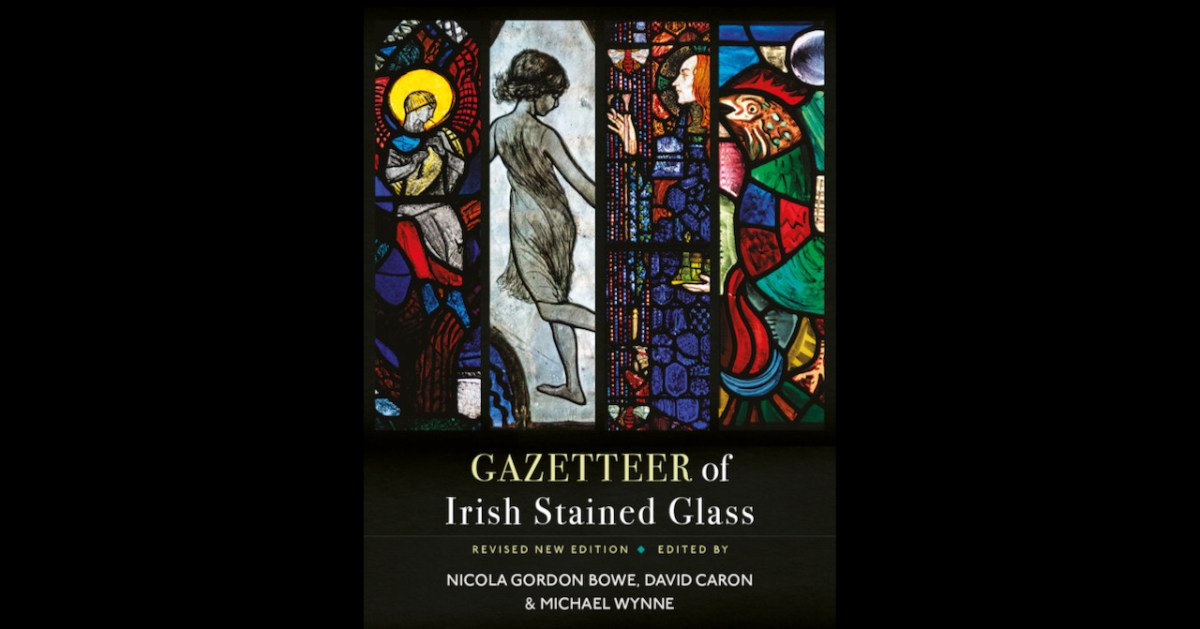

Friends, take note – this is an ideal Christmas present! If it has never occurred to you to take a drive, a walk or a cycle through any part of Dublin, dropping into churches along the way, this book will convince you that it’s the ideal way to spend a day, surrounded by history and beauty.

