How did a church in an Irish country town become a repository for some of the greatest treasures of the Arts and Crafts movement of the early 20th century? That church is St Brendan’s Cathedral in Loughrea, Co Galway, which we visited last week.

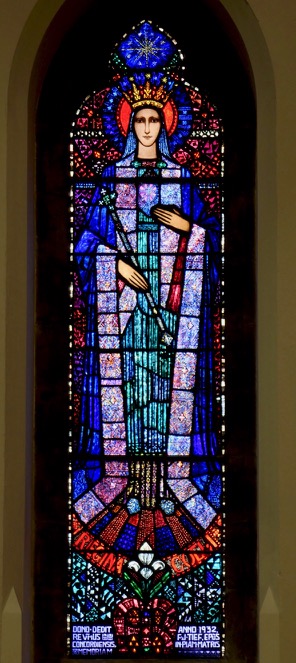

Evie Hone’s St Brigid window

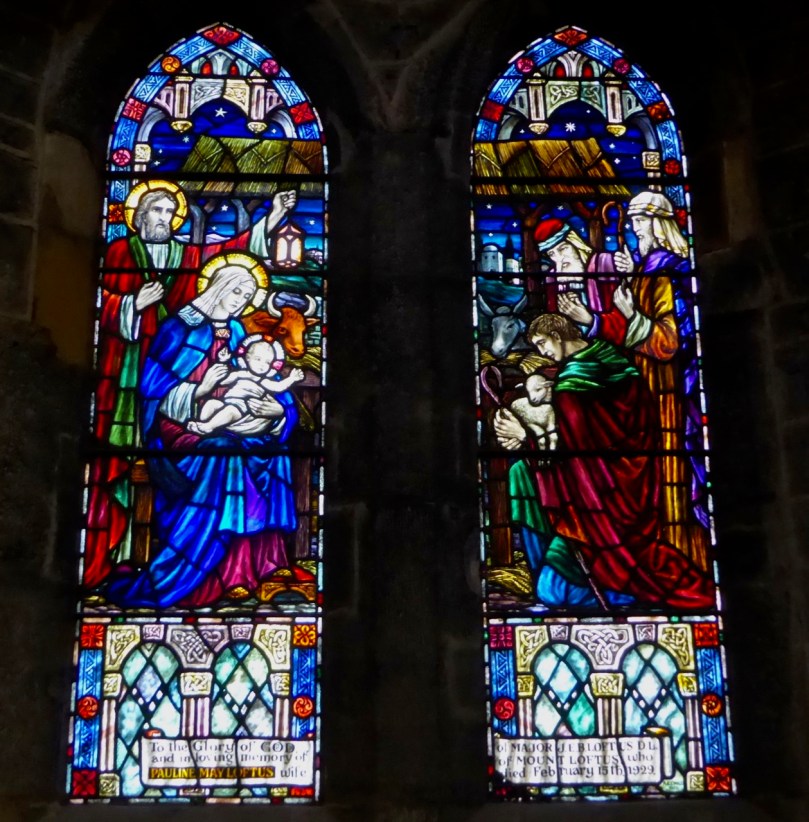

The Arts and Crafts movement was a reaction against soulless methods of industrial production which emphasised repetitive tasks and removed the link between the worker and the final product. Such factory processes were eventually applied to works of art, such as stained glass windows, where numerous workers would be employed to assemble a final product. Within the movement, artisans, artists and makers sought to get back to a former time, often conceived as medieval and highly romanticised, when craftsmen and women designed and executed exquisite works from start to finish.

