I am fond of telling people (because I read it somewhere) that the Voyage of St Brendan the Navigator was a “medieval best seller.” But I have just acquired a book (above) that made me look more closely at that claim. And yes, it’s a true statement, and my book is part of a sprawling tradition of stories about our own beloved St Brendan, that were written across medieval Europe in many languages over several centuries.

This statue of Brendan dominates the town of Bantry. It’s by Ian and Imogen Stuart

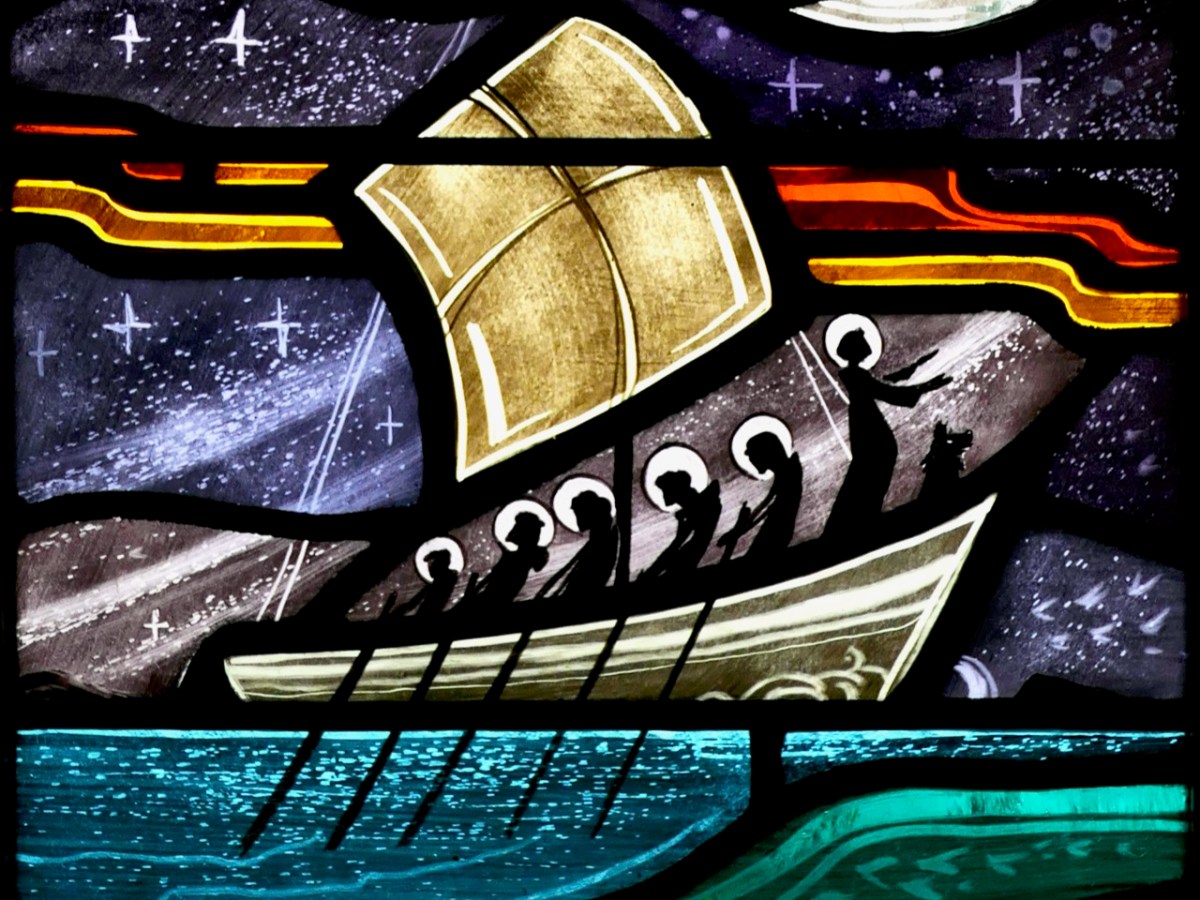

I’m mainly illustrating this post with images of St Brendan in stained glass or other art forms. Since he’s one of our favourite Irish saints here, this isn’t hard. But the next post will be illustrated by images from the book, St Brandanus: Der Irische Odysseus. This post is mainly background about St Brendan and his legendary journey.

