This week the Augustinians in Ireland announced that they were permanently closing their Cork Church, St Augustine’s at the corner of Grand Parade and Washington Street. The decision, as far as I can see, is based on the inability of the order to attract more vocations – they no longer have the priests they need to keep the church going.

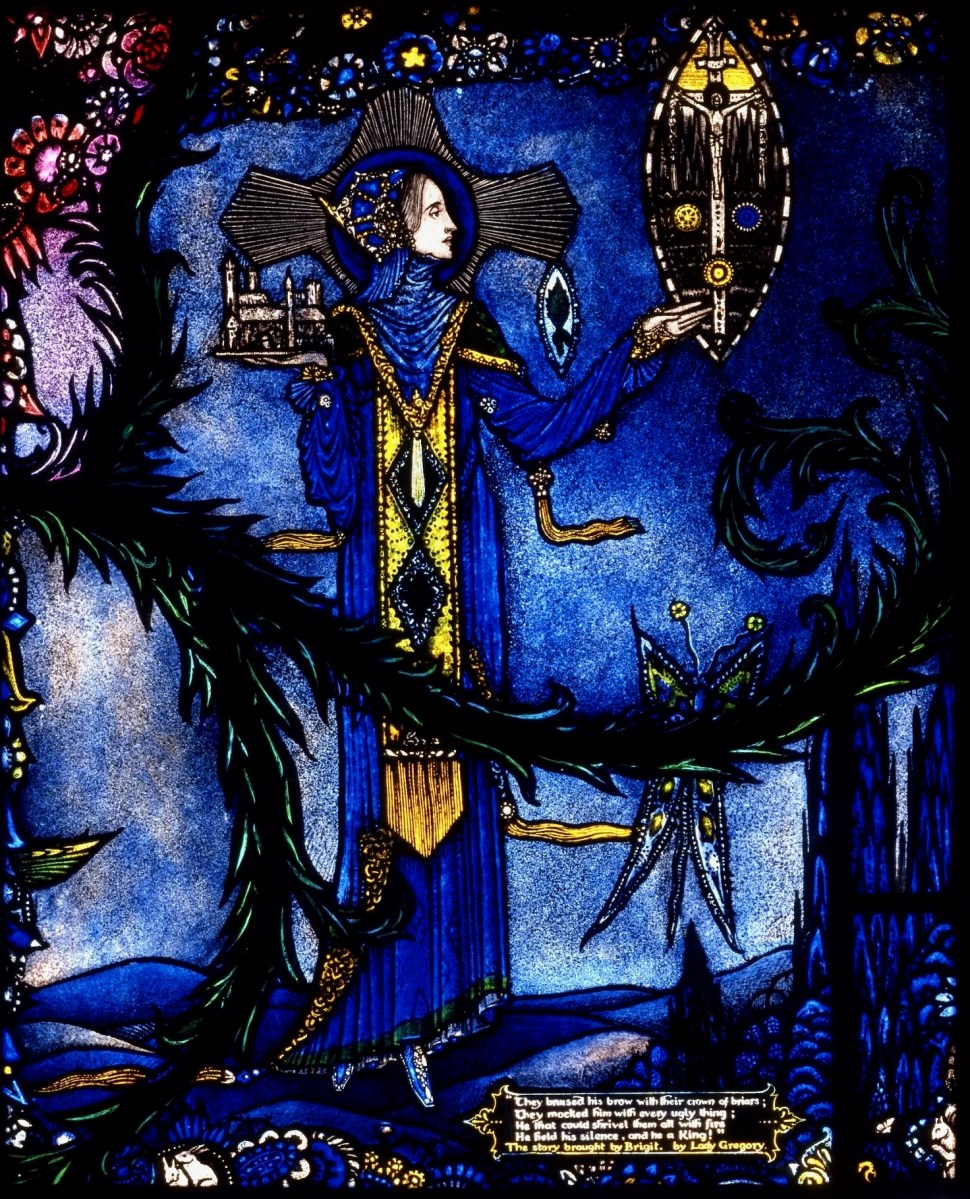

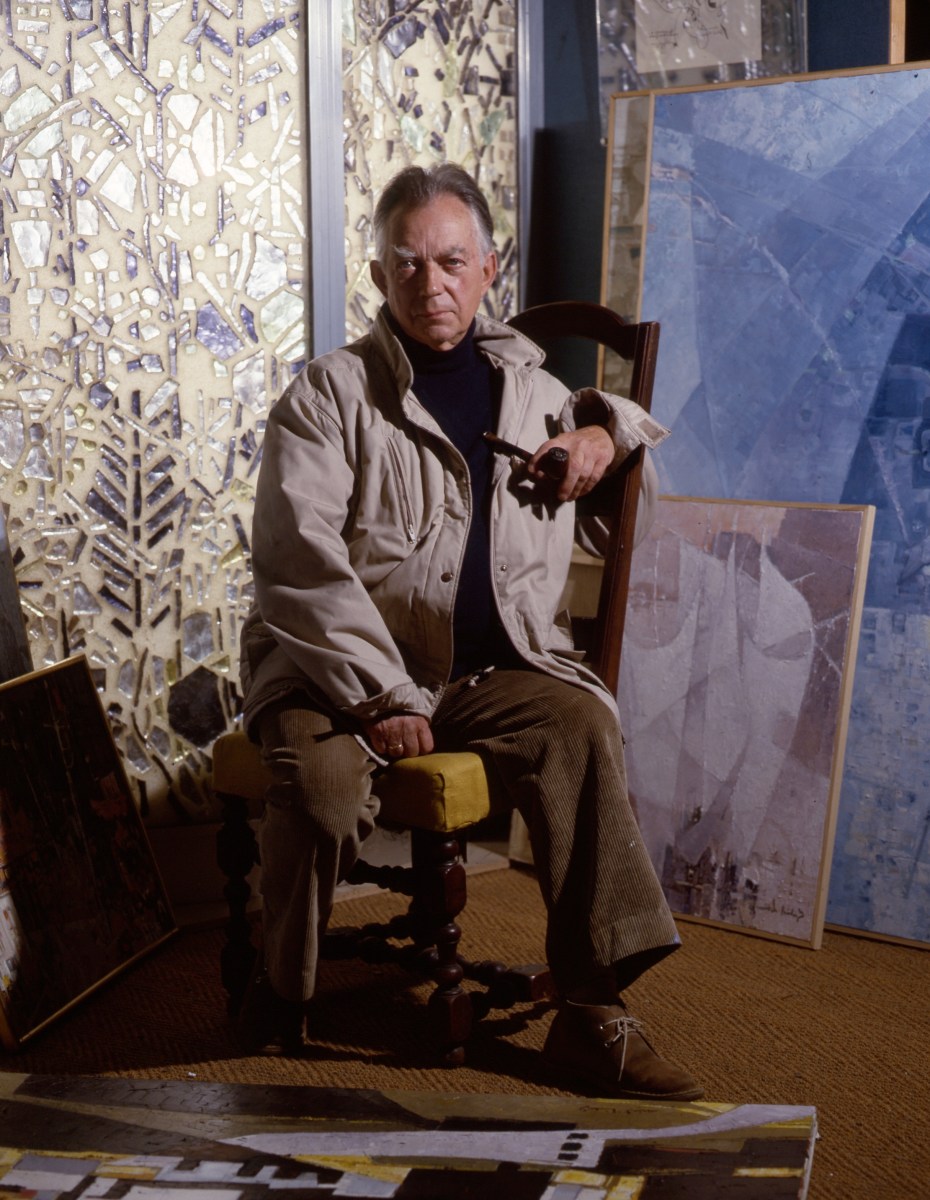

Why am I writing about the closing of a church in Cork? It’s because this is one of four buildings in Ireland (all churches) that contain the work of the internationally recognised dalle de verre master, Gabriel Loire, of Chartres in France (below). Let’s start with – what is dalle de verre?

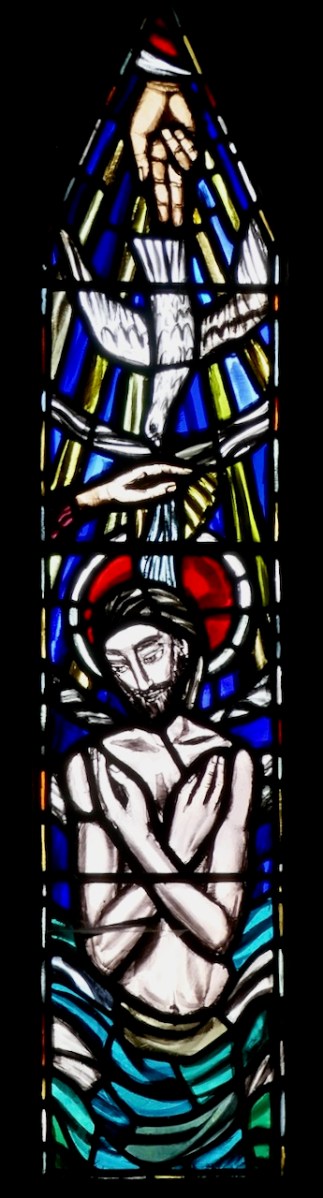

Dalle de verre, sometimes simply called slab glass, is a stained glass technique that uses thick slabs (dalles) of coloured glass, arranged to form patterns and embedded in concrete or resin. Each slab is faceted by knocking spalls off it with a hammer. This is the same technique, by the way, used by flint knappers to make prehistoric tools. Due to the nature of conchoidal fracture, the spalls come off in concentric ripples, enlivening the colour through the layering and refracting of the light coming through from the outside. You can see how dalle de verre is made in this video or alternately in this one (which made me smile with that Pathé voice).