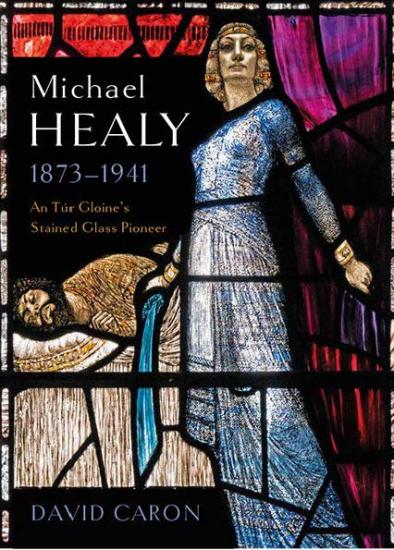

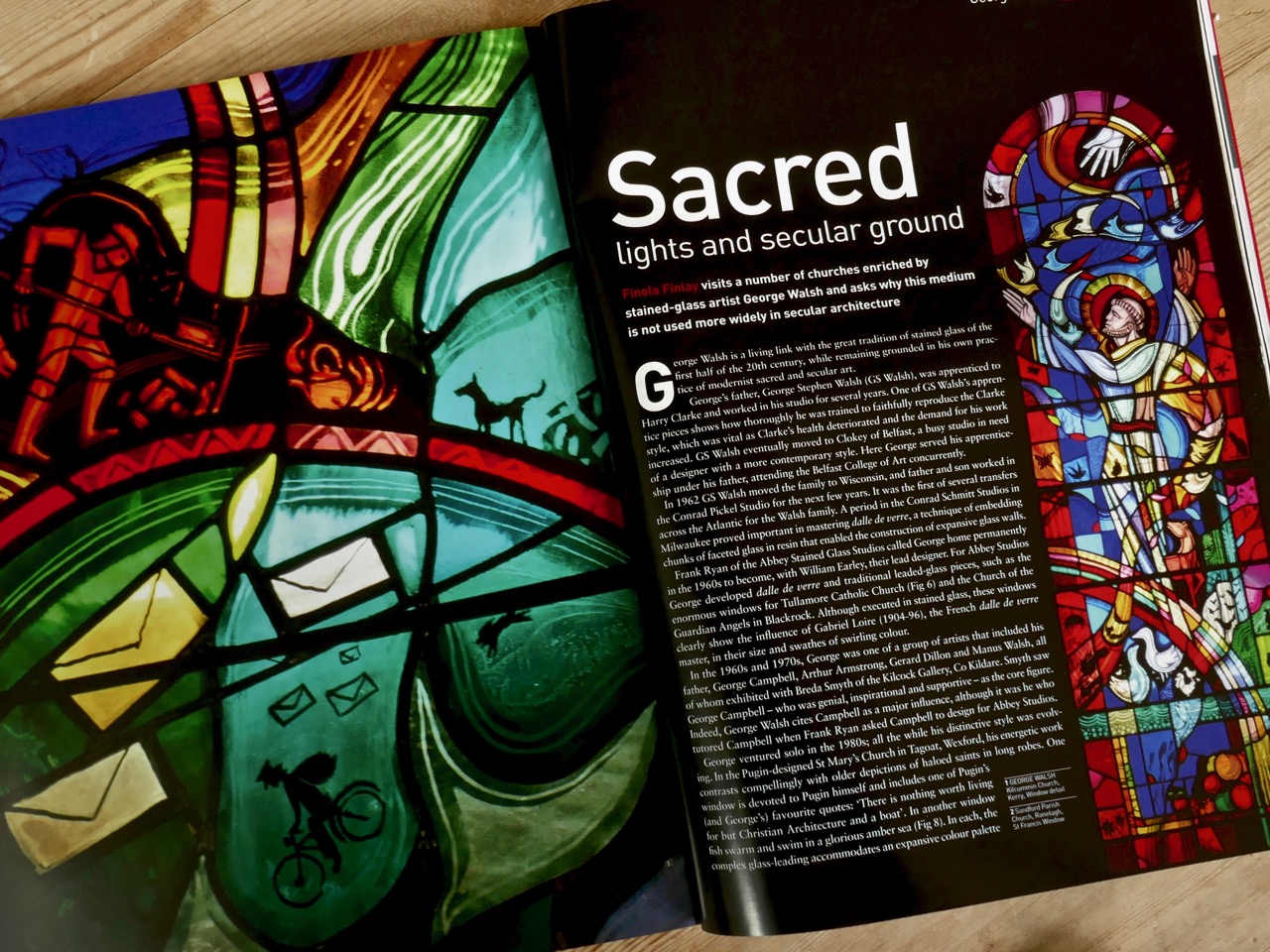

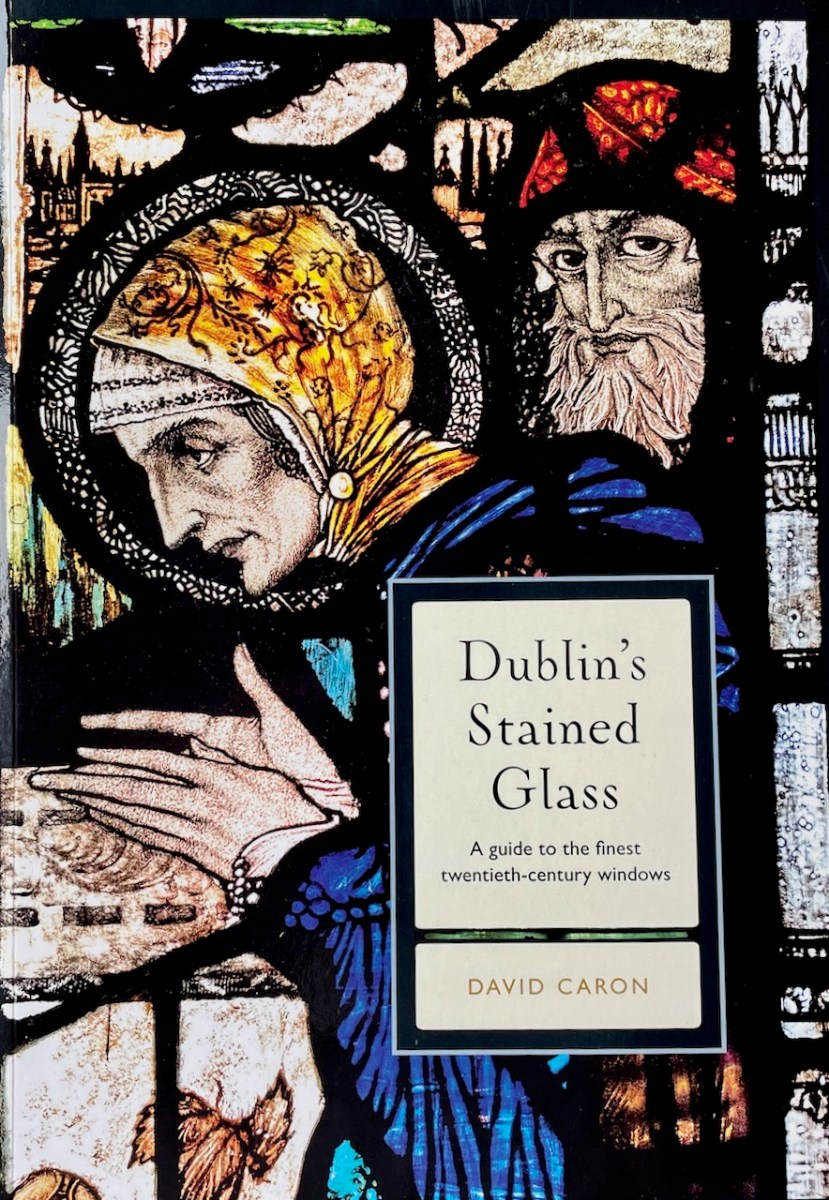

As my regular readers know, I write frequently about stained glass, and I was a contributor to The Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass. The editor and main writer of that volume was David Caron, and I previously reviewed his marvellous book (I called it a ‘miracle’) on the life and work of Michael Healy. Now comes his latest work, Dublin’s Stained Glass, a book about the best 20th century glass in Dublin Churches, stunningly produced by Four Courts Press. This book needs to be in your library!

