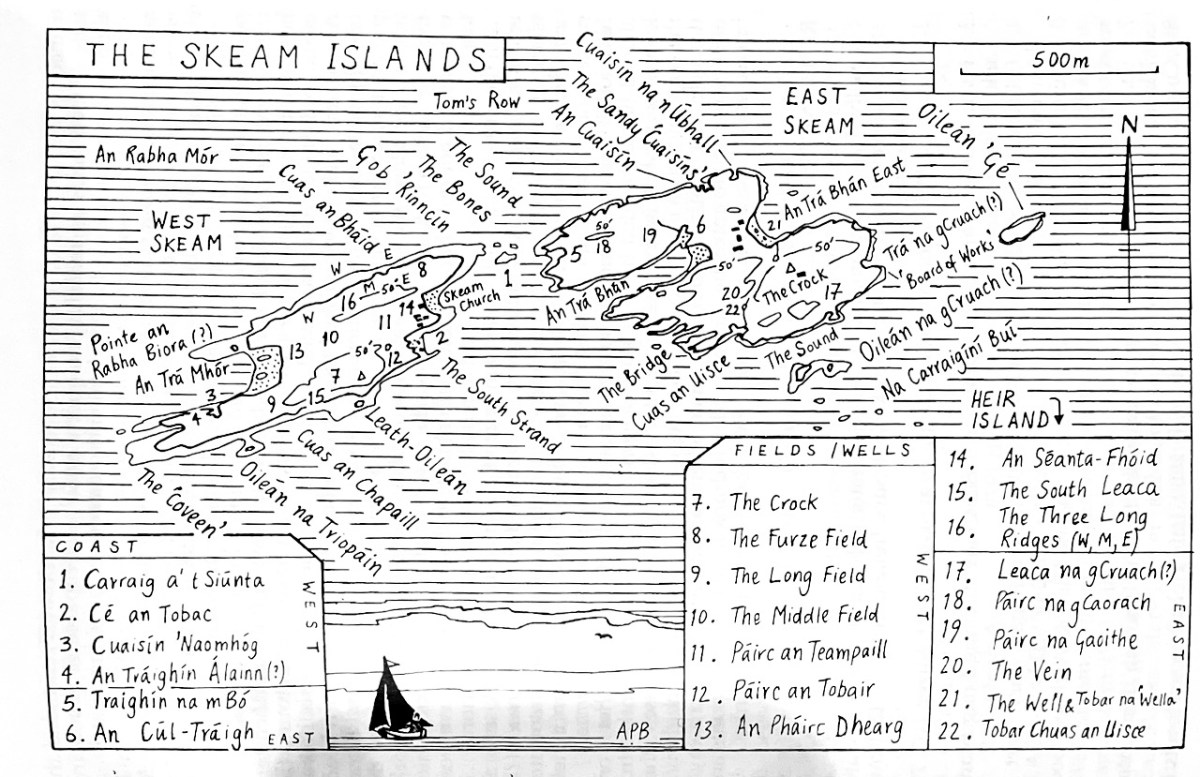

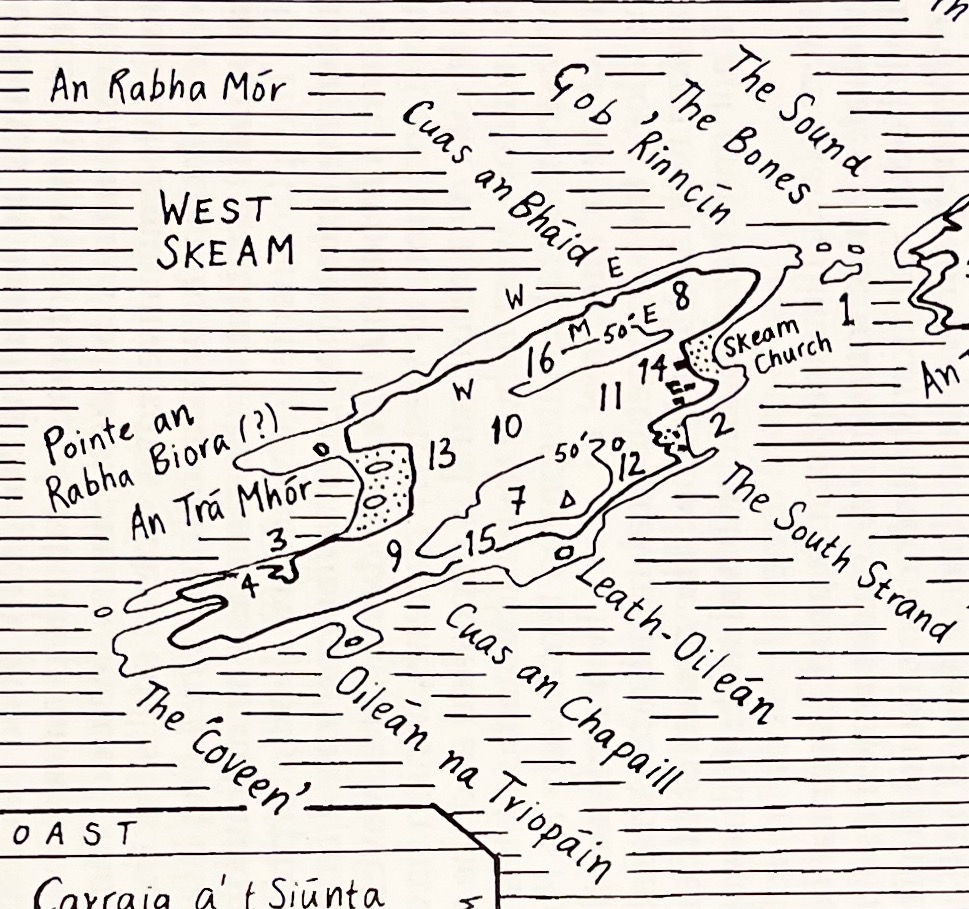

More about Hester and Joe’s story now, but let’s start off with another fantastic resource – Anthony Beese’s map of the island, published in the Mizen Journal in 2000*. What’s great about this map is that it was drawn up using local informants and so we have many of the places that Hester and Joe refer to.

For example, Gob ‘Rinncín. Joe tells us

The little field down by the point facing across to East schemes we called ‘Gobreenkeen’, because on a rough-ish day the waves coming in from the north and the waves coming in from the south, (especially if the tide was low), would meet and shoot up and twist and that would be the dance, the Gobreenkeen. It was there we got scallops in that kind of weather.

Rince (pronounced rinka) is the Irish word for dance, and gob means beak, or point. Therefore this word translates as the Point of the Little Dances. How lovely is that? I am imaging something like this…

Hester tells us about Oileán na Triopáin (illawn na tripawn)

We used to eat a green seaweed we called Triopán that grew plentifully on a rock called ‘Oilean na Triopáin’ on the south side of the island. It was cooked in milk and eaten with fresh cream.

I can’t find a translation for Triopáin – perhaps a reader might know what seaweed this is.

The quote The Sea dominated our lives is from Joe’s account, and here is a map showing the context of the islands. It is immediately obvious how exposed the Skeams are to the south west winds which are, in fact the prevailing winds around here.

Both Hester and Joe tell of times when it was impossible to leave the island, or get a doctor to a woman in labour. Joe tells us:

I think people who visit West Skeam don’t realise how high the waves are in a winter storm – big waves ride over the rocks, just missing the houses and pouring back down onto the Strand, quite a lot of water, not just spray. The problem was getting out or going anywhere in bad weather. It was always a worry for the people waiting for about to come back.

Hester says:

Because the island was situated among very rough sea currents, the weather was a big issue in our lives. Storms and high tides could come without notice. We had no weather forecasts but we did have our own signs from nature. Birds flying against the wind meant the wind was going to change for the better – the safest wind was the one blowing from the north east since it didn’t rage or raise the big waves. Bad weather was sure to come when seals were seen near the shore or the cattle were standing near the fence ‘tail for tail’ as if in a stall. Rain was on the way when the fish we had salted and dried for the winter or my father’s tobacco became wet. Very high tides meant a storm was approaching. The fishermen had many other signs that guided them to keep safe on the seas.

