Cahergal is undoubtedly one of the finest examples of a stone ringfort or cashel in Ireland. What makes it outstanding is not the overall size of the enclosure or the height of the enclosing wall but the quality of the drystone masonry, the width of the entrance, the thickness of the wall and the well-planned and executed almost symmetrical stairs and terraces on the inner side of the wall.

Excavations at Cahergal, Co. Kerry:

A Venue for Royal Ceremony in Early Medieval Corcu Duibne

All quotes in this post are from the 2016 excavation report by Conleth Manning of National Monuments*. Con’s report deals with the 1986 brief excavation near the entrance, and his own 1990-1991 excavations inside the cashel. The excavations established a date for the fort – it was originally built between the mid 7th and the mid-9th centuries – as well as providing evidence for its status and uses. It also established the basis upon which most of the restoration work was done – although note I say ‘most.’ In the photo above you can clearly see the old and newer stonework.

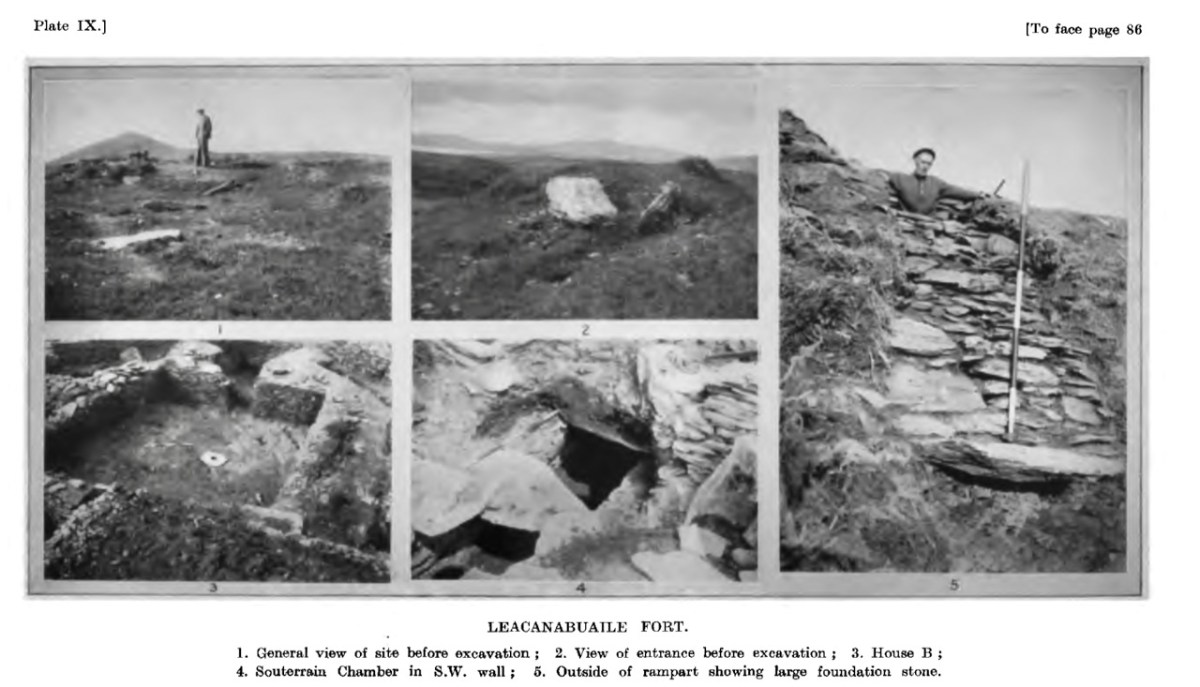

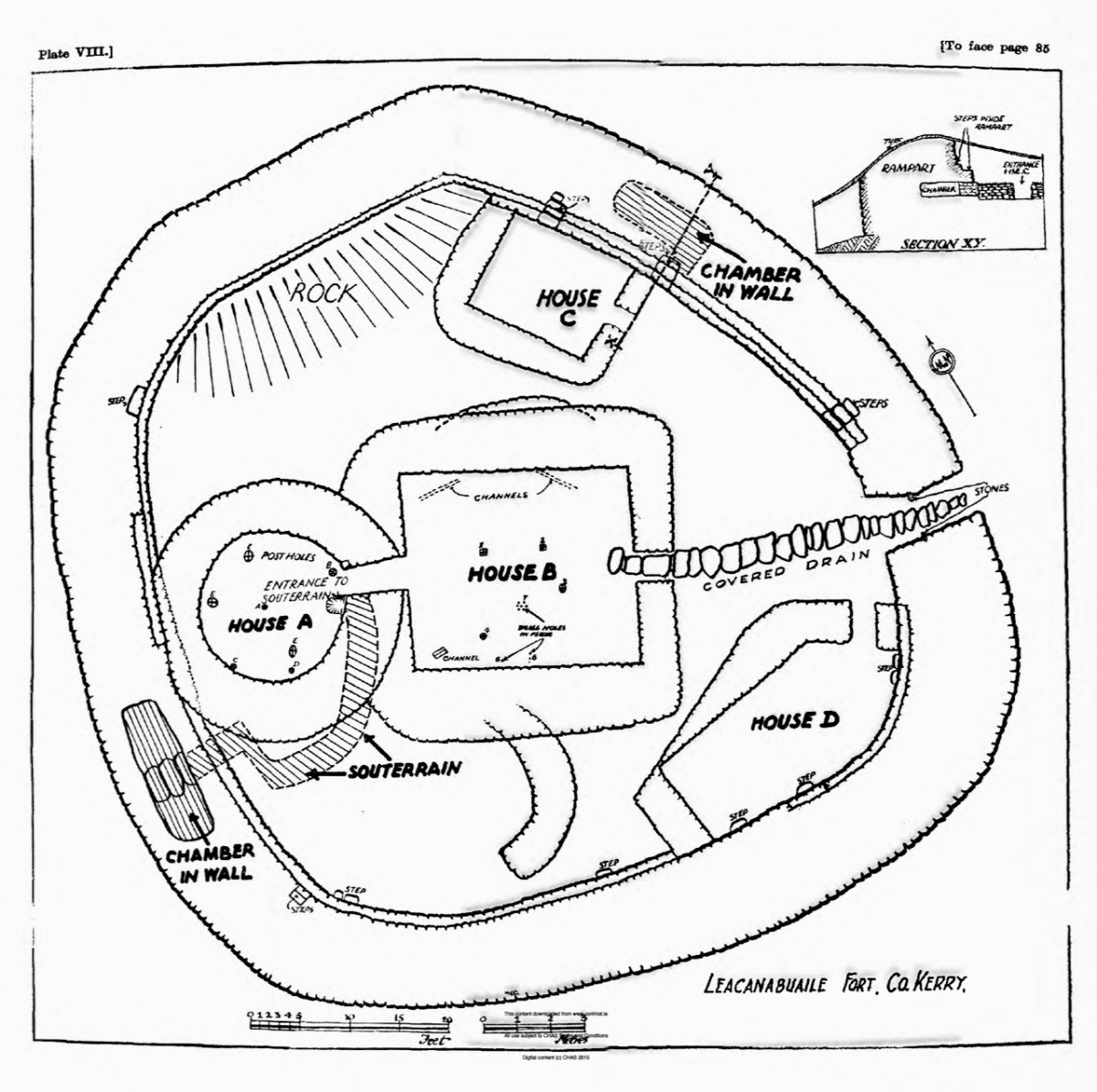

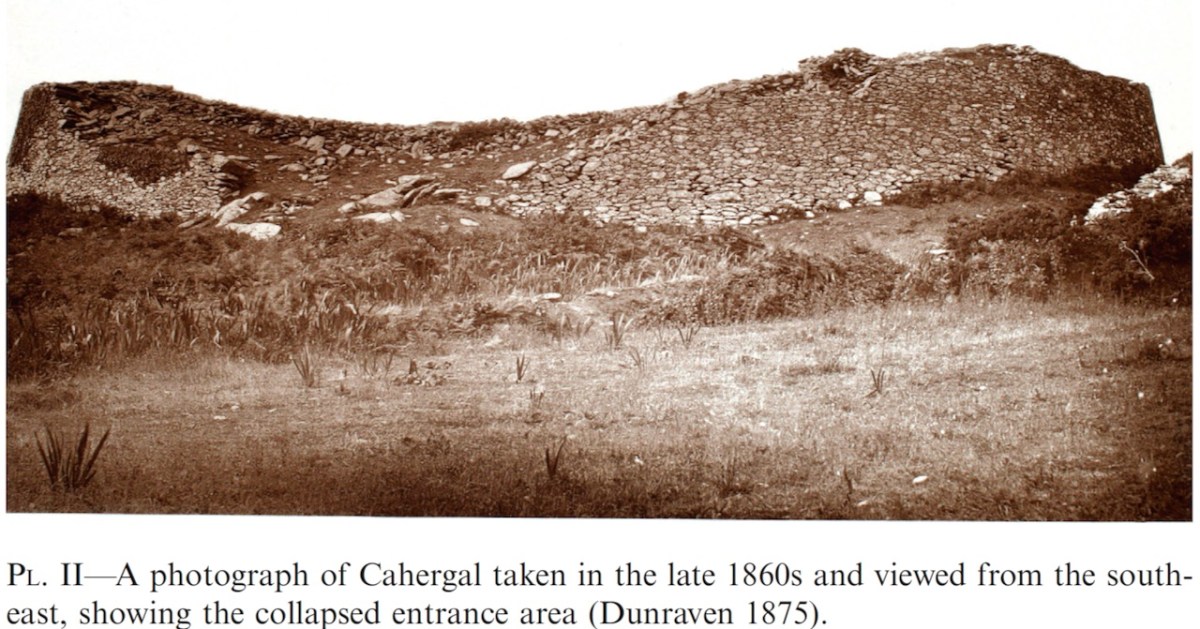

Like Leacanabuaile, this was a rather tumbledown ruin before excavation and restoration projects. All that incredible masonry work did not save it from the ravages of time, although the exceptionally high standards of building became clear as it was dug out from the jumbles of stone and grass that covered it.