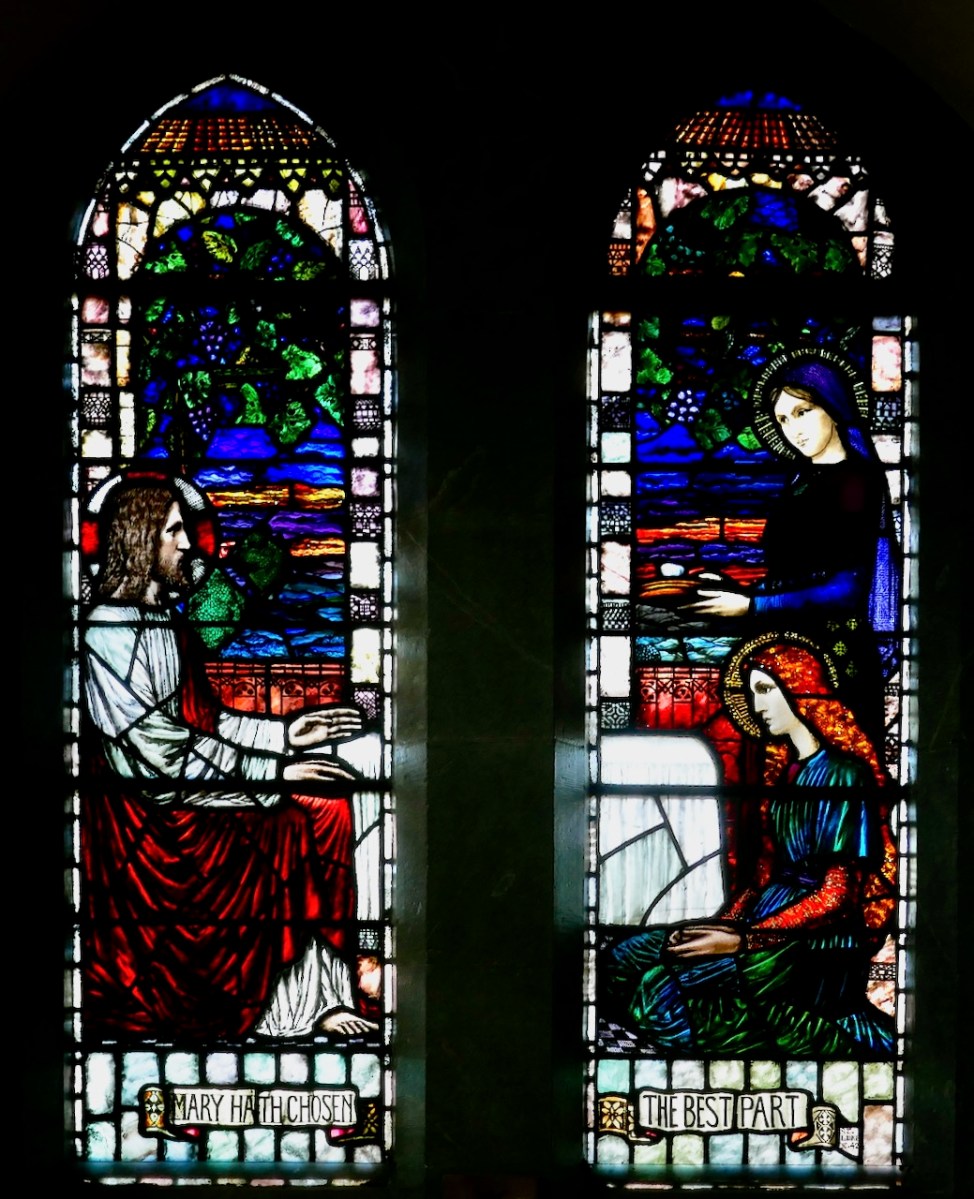

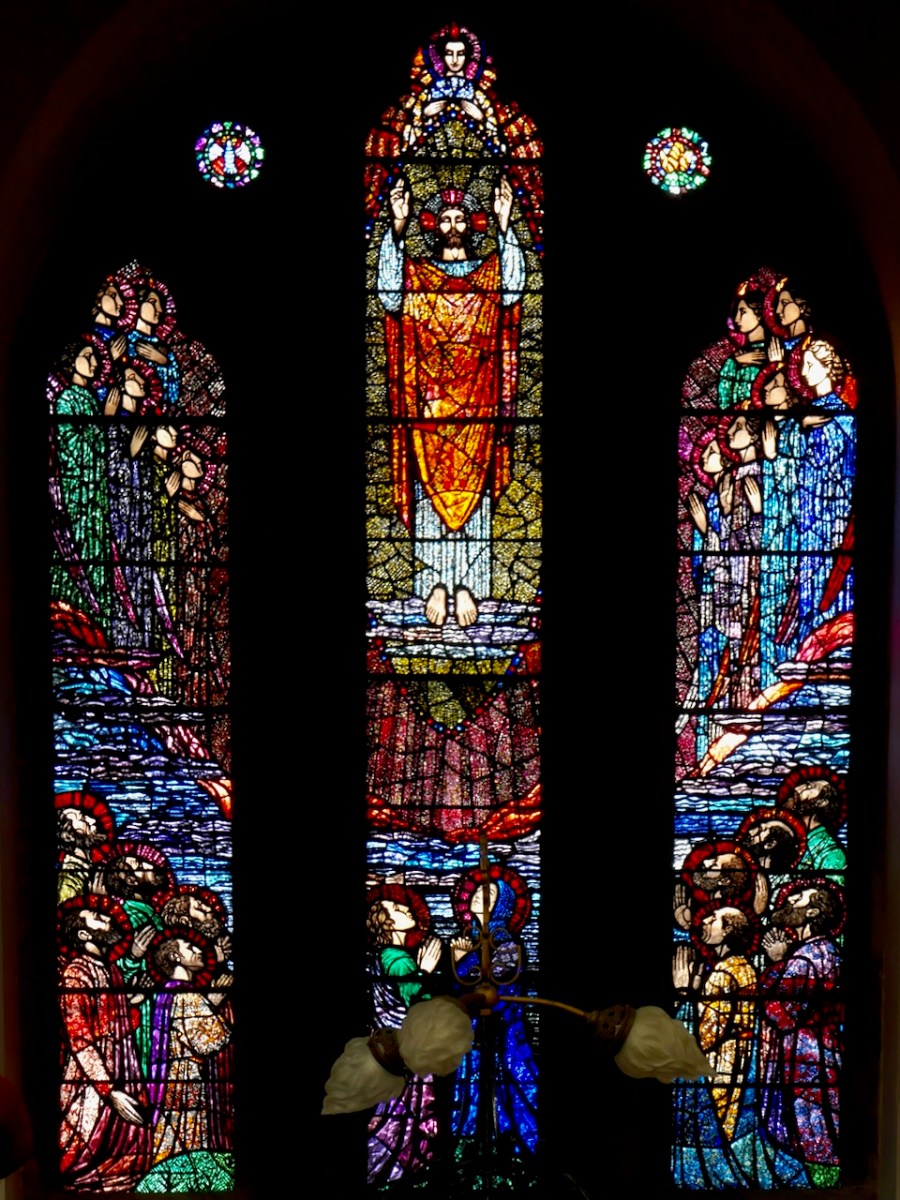

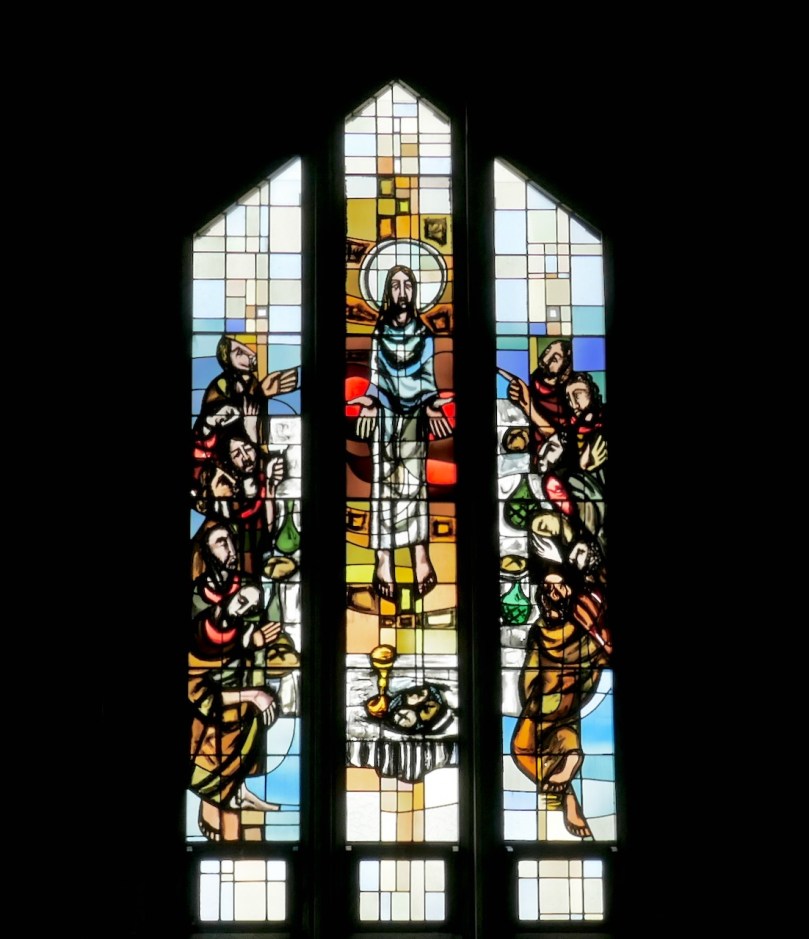

The John’s Lane church features in David’s Book, with a detail from the St Rita window. Here’s all of the narrative part of the window.

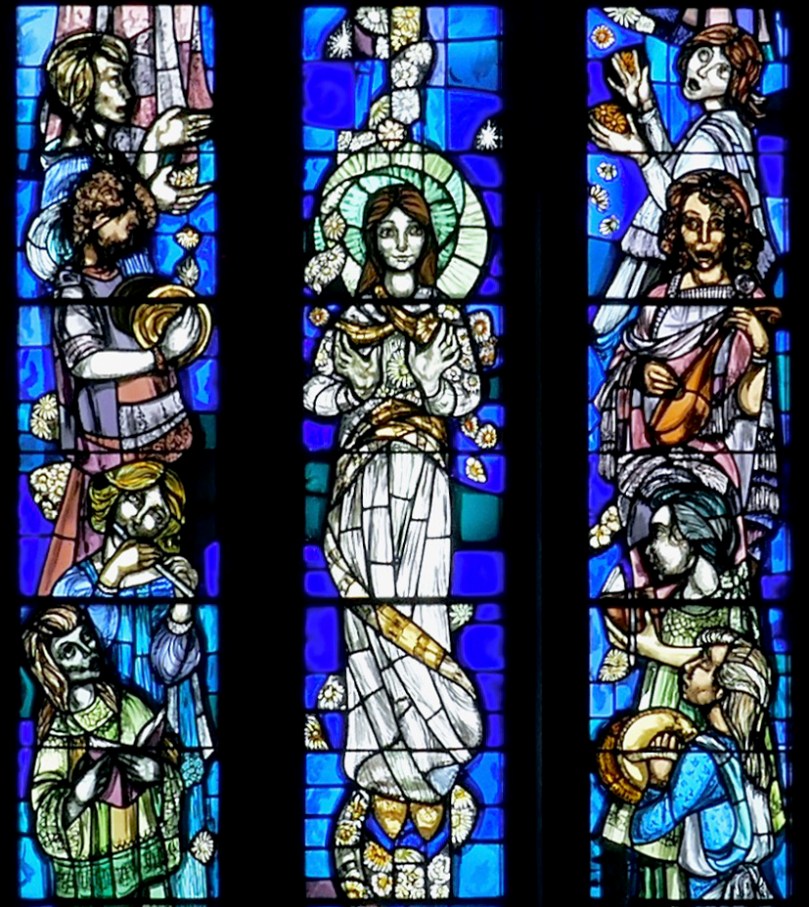

Here’s a statement you might not hear every day – the Catholic Church was the greatest patron of Irish artists in the 20th century. This is particularly true after Vatican II, 1962-65, the decrees of which included encouragement to use modern forms of architecture and art. But it is also true that the Church had the means to commandeer resources that were available to few private individuals in 20th century Ireland. The result of this is that the work of some of our best artists is public and easily accessible. While this book focusses on stained glass, David also points out where appropriate other example of fine art in churches (e.g. stations, altar furniture) as well as identifying the architects working to modernise or re-order our churches.

I have used my own photographs throughout this post, but they cannot compare with the magnificent photography by Jozef Vrtiel, David’s long-term collaborator and the single most talented photographer of stained glass in Ireland. This is truly a combined effort – David’s text and Jozef’s images complement each other superbly.