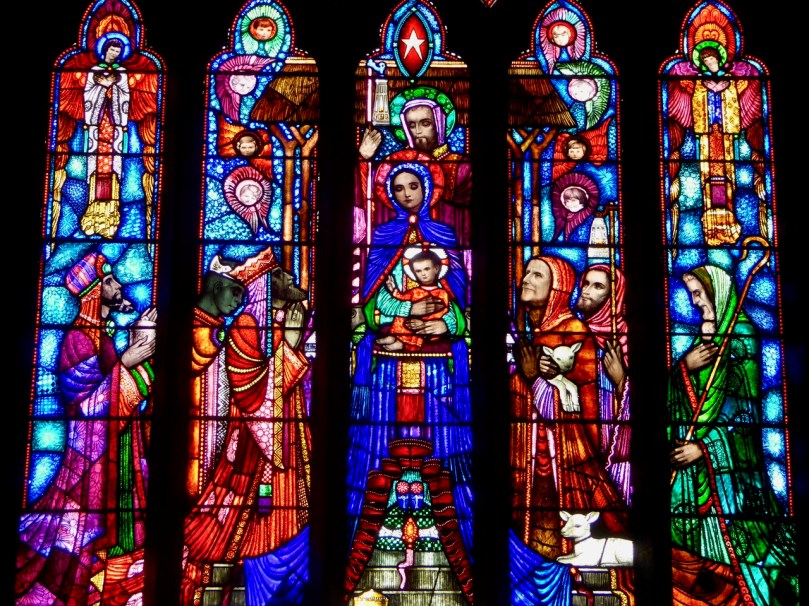

Queen of Heaven window by Michael Healy

So where does Loughrea come in? Well, for a start, it was the home of Edward Martyn, a wealthy enthusiast for all things Gaelic Revival including language, theatre, literature, music and art. Heavily influenced by the philosophies of the Arts and Crafts movement, particularly by those of William Morris, he worked with Sarah Purser to found An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass) as an artist/maker stained glass studio. Not a small part of their initial success was his ability to promise commissions from the decoration of St Brendan’s Cathedral.

The Stations of the Cross are by Túr Gloine artist Ethel Rhind and are executed in the unusual opus sectile mosaic technique

Thus it is that this church, in outward appearance very much like the prevailing neo-Gothic style of the end of the nineteenth century, is packed with the work of the most eminent women and men artists of the opening decades of the 20th century. Yes, that’s right, women and men – the Arts and Crafts movement empowered women artists like few such movement had before (or since, perhaps).

The Agony in the Garden by A E Child, detail

It takes a moment to realise what you have entered – initially the church interior seems familiar and unremarkable, almost heavy in its preponderance of marble, tile and dark wood.

But as the eyes adjust, you can be permitted a gasp or two as you realise that all the capitals are carved with scenes from the life of St Brendan, that there are fine sculptures here and there, that the arm of each pew has been individually decorated with idiosyncratic characters, that are are art-nouveau-looking light standards throughout the aisles, that the stations of the cross are unlike any you’ve seen before, and finally that the stained glass windows are numerous and beautiful.

