I have written once before about Sonia Caldwell of Kilcoe Studios. That was eight years ago. In a post titled Kilcoe Studios – Dedication and Passion, I showed you her production of beautiful botanical art calendars and notecards, and gave you a glimpse of her passion for sculpture.

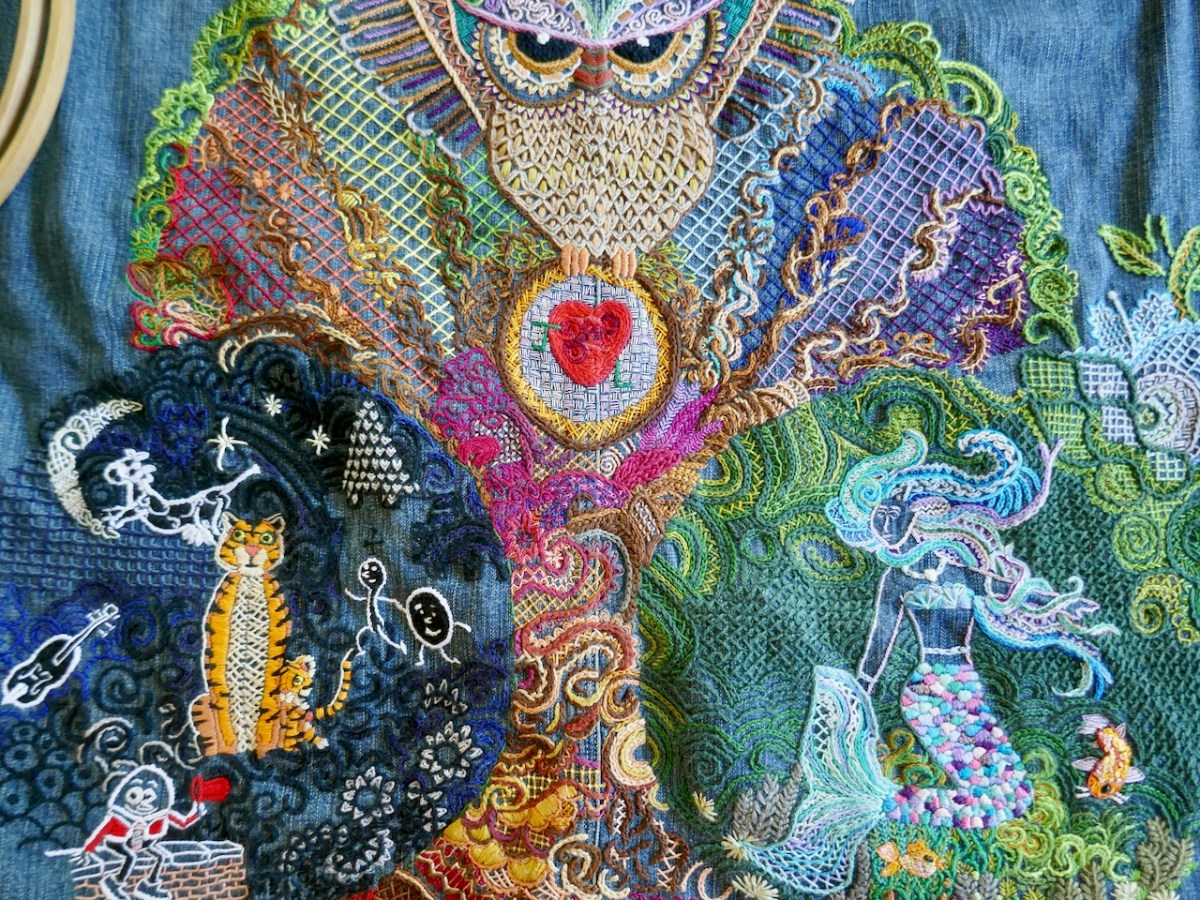

Since then, Sonia has emerged in West Cork as a true champion for heritage and nature, on top of continuing to develop her business and her personal sculpting practice. After a residency at Uillinn, she held a solo show there last month, mainly featuring her sculpture.

