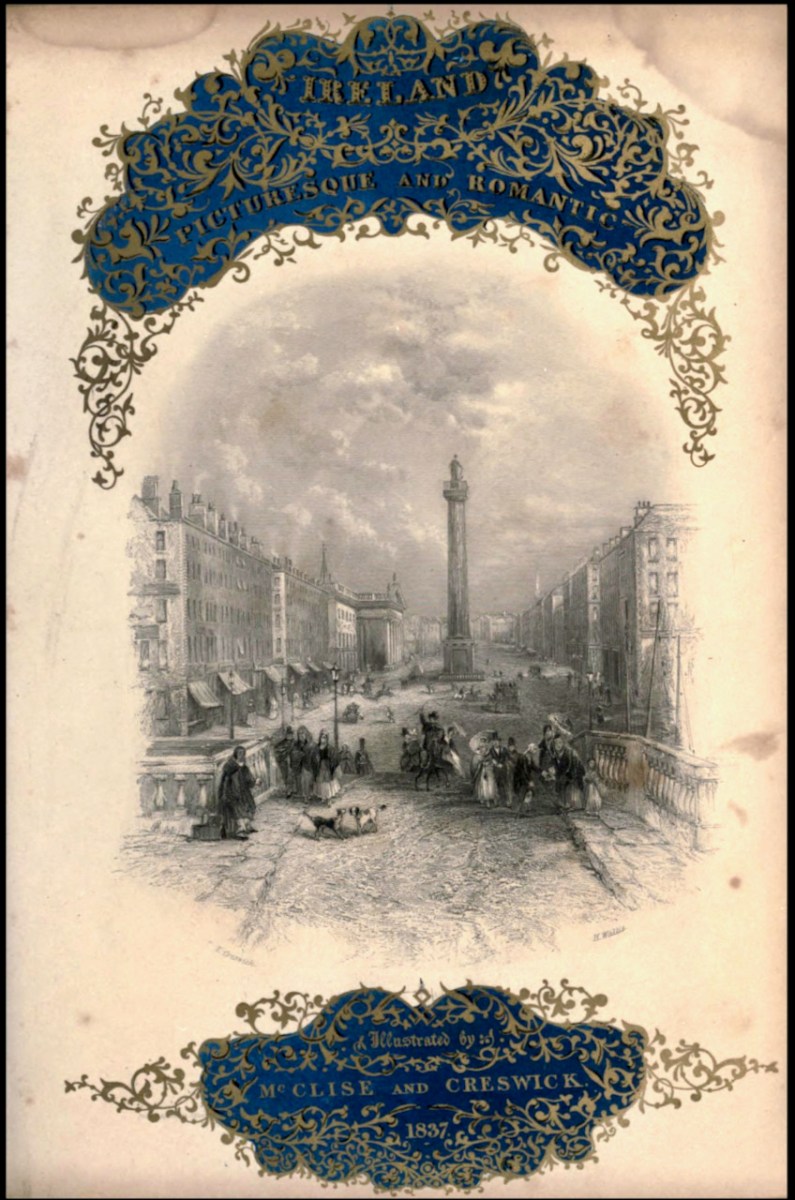

I’m fascinated by how artists captured Ireland through the centuries and have recently discovered a new one – Thomas Creswick. We mostly know Creswick’s Irish work through the engraving of his Irish landscapes for nineteenth century books on Ireland.

First – who was Thomas Creswick? He was born in Sheffield in 1811, but is always associated with the Birmingham School of painters. Victorian loved their romantic landscapes and Creswick was a favourite, thanks in large part to the innovation of engraving, through which paintings could be reproduced in black and white and mass-produced. His self portrait shows a darkly handsome young man, fashionably dressed and coiffed.

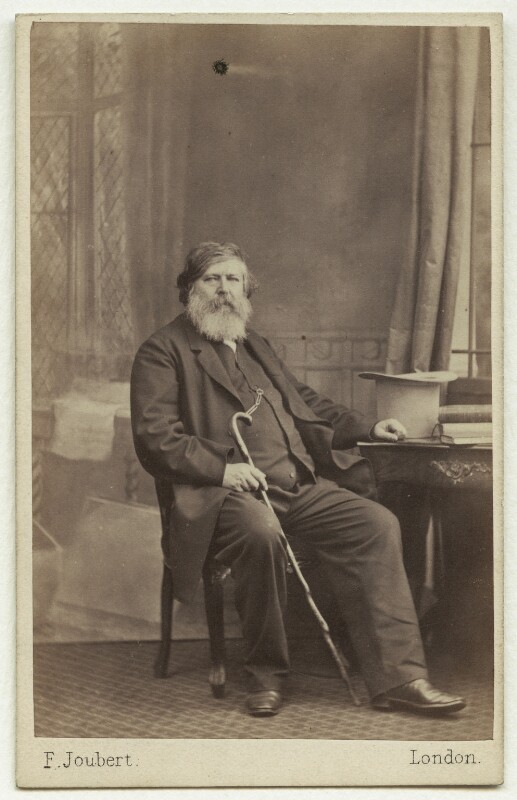

Here he is as an older man, in a photograph from the British National Portrait Gallery (used under license). He was painted at around this time by his friend William Powell Frith and the painting shows the same distinguished gentleman. However, the painting, on the Royal Academy website, is accompanied by a pen-portrait which is less complimentary than the painting.