Two scenes from the Death of Brendan, carvings by Michael Shortall

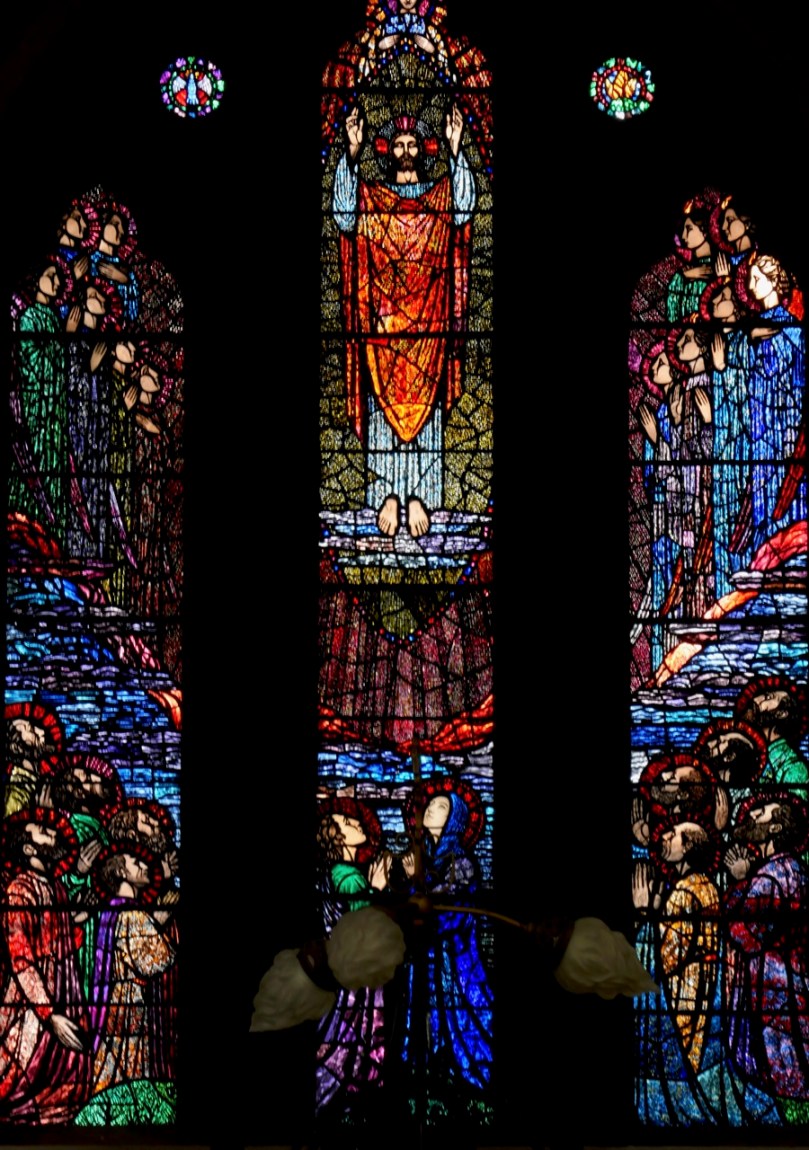

All the Túr Gloine stained glass arts are represented here: A E Child, Michael Healy, Ethel Rhind, Catherine O’Brien, Beatrice Elvery, Evie Hone and Hubert McGoldrick. There is even a small St Brendan window by Sarah Purser herself – a rarity as she mostly confined herself to the management of projects rather than glass-painting.

One of the very few stained glass windows actually executed by Sarah Purser herself – a Brendan image in the porch of the church

The stone carving is mostly the work of Michael Shortall, a student of John Hughes, the foremost sculptor of his day who provided bronze figures for the church. Eminent architect William Scott was engaged to design church furnishings and was responsible for the side altars, the entrance gates, the altar vessels and candlesticks, the baptismal font and altar rail.

Each pew arm has a whimsical creature – this one was no doubt intended to concentrate the mind on mortality

The woodwork was all done locally, with the workers encouraged to use their skills to depicts beasts and mythical figures, in much the same way that medieval craftsmen had done.

The museum contains an outstanding collection of sodality banners designed by Jack B Yeats and his wife, Cottie, and embroidered by the Dun Emer Guild. Above is the original design and the finished product

But that’s not all. Beside the church is a small museum, similarly packed with treasures. In particular, here is where you will see the work of the Dún Emer Guild, a women’s cooperative enterprise that designed and supplied materials (altar cloths, vestments, rugs, tapestries) to churches and others. Strongly influenced by traditional Irish designs such as scrollwork, interlacing, high crosses and Book of Kells symbols, the works supplied to St Brendan’s are wonderful examples of Irish Revival motifs, skillfully embroidered in gorgeous colours.

The Museum holds other artefacts too, including extremely rare medieval wooden carvings: most wooden statues were destroyed by the Puritans and very few have survived. There are also fifteenth century vestments, original drawings and sketches by Irish artists, altar vessels, and stained glass cartoons.

Twelfth or Thirteenth century wooden statue of the Virgin or Child

This post is a small introduction to the wonders of Loughrea Cathedral. About 40 minutes east of Galway and just south of the M6, this church is a must-see for anyone interested in the history of Ireland and its Arts and Crafts movement. The only comparable experience is the Honan Chapel in Cork.

Michael Healy’s magnificent Resurrection window

All I can do here is show you a representative sample of what we saw and encourage you to go see the totality for yourself. You won’t regret it.