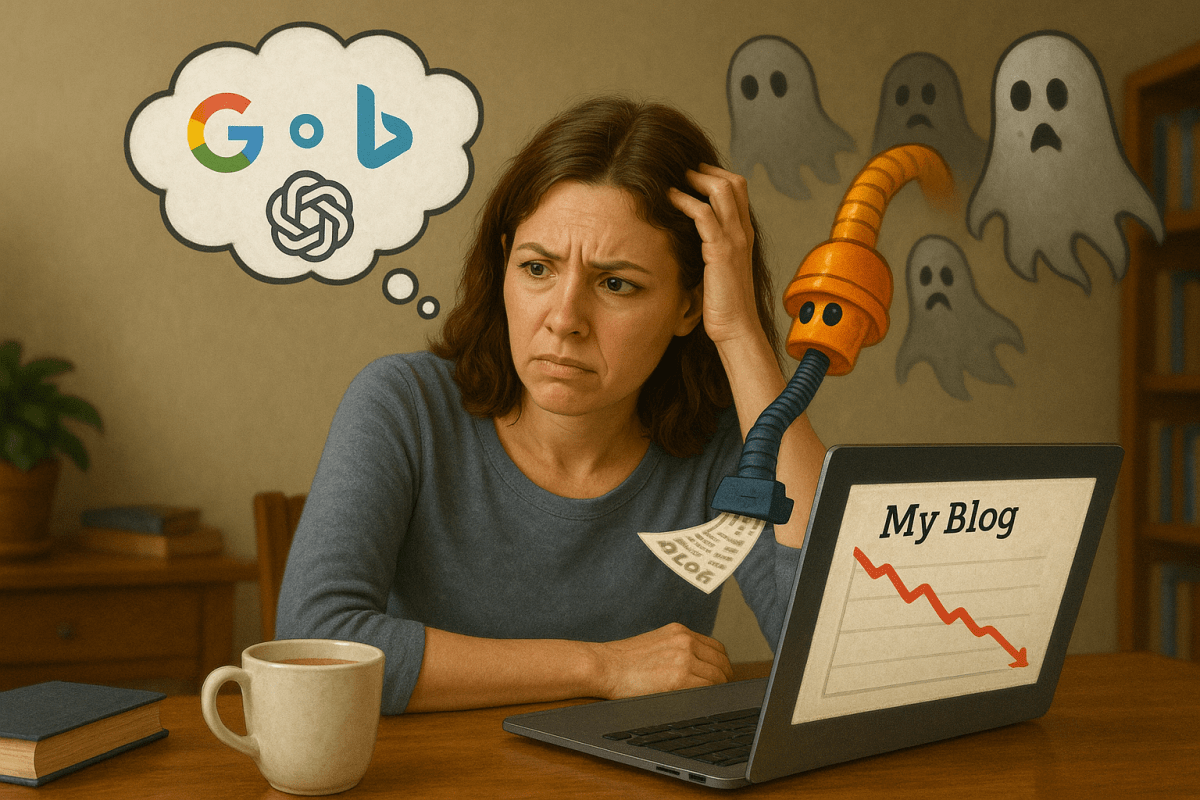

AI is a double-edged sword and the future for Roaringwater Journal, and blogs like it, is looking grim.

First, the not-so-bad news.

I’ve made no secret of the fact that I have been exploring various AI tools – chatbots and search engines and research tools like NotebookLM. My first foray was when I asked ChatGPT to write an 800 word essay on the history of West Cork. Although a cursory read left an impression that was persuasive, in fact it was riddled with errors. That was in 2023. Today I asked it to do the same again and I append the results below. MUCH better and in fact this time very accurate.

I’ve also used image-generation software – I had fun with a St Brigid Post a while back – the results, although amusing, were a mixed bag – I’d say this aspect of AI has a lot of catching up to do.