Willy Earley’s Brendan, St Brendan’s College, Killarney

Brendan’s Navigatio is perhaps best understood as one manifestation of the deep well of mythology that many of our stories have come from. St Brendan sets out from Ireland with several companions (the number changes from version to version) and journeys over the sea for several years. Along the way he encounters wonderful islands, strange creatures, demons and whales, colonies of feathered men and beautiful women. Many miracles keep him and his companions alive and moving onwards towards the Land of Promise.

This window by Ethel Rhind of An Túr Gloine is also in St Brendan’s College in Killarney

This great Irish tradition of seafaring pilgrimage is called Immram and is part of a wider-world mythological treasury that includes Sinbad the Sailor and Odysseus, as well as some other Irish saints. Brendan’s tale is based on a pre-Christian legend called Immram Brain (the full text of which can be read here). Here’s a good summary, courtesy of (unlikely as it seems) the University of Texas in Austin.

The text relates how a mysterious woman appearing in the fort of the protagonist, Bran son of Febal, tells him about a magic apple-tree on the island of Emain Ablach, a terrestrial paradise far away to the west of Ireland and abode of the sea-god Manannán mac Lir, which she describes as a place Without sorrow, without grief, without death, without any sickness, without debility from wounds.

Subsequently, Bran sets out to find this island with three times nine companions: on their way they encounter the sea-god, who directs them to an island inhabited by laughing people, after which they reach a different island inhabited exclusively by women. There, Bran and his retinue spend many blissful years, not noticing the passing of time. When finally Nechtan, one of Bran’s companions, is overcome by homesickness, they decide to return to Ireland but are warned by the queen of the island not to set foot on Irish soil. Upon their arrival, Nechtan disregards the warning and immediately crumbles to dust, as they had spent so many years on the magic island that they were well past their dying age; Bran on the contrary remains on the boat and, after telling their adventures to some onlookers on the shore, sets out again for new adventures.

Readers who are familiar with Irish mythology will immediately recognise the similarity of Nechtan’s story to that of the famed warrior Oisín, who goes to live with the beautiful Niamh of the Golden Hair in TIr na nÓg (the Land of Youth), and to whom the same fate befalls when he returns to Ireland.

The muscular statue of a mature Brendan in Fenit, Co Kerry, which is the work of Tadgh O’Donoghue. Below is another image of this wonderful work

But to get back to Brendan – the story of his voyage became the principle Immram of the Middle Ages. Originally written in Latin as early as the 9th century, by the 12th century, it was one of the most popular medieval legends, with versions in many languages: French, Italian, English, Dutch, German, Irish, Welsh, and more. In fact, more than a hundred manuscript versions survive. That does not include the Life of Brendan from the Book of Lismore, compiled in the 1480s, and wonderfully translated by Whitley Stokes, even though that Life contains the voyage within it.

Just to give you a flavour of Stokes’ language, here a little extract from the Life:

So Brenainn, son of Finnlug, sailed then over the wave-voice of the strong-maned sea, and over the storm of the green-sided waves, and over the mouths of the marvellous, awful, bitter ocean, where they saw the multitude of the furious red-mouthed monsters, with abundance of the great sea-whales. And they found beautiful marvellous islands, and yet they tarried not therein.

Brendan and his foster-mother, St Ita. In Killorglin, by George Stephen Walsh

The thing about all these manuscript versions of Brendan’s Navigatio is that none except a couple is illustrated. My recent acquisition (thank you, Innana Rare Books!) is a book about one of only two fully illustrated versions, although isolated illustrations crop up here and there. The book was published in 1980 and is a work of scholarship by Hans Biedermann. Biedermann was a highly respected Austrian academic and an expert on symbolism and mythology. A professor at the University of Graz, he died in 1990, aged only 60. This is the only photograph of him I have been able to find.

This means, of course, that the book is in German, and no English translation exists. I turned to my favourite AI tool, Perplexity, to help me with the translations and it provided me with a page-by-page summary.

This window is in KIllorglin and is by James Cox. It emphasises the scholarly monk in the main panel, leaving the seafarer to the predella

A digression – I am as concerned as you all are about the use and mis-use of AI. For the purpose of this project I used Perplexity as an AI-powered search engine, translator and research assistant, asking it to fact-check items for me, and to dig deeper into sources and references. Because the book is in German, and some of the sources I consulted are in European libraries, I couldn’t have done it without this kind of help. Perplexity also ‘fixed up’ the photograph of Hans Biedermann above, from the tiny fuzzy image which was all I could find online. The writing, however, is all my own – don’t worry, none of this was written by a chatbot.

