Last week I introduced you to the modernist stained glass practice known as dalle de verre, and its beautiful realisation in St Augustine’s in Cork. It was the work of the world famous Gabriel Loire. To see what made him so renowned, just take a look at this project, or google the Symphonic Sculpture installation in Japan.

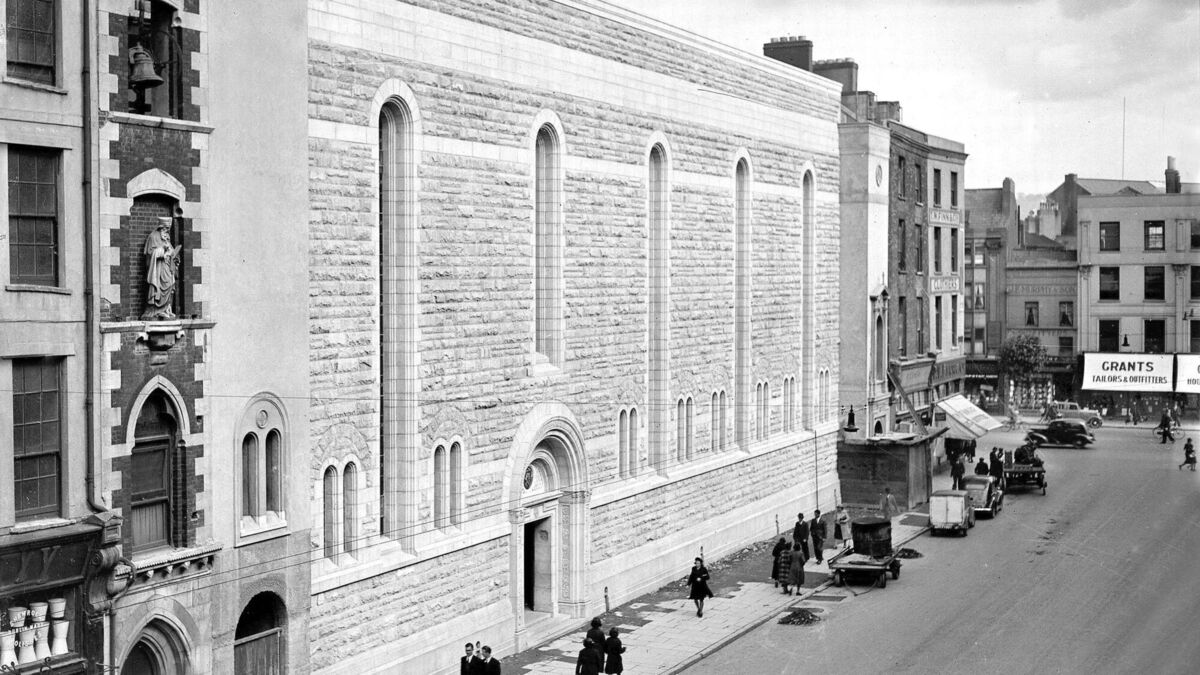

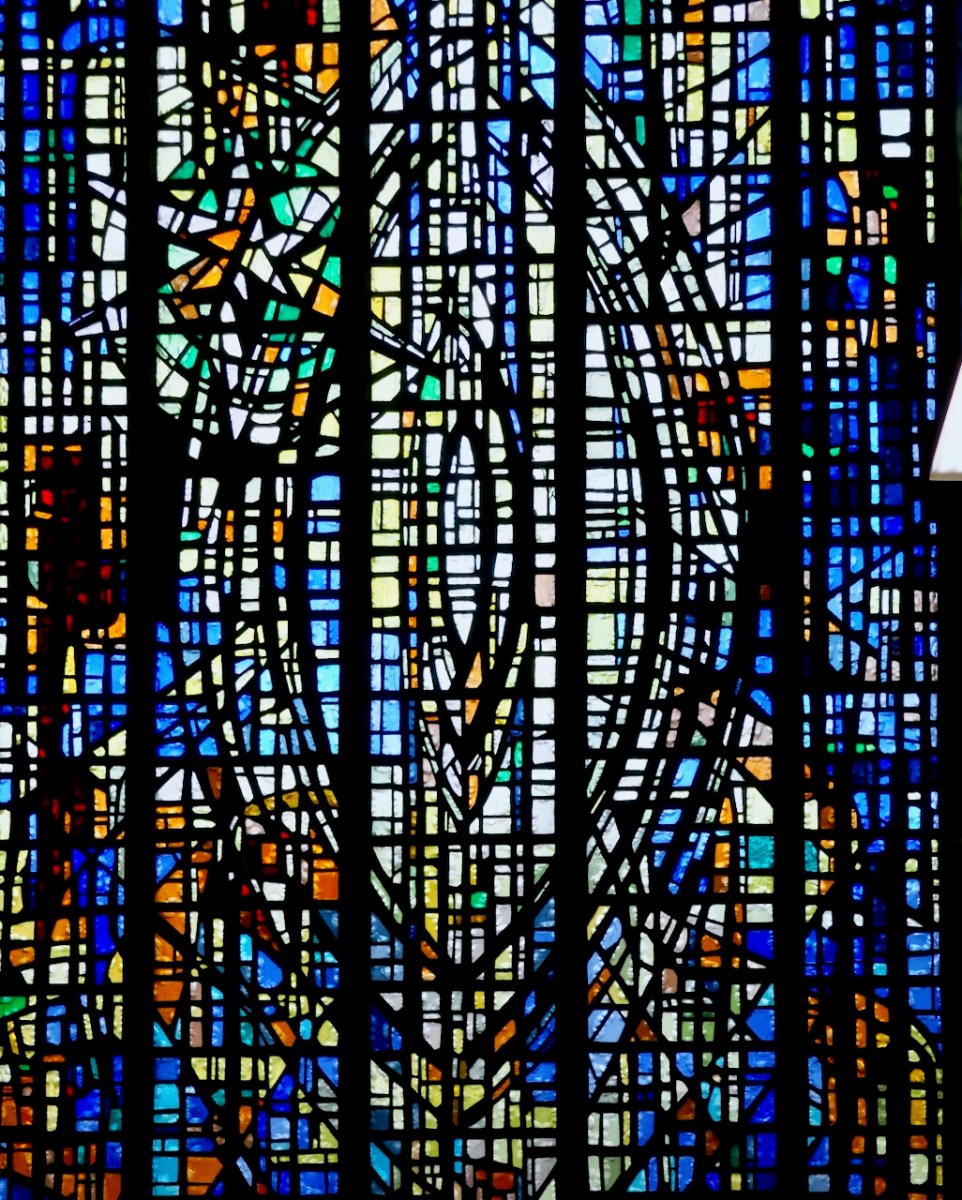

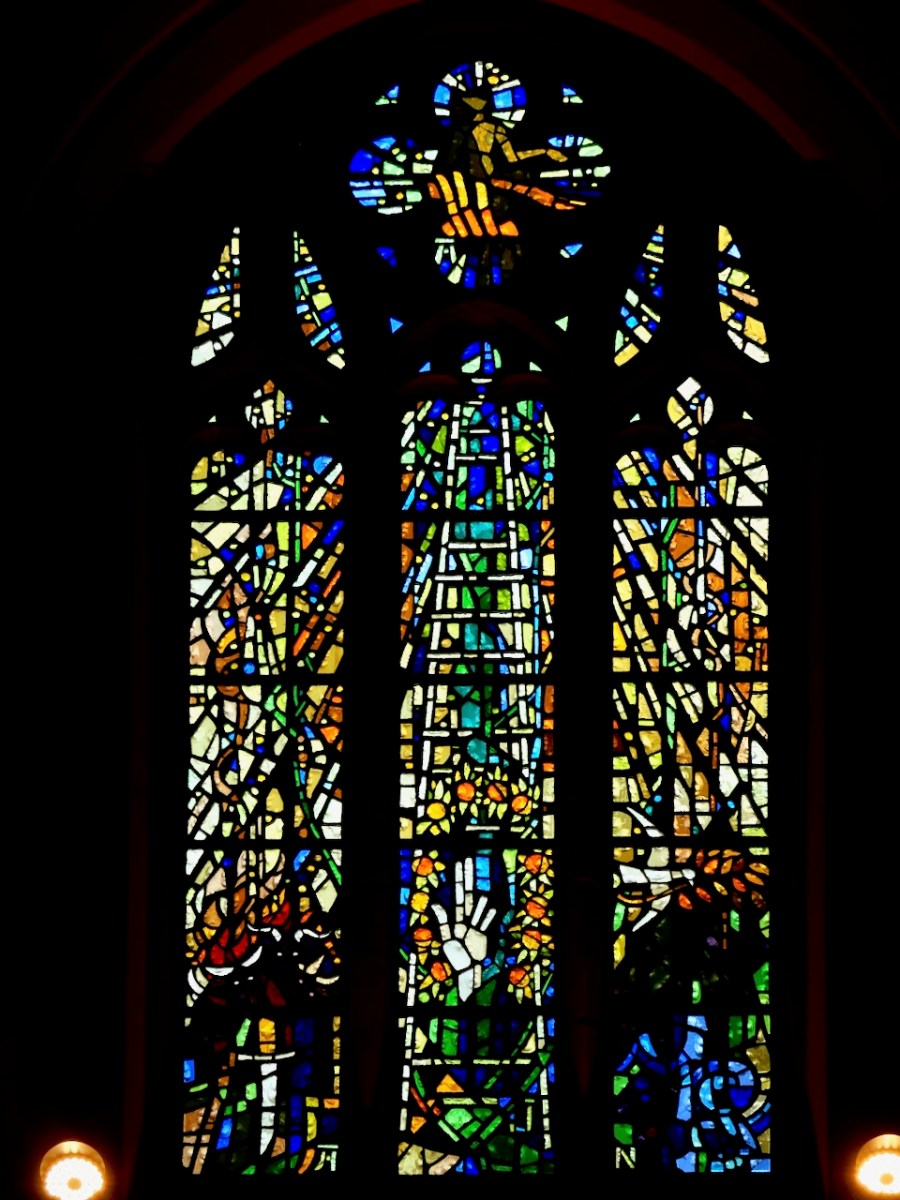

We have three more examples of Loire’s dalle de verre work in Ireland. In a now largely-unused church attached to the Dominican Convent in Belfast (above), we have his earliest Irish windows (1962) – 5 lights titled Resurrection, Redemption, Prediction, Nativity and Annunciation. They are hard to photograph and even harder to interpret – the titles were supplied to me by the Ateliers Loire.

For those used to traditional stained glass, dalle de verre represented a radical departure from their expectations and we must not underestimate the courage and vision of architects and congregations in embracing this avant-garde medium. Rather than a familiar depiction of a Resurrection, Annunciation, or St Patrick, what faced parishioners were swathes of deeply coloured glass sometimes with recognisable iconography, but often with difficult-to-interpret motifs, as in the Belfast windows.