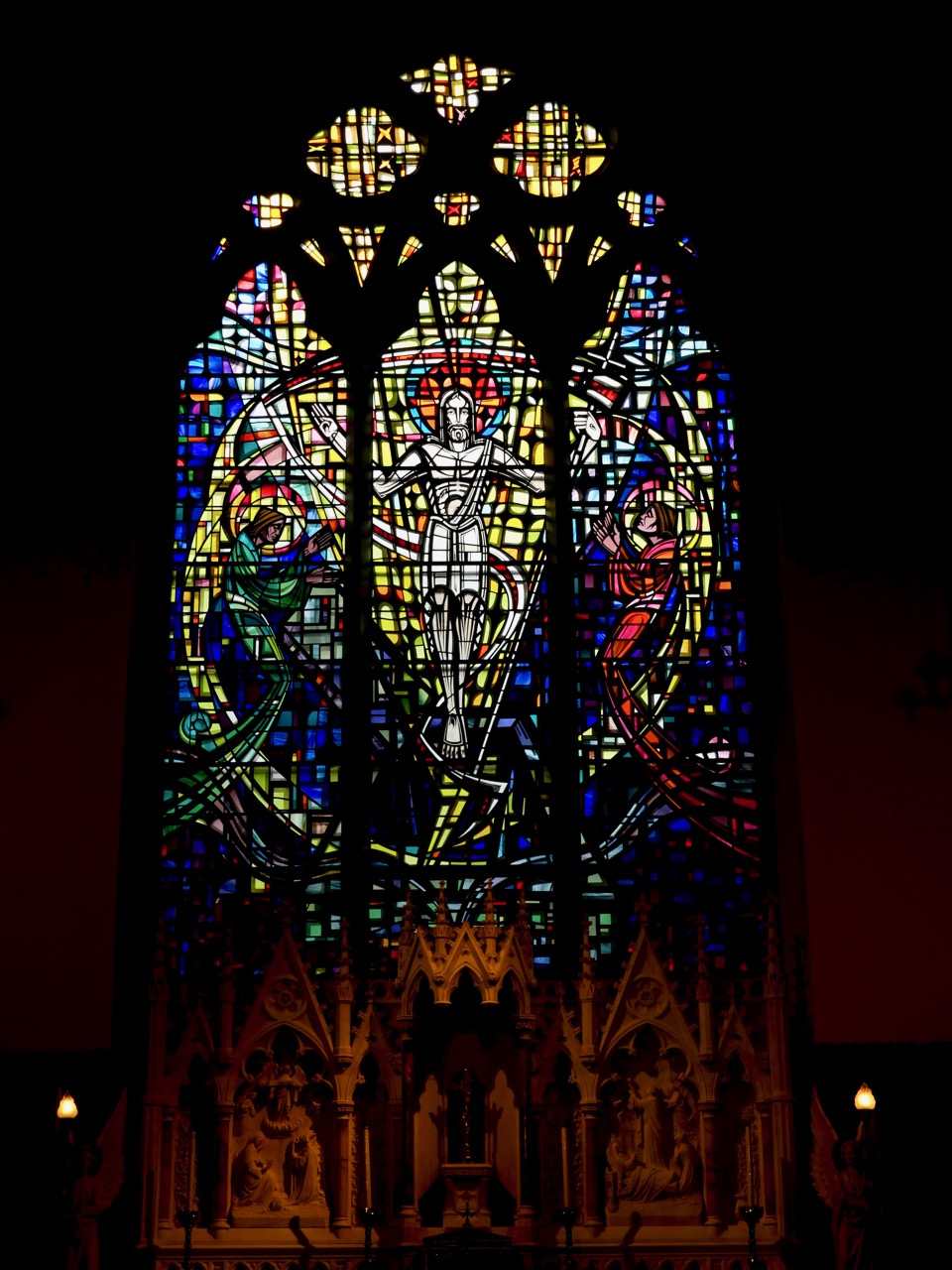

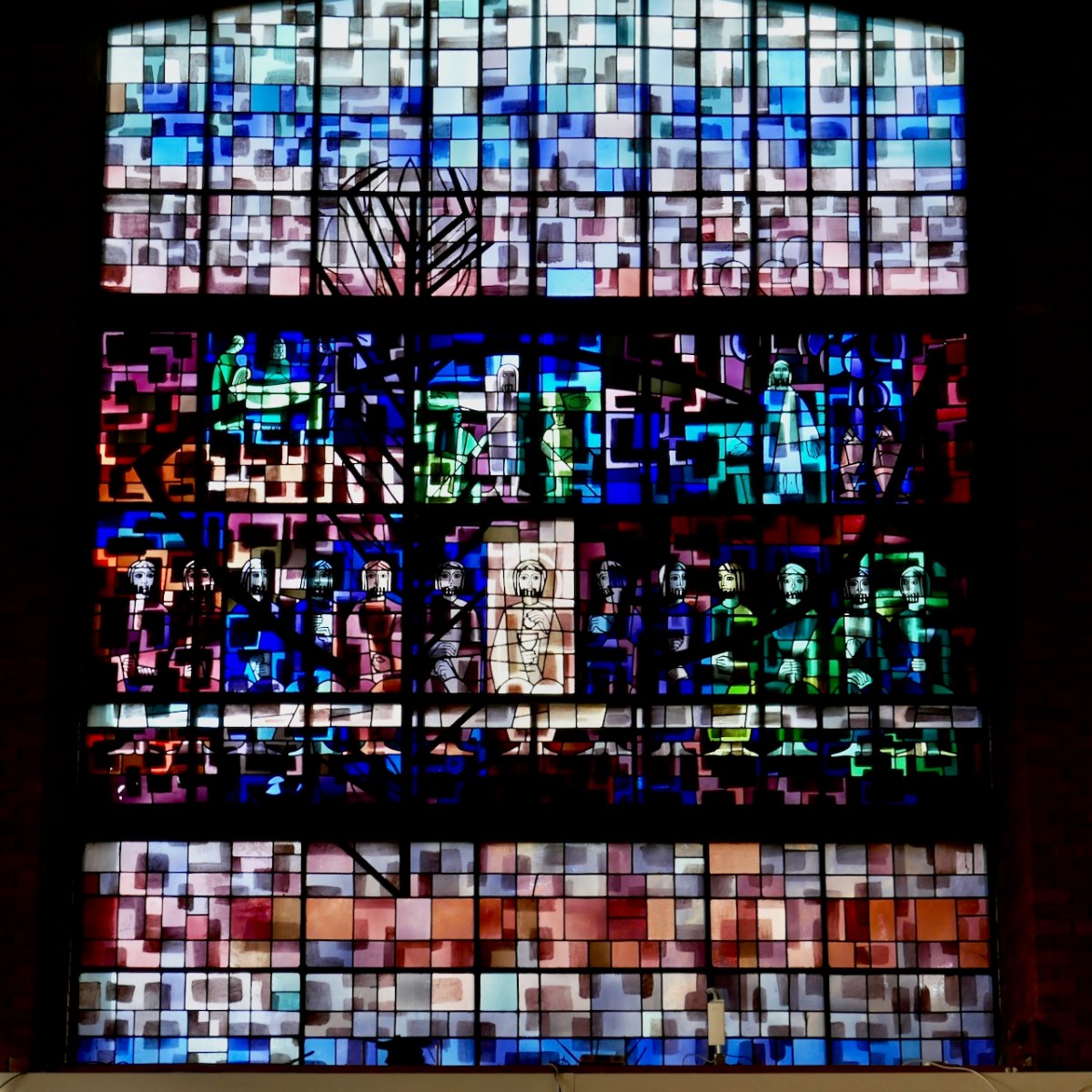

The book is laid out in sections: City, Dublin North and Dublin South (suburbs and county), encompassing thirty-nine locations. They are not all churches – Bewley’s on Grafton Street is included for its Harry Clarke windows (above, and above that), as well as the National Gallery with its excellent stained glass room, the Hugh Lane Gallery, home of Clarke’s Eve of St Agnes, and St Patrick’s Campus of Dublin City University, with its floor to ceiling expanse of dalle de verre by Gabriel Loire. This is a good example of a non-Irish artist included in the book. Gabriel Loire was French, and the internationally acknowledged master of the dalle de verre technique, in which slabs of