We’ve established a little tradition for Christmas: we include a story, ideally to be read by candlelight huddled beside the stove just at the turning of the shortest days. Last year Finola wrote of childhood memories – Christmas in Dublin; the year before that I penned a version of a haunting Irish folk-tale. This year it’s my turn again, and I’m including a story which is based largely on events which really happened many years ago in the small Devon village where I lived. They bring to mind our own stormy winter which we survived earlier this year here in Nead an Iolair…

Kathleen by Robert

Kathleen was a large woman alright. If you saw her in the field, there was no mistaking her profile: she always wore two coats, one on top of the other, and at the bottom they flared out like a church bell. I never saw her without her great legs jammed into a pair of old wellington boots – except in chapel of a Sunday – and on her head was the same shapeless piece of faded red knitting, year after year after year.

Kathleen became a neighbour of ours soon after Mr Monihan’s passing. – And there was a strange thing, too. I never heard it from Kathleen’s mouth direct – but then I never heard her deny it either – but everyone in the village was sure enough of the story. He had been a smallish man, I suppose; certainly, he was small by comparison with Kathleen. They shared the marriage bed late in life, for he’d taken herself – a confirmed spinster – as his second wife long after his own children were out in the world.

Well, it was about two years into the union that Kathleen first noticed her husband’s night wanderings. She would wake in the morning – so the story goes – and find him cold and shivering beside her, with the smell of the sea all around. Time and again this happened, and because he would say nothing about it, she determined to find out what was going on. A certain night they went to bed as usual; she lay quiet but kept herself awake by repeating the Our Father over and over into the bolster. It came to the deepest part of the night, and Mr Monihan seemed to be peacefully asleep, while Kathleen was feeling very tired and wondering what she was about. Suddenly, he started up, crept across the room to the door, and in a minute was out of the cottage. He had paused only to put on his old black cape that always hung on the peg. Just as quickly, Kathleen was out too, but she was careful to keep hidden away behind him. Down the hill they went, through the sleeping village and out on to the beach, he walking so fast that she had some difficulty in keeping him in her sights. Eventually, she lost him altogether in the rocks over by where the cliffs start. She searched for an hour and then gave up, returning crossly to her bed.

In the morning he was back again, but cold and shivering as usual. Kathleen went over to the peg by the door and felt his cape: it was streaming wet, and flecks of sea-foam still clung to it.

Of course, Kathleen confronted him with the story and wanted to know what it all meant. He just shrugged and claimed to know nothing of it; as far as he was concerned, he had slept all night in his bed and woke up in the morning as cold as any old man would be. So there was a pretty poor state of affairs for Kathleen. But she accepted it in the end, as we all accept the mysteries in our lives. She did try to follow him again, but had no more success than before. She closed her mind to it and denied its happening, even to herself.

A while after, he was gone altogether, and his black cape with him. She waited a day and a night, then went down to the rocks to search for him. He was never found, and everyone accepted that he was drowned while in pursuit of his trade, which was kelping.

After that Kathleen moved up the hill into the little thatched cottage across the lane from us, and took up the kelping herself. I would often meet her coming across the sand of an evening, the great dripping net slung over her back and she bent with the weight of it. Yet I never heard her complain, and she a widow so soon.

She was not companionless for long. One of her husband’s daughters who lived away in the city with a family of her own fell on difficult times and sent her own son to stay with Kathleen. This was a weak looking boy of about fifteen years old. The arrangement was meant to help Kathleen as well as the mother, but I never once saw him lift a kelp net, and doubted if he was even able. Instead, he followed her around like a dog, and seemed more of a worry to her than ever her widowhood had been.

What happened after was only learnt by the villagers in the course of time, and much of it hearsay in any case, as Kathleen always kept herself to herself. She must have been aware of the stories that went about but was never known to confirm any aspect of them. On the other hand, she never uttered against them, so they are probably worth the telling. I saw little enough of the events myself, although I was aware at the time that Kathleen was in some way troubled.