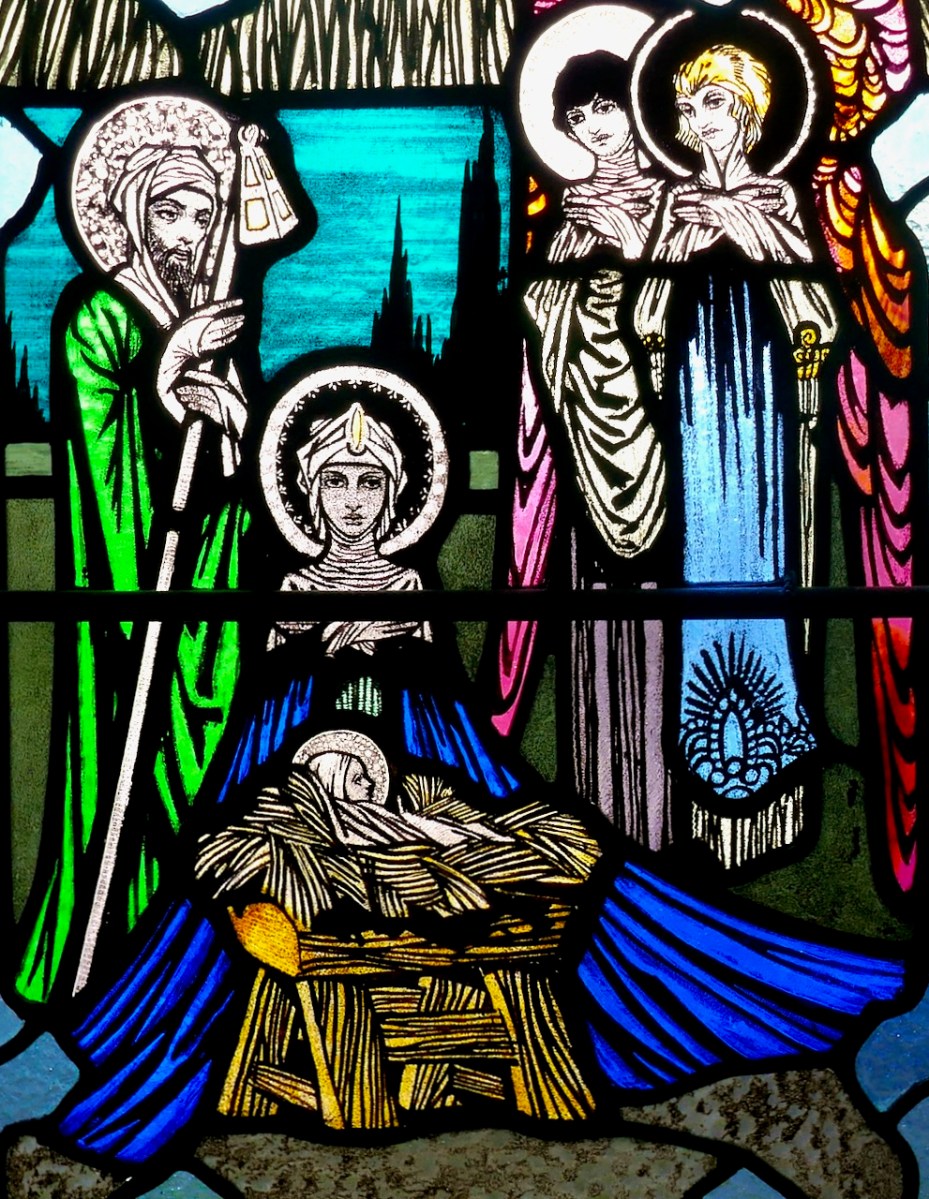

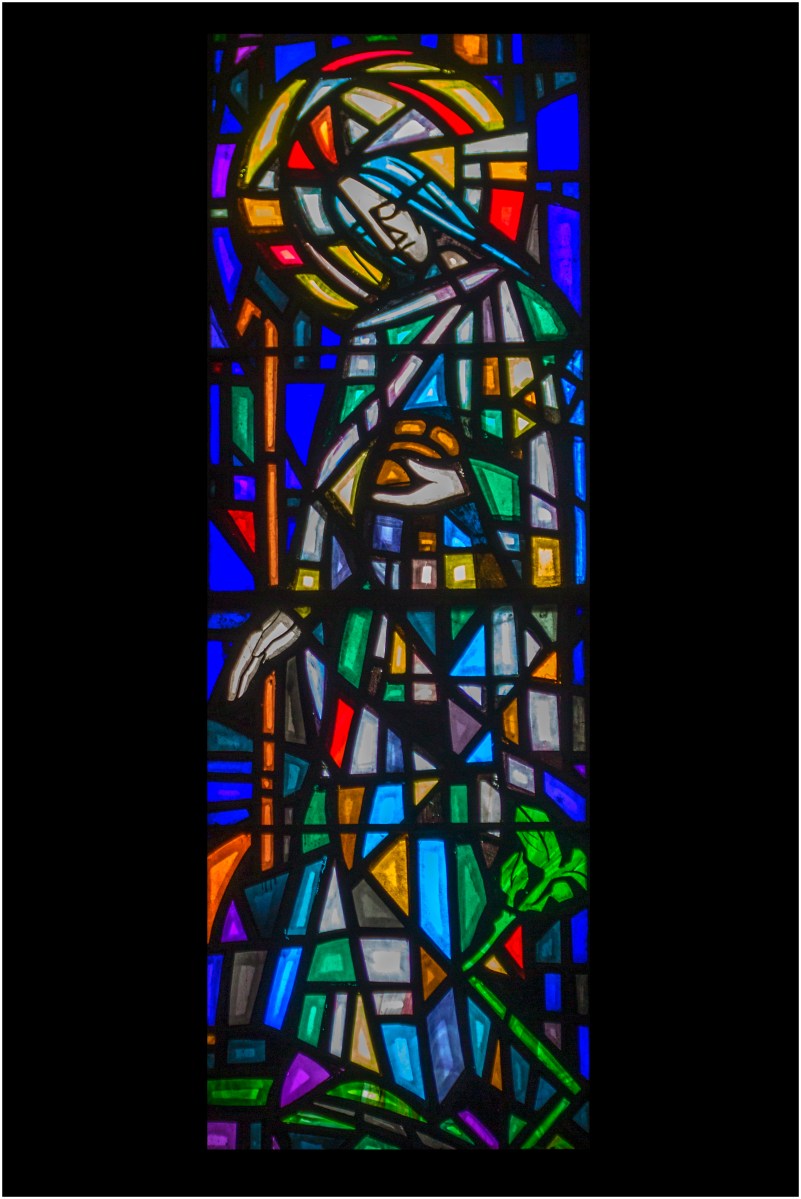

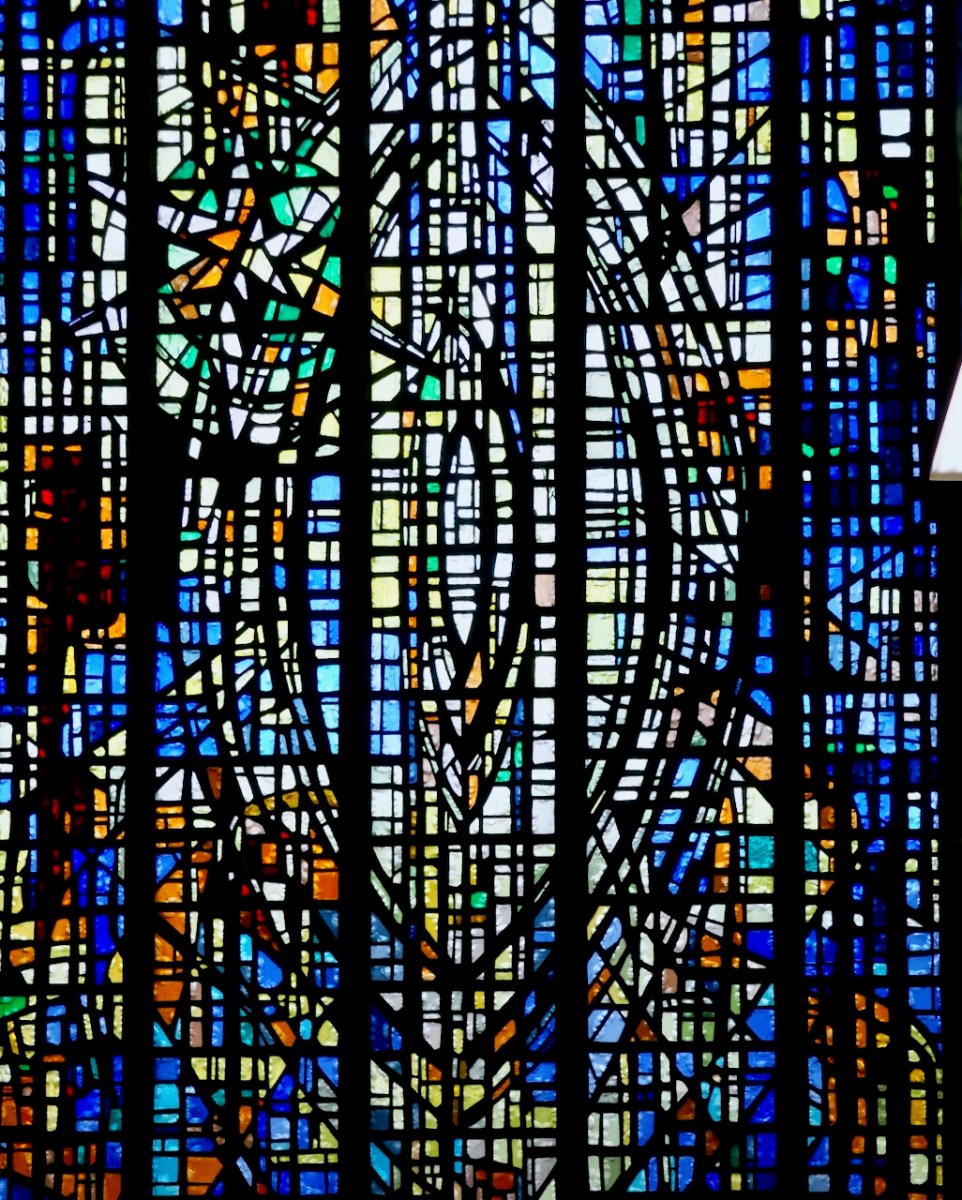

Figures and icons in dalle de verre windows are not normally painted as they would be in classic stained glass, but formed through the arrangement of the dalles and the cement lines. They are, by necessity, minimally detailed and windows are often non-figurative, relying on arrangements of colour and flow to suggest subject matter and create interest and atmosphere: thus, they also suited the mid-century artistic movements of abstraction and cubism.