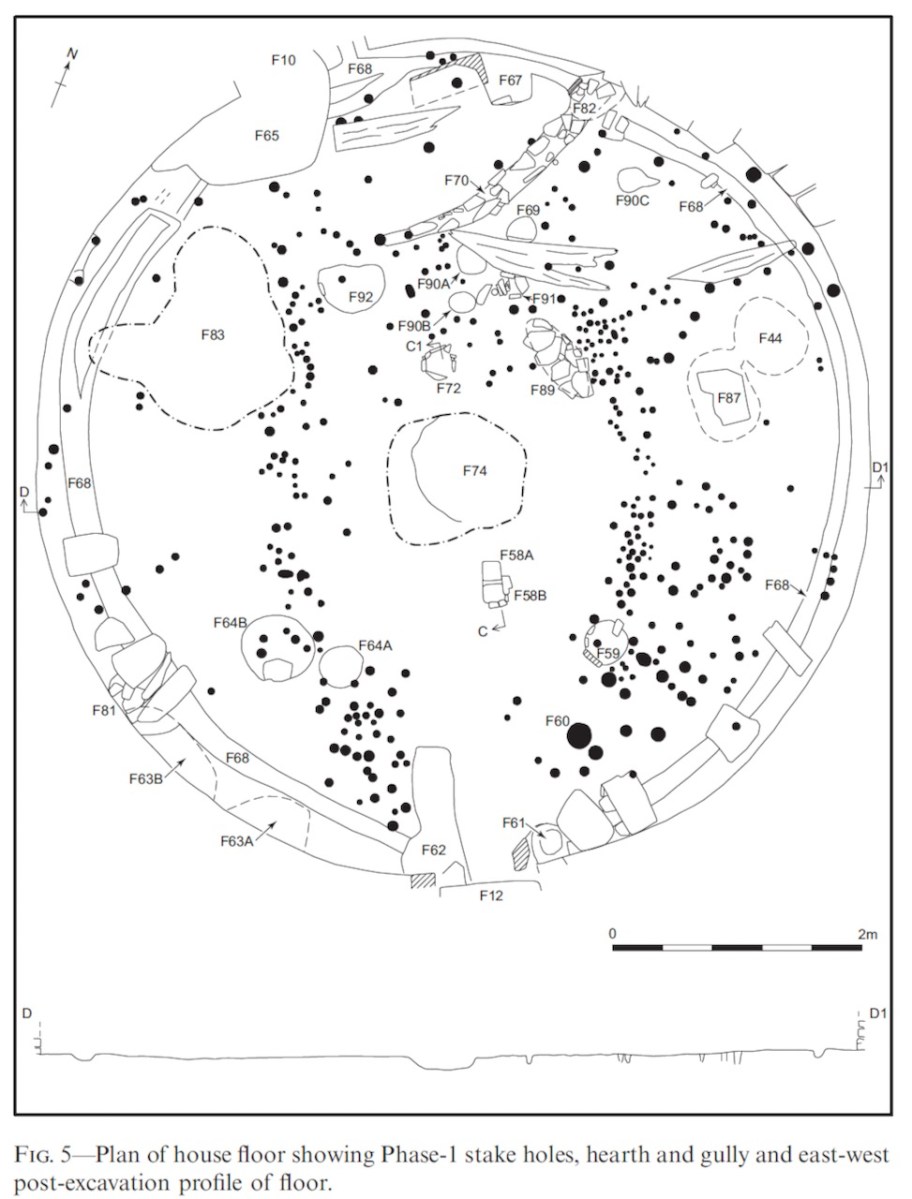

The initial stages of building included the walls, with its staircases, the entry passageway and the fine paving, as well as the round house in the interior.

The stairs and terraces on the inside of the walls are one of the striking features of this fort. There are two levels of terraces along most of its length, but in one area the stairs went up to three flights. The excavation report states, The third set of steps probably led to a wider viewing terrace, which was likely to have been flanked externally by a parapet wall.

