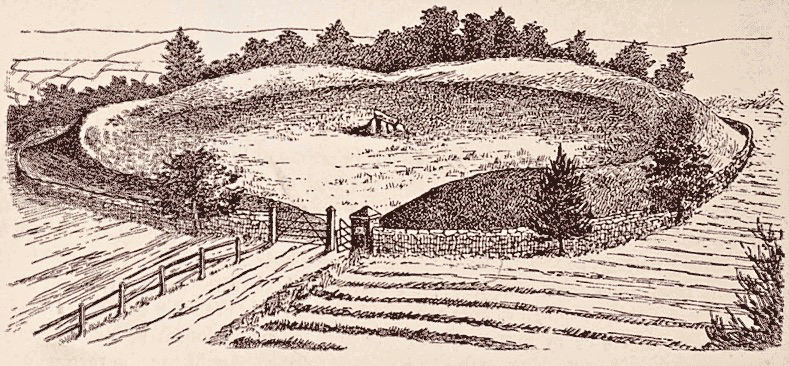

It’s not West Cork, but – if you are looking for an impressive archaeological site – take a little trip over the border into the North, as we did very recently. Just outside Belfast City we found The Giant’s Ring. The size of it is astonishing – 180 metres in internal diameter, and covering an area of 2.8 hectares. And what we see today is only part of a cluster of monuments here.

This marked up location plan, produced by archaeologist Barrie Hartwell in 1998, shows the Giant’s Ring, and other sites nearby which have been discovered by aerial survey and crop marks. We can’t really know what the focus of the whole complex is. Guesses are made as to what its function might have been, based on similarities to other finds, but the size of this ‘Ring’ sets it apart from most other equivalent discoveries. If you want West of Ireland comparisons, then Drombeg Circle has a diameter of 9.3 metres; The Giant’s Ring, at 180m, is twenty times greater! Also, the Grange Stone Circle in Co Limerick – which appears very large to us (it’s the Republic’s largest) – has a diameter of ‘only’ 60 metres.

It’s hard to judge the scale from a photograph, but looking at the figure just visible at the right-hand edge of this view, above, helps to set the scene. The ‘small’ pile of stone that you can also see within the enclosure is, in fact, a monument in its own right, generally thought today to be the remains of a passage grave. Here’s a nearer view, followed by close-ups. The structure – a type which used to be called a ‘dolmen’ (and still is in some of the accounts of The Giant’s Ring) is quite substantial.