glass, chipped round the edges to increase refraction, was embedded in concrete or resin, allowing for soaring walls of colour to be incorporated into the architectural scheme.

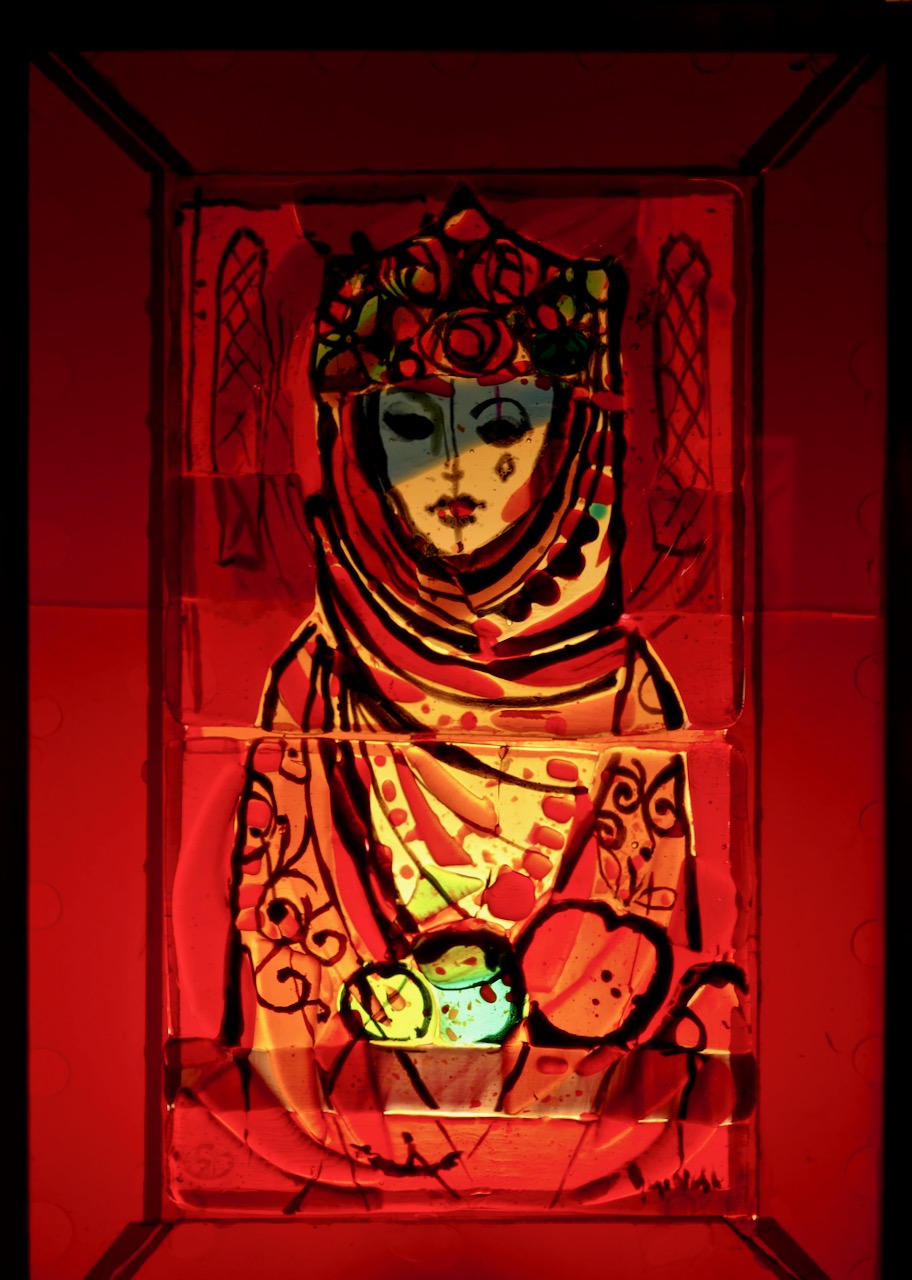

This little predella panel is at the base of The Blessed Julie window in Staunton’s Hotel on Stephen’s Green

But of course, mostly the stained glass is in churches. Catholic churches tend to be open much of the time, making them the easier option to visit. A little careful planning may be needed to visit non-Catholic churches. David gives the postal code for each location – very helpful as it works well with Google maps. Of necessity, schools, hospitals and other institutions had to be excluded since they are not publicly accessible most of the time.