William Powell Frith counted Creswick as one of his best friends, describing him as ‘good nature personified’. This tasteful portrait, composed in muted tones, certainly depicts a man of benevolent appearance and dignified bearing. However, this portrayal is at odds with many accounts of Creswick’s appearance and personality. Frith’s daughter recalled a ‘festive, rollicking and amusing’ man whose conversation was peppered with swearwords and who ‘was too fond of both food and drink to be always in the best of health’. Creswick’s larger-than-life character was not universally appreciated. Other landscape artists, in particular, accused him of exerting his influence amongst the Academicians to exclude his rivals from the institution. Creswick’s detractors made much of his unkempt appearance and reputed aversion to soap and water, nicknaming him ‘the big unwashed’.

Whatever about his personality, his skill as a painter was never in question, and drew high (and rare) praise from Ruskin for his attention to detail and his ability of draw directly ‘from nature’. The only other landscape artist Ruskin praised was Turner. Creswick did indeed draw from nature, doing many of his sketches and some finished paintings en plein air, a rare enough approach in those days.

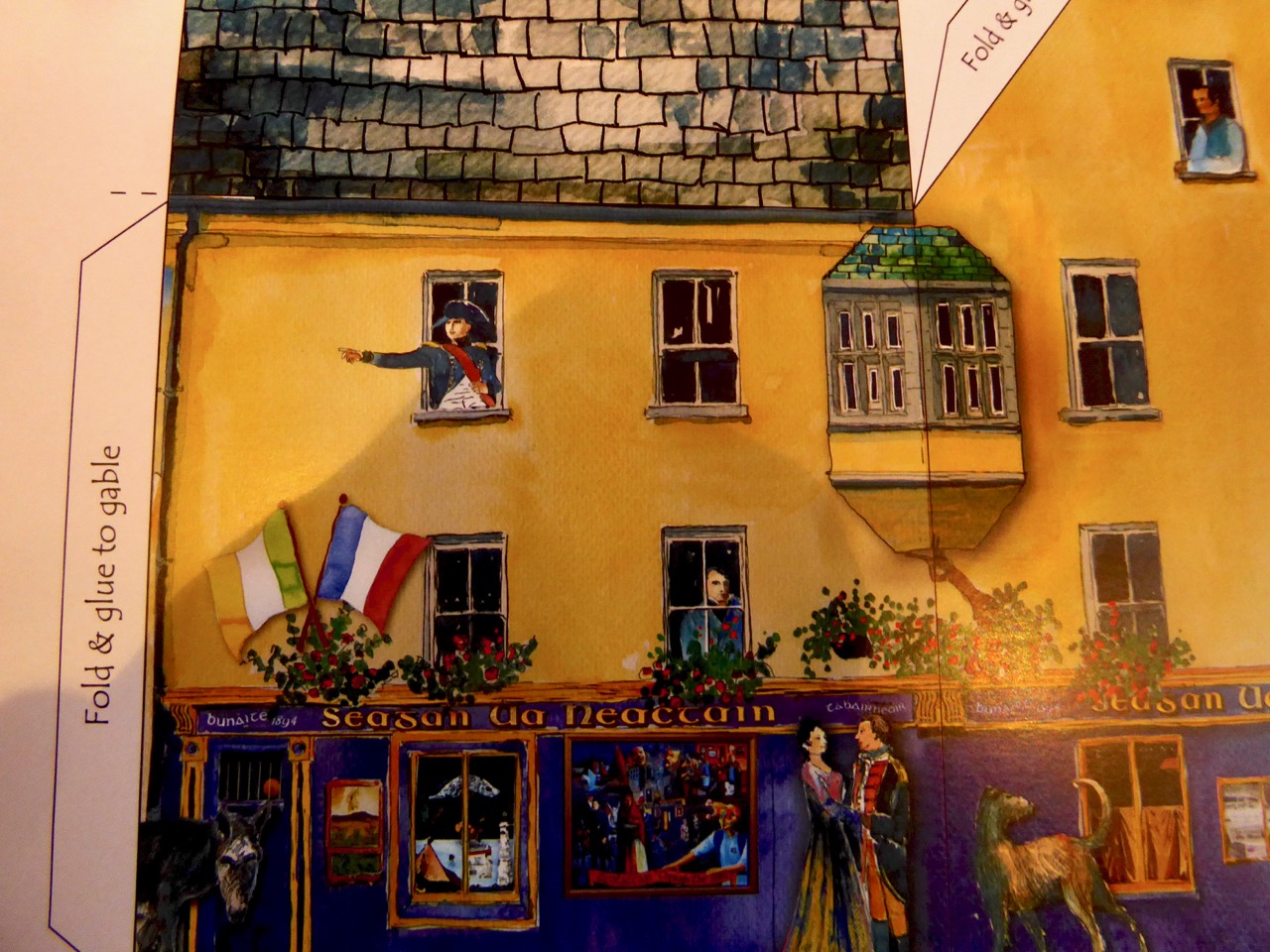

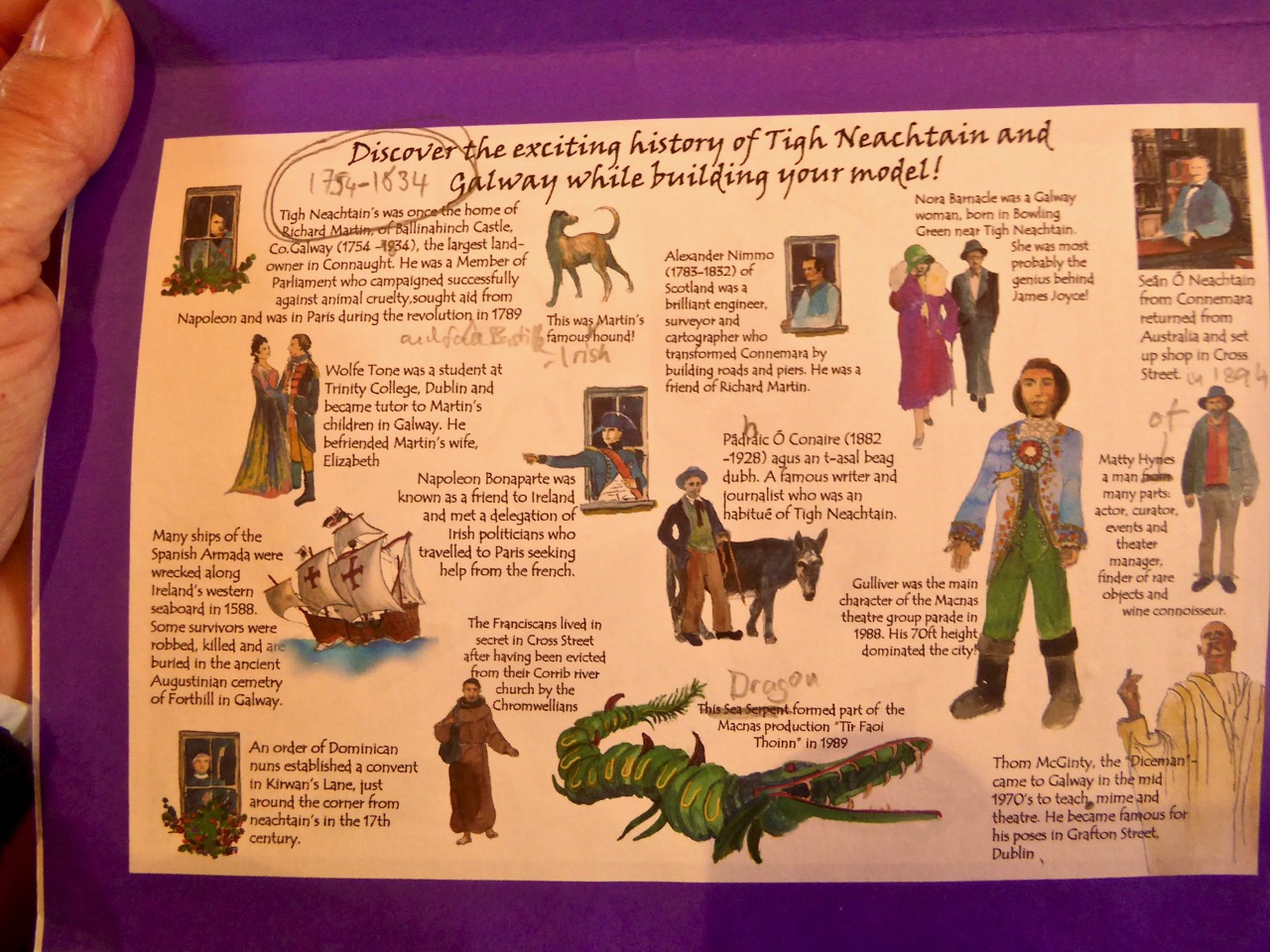

Although most of his paintings were of rocky glens and pastoral river scenes in England and Wales, he travelled to Ireland and visited many of the famous beauty spots then becoming favourites with British tourists. His illustrations (engravings of original paintings) can be found mainly in two volumes. The first is Picturesque Scenery in Ireland (no publication date) with all the illustrations by Creswick, and the accompanying text by “A Tourist”. The other is Ireland, Picturesque and Romantic, published in 1837/38 with text by Leith Richie. Both are available on the marvellous Archive.org. Some of the illustration are the same in both books and some are different.