The great advantage of dalle de verre is that it can be used as part of the integrated fabric of a building: that is, as a building material rather than a decorative detail. It lends itself to enormous expanses of glazing and to soaring verticality and this made it very attractive to twentieth century modernist architects. In Ireland several architects championed this new material and incorporated walls of dalle de verre in their churches from the 1960s on.

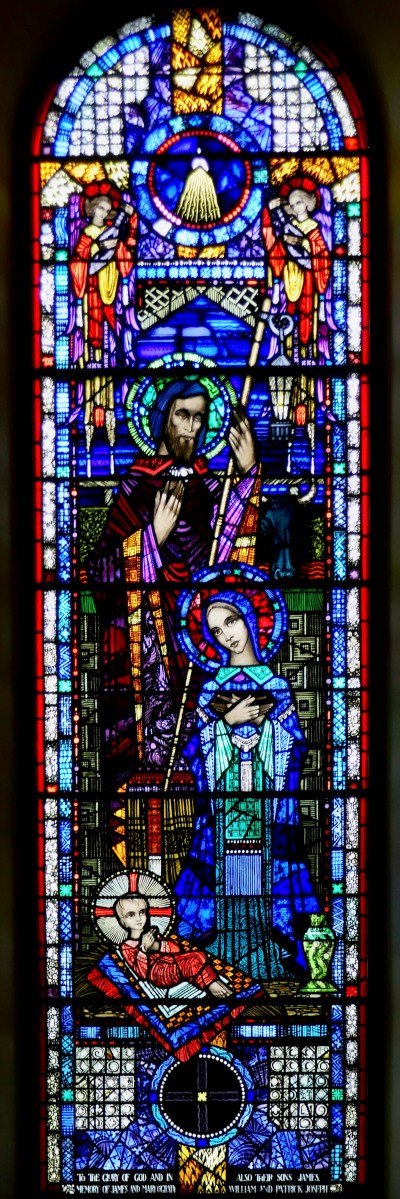

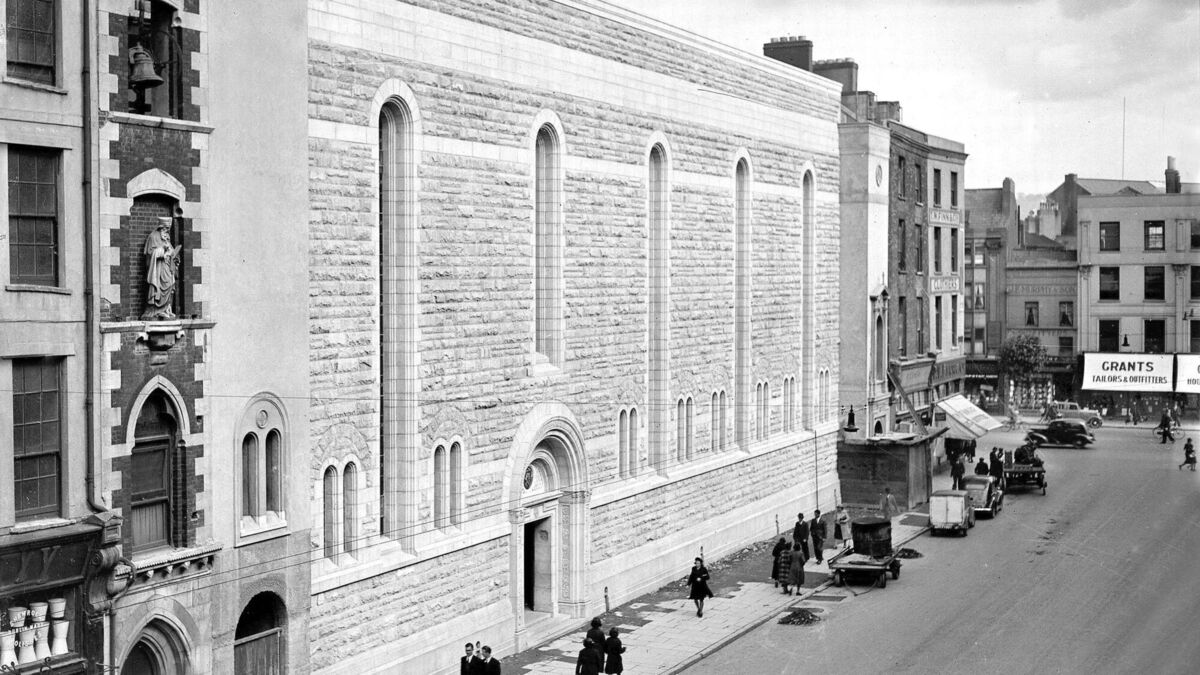

St Augustine’s church was designed by the Cork architect Dominic O’Connor and opened in 1942, on the site of a former church about which I can find no information. That’s what it looked like (above) when it opened (courtesy of the Echo). Thirty years later it was extended and refurbished (spot the difference!) and it was at this point, in 1971, under the supervision of the architect Patrick Whelan, that the Gabriel Loire windows were installed. Whelan turned to Gabriel Loire as the natural choice – not only was this his fourth (and final) Irish window, but by then he was acknowledged as the leading practitioner in the world of this art form.