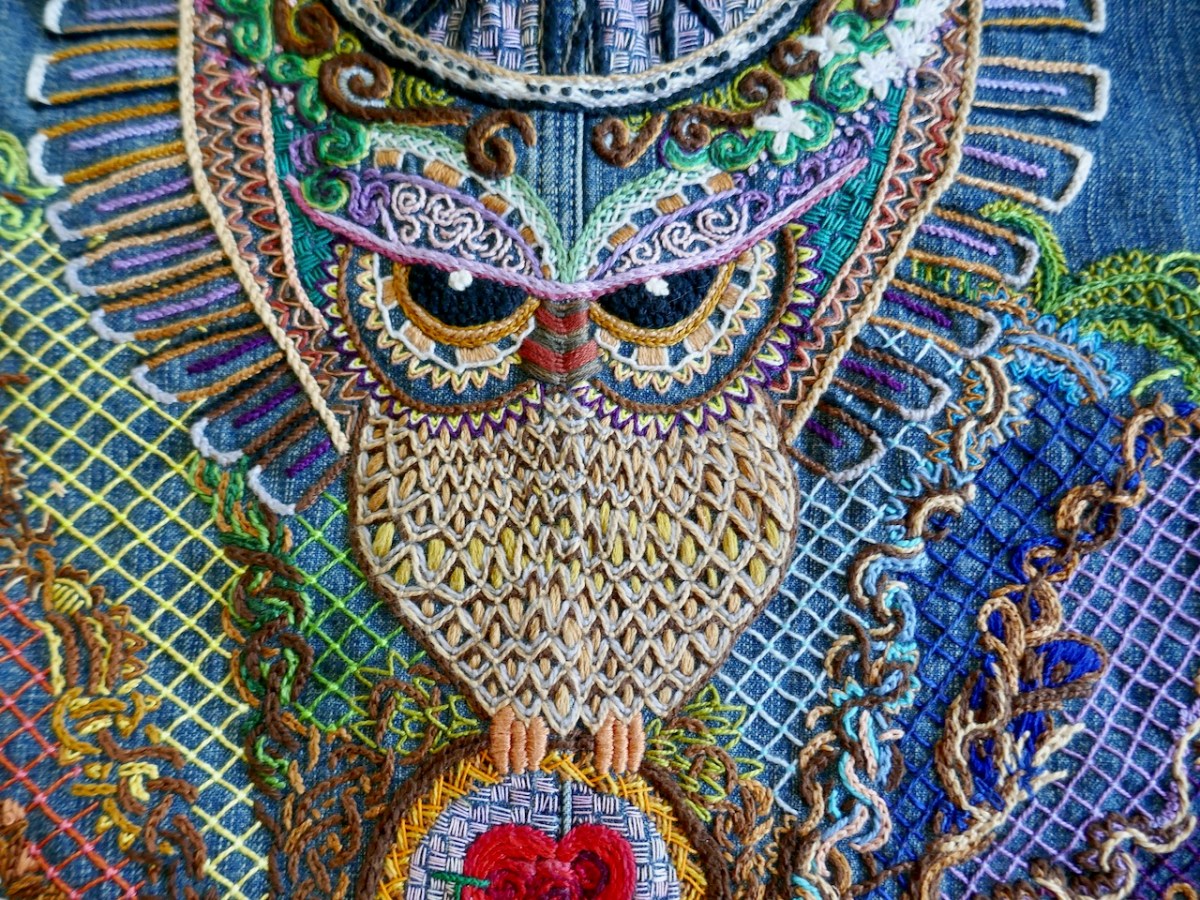

Sonia works in limestone, clay and natural materials such as mosses and twigs. Her work has an ethereal quality, explained by her personal spirituality. Her figures, small and large, are seeking to find their path, or answers to their questions.

They ponder an empty church, march along a pilgrim route carrying their burdens, or gaze into the distance mulling over some otherworldly mystery.

The launch of the exhibition was haunting. Sonia and singers, directed by Susan Nares, entered singing: chanting, rather, in a slightly Gregorian way, in English and Irish.