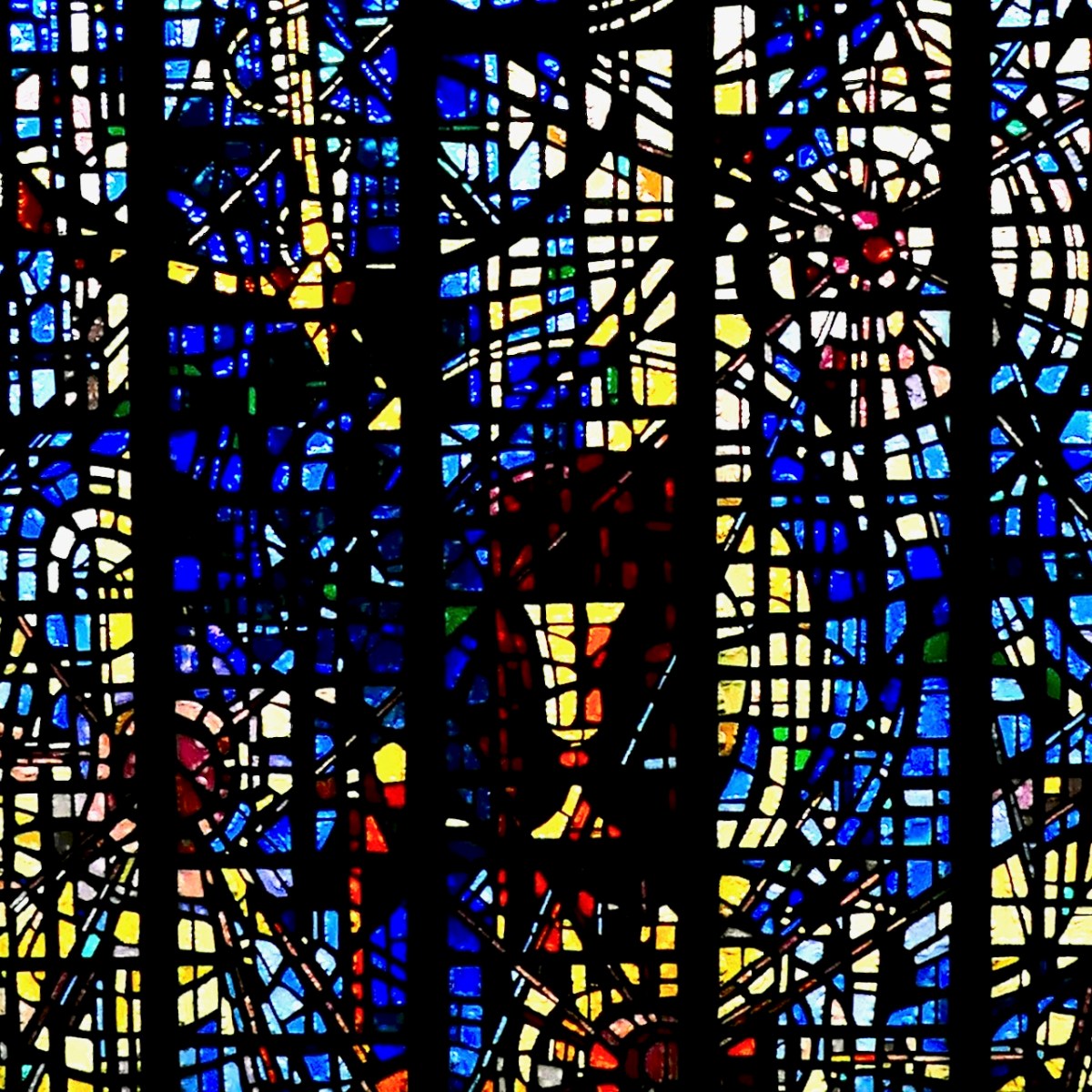

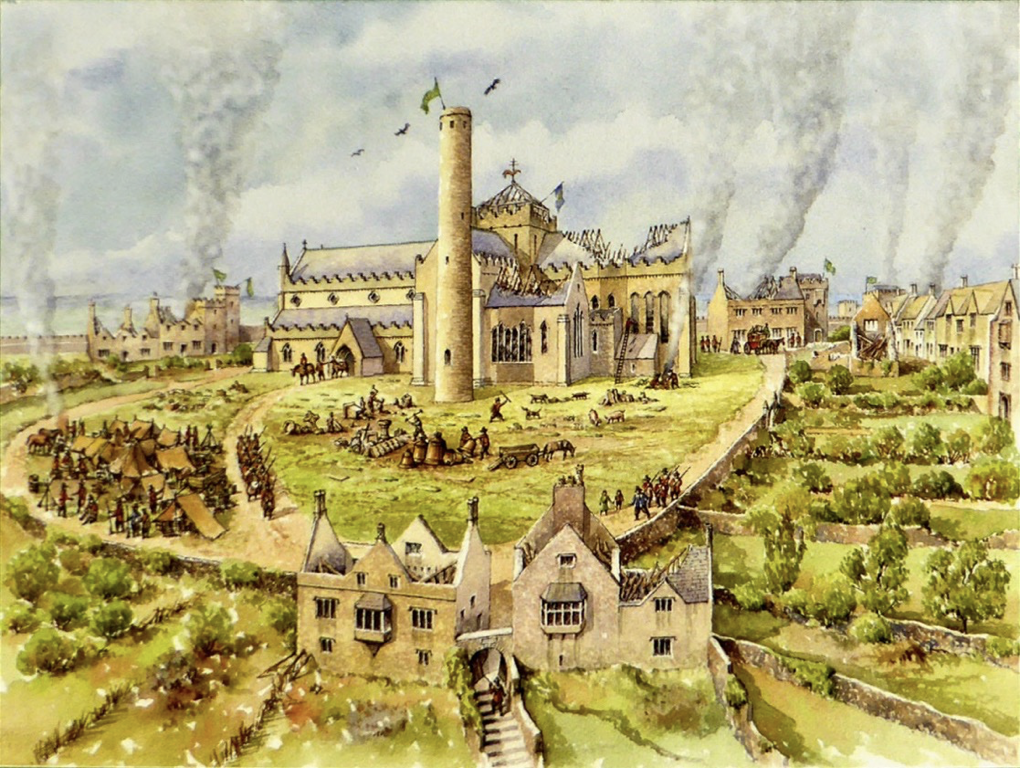

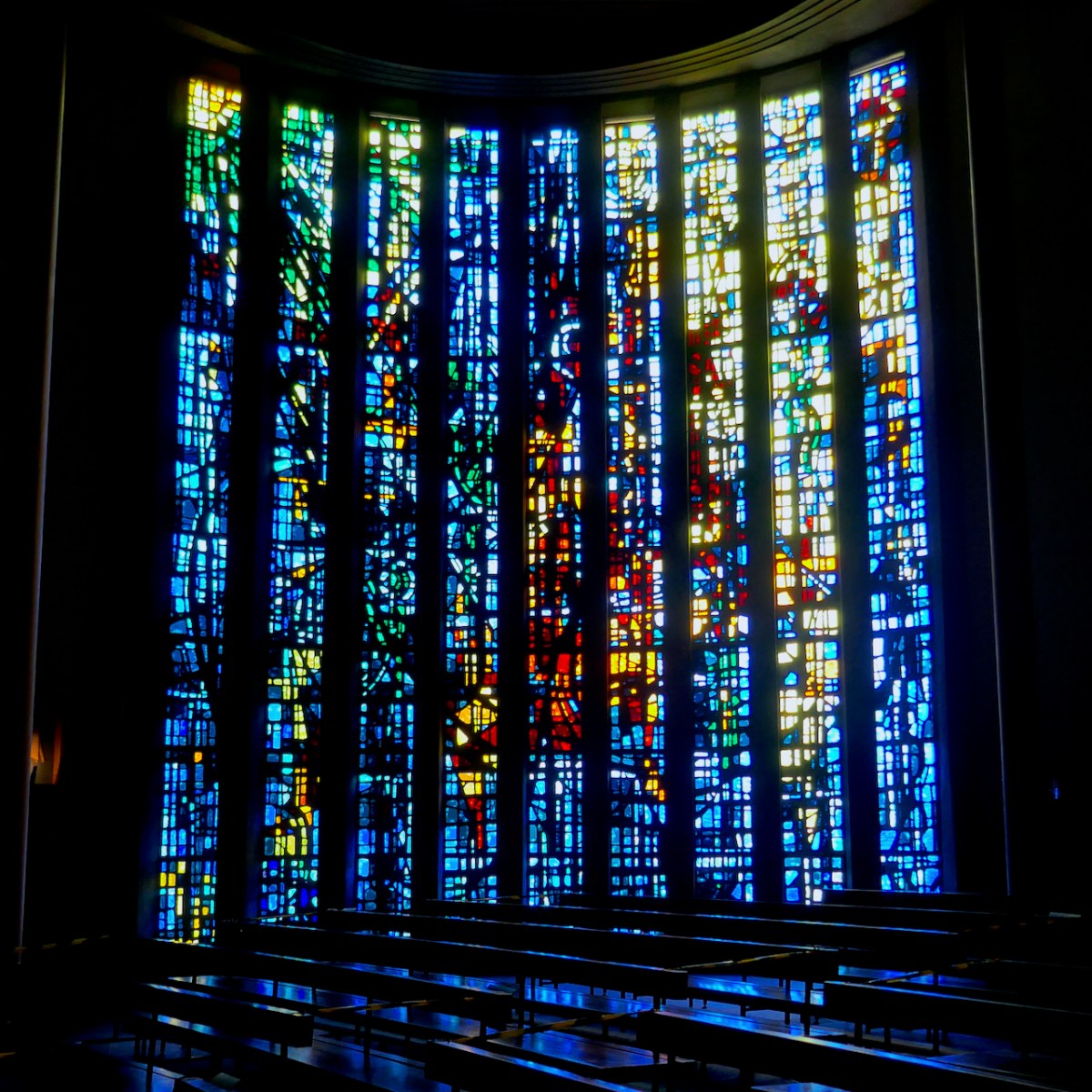

And sometimes with nothing but colour variation to encourage a prayerful or contemplative mood. Gabriel Loire adopted the maxim, Arrange it so that in what you do, there is nothing, but in that nothing, there is everything each person seeks. His philosophy can be seen in action in the Holy Redeemer Church in Dundalk (above) (1965-68), an extraordinary modernist building with work by the best artists of the day. The success of the design can be credited to the architects, Frank Corr and Oonagh Madden, and the breadth of the art to Michael Wynne, who acted as advisor on the project. Works by Oisin Kelly (rooftop crucifixion), Imogen Stuart (exterior stations), Ray Carroll, and Michael Biggs adorn the exterior and interior, while floor to ceiling expanses of dalle de verre by Gabriel Loire provide, in Michael Wynne’s words, one great abstract symphony of colour.

Wynne goes on to say that the windows lend a rich mystical light to the whole interior and to comment on the splendid harmony that exists between the building and all the necessary adornments. Such a unity lends a dignity, a calm and prayerful mood to the building. *