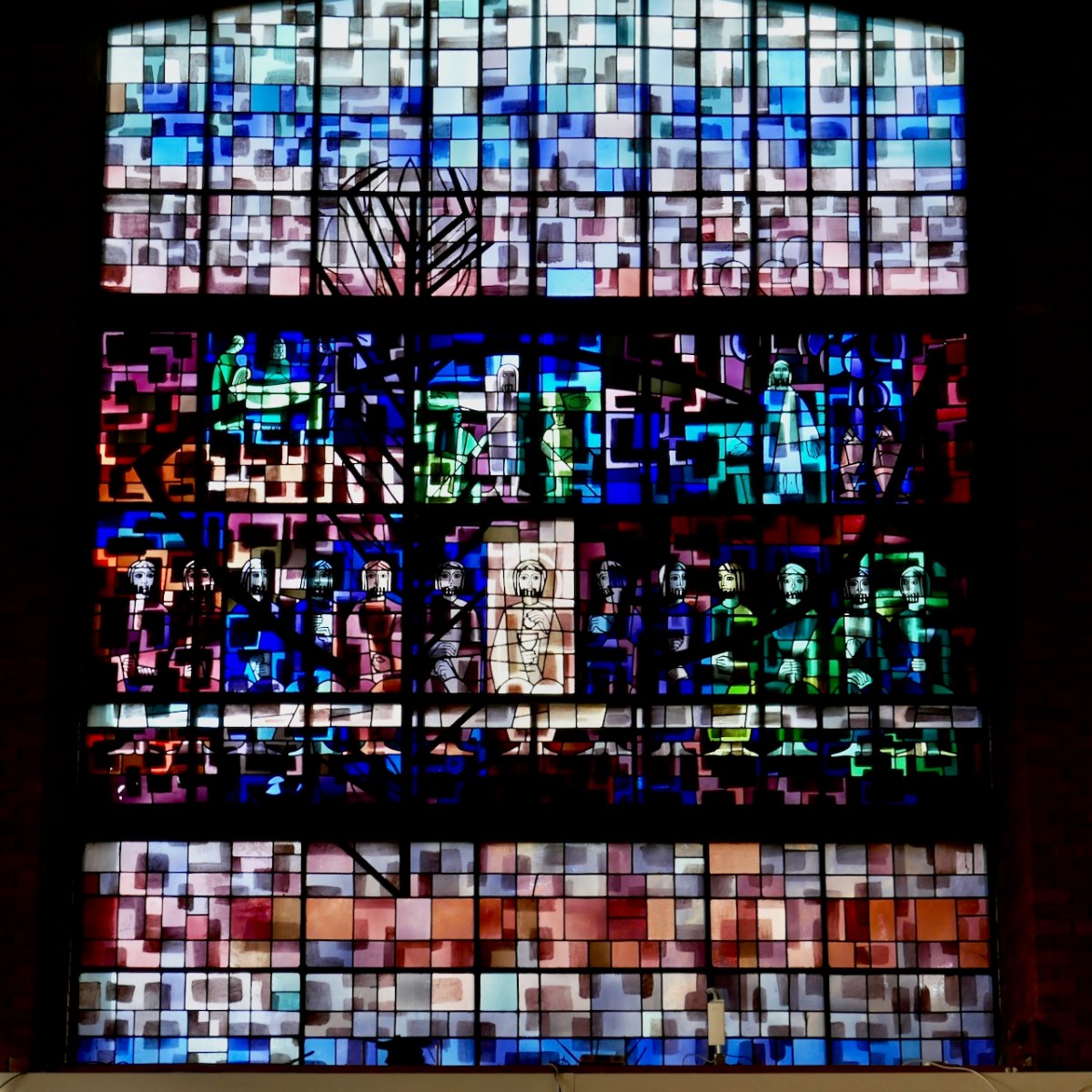

The windows are enormous, floor to ceiling. From the outside (thanks to Piotr Slotwinski for the image above) the form of the artwork can be clearly seen as a complex swirl of patterns, delineated by the concrete lines.