A detail from a George Walsh window

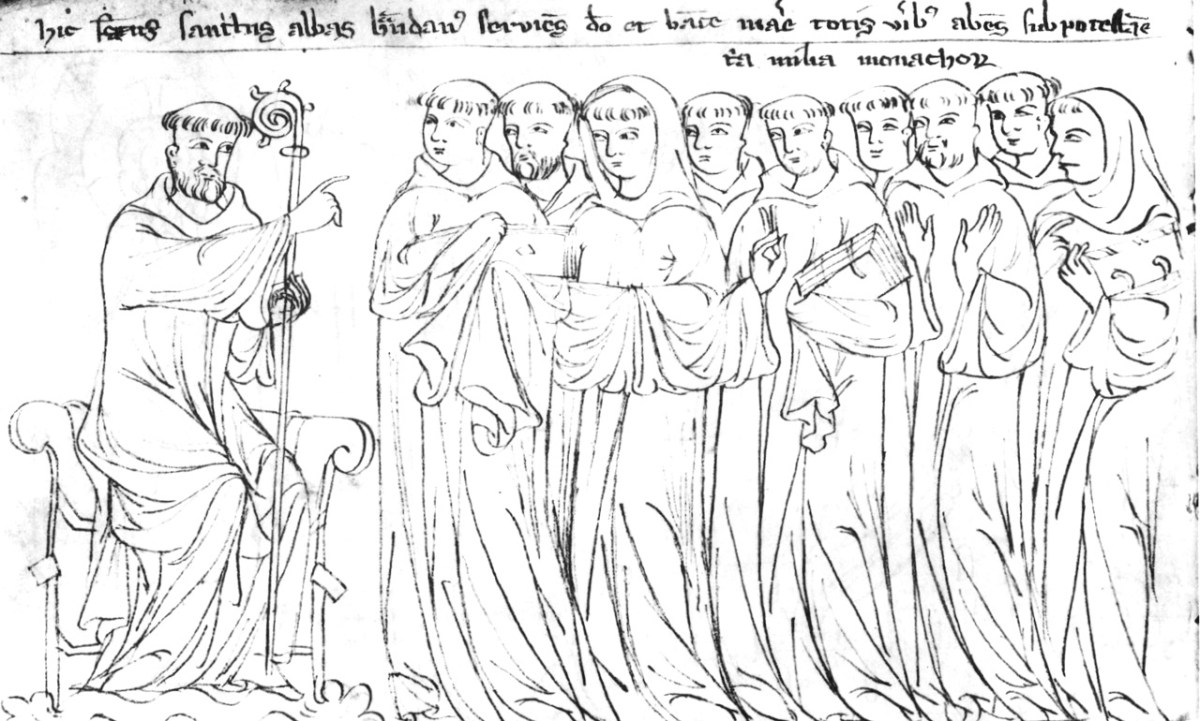

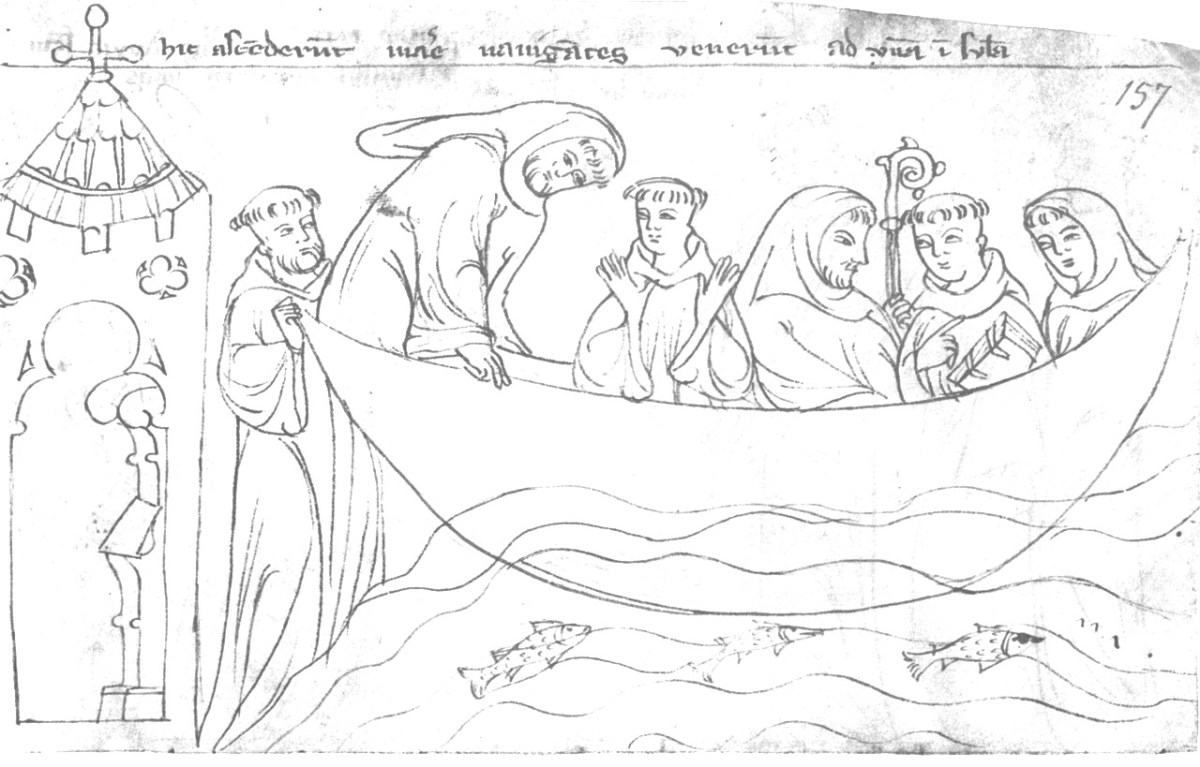

I am also painfully aware that I am many words in and I haven’t actually shown you what the book is all about. It contains facsimile reproductions of 62 plates from the Krumauer Bildercodex, Codex 370, which is a manuscript kept at the Austrian National Library. The plates illustrate the voyage of St Brendan. There is a minimum of text, in the form of captions in Latin in Gothic script. It is, in essence a graphic novel – and it dates to 1360!

Caption reads: Here the holy abbot Brendan, serving God and the blessed Mary with all his strength, had under him nearly three thousand monks

Next week we will get into the illustrations and look at what may have been the origins and the purpose of the manuscript. They are all pen and ink line drawings – above and below is a foretaste.

Caption reads: Here they set out upon the sea, sailing, and came to an island.

Discover more from Roaringwater Journal

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

He must have had an equally epic journey home again, for the story to be told, but I haven’t seen any mention of that! Have you?

LikeLike

Stay tuned!

LikeLike

Fascinated by this! I lived near Ardfert as a kid and we used to play in St. Brendan’s cathedral there. Nearly everything in Kerry is some kind of “St. Brendan’s” including the credit union. When my wife and I were planning to migrate to Canada, we named our eldest Brendan based on the myth and the Tim Severin book. North America was “discovered” by a Kerryman!

LikeLike

Tim Severin will feature – and that glorious music written to celebrate his voyage.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s right! The Brendan Voyage. Must listen to that again

LikeLike

What a find! I’m a big fan of St Brendan and look forward to part 2. Interesting comments above too.

LikeLike

His deeds on land were mighty too.

LikeLike

José Antonio Lopez, MDBeg

LikeLike

I once attempted to analyse the Brendon story as a ring-structured text. I was not really up to the task – as you say, there are so many tellings.

I did come to the conclusion that there is a definite beginning, middle and end, and that all relate. The middle being the moment on the island of birds where they tell Brendon God’s plan for him and his ship.

The journey itself depends upon returns to the same three islands for Good Friday, Eater Momday, and Christmas, so like concentric circlings around these three islands? Nothing in the text I had reproduced a set pattern other than this.

LikeLike

So interesting – I hadn’t thought about it in this way.

LikeLike

The Bran story fits the pattern perfectly, each part repeated in reverse to and from the island, and that the women from the island ‘summoned’ Bran, and then left them with a curse when they left, in each case their intervention was crucial to the tale.

It seems the only voyage story that does fit the pattern, however.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for a great bit of history which must have involved a lot of research.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not over yet!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always enjoy reading your Journal.One small correcti

LikeLike

Your comment got cut off, Jose. The correction?

LikeLike

Aha. A cliffhanger. Well done! JKSent from my iPhone

LikeLike