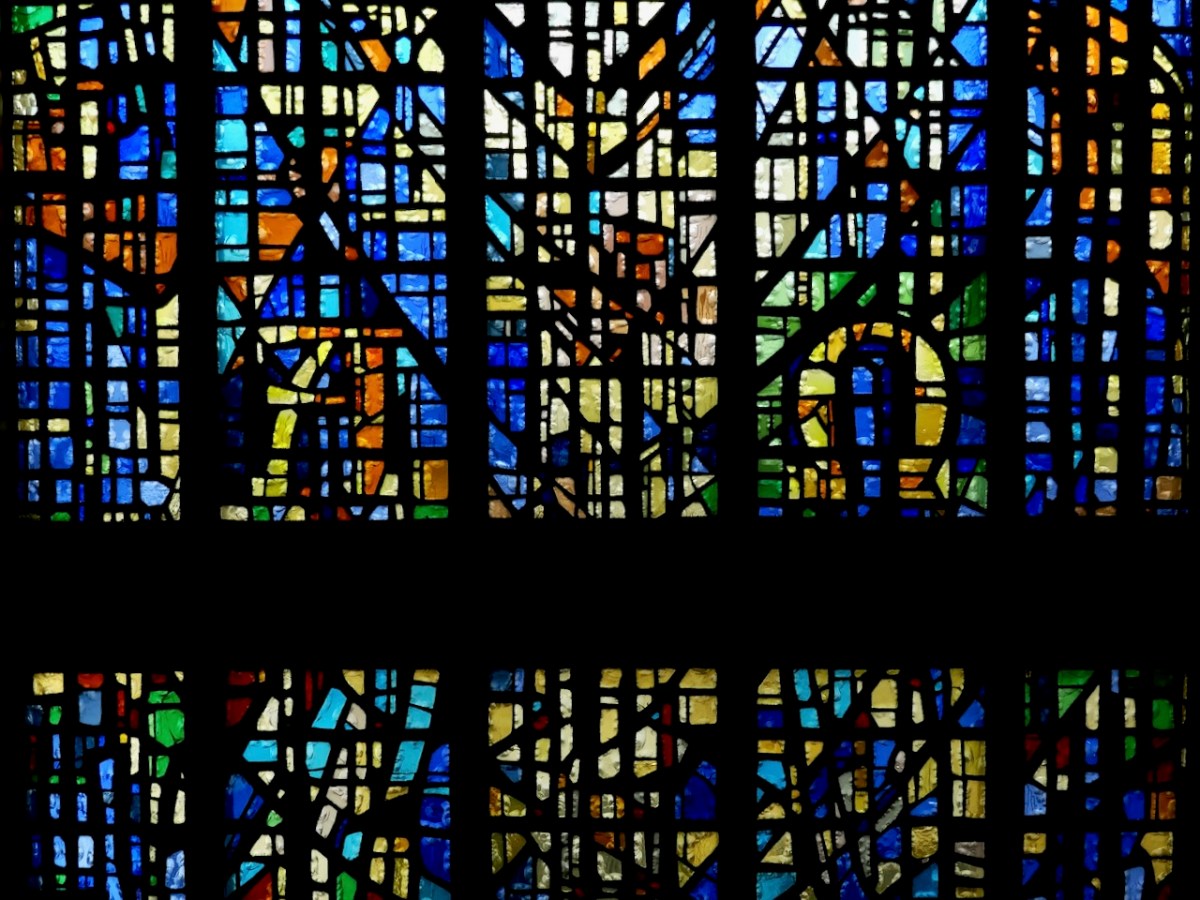

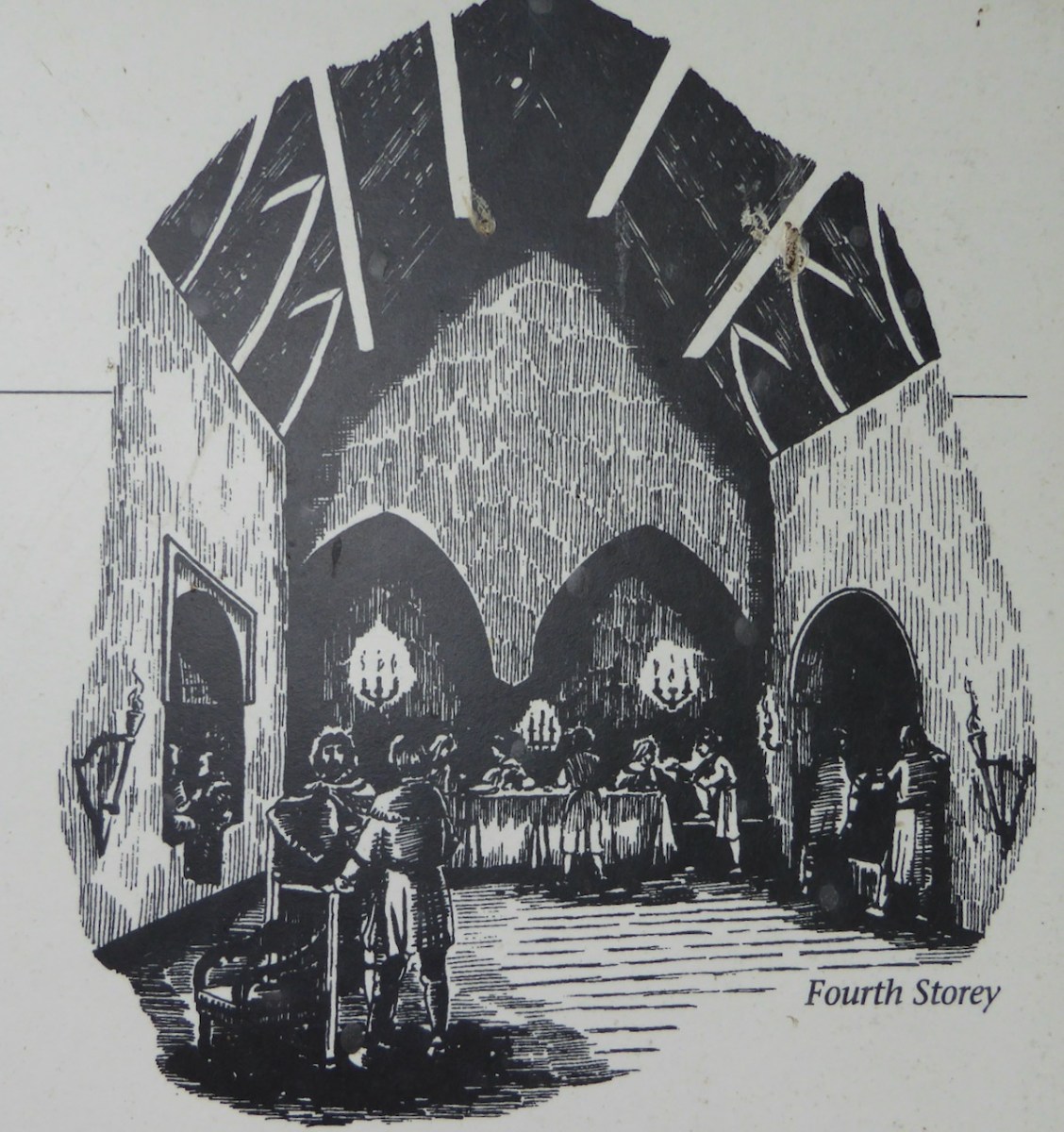

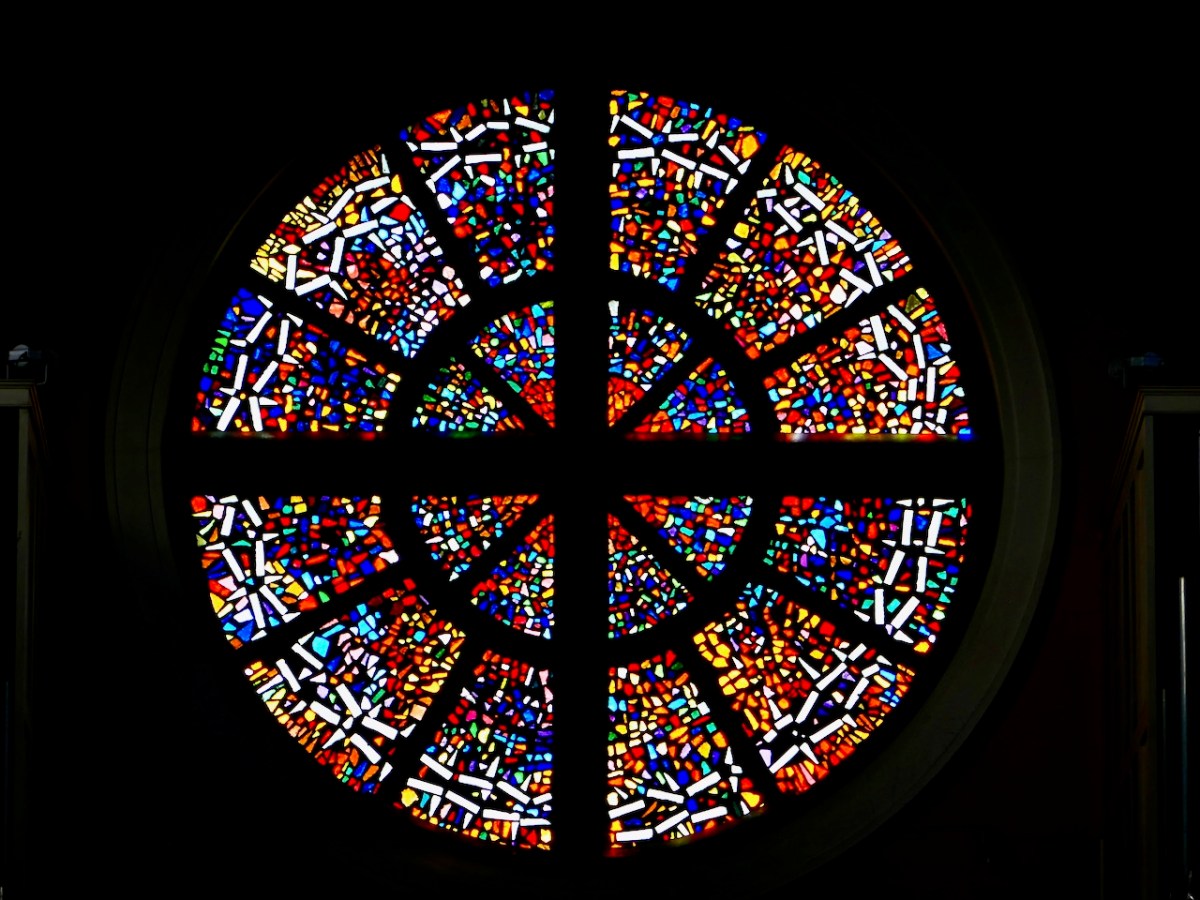

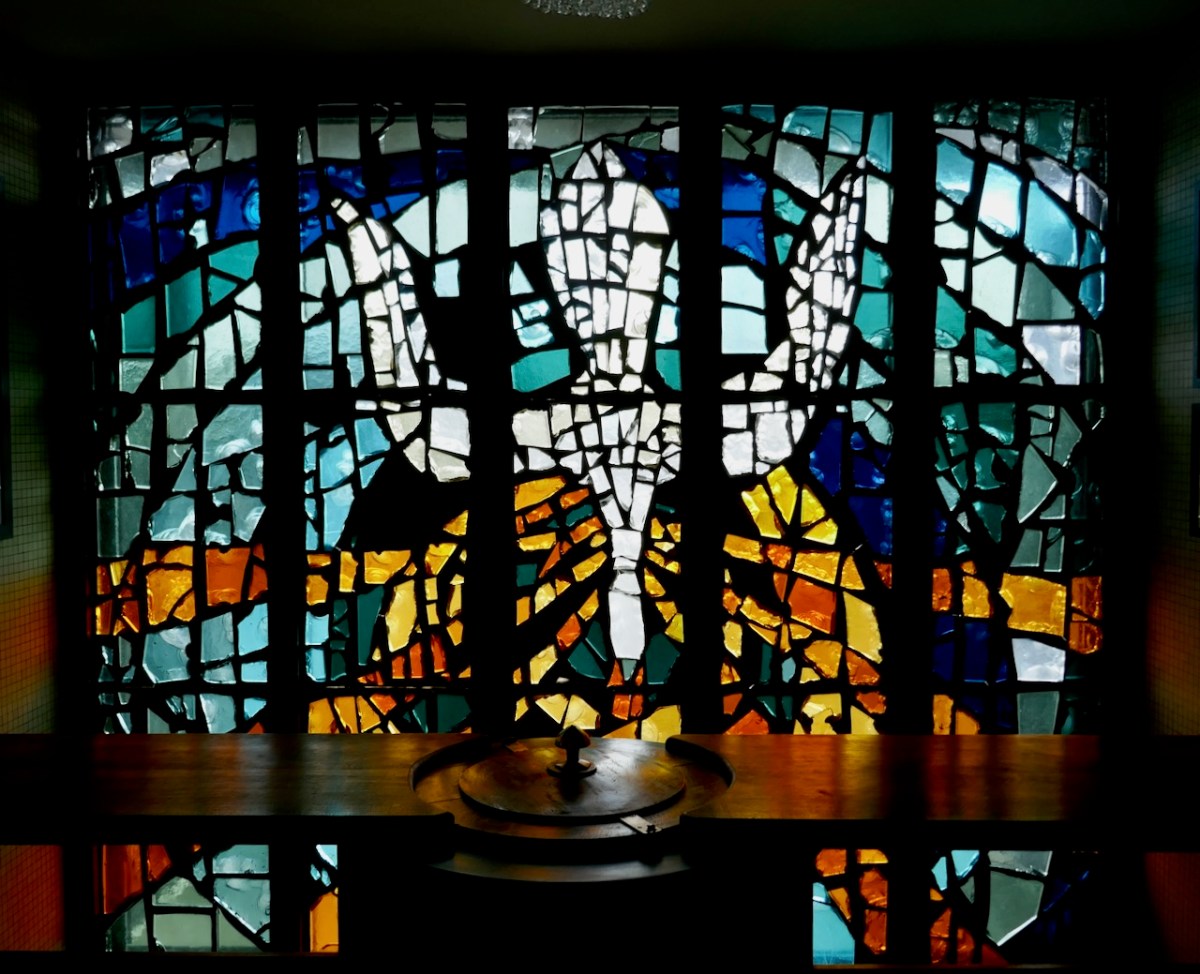

In the Andrew Devane-designed church in St Patrick’s Campus of DCU in Drumcondra, also built in the mid 60s, the curved walls are punctuated by tall panels and a clerestory of dalle de verre. See the lead photo on this post (the one under the title) and the one below. While mostly