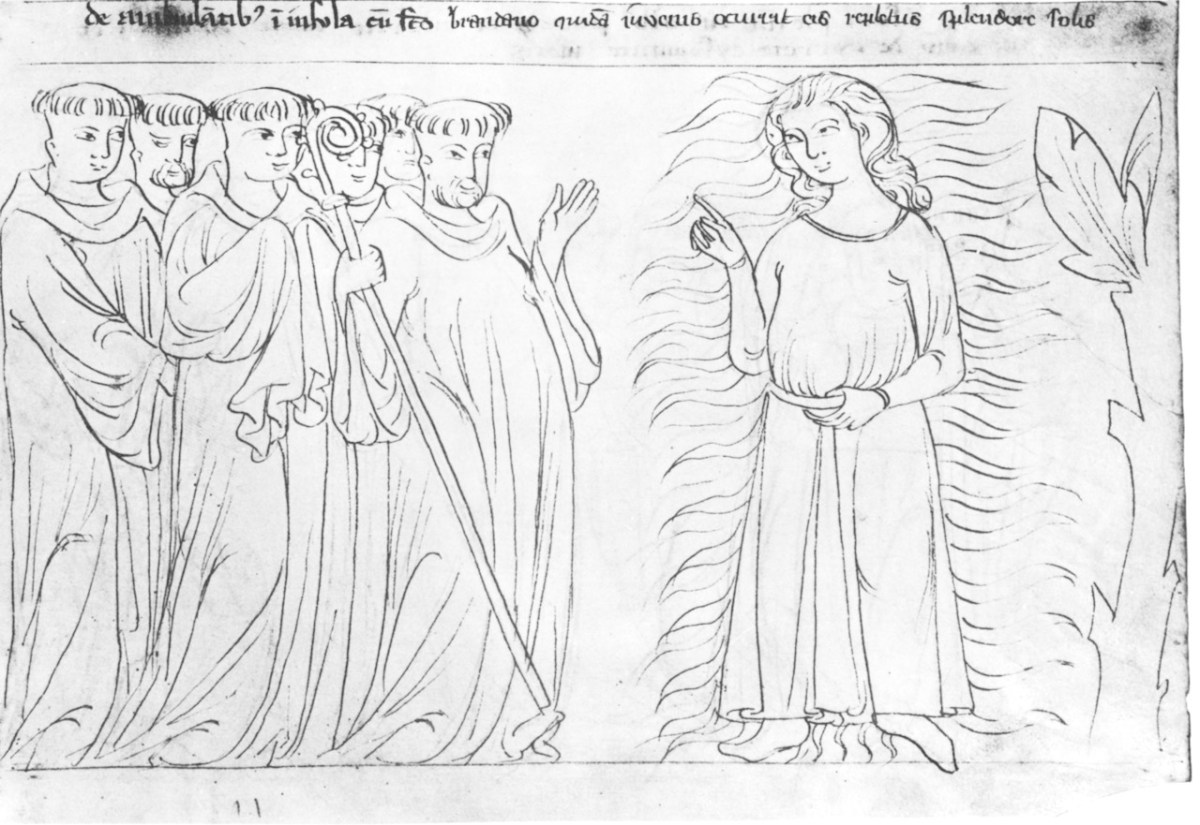

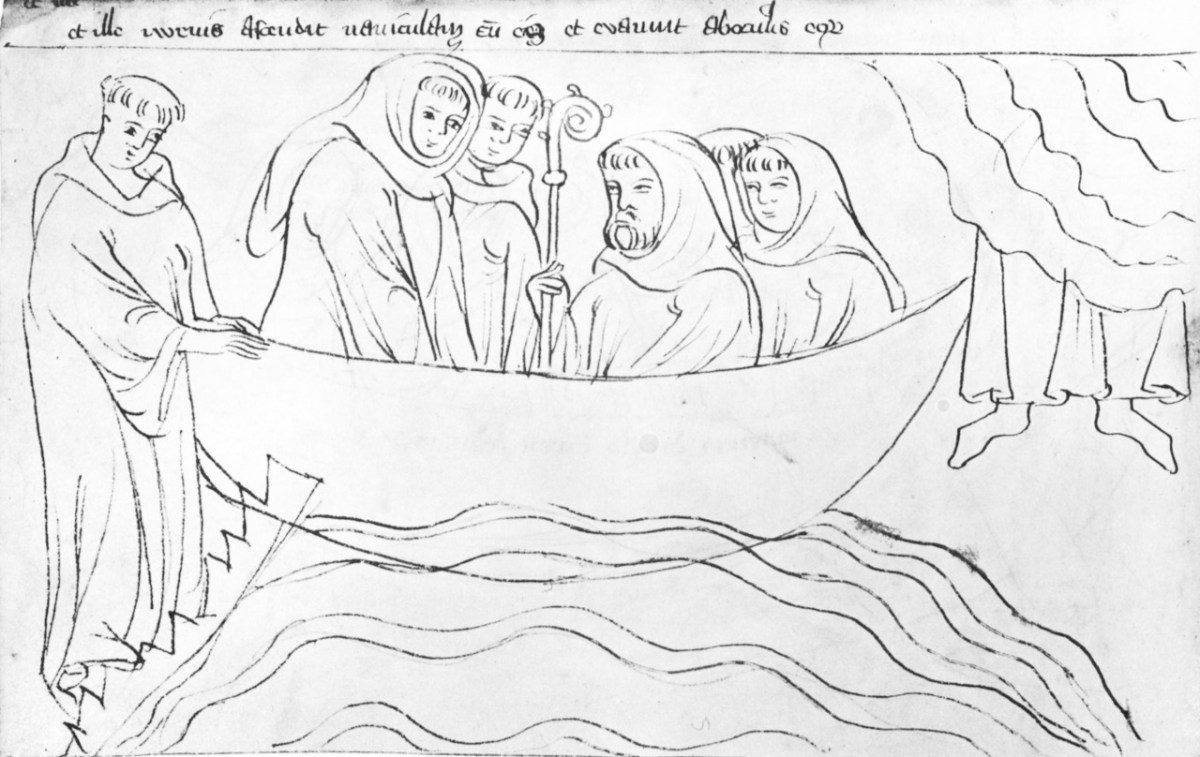

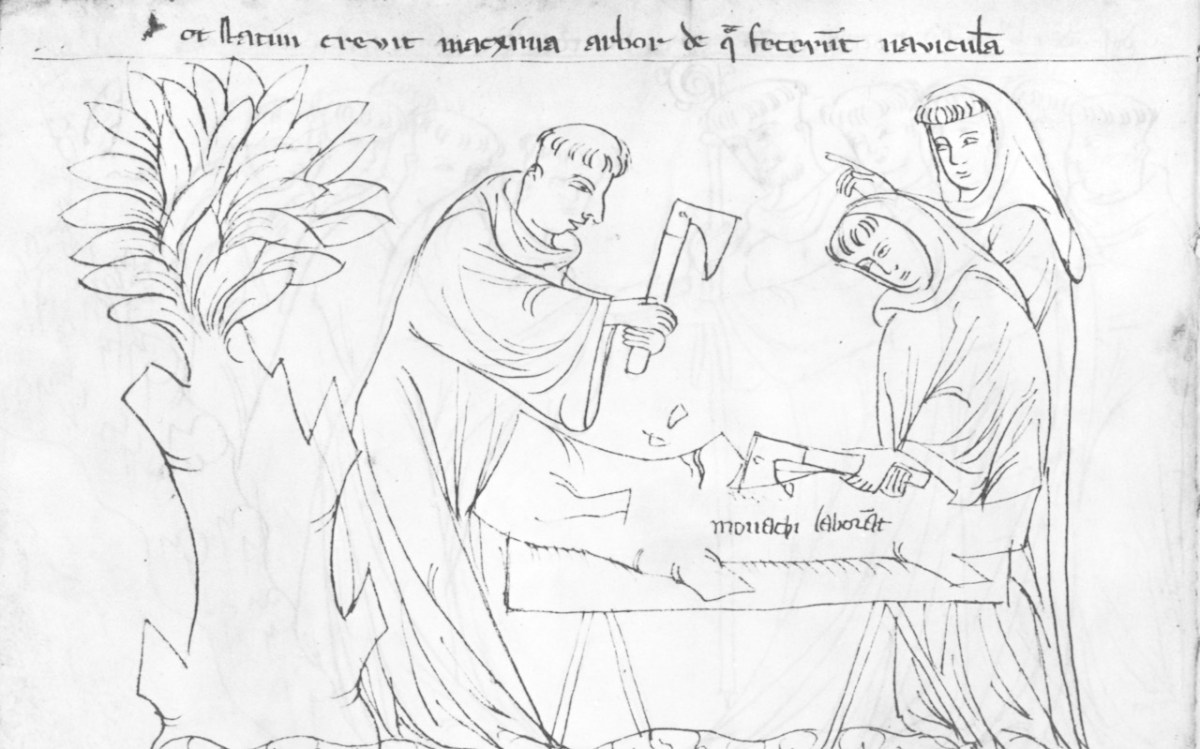

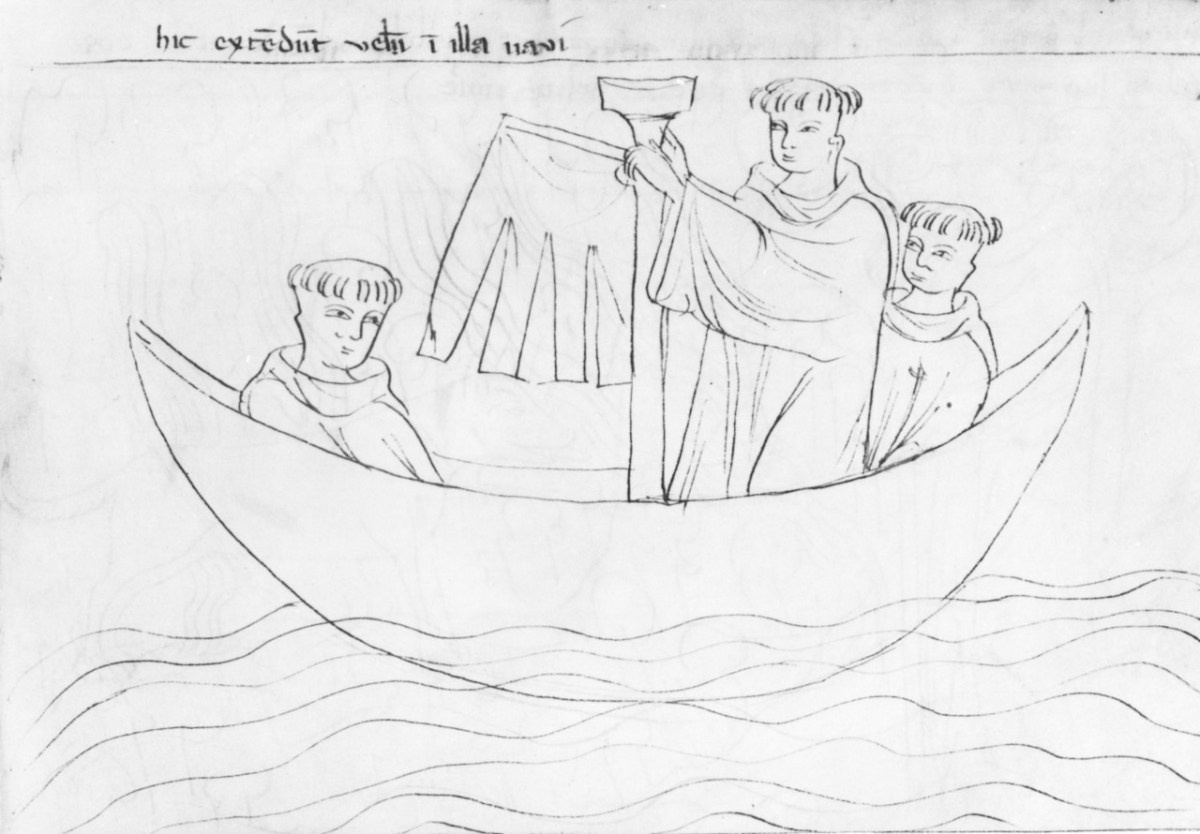

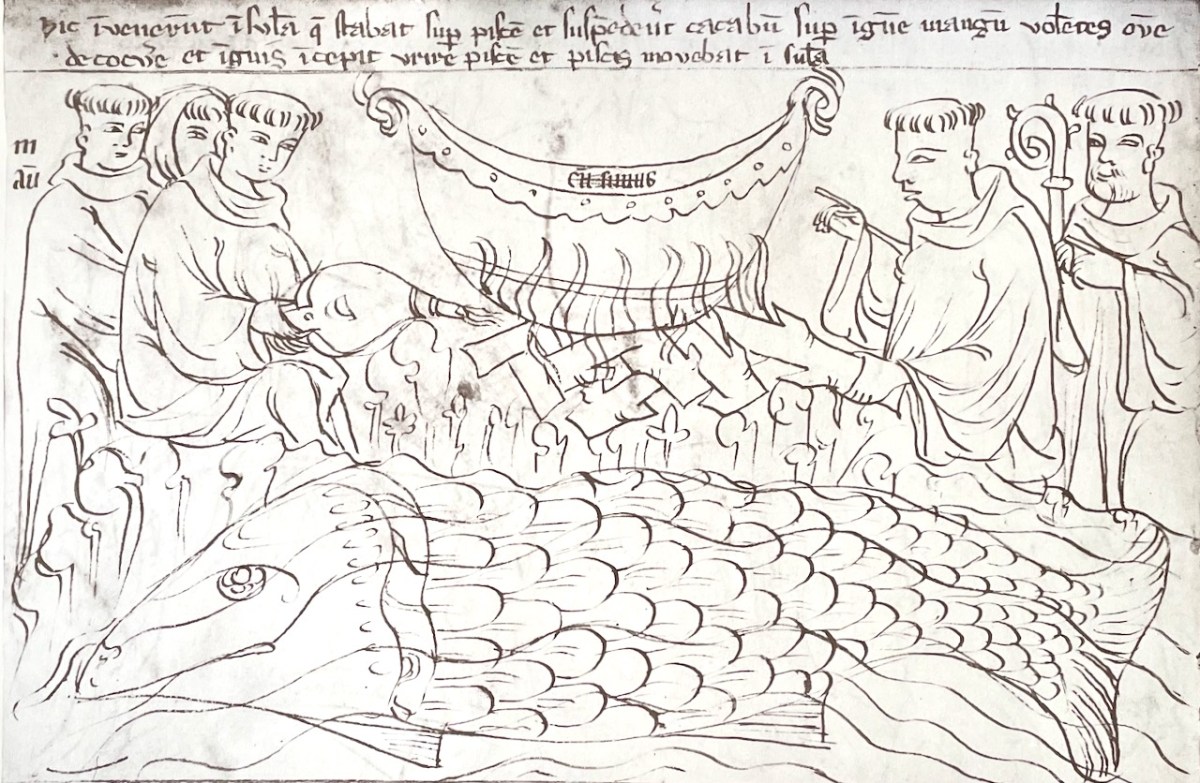

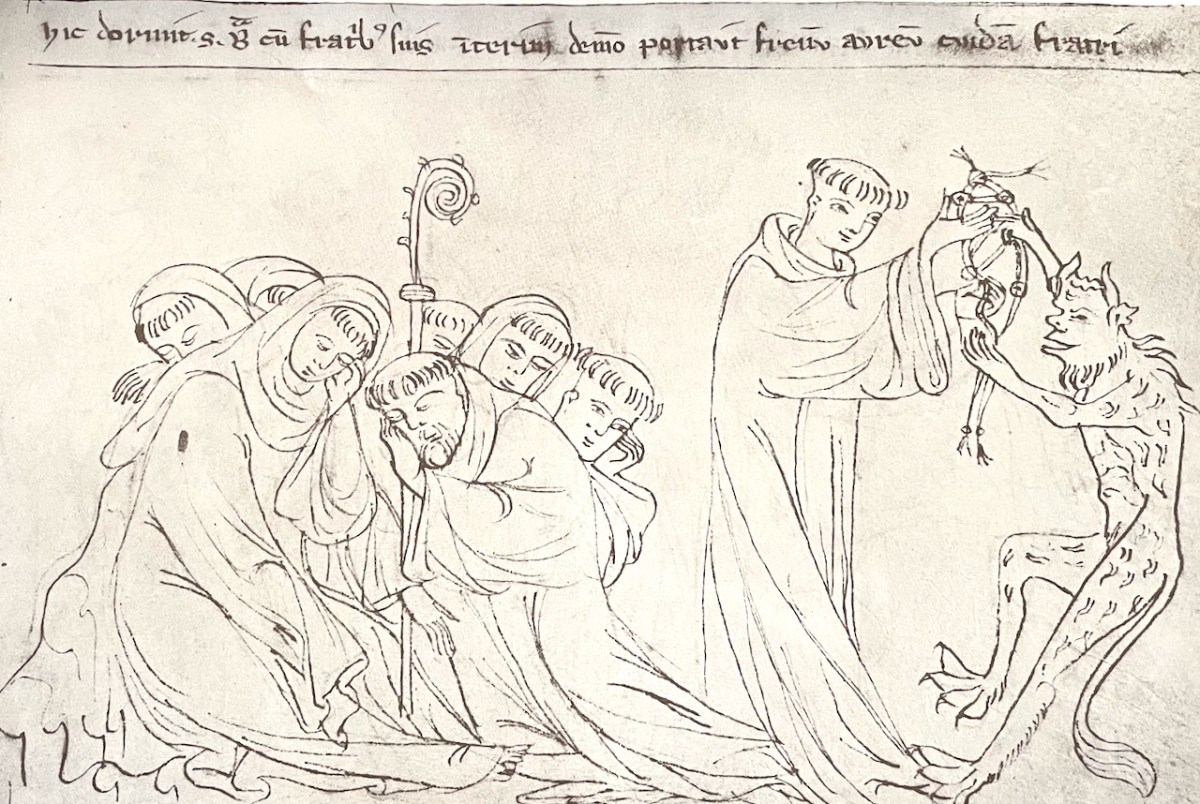

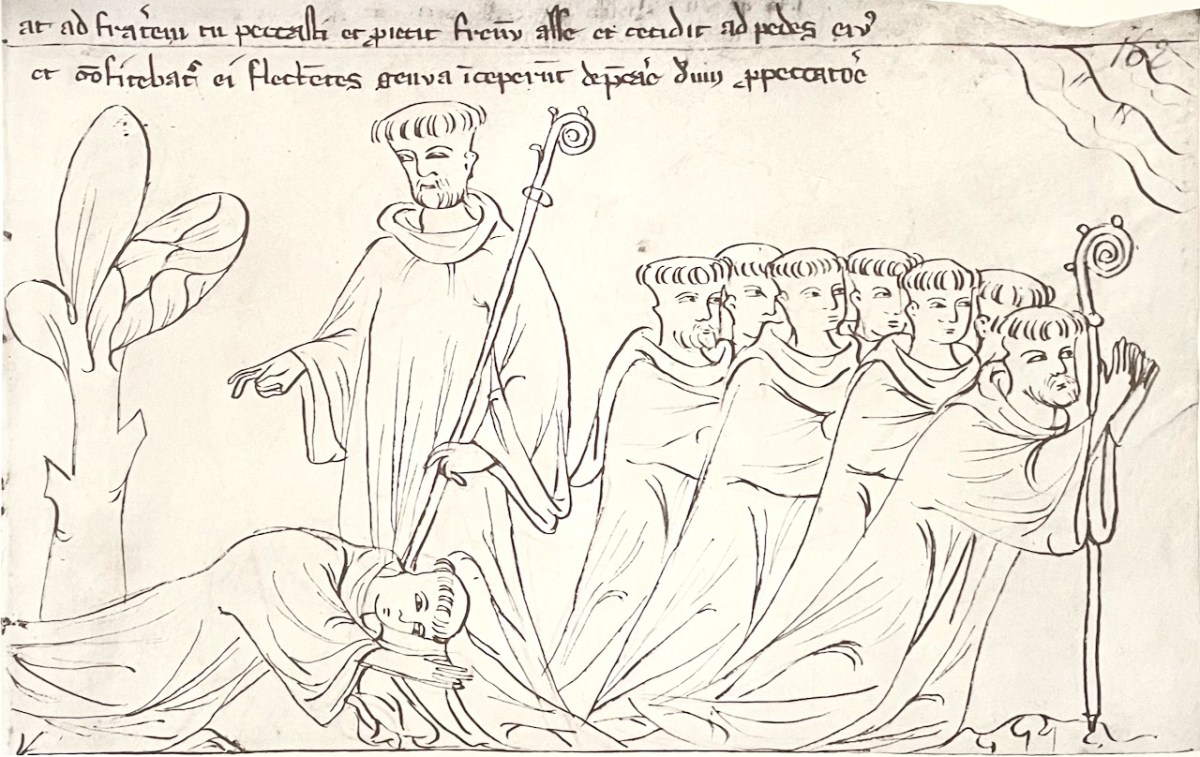

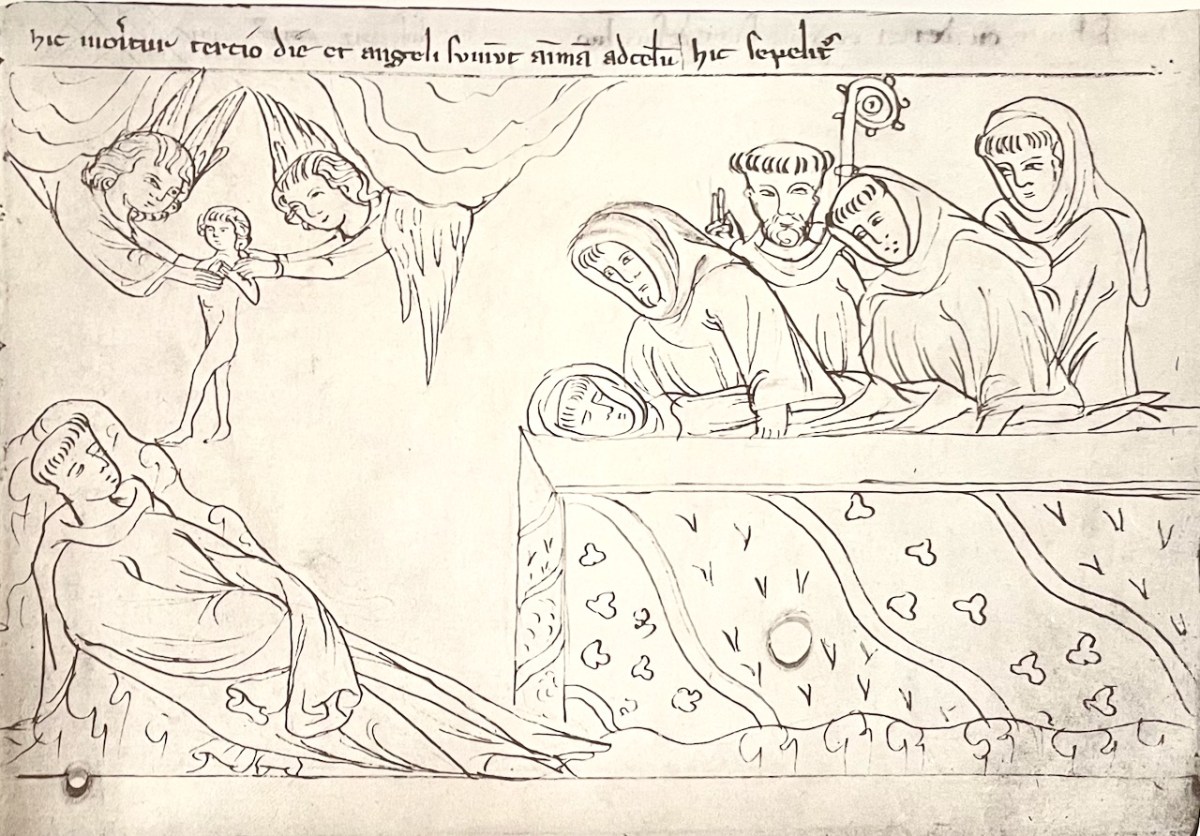