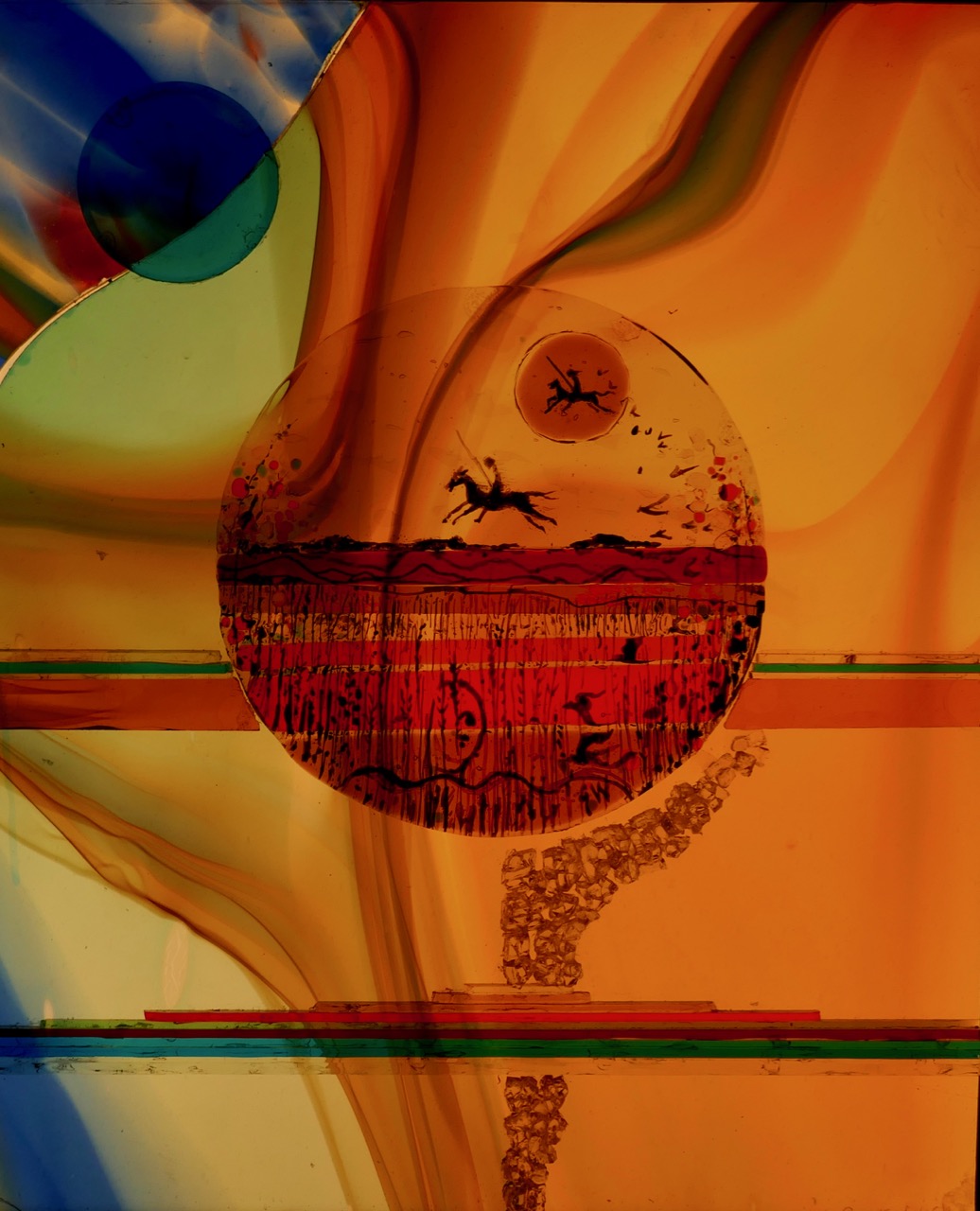

In the Dublinia exhibition this is George Walsh’s Trades window

In his introduction, David tells us:

During the 20th century Dublin’s reputation as a centre for stained glass excellence, both in terms of artistry and craftsmanship, was internationally lauded and is evidenced by the many orders placed by overseas patrons. Stained glass was the one area of the visual arts in 20th century Ireland that had an established school of the highest calibre, as distinct from singular talents such as Jack B Yeats and Eileen Gray. The highpoint for Irish 20th century stained-glass was the period from 1915 to 1980 and the leading figures were Harry Clarke, Wilhelmina Geddes, Michael Healy, Evie Hone and Richard King all of whom trained in Dublin, worked out of Dublin studios and so it is not surprising that the city has a concentration of first rate stained glass by them and many others.