abstract, some iconography has been incorporated by Loire into the windows.

Because thick lines of concrete are used to outline the images, they are semi-abstract rather than refined. The hand and the dove are clearly discernible in the tall central window, but it cannot be said that the dove is entirely successful – it looks to my eyes like a cartoonish dicky-bird – showing the difficulties of smaller-scale iconography with this medium.

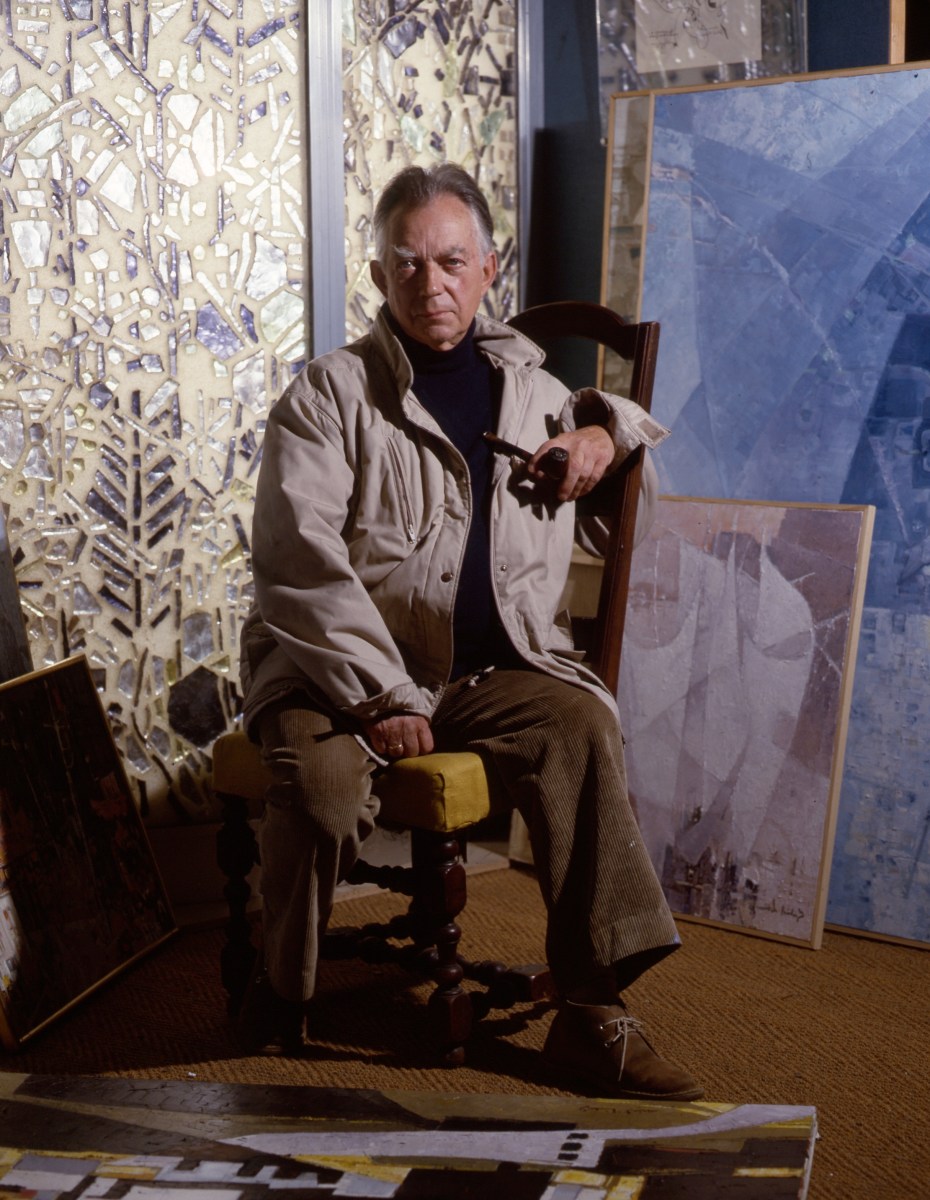

But the Irish dalle de verre story goes beyond Gabriel Loire: other mid-century artists mastered it and were employed by Irish architects. I will show you two examples first by non-Irish artists. The Church of the Sacred Heart in Waterford – it also is my featured image (above the title) for this post – contains glass by the distinguished British artist Patrick Reyntiens. Here’s a detail, below of that window.