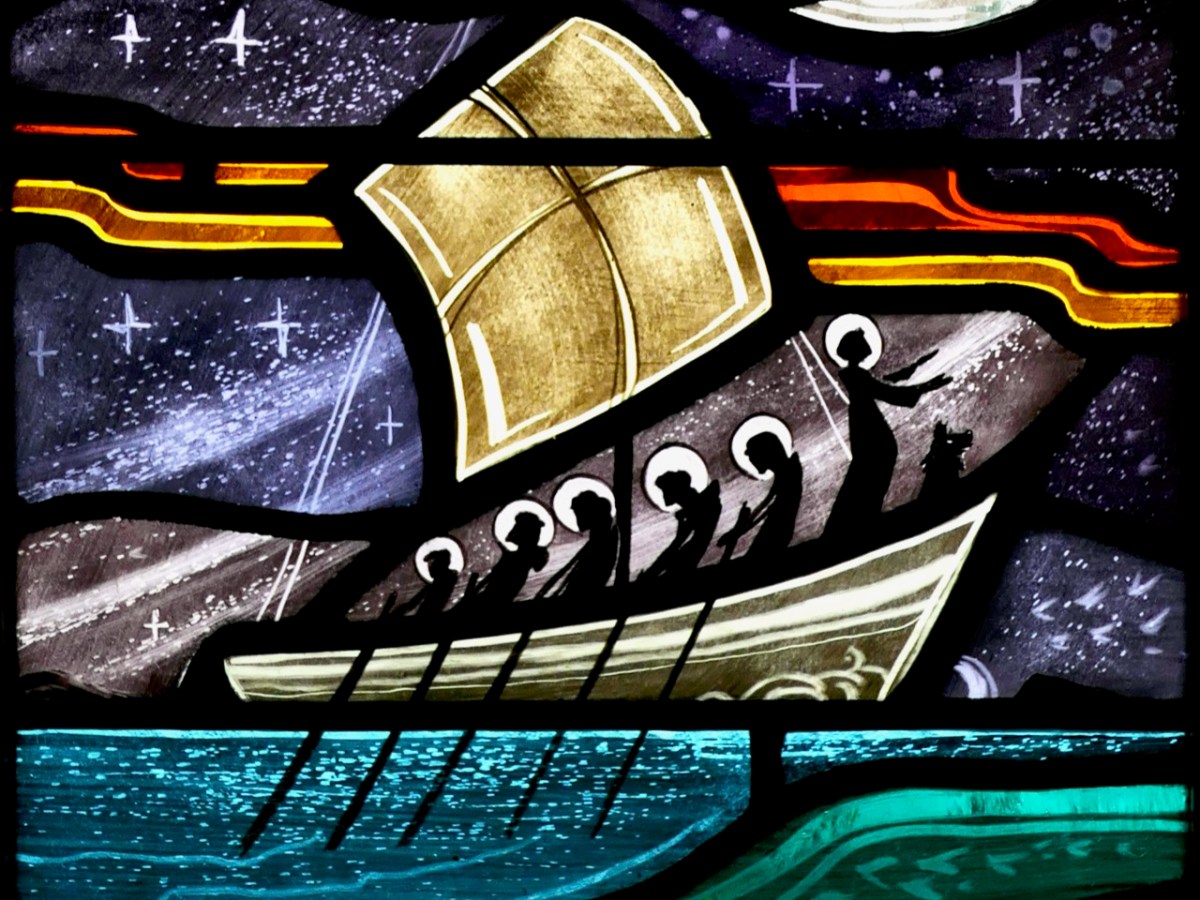

I also used Perplexity as a research assistant on my recent series (2 down, 1 to go) on the St Brendan book I purchased, which was written in German.

Finally, I used NotebookLM to keep track of all my references when I did the series on Charles Vallancey. NotebookLM is an excellent research tool which uses the sources you upload yourself. I had 15 different sources for this series, mostly lengthy academic articles, and I was able to use NotebookLM to tease out threads across the articles, each statement referenced back to its source.

Now for the other side of the coin.

When you did a Google search in the past, it came up with a list of Blue Links – clicking on a link brought you to the source website. Search engines drove a lot of traffic to our website.

If you do a search now, the first thing you are likely to see is what’s called an AI Overview. Although there are still links (for now) to Roaringwater Journal and other local sites, many people just read the AI Overview and go no further. If you use ChatGPT the information will simply be served up to you in a condensed form, with no link to sources or to further information.

Perplexity includes links in the form of tiny numbers at the end of paragraphs which you may or may not notice or click on. Claude does something similar but seems to get most of its information from Wikipedia.