We had no landing pier so it was sometimes very hard to land in rough weather. A big swell would send tons of water up over the landing place and the men had to wait to drop off one or two between these breakers and let the boat go back out to safety until the next chance. They repeated this until everyone and the boat were safely ashore. They were great boatmen and understood where the danger was and how to deal with it. A stranger coming to the island would be drowned the first day.

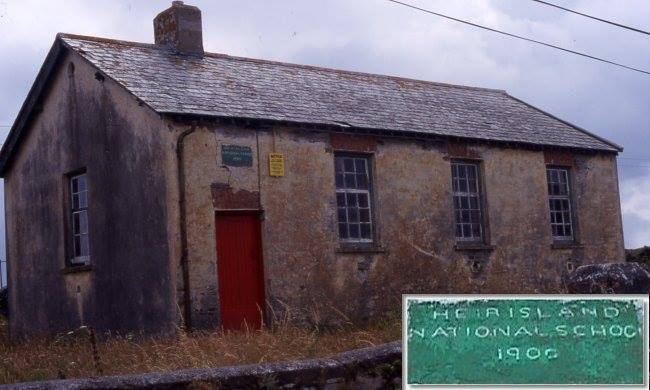

One of the most important effects of the sea on their lives involved attendance at school. The children all went to school on Heir Island, staying with their maternal grandmother in her small house, and having to wait their turn to attend until the older children no longer needed the beds. Thus, Joe didn’t start until he was 10.

Here is Hester’s story:

My sister Mae found school hard and when her Confirmation time came, the teacher said she did not know her catechism well enough to put her in the Confirmation class. The priest backed the teacher. At that time I was eight years of age and still waiting to start school but my grandmother did not have space for me until Mae was confirmed and could leave school. My mother decided she would fight this injustice. On the day of the Confirmation she brought Mae to the altar rails and put her in with the other children. She met the priest and told him she would talk with the Bishop. Her sister-in-law who taught in Lisheen school in the mainland (being a teacher meant power in those days) met the Bishop with her. They had a very fruitful talk with him and he understood the situation. The Confirmation class was always examined by a priest who came with the bishop on the day. Mae was able to answer the few simple questions. The visiting priest called her aside and told her to come up with the other children to be confirmed. The Parish Priest and her teacher were raging. Poor Mae never forgot that day. She was so embarrassed. You would talk today about being bullied in school! My mother and her sister-in-law told that story while they lived.

Hester and Joe’s mother, Kate, had prepared them at home, teaching them to read and ‘do sums.’ Joe liked school at first and enjoyed meeting other children but he was very homesick. Here is his moving story.

On Friday evenings my parents would row or sail over to take one or two of us home. My grandmother never wanted us to go because there were always jobs to be done. Often on a Friday evening, especially in winter, we would stare across the water looking for a boat coming to take us home, and that was the highlight of the week. It would be a rowing boat in winter, because you could not manage a larger sailing boat. We would play in the fields, the four of us but never for long – we kept looking out across the water. I would sometimes imagine, just as it was getting dark, that I had seen a boat coming; sometimes it was not ours, but a boat going somewhere else, and my heart would sink and I would go away and cry.

That’s a traditional Heir Island boat, above – perhaps like the one Joe was longing to see. Both Hester and Joe say that when their uncle married there was no longer room at their grandmother’s house and so they would row to school when the weather permitted. Neither minded missing school and all the O’Regan children found great contentment in each other’s company.

Hester describes what happened after Christmas: When the feasting was over, we had to go back to Heir Island and school. It was so hard to leave home, we were lonely for weeks afterwards. Joe says: At home we never missed the company of other children. We would go upstairs to do homework or sit looking out the windows at the big waves coming over the rocks.

The school on Heir Island finally closed in 1976. By that time it was down to one student. Next time, more about daily life on the island.

* The Natural Environment and Placenames of the Skeam Islands by Anthony Beese. Mizen Journal, No 8, 2000