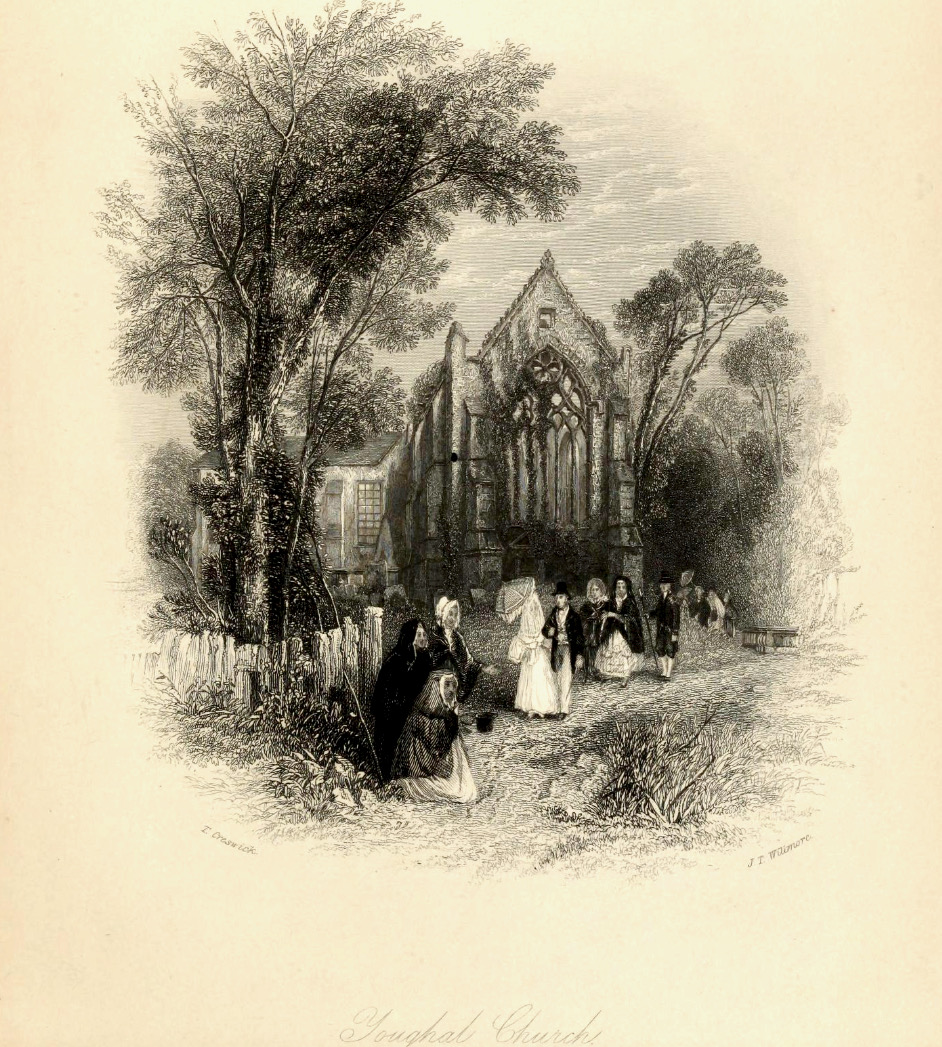

I’ve chosen to confine the illustrations I’m using for this post to Cork. Let’s start at the far east of the county and move west. So – first up is Youghal. Having been in Youghal recently for the excellent Youghal Celebrates History, which concentrated on St Mary’s Collegial Church and its 800 years of history, I loved Creswick’s depiction. He captures the roofless (now roofed) ruin, rendering the complex tracery of the tall window very accurately. His polite and well dressed ladies and gentlemen, visiting the romantic ruins, must run a gauntlet of begging women, one of who is wearing the Cork hooded cloak.