After the excavations the OPW continued to work on the restoration of the fort and this finding was interpreted to mean that this section of the walls was much higher than other sections. This led to a decision to raise the top of the wall in this section, leading to the somewhat startling profile we see now. According to Con Manning this is a skewed interpretation by the OPW and it is highly unlikely that it reflects what the wall actually looked like.

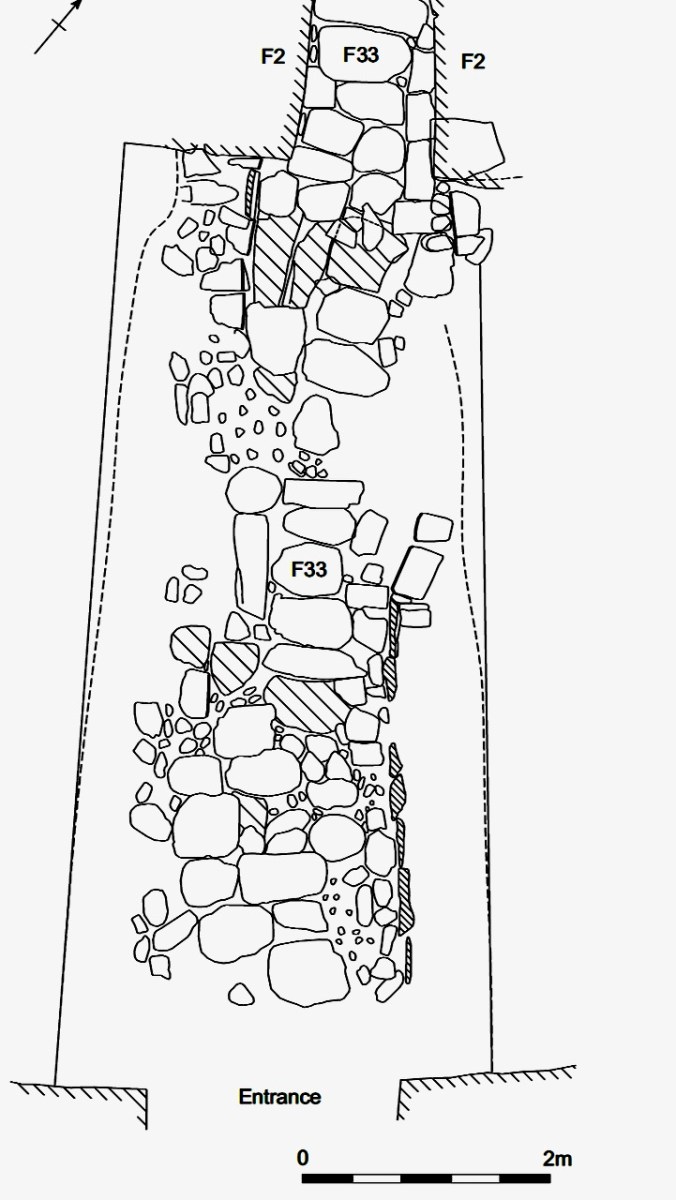

The entrance to the fort had completely collapsed but excavation revealed how deep it had been. A pair of upright jamb stones and fallen lintels were found, leading to the reconstruction as we see it today.

