We have a particular reason for re-publishing this 2016 post, one of our personal favourites, this week. The church urgently needs conservation and this West Cork gem is in danger. The group trying to save it is looking for help. If you feel like donating, here’s the link: https://www.gofundme.com/f/west-cork-hidden-gem

But no matter if you donate or not, you will love this little church and its amazing features and we encourage you to visit it when you can.

What follows is a substantially re-written version of a post originally published in Feb 2016.

———–

This week when we were passing though Timoleague I had a fancy to see inside the Church of the Ascension as I had heard it was ‘worth a look’. Understatement of the century! What we saw was astonishing, beautiful, and overflowing with history and stories.

The key is kept at the Post Office on the main street – just ask

This Church of Ireland building is typical of the simple gothic revival style favoured by the funders – the Board of First Fruits. (Read more about this almost-forgotten organisation in a post from the always excellent Irish Aesthete.) Built from the ruins of an earlier (probably medieval) church it was consecrated in 1811 but enlarged later in the 19th century. The pointed-arch windows and the square tower with louvre vents are unremarkable features on the exterior, but open the door and step inside and you enter another world.

The mosaics are the most obvious (although by no means the only) glory of this church. Designed to commemorate members of the Travers family (yes, the same Travers whose memorials dot the walls of St Fin Barre’s) they cover the entire interior of the church, apart from the hammer-beam ceiling in the nave. They incorporate motifs in several traditions – Christian, Jewish and Islamic.

Above the west doorway is the Ascension scene – the apostles are rather conventional but I love their colourful robes and the flower borders. Below them is an angel font, similar to a pair in St John’s Catholic Church in Tralee, made of Carrera marble, with yet more mosaic detail.

Members of the Travers family are named in mosaic around the walls – Robert Valentine Travers of the Munster Fusiliers was only 22 when he fell at Gallipoli.

The mosaic tiles were made by Minton, as were the encaustic tiles on the floor (below). Minton is known for its bone china but in fact it was also was the leading producer of British ceramic tiles during the 19th century.

In the chancel, above the marble altar, the ceiling is covered in painted angels, while the walls are mosaic, parts of which have been gold-leafed. The richness of the detail and the vision that dictated such a glorious conjunction of imagery and colour is jaw-dropping, and mark this little provincial church as part of the influential Oxford Movement of the Victorian era that aimed to return ornamentation and beauty to spaces of worship.

This is the great High Church and Low Church debate. A group called the Cambridge Camden Society promoted a return to gothic architecture: the classical style was seen as pagan, while the great gothic cathedrals of Europe represented the apex of Christian architecture. (More about this in Part 2, which will concentrate on the stained glass and the architecture of the church.)

Installing mosaic is a time-consuming and expensive process – this one involved importing artisans from Italy and the parishioners eventually received help from an unexpected quarter. The final series of installations was paid for by an Indian Maharaja!

The Pelican is a Christian symbol of sacrifice – the pelican was believed to provide her own blood to her young when no other food was available

