I am a firm believer in wart wells: there is one at Clonmacnoise, the holy centre of Ireland, and some years ago when I was visiting the place I dipped my finger – warts and all – in it. Within… well, perhaps it was two or three weeks… the warts had gone. The Cynics among you will be saying that they might have gone anyway, but I have had other warty experiences to reinforce my beliefs. When my daughter Phoebe was 11 years old and we were living back in Devon she had a really bad outbreak of warts on her hand. The doctor couldn’t recommend anything but our neighbour was very sure of what to do: take her to see Auntie Grace who lived up the lane. We duly knocked on Auntie Grace’s door and showed her Phoebe’s hand. “That’s alright, Dear” she said, and shut the door. That was all. But within a week (more or less) the warts had vanished completely, never to return.

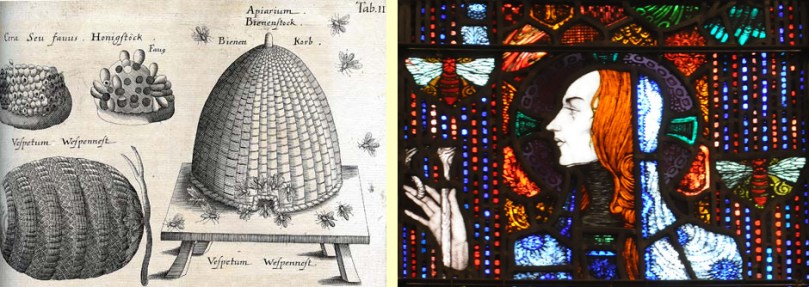

Bullaun Stones abound in Ireland. They are usually found at sites with ecclesiastical connections – as the two examples above (and this one), but this association does not reduce or affect their traditional uses: to cure or to curse. The Irish word Bullán means ‘bowl’ – a water container. At pilgrimage sites, such as St Gobnait‘s Well, Ballyvourney, the bullaun stones often hold smooth rounded pebbles – perhaps incised with a cross – which are turned around each time a pattern or procession is completed.

Bullaun at St Gobnait’s Grave, Ballyvourney

In the sixth century, the Council of Tours ordered its ministers “…to expel from the Church all those whom they may see performing before certain stones things which have no relation with the ceremonies of the Church…” Such an order doesn’t seem to have prevented folk traditions of curing continuing into the twenty-first century.

Traditionally, in Ireland similar stones are used for less benign purposes than curing warts or other maladies. Thankfully not in West Cork but in faraway Cavan a group of bullaun basins and stones at the ruined Killinagh Church are associated with curses, as explained here by Harold Johnston in a 1998 interview: “…if you wanted to put a curse on someone, you turned the stones anti-clockwise in the morning.” However, the curse had to be ‘just’ otherwise it came back to curse you in the evening!

Nearer to home, in County Cork, are the ‘cursing stones’ known locally as the Clocha Mealachta – not in this case associated with bullaun basins but kept hidden under a slab of rock, which seems a bit sinister to me.

I prefer the legends which show bullaun stones as a force for good: in more than one location they are said to be associated with a local saint. St Kevin of Glendalough (in County Wicklow) drank every morning from the Deer Stone, a bullaun which miraculously was always filled with milk.