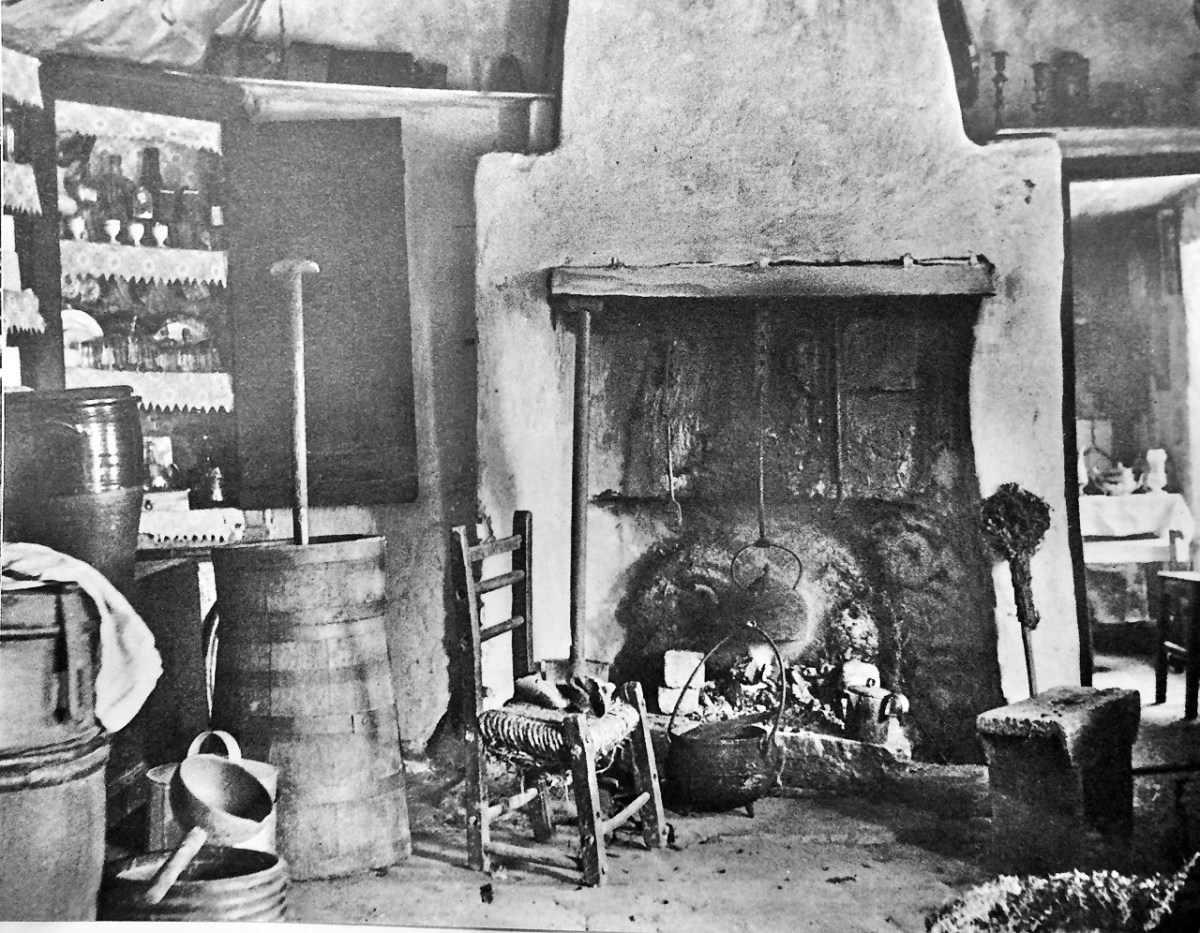

It was late in the year; nights were long. The cottage had only one bedroom – Kathleen’s – and the boy slept on a settle in the kitchen. On our wild coastline, dawn is hailed not by a cock’s crow, but by the first wailing of sea birds that collect in huddled crowds over the off-shore rocks. One of these winter mornings Kathleen was just stirring herself when she was startled to find the boy standing by her bed. He had thought that she called him – somebody or something had called him – so he came from his place on the settle to see what was wanted. She paid little enough heed of it the once, but when it happened again a second and a third night, well – then she started to worry. On the fourth she stayed up, sitting herself in a hard chair by the embers of the hearth so that the discomfort of it would keep her awake. She kept the Good Book beside her. She was determined to wait the night out, but drowsiness overtook her and she suddenly awoke in the early hours to find the boy had sat bolt upright and was staring sharp at the cottage door. He seemed not to hear her when she spoke but eventually came to, like one shaken out of a dream, and told her that – again – there had been the voice crying to him in the night. She made light of it, and convinced him it was no more than the wind and the sea, but inside herself she knew there was something else.