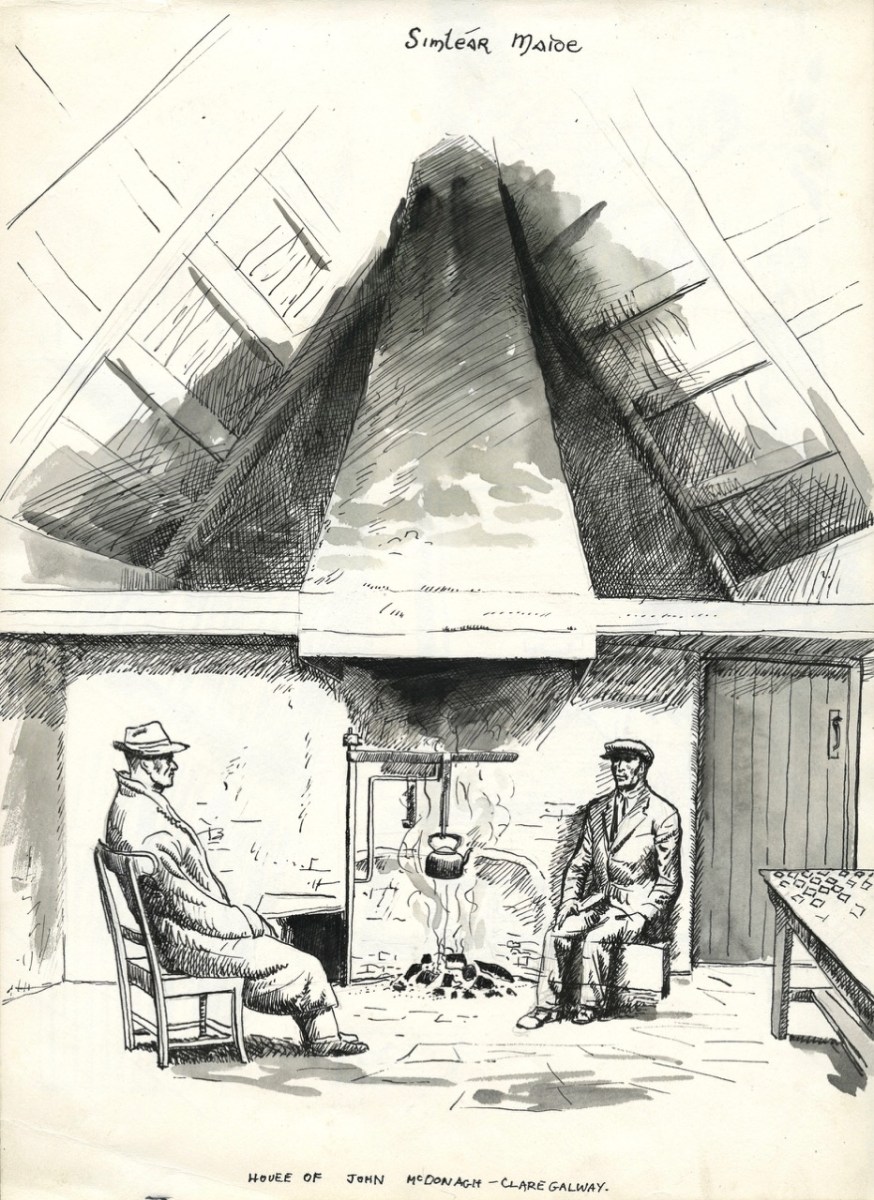

This passage grave is far less impressive than – say – Newgrange, but why would it be sited in this enormous ring – which resembles a ‘henge’? It is dwarfed by the huge circular bank. It is likely that the grave or tomb structure was covered by a mound. Here is an artist’s impression of the enclosure being used for a ritual purpose:

In 1995 archaeologist Barrie Hartwell provided the following commentary to this sketch:

. . . This conjectural reconstruction of the Giant’s Ring brings together a number of ideas. Here the Giant’s Ring stands on the southern edge of a plateau overlooking the fertile land of the Lagan Valley. The internal slope of the bank is lined with stones and the bank has a flat top on which people crowd to view the spectacle unfolding within. The passage grave, embedded in an earthen mound provides the focus of activity. The quarry ditch can be seen between the two. In the right foreground is a circular bank, first seen as a crop mark in an aerial photograph. This was excavated in 1991, when the remains of a stoney bank were found on the eastern side. The central area had been removed by quarrying to a depth of 3m and backfilled within the last two hundred years . . .

Prehistory of The Giant’s Ring & Ballynahatty Townland

Barrie Hartwell LISBURN.COM

Above is an image from Google Earth showing the context of the circular monument in its immediate surroundings. There is no sign in this image of the many nearby sites which have been identified close to the Ring (look again at Barrie Hartwell’s location plan), but archaeologists have been busy at this location in comparatively modern times. Hartwell summarised some of the excavations in an article for Archaeology Ireland Volume 5, No 4, Winter 1991. He reports a description of a ‘chamber’ that was described in 1855 by Robert MacAdam, editor of the Ulster Journal of Archaeology:

. . . On November 21st 1855, Robert MacAdam picked up the Belfast Newsletter in his office in the Soho Foundry in Belfast . . . His attention was caught by a paragraph in the paper announcing the ‘discovery of an ancient tomb on the farm of Mr David Bodel of Ballynehatty’. He immediately visited the spot, just six miles south of Belfast, with his friend Mr Getty, and found that the tomb was still largely intact and that most of the contents had been rescued by the farmer. Equally interesting was its position close to the great enigmatic banked enclosure of the Giant’s Ring on an isolated, undulating, upland block of land overlooking the River Lagan. They were impressed enough to return at the weekend with other members of the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society to record it properly . . .