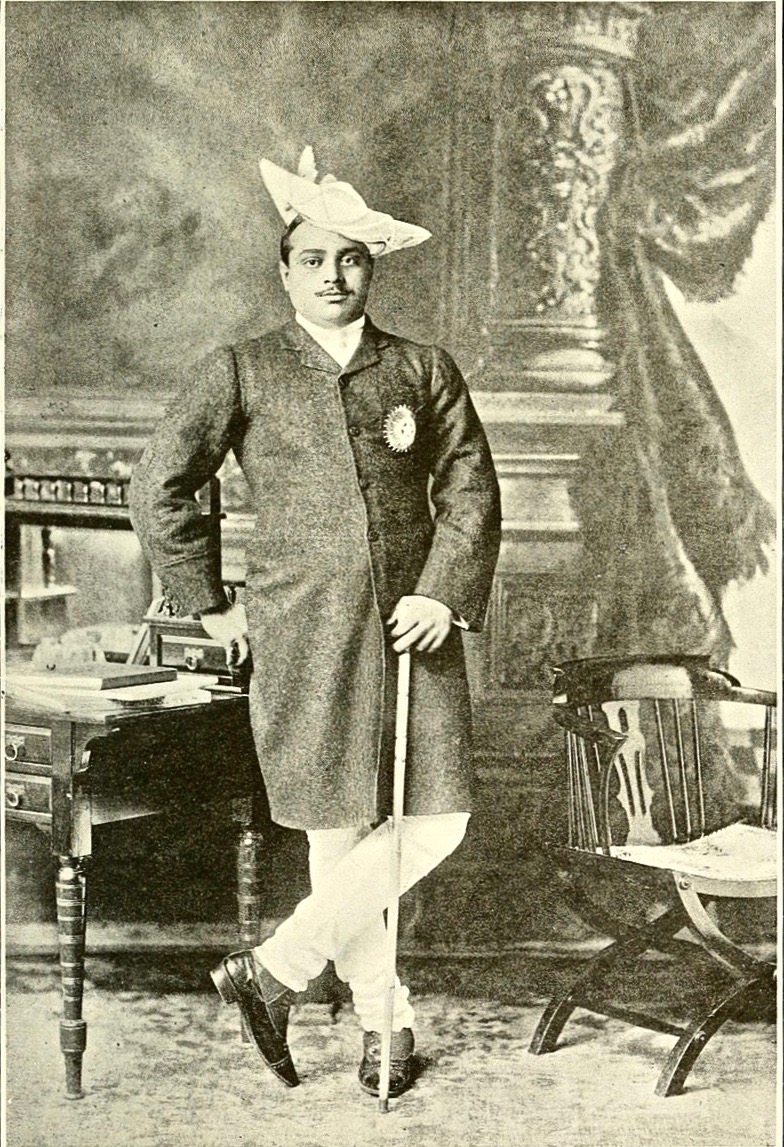

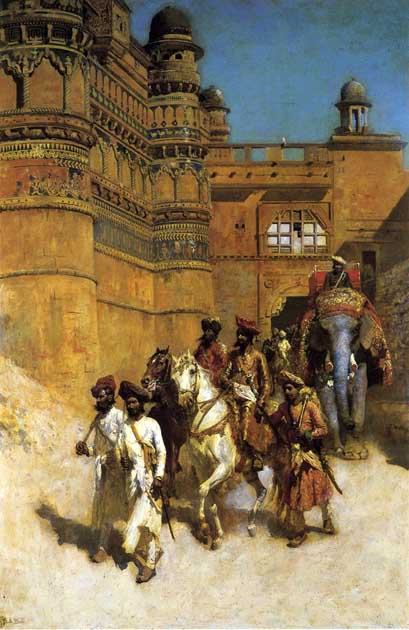

Madhav Rao Scindia was the Maharaja of Gwalior. He was wealthy and looking for places to spend his money. What, you don’t believe that? Just read this story about the fabulous and secret treasure chambers of Gwalior. No, I jest – in fact, he was a highly-educated ruler who did much to modernise his state but he was only 9 years old when he inherited the title from his father, pictured below leaving his palace in state.

The Maharaja of Gwalior Before His Palace, C 1887 by Edward Lord Weeks

The Maharaja of Gwalior Before His Palace, C 1887 by Edward Lord Weeks

The British appointed as his surgeon and tutor an Irish doctor from Timoleague – Dr Martin Crofts. A long friendship grew, based on mutual respect (and shared tiger-hunting expeditions) and it is said that Crofts saved the life of the Maharaja’s son.

The Maharaja in his prime

When Crofts died suddenly in 1915, after only a year of retirement, and was buried in Timoleague the Maharaja funded the completion of the mosaics as a memorial to his friend and mentor.

Thus, a tiny and obscure church in Timoleague invokes not only a great architectural movement but, like the memorials last week, echoes of the Empire and an unlikely international friendship. But this is not the last of the story – in the next post we will explore the other glory of this little church, the stained glass windows. In their own way they also link Timoleague to the great artistic trends of their age.