The AI companies have drag-netted the internet to train their Large Language Models (LLMs). Where information is scraped from Roaringwater Journal, it has happened without my knowledge or consent. This was not a problem in the past – Google gathered the information, but drove the searcher back to Roaringwater Journal – ‘click on this blue link for more information.’ Now, all my hard work and careful research is simply fodder for huge search engines who present it as if it’s their own. This is even more of an issue for bloggers who rely on traffic to generate income (I do not).

While traffic to the Journal (people landing on pages and actually reading what we have written) is a significant incentive to keep at it, it’s not the be-all-and-end-all for me, as I have all kind of other motivations for writing it. However, if the trend continues downwards, I can see myself and others taking stock at some point and wondering whether all our hard work is simply now providing content to enrich a bunch of tech-bro gazillionaires.

The ultimate irony? My story image was generated by ChatGPT!

I would value your comments.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

The History of West Cork: A Story of Resilience, Rebellion, and Rich Culture

West Cork, the southwestern region of County Cork in Ireland, is a landscape of rugged coastlines, rolling hills, ancient stone forts, and vibrant villages. Though often celebrated today for its natural beauty and bohemian charm, West Cork’s history is layered with tales of prehistoric settlers, Gaelic chieftains, Norman invaders, rebellions, famines, and a profound cultural resilience that still defines the area. The history of West Cork is, in many ways, a microcosm of Ireland’s wider historical experience—marked by both hardship and heroism.

Prehistoric and Early Settlements

The earliest traces of human habitation in West Cork date back over 6,000 years, to the Neolithic period. Megalithic tombs, stone circles, and standing stones—such as those found in Drombeg near Glandore—attest to the ritual and communal life of these early settlers. The Bronze Age (c. 2500–500 BCE) and Iron Age (c. 500 BCE–400 CE) left their mark in the form of wedge tombs, fulacht fiadh (ancient cooking sites), and ring forts, which still dot the countryside.