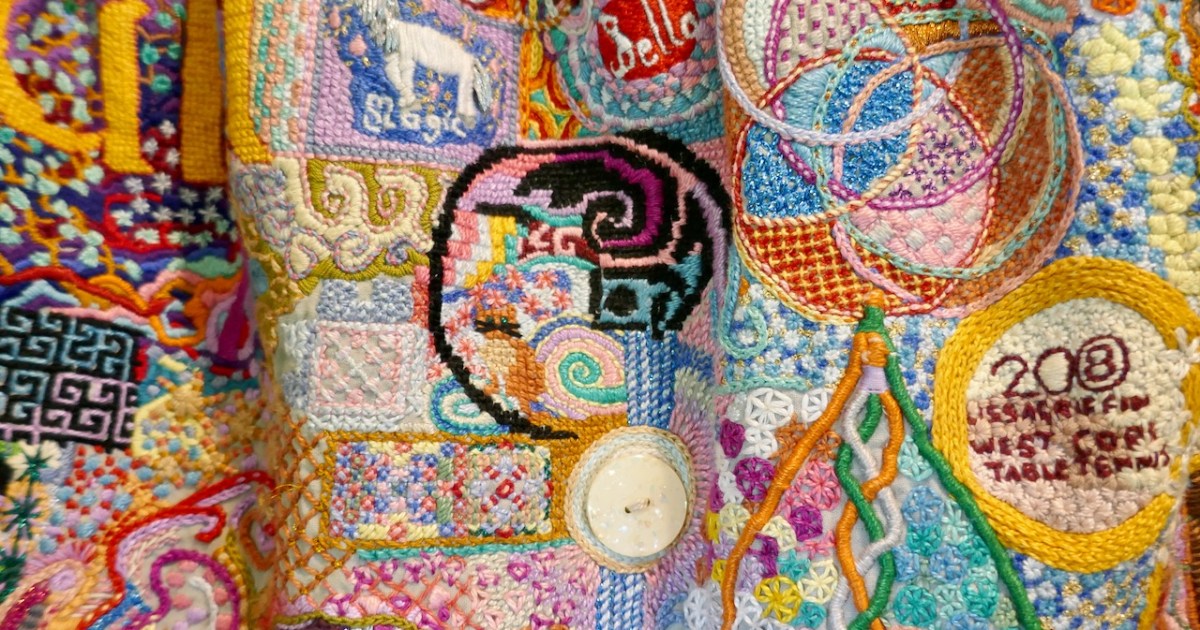

That’s the fine art side of Sonia. But her other passion is for the natural world and for all those heritage crafts that will die, if people like her don’t learn, nurture and revive them. She has opened a shop in Ballydehob, where she sells her own artwork, and items by others made from all natural materials.

The shop is where she also hosts her workshops – often facilitated by herself and occasionally by others. All the workshops are designed to get us engaging with heritage crafts and materials sourced from the fields, hedges and water around us. And they are great fun!

Just in the past year in that shop I have learned to make a basket from brambles (yes, don’t worry, de-thorned) – that’s my friend Julia splitting a long bramble above. I have made an autumn sculpture (“don’t call it a wreath!”) and a Christmas wreath, both facilitated by the wonderful Liz O’Leary and from foraged materials.

And I have gone on two foraging walks. The latest walk was last weekend, and it featured my first ever cup of nettle tea (delish!) and a picnic on the banks of a river with crackers and cake made from various gleanings and flavourings – toasted Wood Avens seeds anyone?

Sonia has also single-handedly revived Wren Day (also known as St Stephen’s Day in Ireland and Boxing Day abroad) in Ballydehob and taught us how to make the traditional rush hats worn by the Wren Boys. See Robert’s post The Wran for more on this unique Irish tradition – he was an enthusiastic participant.

All towns and villages deserve a person like Sonia – the person who won’t let the traditions die and who encourages the rest of us to look around us and really see what the land has to offer. We are lucky she chose West Cork as the place to nurture her own unique and mighty talent and to draw the occasional spark of creativity from the rest of us.