After that, Kathleen could not rest easy without taking the precaution of fitting a large lock to the door which faced down the shore road – something she had never lived with all her life before – and when she went to her bed at night, the key was firmly under her pillow!

The solstice passed, and days grew longer. Gales came, as they always do in January on our coast. But in that year these were savage gales, far wilder than anything I had experienced in my lifetime. The glass in the hall fell and fell again, until the little brass pointer was hard against its bottom stop. We kept around our firesides, then, and listened to the storms hurling themselves against us, our windows and doors rattling and moaning from the wind wanting to tear us from our refuge. Some days there would be a little respite, and we would venture outside to pick up the broken slates and chimney caps that littered the lanes and gardens. At these times, we saw how the sea had thrown itself halfway up the village street as though angrily trying to reach out for our hillside homes, having already washed over those against the harbour. There was no kelping could be done – the huts on the shoreline were in any case smashed and the nets all gone – but Kathleen could never be idle: she feared for her roof and I watched her throw thick cords across the ridge of it, and lash them to great boulders at the eaves to weigh it down. All this she did from ladders with the wind still high, she heaving the heavy rocks on her own while the boy stood under her, useless as a lame sparrow.

These lulls were short, and were each time followed by yet worse weather. The peak of it came towards the end of the month, with a roaring wind that you could not stand up against. It brought our chimney down, and the church steeple too, which went through the nave and ruined it. A day and a night it lasted with us all crouching indoors, wondering what havoc we would find around us if ever we survived.

The morning that followed after was, unbelievably, as quiet and as calm as spring. There was not a breath of air moving; the wind seemed to have blown itself right away. We crept out and viewed the devastation. It was bad, but it could have been worse. There would have to be a lot of roofing done, but generally the old stone walls had taken the battering well. In the course of time we were thankful to discover that no-one in the village had suffered injury to themselves. Like us, they had each one hidden away by the safety of their own hearth. Kathleen was not so relieved however, and I realised her agitation as soon as I crossed the lane to find how she herself had fared. She showed me where her door lay half in and half out of the tiny porch, as though it had been picked up in the night by some gigantic hand. The rest of the cottage was undamaged, the roof intact under its protection. But the boy was vanished.

We got together a search party as soon as it could be managed, and went after Kathleen who had gone straight down to the rocks at the end of the beach, close under the cliff. All that day and all the next we searched, but never a trace we found. I happened on an old black cape lying half in one of the pools but left it for the tide to take back again.

A few years have passed since these things occured. The winds have never been as rough again as on that night when Kathleen’s boy was lost. The village gradually got itself back to normal, and the sea has done its best to wash over the memories. The cottage across the lane is unchanged, except that it has a new entrance door. I often meet Kathleen striding across the beach with her loaded kelping nets: I would like to ask her if she still locks herself in at night.

The gale found us again this last January. I lay in bed unable to sleep for the fury of it beating itself over the sea walls. Or perhaps I did drowse – for I fancied that just before daybreak the storm dropped, and from beyond it there came a faraway sound unfamiliar to me, as of someone calling out of the night. Calling my name. I shook myself properly awake. No, I could not still hear it; it must have been one of the sea birds on the islands shouting in advance of the dawn chorus. In the morning I went down to the beach. There was Kathleen as usual, pulling through the combings of the high tide with her long wooden rake. I passed her by, and walked out to the end of the sands, where the cliffs begin. I had thought that the sounds of the breaking surf would wash the night-cries from my ears or my head. Yet they still rang clear inside me. I started, then, when I suddenly came upon two figures – they were two great black seals who when they saw me threw their heads in the air and cried out, and their cries were carried away by the wind over the village and over the hills. I watched as the creatures slid back clumsily across the sand until the water took them. Still they cried as they swam away, their snouts raised up through the racing froth. At the far end of the beach I saw a small stooped figure – Kathleen it was – raise her hand briefly to her eyes to watch after them.

