece was a personal memory-trigger for me. Robert has written about Sean Ó Riada here.

The poem is by Gofraidh Fionn Ó Dálaigh, Chief Bard of Munster, who died in 1387. Becoming a bard was a long and rigorous process, which is described in a quote in the article:

Here is what is believed to be the remains of one of those O’Daly bardic schools, this one on the Sheep’s Head. Perhaps Gofraidh spent part of his apprenticeship here, among his O’Daly kin.

The poem itself was intended to be declaimed by a professional reciter (a reacaire), accompanied by a harpist, as illustrated in this famous woodcut of MacSweeney’s Feast from John Derricke’s 1581 Image of Ireland. It shows the harpist and the reciter in the act of entertaining the head table. Note they are marked with a D.

Under the woodcut is a legend. For D the text reads:

Both Barde and Harper, is preparde, which by their cunning art,

Doe strike and cheare up all the gestes with comfort at the harte

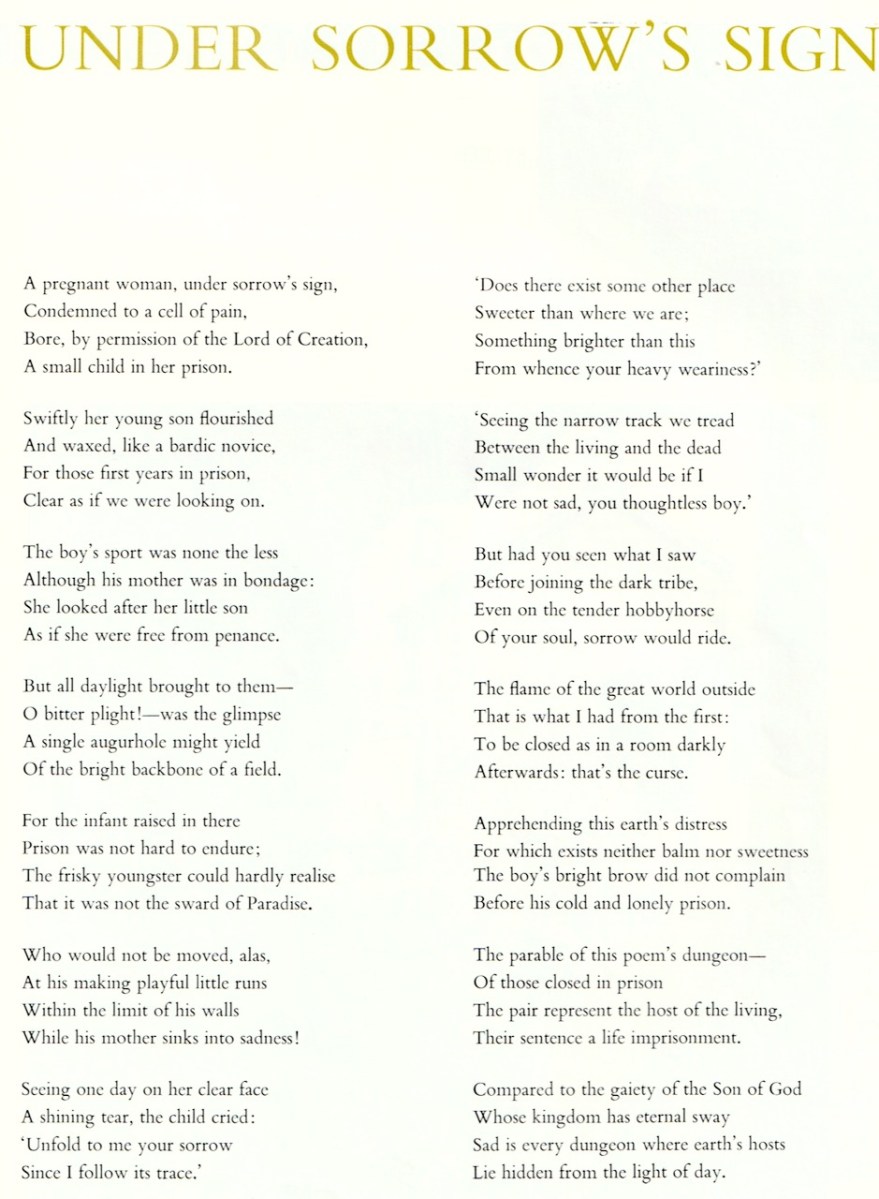

The poem is, according to Montague, a metaphor for earthly existence. He concludes his piece by saying: O Dalaigh was from Cork, where O Riada now lies buried: Across six centuries, its bleak but Christian vision speaks as an epitaph. Here now is Montague’s translation.

Thoroughly depressed now? I’ll try to be more cheerful in the rest of this series.