Archaeology Ireland Volume 5 No 4 – Winter 1991

The above illustration accompanies the article. Note that this find appears to have been sited outside of the Giant’s Ring itself. Hartwell’s account continues:

. . . Their plan and description shows that this curious structure had been built in a paved, 1.5m deep, flat-bottomed pit and with a corbelled roof supported by a stone perimeter wall, five internal stone dividers and a central prop. The top of the roof was 0.5m below the ground surface and may have been covered with small stones to form a cairn. In two of the radial compartments so formed were found the remains of four ‘…urns, about twelve inches high by ten broad…’ each containing burnt bones. One of the urns had disintegrated, and two of them were later described as being large and rudely formed. One of these survives today as a Bronze Age Collared Urn. The fourth was a typical globular-shaped Carrowkeel Ware pot usually found in Neolithic passage tombs . . .

Archaeology Ireland Volume 5 No 4 – Winter 1991

I found a further reference to the discovery of this ‘chamber’ in the archives of the Belfast News, 1855:

Hartwell’s fascinating account describes other finds in the area, and reports how Bodel – the farmer who owned the land – could remember stories of previous finds going back through generations of his family: a number of sites had been destroyed through agricultural clearance or ‘treasure hunting’. According to his memories these included a standing stone, another megalithic tomb, a multiple cist cairn, a number of single cist burials and two ‘cemeteries’ which produced many cart-loads of human bones. He also noted that similar sites had been found in his neighbours’ fields.

We can distil from these various stories that what we see today at this site was central to a very significant cultural hub, much of which is now lost. Hartwell suggests that some of the more recent excavations provide evidence that human activity here dates from 3039 to 2503 BC. His conclusion is significant:

. . . It is placed firmly in the late Neolithic rather than the Bronze Age. The closest parallel in Ireland is surely Newgrange. Indeed, the Bend in the Boyne and the ‘Loop in the Lagan’ invite close comparison. The scale of the monuments may vary but all the elements of a ceremonial landscape are there – passage tombs, henges, pit circles, flat cemeteries, and, of course, the river. Just as the river at its extremities defines a natural region, it mat also have defined a human territory with the ceremonial centre at its hub . . . Ancestral rights to territory were anchored by a thousand years of burial rites and the sanctity of the land shown by the continuum of ritual from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age . . .

Archaeology Ireland Volume 5 No 4 – Winter 1991

Former landowners of the estate on which this monument stands were the Dungannons of Belvoir House. In the mid nineteenth century Lord Dungannon built a protective wall around the Giant’s Ring (shown in the top sketch which reportedly dates from 1897). The plaque on the entrance gate (above) marks a visit to the site by Countess Dungannon, presumably to commemorate the completion of this wall.

The site has understandably attracted artists and photographers. The upper photo by R Welch dates from 1902 and the centre photo by S Kirker dates from 1905. The old postcard, above, is undated, but is remarkably similar in its viewpoint to the 1897 sketch – which one came first?

So there we have it: a very significant ceremonial site which has been compared in importance to Newgrange. What was it for? A burial place imbued with connections to an afterlife? We cannot know. But my own thoughts when looking at this vast circle is that in the present day we would call it an ‘arena’, and we might use it for sports, drama or processions. In fact I noted a report that stated it was used for horse-racing in the eighteenth century. A significant disappointment for me is that I have been unable to find any folklore or ‘stories’ about The Giant’s Ring. Northern Ireland does not share the equivalent of the Dúchas Folklore Collections which we have in Ireland, dating from the 1930s. There must have been tales told about it through the generations: I would be most interested to hear from anyone who can fill in this omission, please.