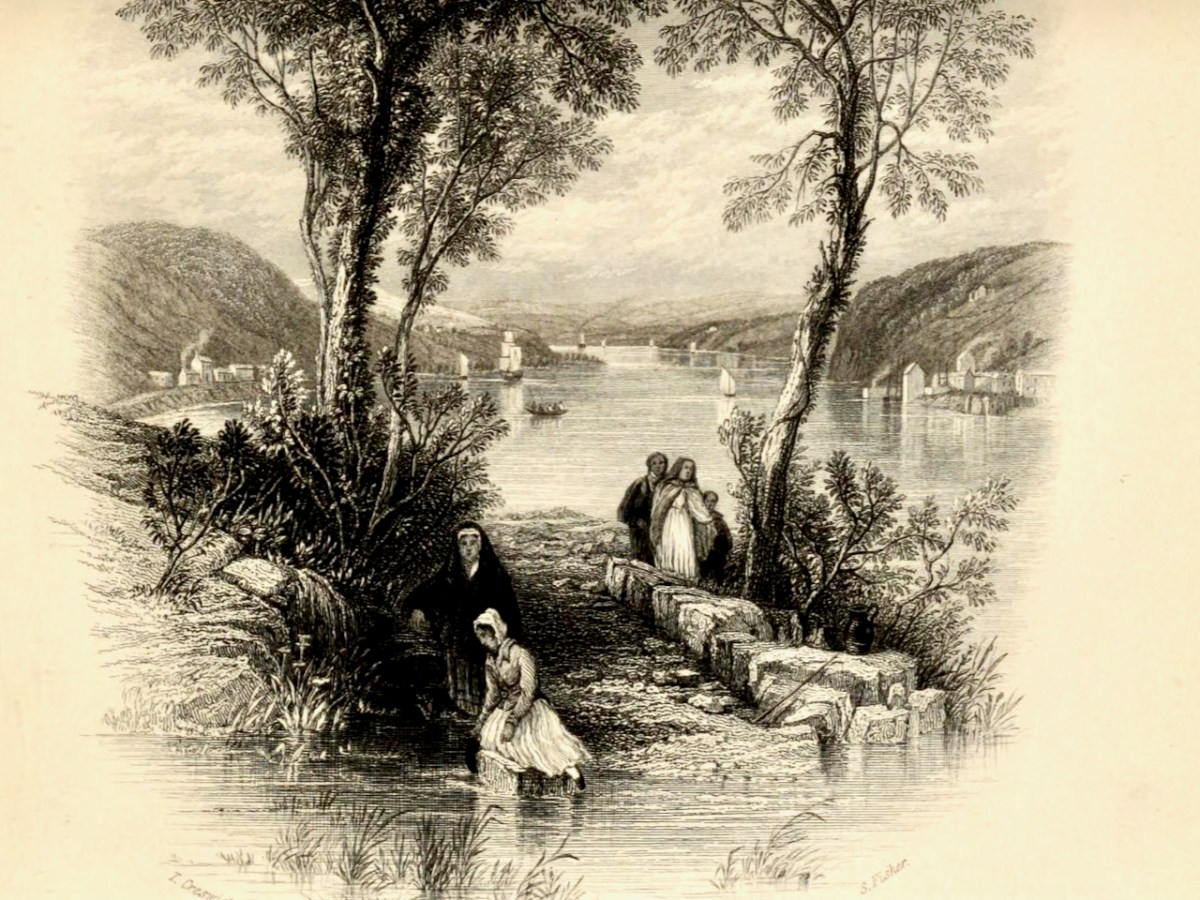

Moving westwards, we come to the ferry at Passage West – a journey Robert and I took only yesterday. For us it was a quick trip on the ultra-efficient car ferry, but Creswick shows an altogether more leisurely affair involving a rowing boat. The view of the boat is framed between trees. Figures in the foreground include a woman drawing water from the River Lee in a ewer – not something I’d want to do today.

The Passage Ferry Scene is a good example of the Picturesque Idiom, which had its conventions. According to Simon Cooke on The Victorian Web, artists such as Gainsborough and Constable

followed the compositional rules of the Picturesque and Creswick similarly adheres to its iconography. Drawing on the many examples of the type, he deploys a semiotic made up of trees (typically placed as framing devices), a well-defined foreground (usually populated with peasants or cattle), a stream, river or pathway, an architectural feature (castle, house, church), a large expanse of sky, and a prospect (often of mountains), or a vista reaching into the far distance.