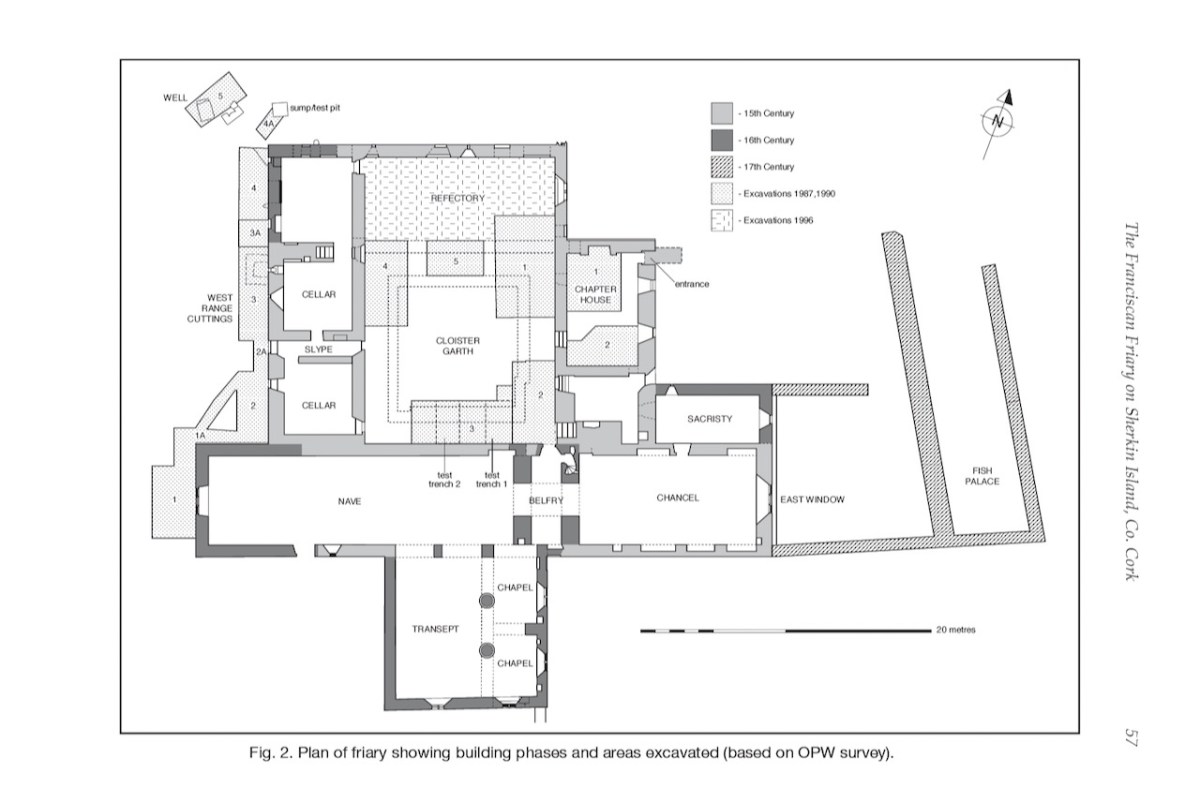

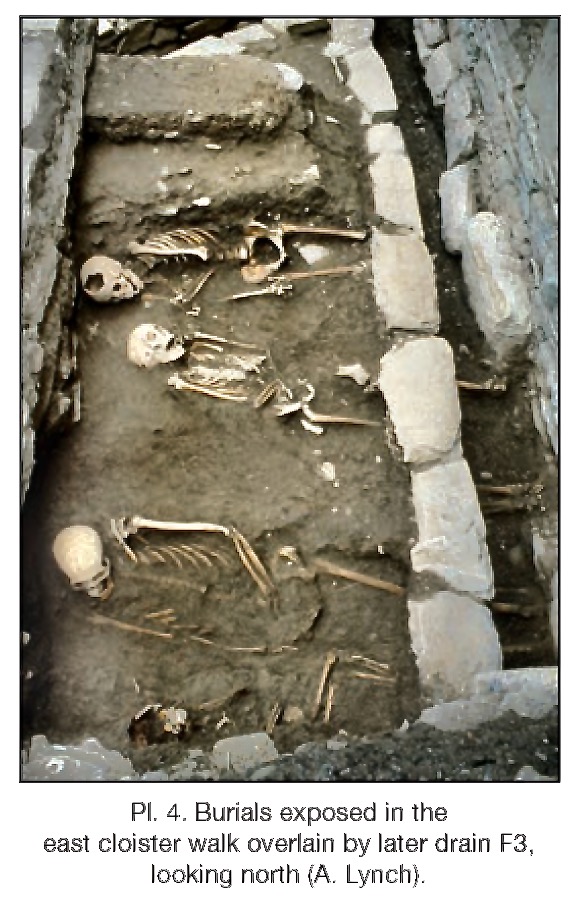

By the early medieval period, West Cork was part of the powerful kingdom of the Eóganachta, a Gaelic dynasty that ruled much of southern Ireland. The area was divided among local chieftains, with clans such as the O’Driscolls, O’Mahonys, and O’Donovans holding sway. These families established fortified homes and controlled trade routes, especially around the coast. The influence of Christianity also spread during this period, and monastic sites such as Timoleague Abbey were founded, becoming centers of learning and religious life.

Viking and Norman Incursions

Beginning in the late 8th century, Viking raiders arrived along Ireland’s coasts, including the bays and inlets of West Cork. Though initially destructive, the Vikings eventually integrated into Irish society, intermarrying and establishing trading posts.

In the late 12th century, the Anglo-Normans began their invasion of Ireland. West Cork, with its remote and rugged terrain, resisted complete conquest for some time, but eventually Norman influence took root. Towns such as Bandon and Kinsale (just on the border of what is traditionally considered West Cork) grew under Norman control. These new settlers introduced stone castles, new agricultural practices, and English legal structures, which often clashed with traditional Gaelic customs.

The Tudor Reconquest and the Flight of the Earls

The 16th century saw the English Crown intensify its efforts to control Ireland. West Cork became embroiled in the resistance movements of local Gaelic lords. One of the most notable figures of this period was Donal Cam O’Sullivan Beare, chieftain of the O’Sullivan clan. After the defeat of Irish forces at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601—a key turning point in Irish history—O’Sullivan Beare led his people on a harrowing 500-kilometer march to Leitrim, seeking sanctuary. Only a handful survived. This event symbolized the collapse of the old Gaelic order and the increasing dominance of English rule.

Following the Nine Years’ War and the “Flight of the Earls” in 1607, many Gaelic lords fled Ireland, paving the way for the Plantation of Ulster and further colonization. In West Cork, land was confiscated from Irish families and given to English settlers loyal to the Crown. This deepened divisions and planted the seeds for centuries of unrest.

18th and 19th Century: Rebellion and Famine

By the 18th century, West Cork had developed a mixed population of Protestant landowners and Catholic tenant farmers. Tensions over land and religious discrimination simmered, culminating in episodes of violence such as the Whiteboy movements—agrarian protests against unfair rents and evictions.

The 1798 Rebellion, inspired by revolutionary ideals from America and France, saw some activity in West Cork, though it was largely suppressed by British forces. Still, the spirit of resistance remained alive.

The most devastating period in West Cork’s history came with the Great Famine (1845–1852). The failure of the potato crop, coupled with British government inaction, led to mass starvation, disease, and emigration. Skibbereen, one of the region’s principal towns, became infamous for the horror it witnessed during the Famine—its name now synonymous with suffering. Over 8,000 people died in the town alone, and many more fled aboard “coffin ships” bound for America, Canada, and Australia.

Twentieth Century: War, Revolution, and Renewal

West Cork played a significant role in the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921). The region was a hotbed of IRA activity, led by figures like Tom Barry and Michael Collins, the latter born in Clonakilty. Notable events included the Kilmichael Ambush, where IRA volunteers killed 17 members of the British Auxiliary Division. These actions helped push the British government toward negotiating the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

The subsequent Civil War (1922–1923) divided communities, including those in West Cork. Collins himself was assassinated at Béal na Bláth in 1922 by anti-Treaty forces, marking one of the most traumatic events in modern Irish history.

Modern West Cork: Culture, Community, and Creativity

In the post-independence era, West Cork remained primarily agricultural, though economic struggles persisted well into the 20th century. By the 1970s and 80s, however, the area began to attract artists, writers, and European settlers drawn to its wild beauty and affordability. This influx helped revitalize the region’s cultural life.

Today, West Cork is known for its lively arts scene, local food movement, and commitment to community sustainability. Towns like Bantry, Skibbereen, and Ballydehob host festivals, markets, and environmental initiatives, while smaller villages retain a sense of timeless rural life.

Though its history has often been marked by hardship, conflict, and change, West Cork has preserved a deep sense of identity. Its landscape holds the memory of centuries—of castles and cairns, abbeys and ambushes—and its people continue to reflect the tenacity, independence, and creativity that have long defined this corner of Ireland.