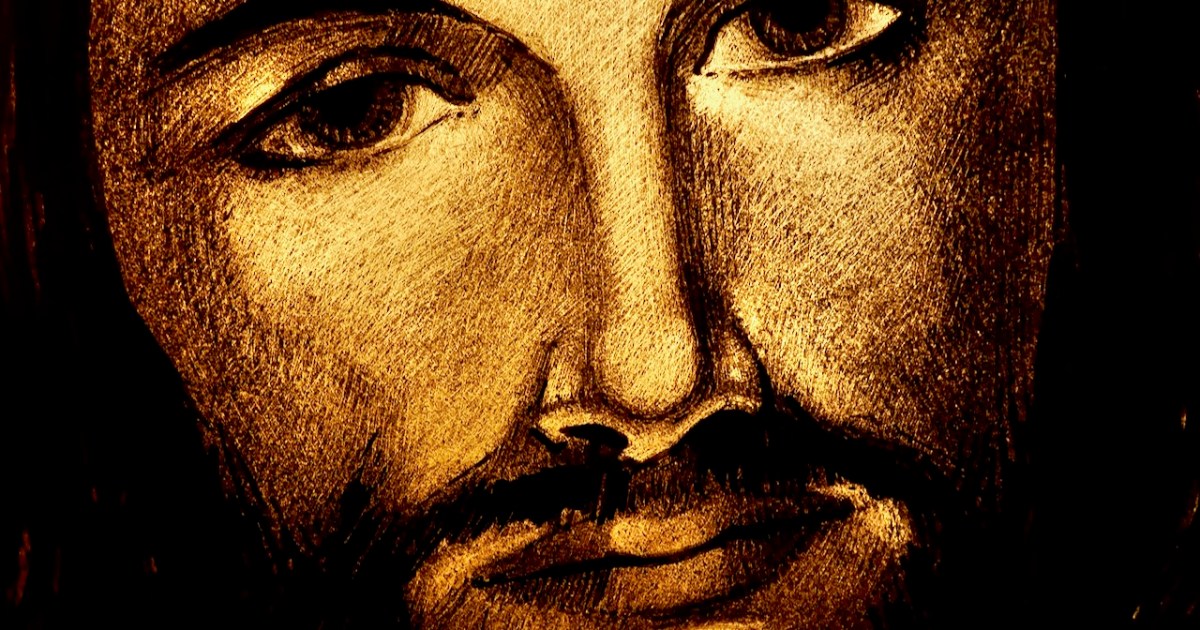

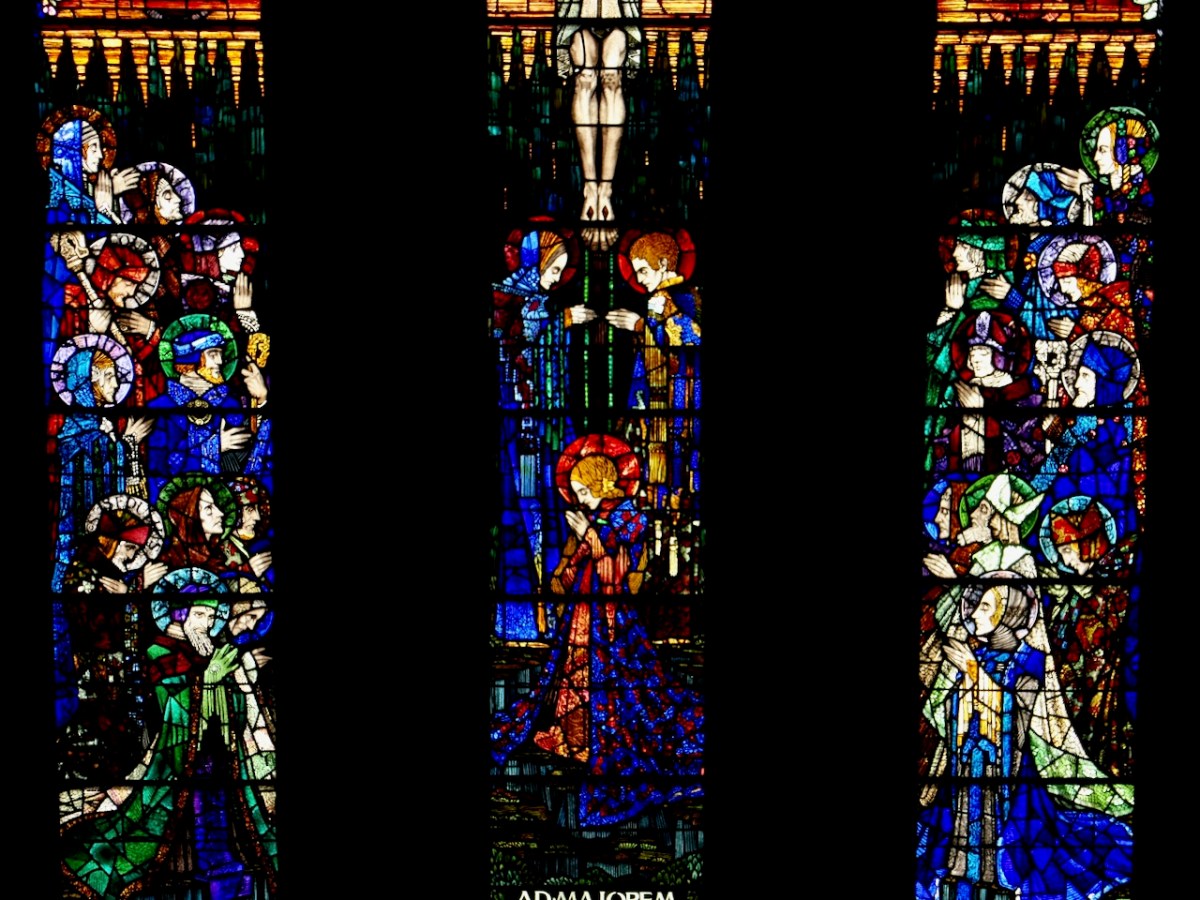

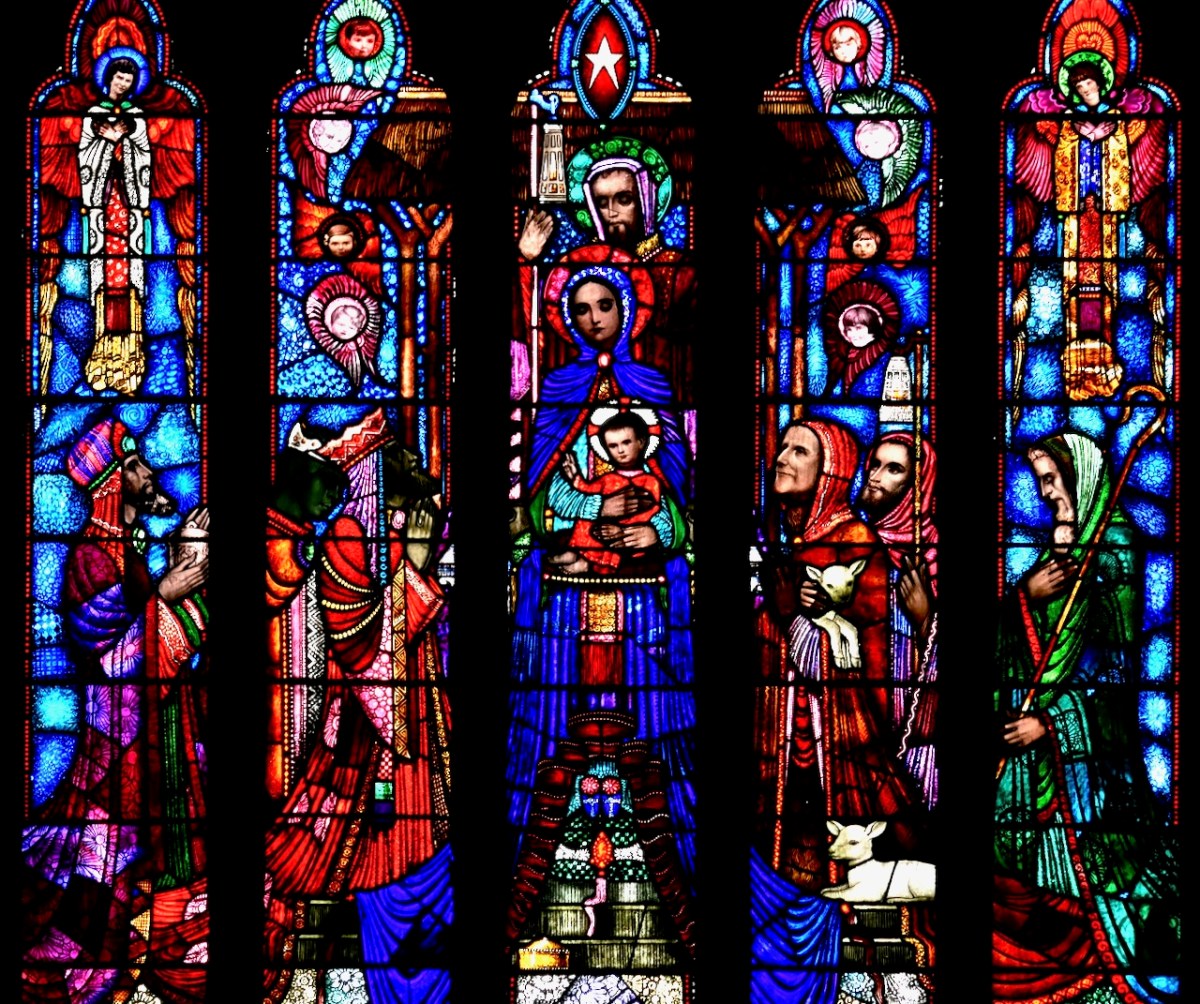

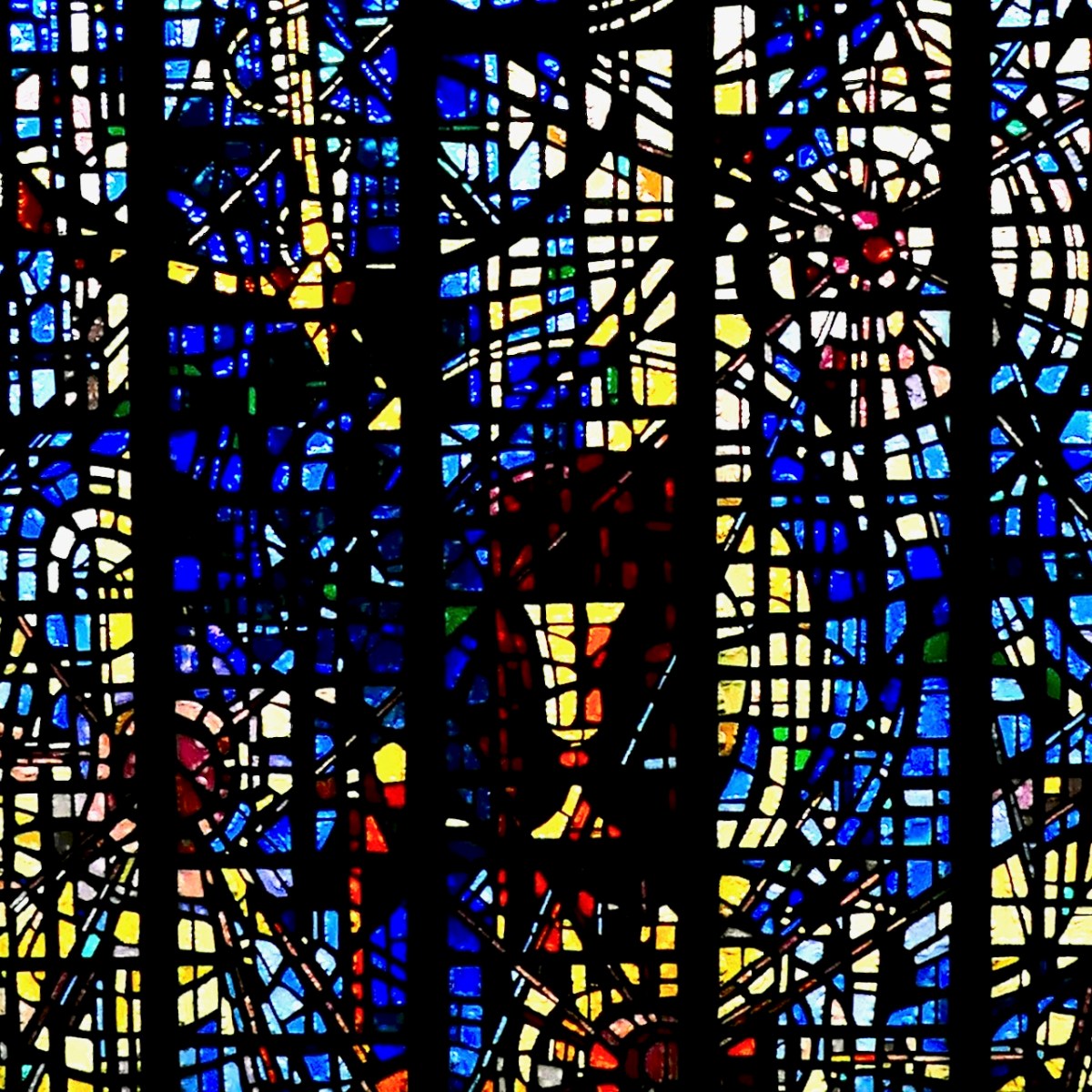

Inside, the two windows are across from each other on either side of the altar. To see them properly you have to go right up to the front. At first, they look pretty much as they do from outside – a complex swirl of patterns. You immediately notice the dominance of a rich blue – stained glass artists know this as Chartres Blue. It was a favourite of Harry Clarke, and of course of Gabriel Loire, whose atelier was in Chartres, in the shadow of the Cathedral. The actual iconography is hard to pick out at first, but obvious once you see it. The street (or south) side is the Eucharist window (above). An enormous chalice in shades of gold against a ruby red background occupies the bottom third of the window above the doors.

Various sunburst motifs fill out the window (see the feature image, the one above the heading). The sunburst — or solar radiance motif — has layered meanings in Christian iconography. At its most fundamental it represents Christ as The Light of the World but it also becomes a metaphor for divine presence, grace, and the Transfiguration. The only other recognisable icon is an anchor. The anchor also functions as a cross around which a rope winds – a traditional image meant to convey that Christ is our anchor, but which could also be an homage to Cork’s great maritime heritage.