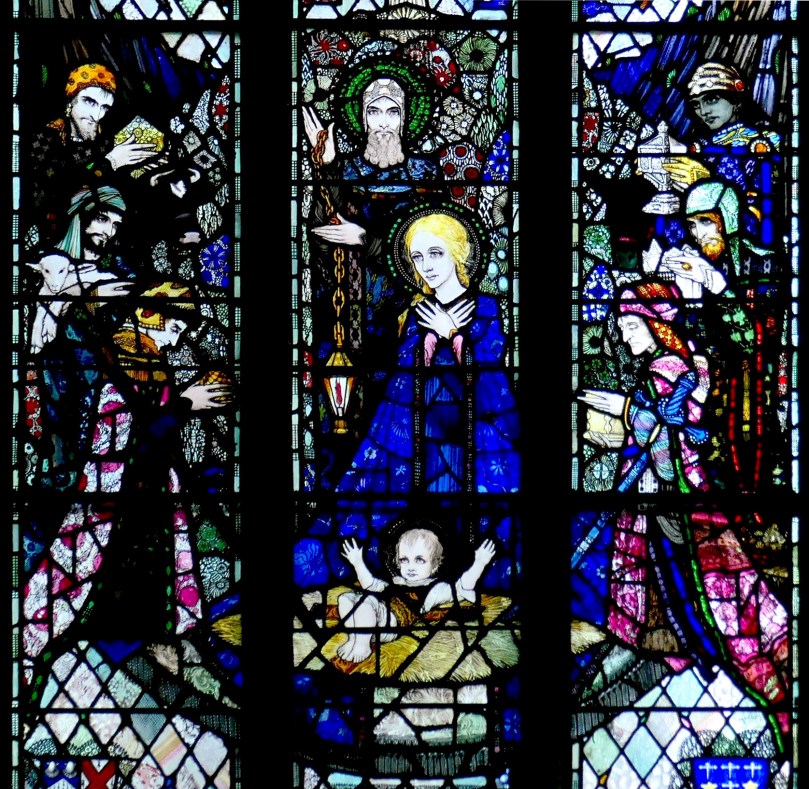

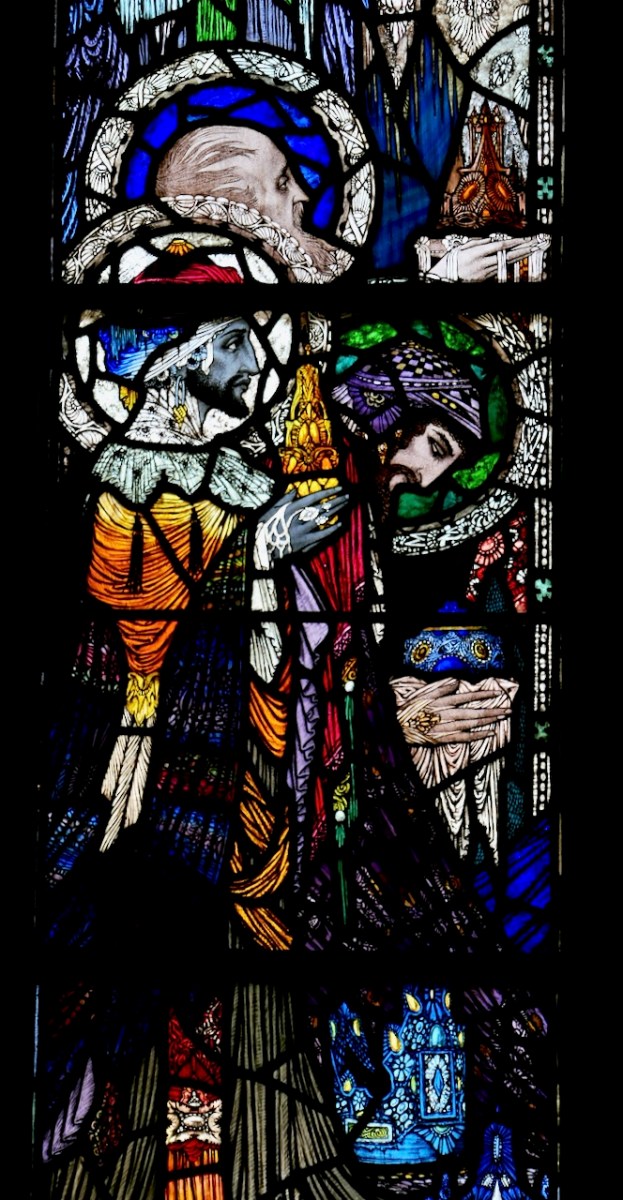

The church in Hatherleigh, Devon, destroyed by the hurricane of January 1990

Email link is under 'more' button.