The second church is St Bernadette’s in Belfast, with glass by Dom Norris of Buckfast Abbey. This church is well worth a visit for its many artistic treasures.

Irish artists got in on the act too – George Walsh brought the techniques of dalle de verre back with him from America in the 60s and, working with Abbey studios, introduced it as an ecclesiastical art form into Irish architecture. Here is his Crown of Thorns for St Mary’s Westport, designed by George Campbell and executed by George.

Other studios, such as Murphy Devitt, also used it, and quite close to me I have this charming example in Lowertown church. It’s the Dove of Peace/Holy Spirit, of course, but it became known in the studio as the Holy Gannet.

Although for the most part the churches I have shown you have retained their dalle de verre windows, in at least two cases (the Sacred Heart in Waterford and St Bernadette’s in Belfast) this has come at the cost of enormously expensive conservation projects. In other cases, dalle de verre windows have failed and churches have even had to be demolished.

For example, the original Edmund Rice chapel in Waterford (above) had to be replaced but George Walsh’s dalle de verre windows were partially saved and displayed in the new church (below). George had combined dalle de verre in these windows with the innovative use of painted glass panels, and even some painting on the dalles.

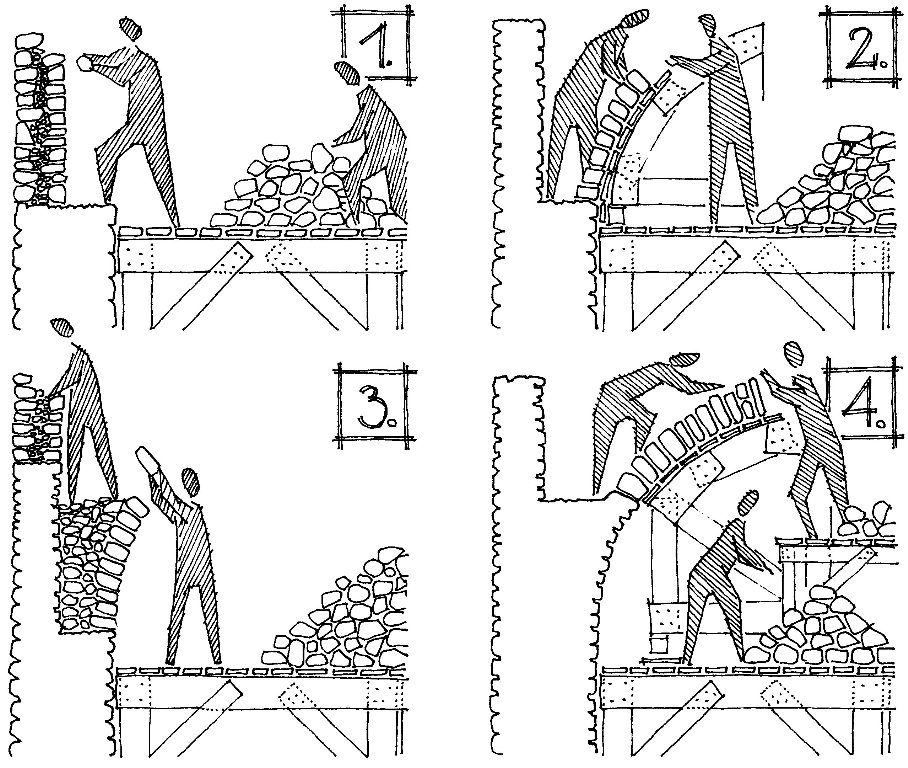

Dalle de verre windows failed because glass, concrete and steel (used to reinforce the concrete frames of the panels) expand at different rates, and external glazed walls are subject to all the effects of weather. Over time resin was substituted for concrete but this brought its own problems – the epoxy mix had to be just right (and this was all still experimental) or it could, and did, twist and crack as the building settled. The Irish climate – high humidity, temperature fluctuation, driving rain – exacerbated all of these mechanisms, both for cement and resin mixes.

I recently visited a church in Keenaught Co Derry (or Londonderry for my NI readers). It has a soaring wall of dalle de verre windows designed by George Walsh and executed in the Abbey Studios in 1973. The likeness to the work of Gabriel Loire is obvious and indeed George credits Loire as a significant influence on him. The church is enormous and the tall narrow windows lend a beautiful ambience to the interior. However, the windows are buckling at the top and will need conservation work at some point.

On the same trip I visited a much smaller dalle de verre installation in Swanlinbar, also by George, still looking colourful and rock steady in a side chapel.

I’d love to hear from readers who have come across other examples of dalle de verre work. As an architectural material it held such promise and it is a tragedy that much of it is no longer standing. The Gabriel Loire window below is from Vancouver, part of a series in St Andrew’s Wesley on Burrard St, viewed on a visit there. I had been in that church for events on numerous occasions when I lived in Vancouver, but knew nothing about these fabulous windows at that point.

By the way, Ateliers Loire is still going strong in Chartres, now run by Gabriel’s grandsons, Bruno and Hervé. Take a look at their recent work. And for anyone looking to learn more about Gabriel Loire I recommend this book which is in French and English. [Update – see comment below re the cost of this book!]

Finally, some of the text (now lightly edited) in this and the previous post on dalle de verre was originally written for a 2021 article on Dalle de Verre in Ireland in Glass Ireland, a publication of the Glass Society of Ireland. The full article is available here.