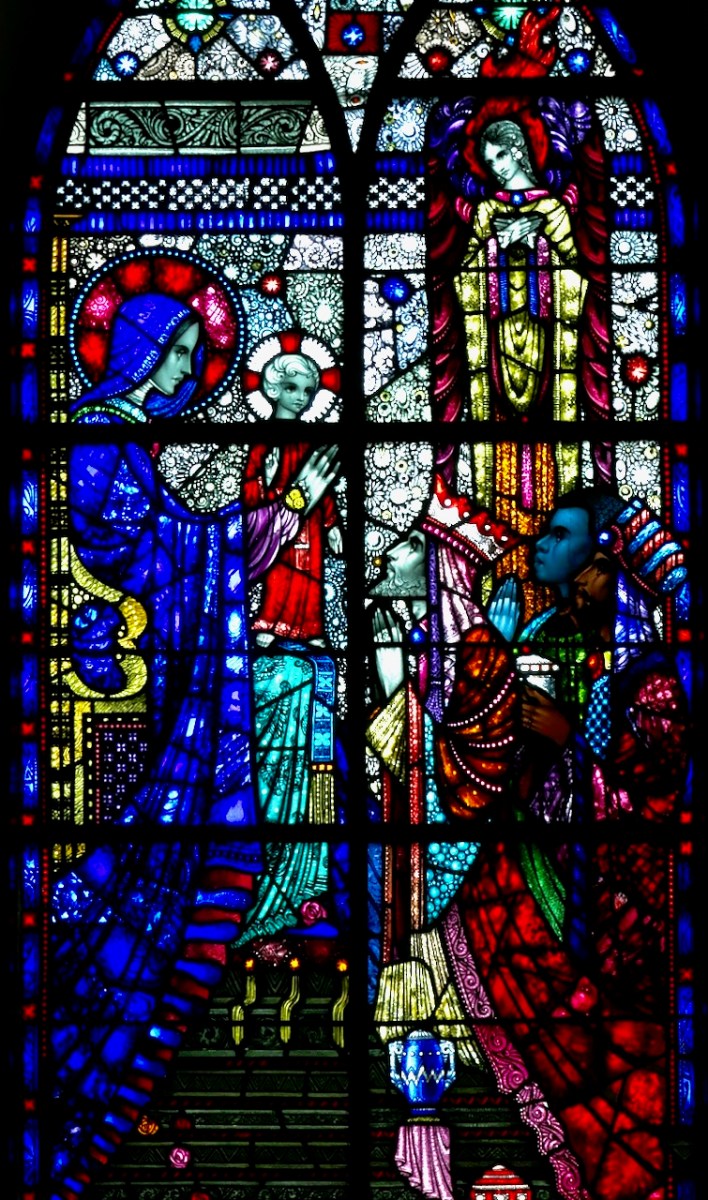

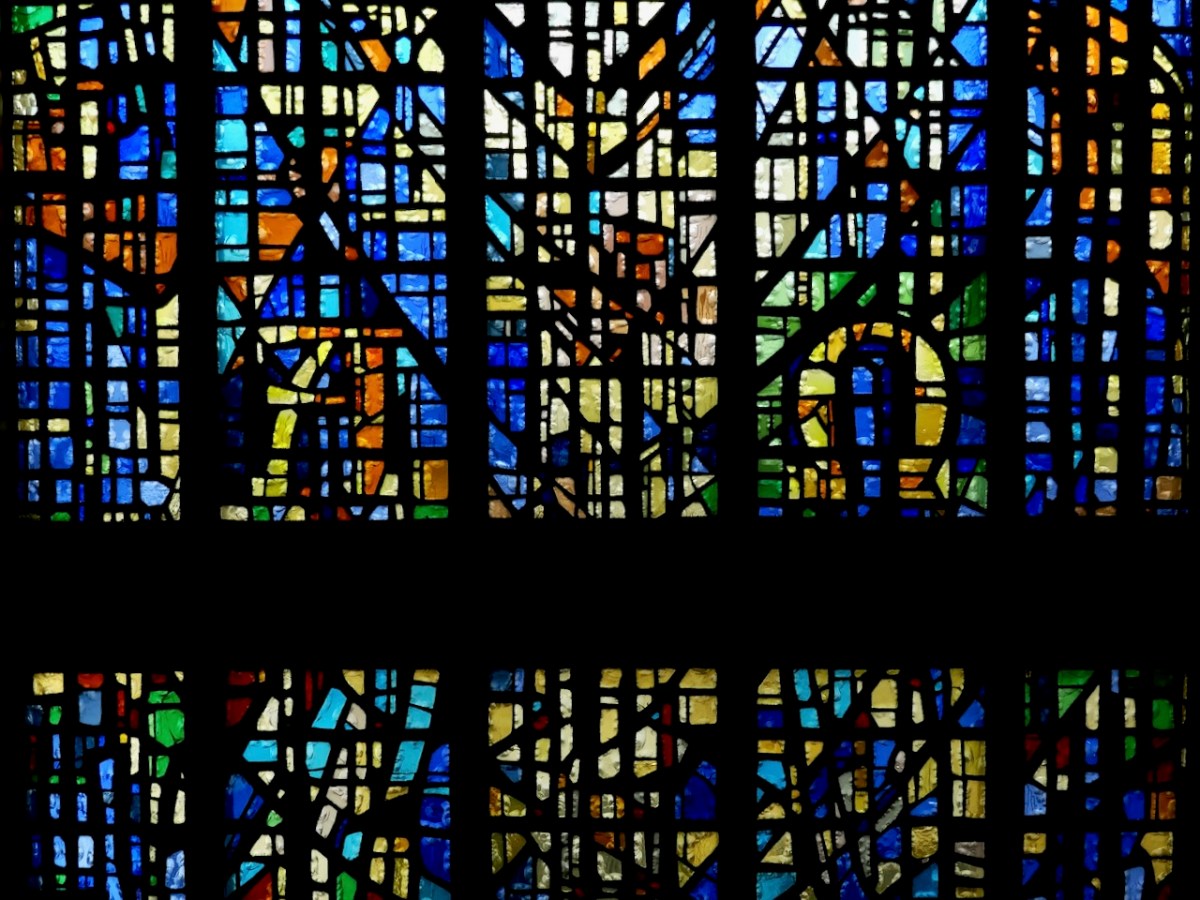

The north side window is the Alpha and Omega window. The Alpha and Omega symbols are clear, and above them is an enormous mandorla, which takes up most of the window. There is also a star (my lead image at the top of the post under the heading) – indicating a contrasting nighttime theme across from the sunburst of the south window. The mandorla in Christian iconography is highly significant. It is the form used to frame Christ in Majesty and also the Virgin in Glory. Taken together with the Alpha and Omega, this window can be interpreted as concerned with Christ as beginning and end, first and last, the eternal sovereign.

That’s actually a very deliberate and sophisticated arrangement – the altar sits between the two windows, with the congregation facing west. Thus, one could see it as the celebrant and congregation being held between the Eucharistic presence (south) and the cosmic Christ in Majesty (north). In this reading, the windows are doing active liturgical and theological work in relation to the altar and the gathered community.

The architect, Patrick Whelan, (that’s him below with Des O’Malley) was working in the post-Vatican II era which set off a renaissance in how art and architecture was to come together to modernise the liturgy and glorify God. It is obvious he thought carefully about the integration of art and architecture, resulting in a unified modernist sacred space, not just an extension with some windows added. In this, he had the perfect collaborator in Gabriel Loire.

If St Augustine’s is lost (and I have no idea what is to happen to it) we are losing a coherent ensemble where architecture, liturgical arrangement, and art were conceived together, very much the spirit of the post-Vatican II liturgical reform movement. The altar brought forward, the community gathered around it, art serving the liturgy rather than decorating the walls: Loire and Whelan were clearly working in that spirit. The closure of the church therefore represents not just the loss of two windows but the loss of a complete and largely intact example of that mid-century liturgical vision.

I said at the beginning that this was one of four Gabriel Loire Churches in Ireland. Next week I will show you the others, and say a little more about dalle de verre – its advantages for architecture and what led to its ultimate decline.