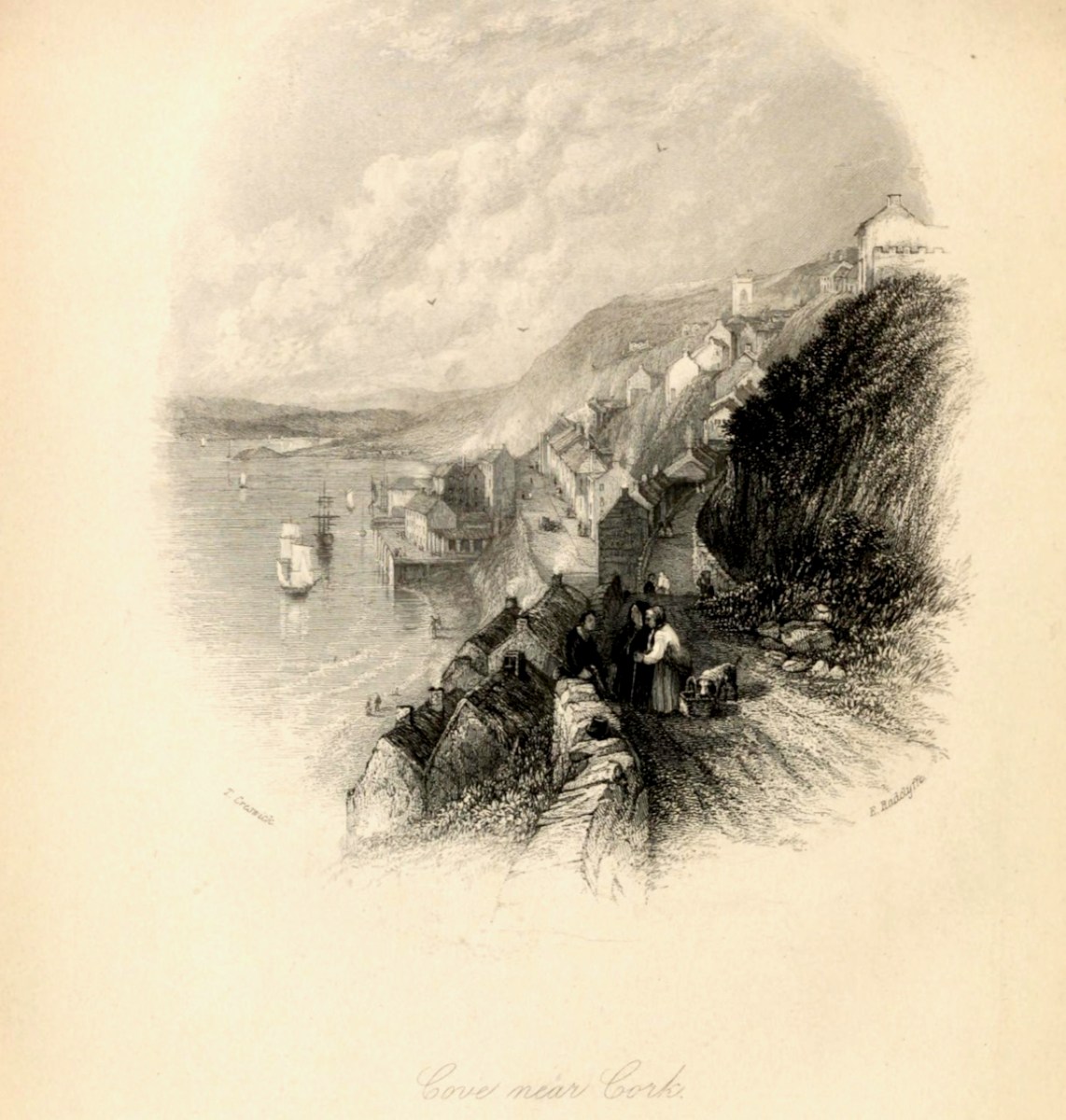

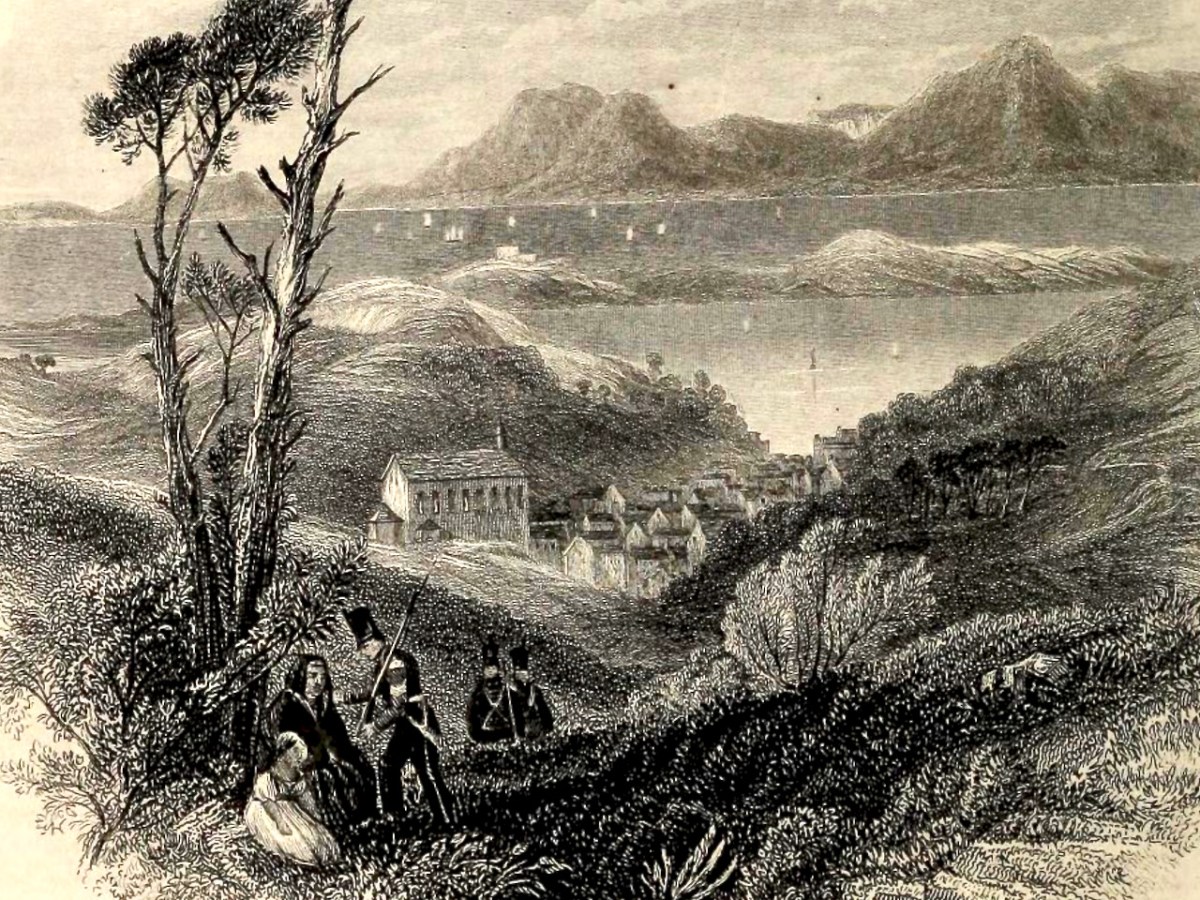

Next stop is Cobh (below, then called Cove, afterwards rechristened Queenstown, and finally reverting to Cobh). Creswick’s image is of an older town, before extensive docks were built, and captures the steepness of the roads and the precipitous way the houses cling to the hills.

Those steep narrow streets are still there, in Cobh. Below the seated figures is the area of fishermen’s cottages known as The Holy Ground. There’s no sign yet of the magnificent St Colman’s Cathedral, which didn’t get started until the 1860s. See the lead image in this post for a closer view of Cobh.

Blackrock Castle has to be one of the most painted pieces of scenery in Cork – so romantic, as it sits on its watery outcrop on a bend of the River Lee. In the foreground a family rows out to do what – set a lobster pot? – while a gaff-rigged sloop makes its way upriver.