The house was circular and the amount of fallen stone inside led to the conclusion that the roof was originally made of stone, probably using a corbeling technique. If this was the case, this house is the largest round building known to support a stone roof, well known from church sites (such as Kilmalkeader) where the stone roofs are rectangular and steeply pitched.

A very finely laid-down pavement led from the fort entrance to the door of the house. The pavement was delineated at the side by edge-on kerb stones. The house originally had three doors, with the main one positioned across from the entrance to the fort, and accessed by walking along the pavement.

Internally, there was a central fireplace (Feature F74 in the pan below). Stake holes around this central feature were probably to support a beam or spits for cooking purposes. The fireplace itself showed that numerous fires had been burned in it. Other stake holes supported furniture for sitting or sleeping.

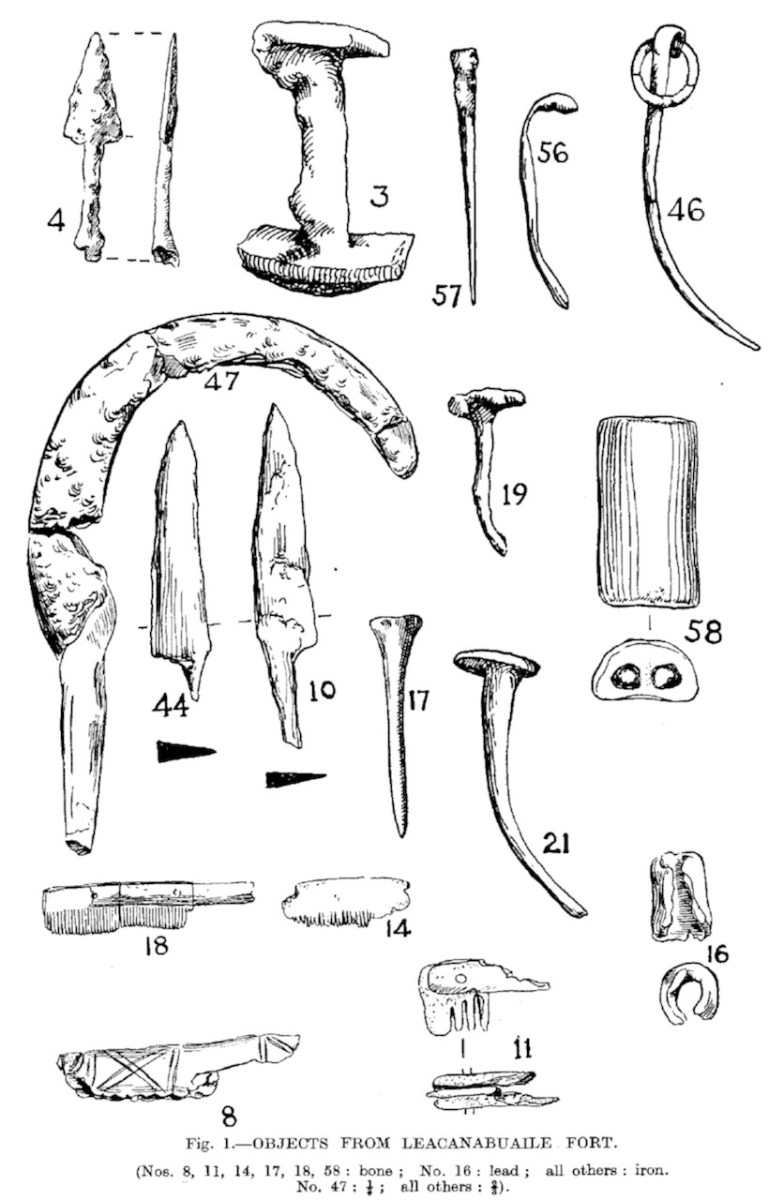

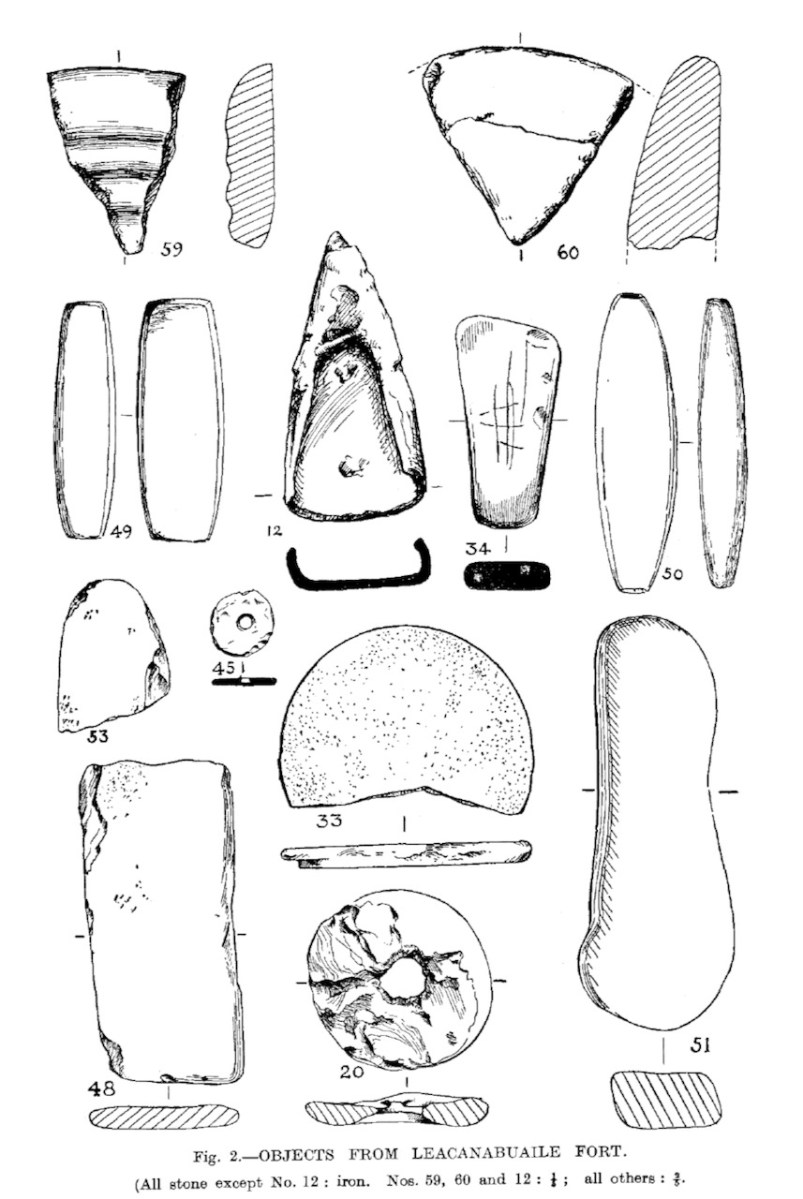

The strange thing about Cahergal is that the excavations yielded very few finds (compared to Leacanabuaile, for example) and what was found mainly dated to later periods of occupation. So – what was going on during the original period of occupation – mid 7th to mid 9th centuries? Manning speculates that this was actually a royal site, built to impress, to inspire awe, and perhaps to entertain. Ritual feasting would take place in the main house, which would be cleaned carefully afterwards and readied for the next great occasion.

The three doors might support its interpretation as a royal site. Manning says:

In each case the side entrance might have been for people of lower status, with the main entrance being reserved for kings, nobles and important guests. On the other hand one could regard the three doorways as symbolic, three being a magical number as in the triads, and in this case could symbolise the three divisions of Corcu Duibne. In the tale of Branwen daughter of Llyr, in the medieval Welsh Mabinogion, a royal hall with three doors is mentioned in the house of Gwales (Grassholm), where one door, facing Cornwall, was kept permanently closed with a taboo on opening it.

This interpretation of the function of the fort and house – designed to impress and to underscore the prestige of the builders – reflects the later castle-building of Irish chieftains. Here in Ivaha, for example, the O’Mahony clan built tall, overpowering castles to cement their control over the land and the sea around them. Cahergal is within sight of two other cashels – the Castles of Ivaha were often within sight of each other too. Annals tells us that the Taoiseach of the O’Mahony clan built a castle for each of his sons, or other members of his ‘derbfine’ – the family group from which the chief was chosen.

As if to confirm this possibility, Ballycarbery Castle, a 15th century tower house, lies within clear sight towards the coast. Was this a continuation of the same tradition by the same family – the Falveys? Manning concludes his report by stating:

This [high-status] phase ended with a burning of the internal features and subsequent, probably occasional, lower-status use of the house between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries. Iron forging took place here in the fourteenth century. After the eastern half of the stone roof collapsed and the structure was abandoned for some time, it was roughly rebuilt as a D-shaped structure probably in the fifteenth century.