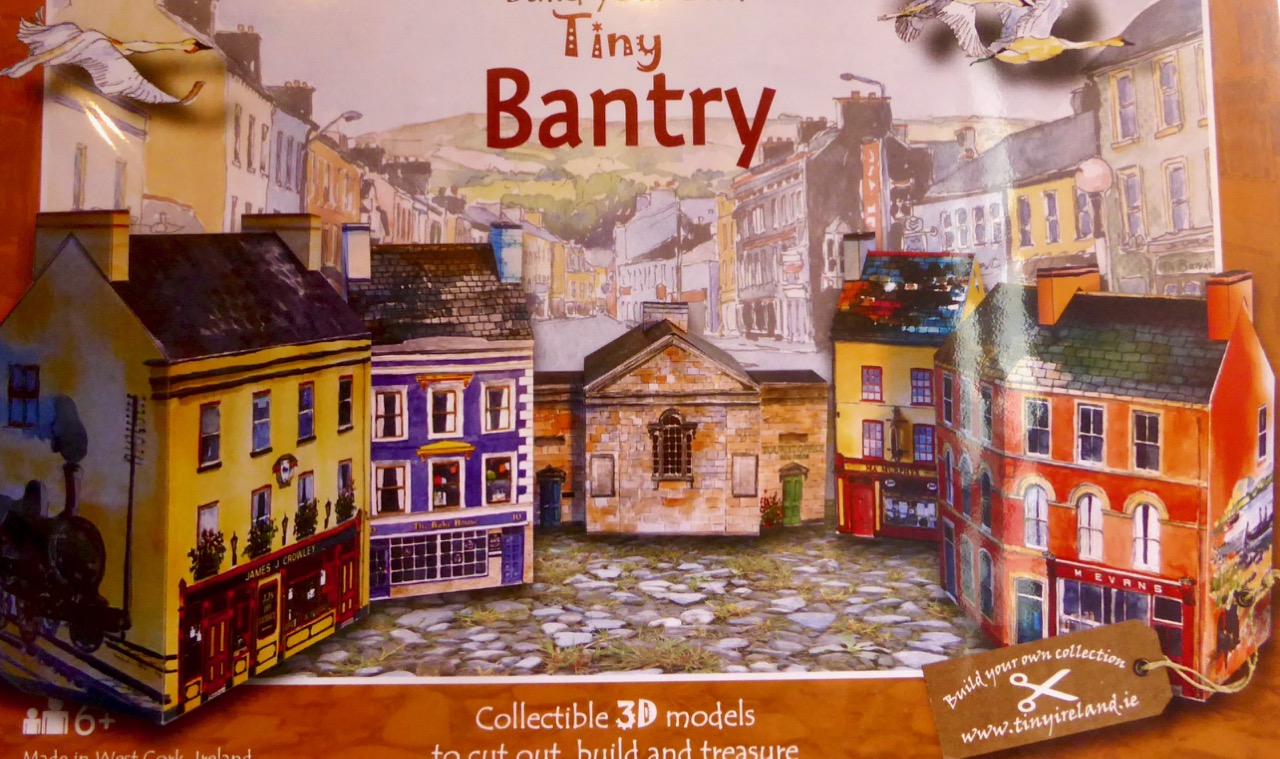

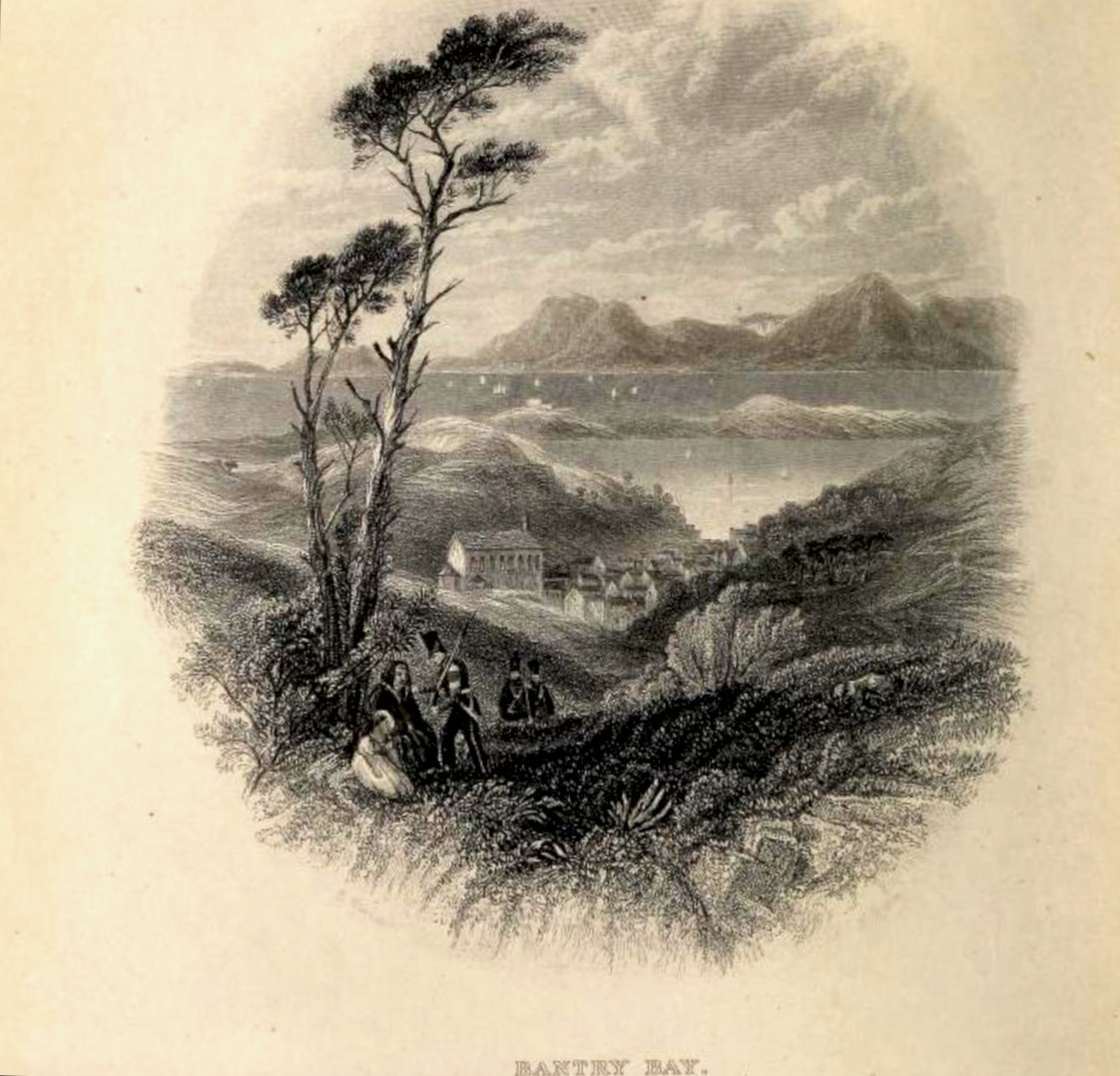

Our final scene is Bantry Bay. St Finbarr’s Church was built already in the 1820s, even before Catholic Emancipation, and sits proudly on an eminence above the town. In the foreground is an enigmatic scene in which a soldier (with other soldiers advancing up the hill) is grasping the shoulders of a woman, who sits with a young girl under a tree. Are we witnessing an arrest, or a compassionate gesture of assistance?

Bantry Bay is spread out beyond the town, which slopes down to the water. The Battery on Whiddy Island, long in ruins, is clearly visible. The mountains of the Beara rise in the background, including the Sugarloaf on the right.

There is a full-colour painting by Creswick of Glengarriff but it is not copyright-free. You can view it here. If you want to see more of his illustrations, take a look at the books on archive.org – Dublin and Wicklow are well-represented.