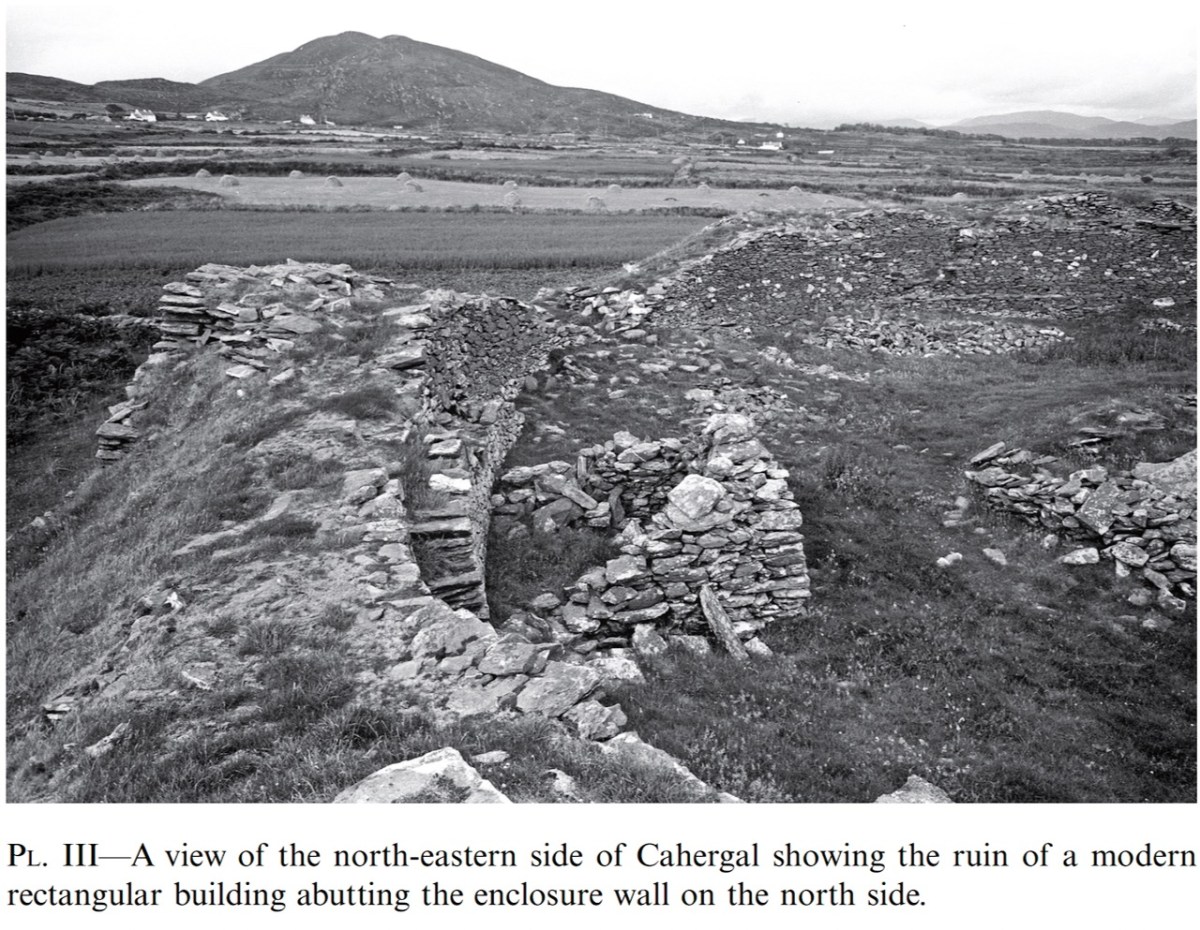

The last period of occupation was the modern period – the small building built against the wall in the photograph below was probably a sheep-pen noted by an antiquarian visitor.

The final fort we will talk about is Staigue – in many ways it’s the most spectacular (despite not being as well built as Cahergal) but it has not been excavated so less is actually known about it. Meanwhile, if you can’t get to Cahergal but want a Cahergal experience, visit the marvellous Voices from the Dawn – Howard works his 3D magic on this page.