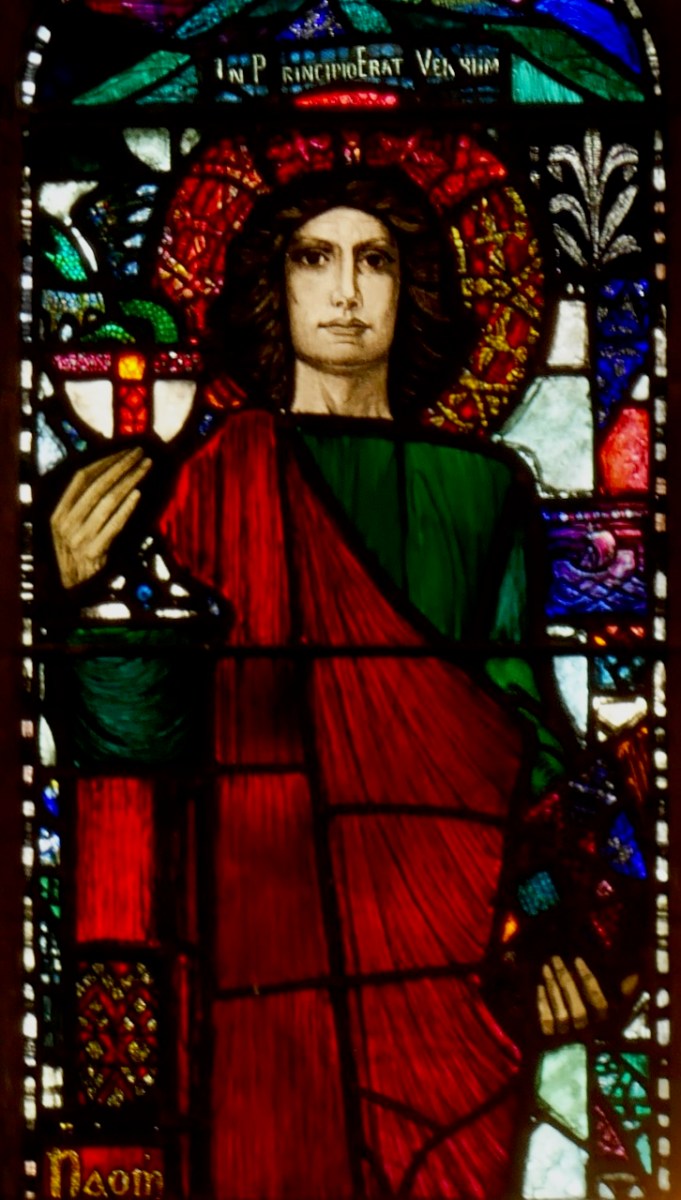

Evie Hone’s Head of St John at the National Gallery

I would add that stained glass was an area where both Irish men and Irish women could excel. Many of our finest stained glass artists were women and there has never been any tendency, as with other areas of artistic endeavour, to privilege the reputation of men over women.

Ballyroan Church of the Holy Spirit, with Murphy-Devitt’s stations laid out in narrative progression. This church also has paintings by Sean Keating

David starts with the architecture of each church, identifying the architect or firm, and describing its main features and influences as well as dates of construction and/or modification. As he says, if one were to visit all or many of the locations in the book, one would get a comprehensive overview of the story of twentieth-century Irish stained glass.

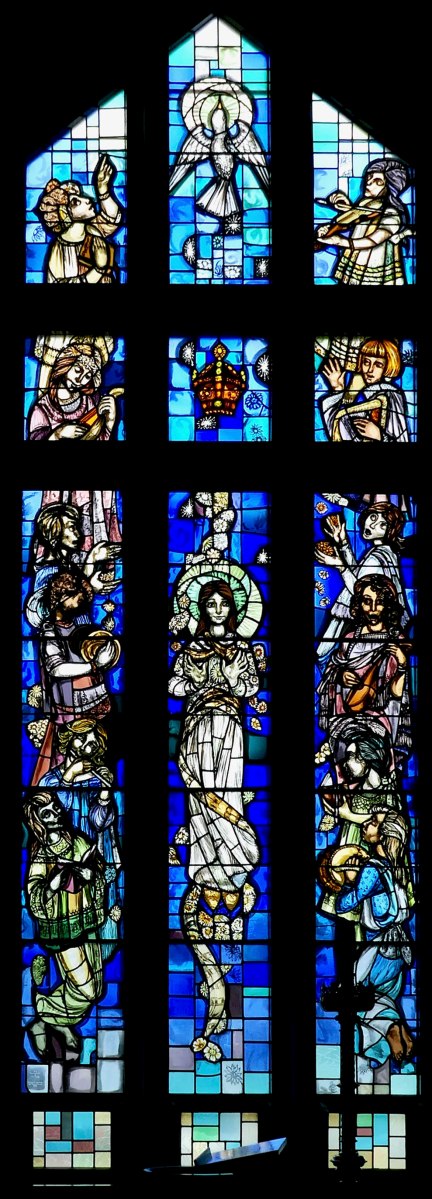

Let’s take one example – the church in Ballymun, Our Lady of Victories, one of the first batch of six churches in the Dublin Diocese that were built in the five years immediately after Vatican II, and which take into account the Guidelines of the council. Stepping into this church, as I did for the first time in May this year, is an immersive experience. First of all, it’s enormous – a reminder that in the 60s we were building Catholic churches which could accommodate thousands of congregants over the course of several masses every Sunday.

Secondly, you are immediately aware of being bathed in light and colour. There is a ‘lantern’ surrounding the central altar and this is the work of Helen Moloney. Here is David’s description:

Although it comprises eight sides or ‘windows’ (each composed of five panels), Helen Moloney created just two different designs for the windows; from these she made four different colour versions and these were duplicated to create the eight different windows. Despite the fact that there are essentially just two designs and she chose a deliberately restricted colour palette, this repetition is hardly apparent and instead one experiences an almost overwhelming sense of intensely zinging complimentary colours enlivened by punchy graphic symbols. Moloney used only the best of mouth blown glass in a selection of rich colours including red, blue, yellow, purple, violet, orange, green, and aquamarine, and although she has included different shades of these, mostly they are full strength from maximum visual impact.

The second artist with work in Our Lady of Victories is my own favourite, George Walsh, at this time still working at Abbey Studios. The stations are by him, in an innovative technique using copper sheets, with details cut into them in the manner of a stencil (above). David comments, The effect is graphic and reduces the Stations to their essence. David points out that a rare feature of these Stations is the inclusion of a fifteenth station, the Resurrection. Walsh also has a St Joseph, a St Patrick and a Madonna and Child in the church.

Finally, Sheila Corcoran created a series of symbolic windows at ground level (above), representing the Evangelists and other sacred subjects. Neither Moloney nor Corcoran included any painting, relying solely on glass of different colours and shapes to create their images – an unusual choice for the time and very effective in this context.

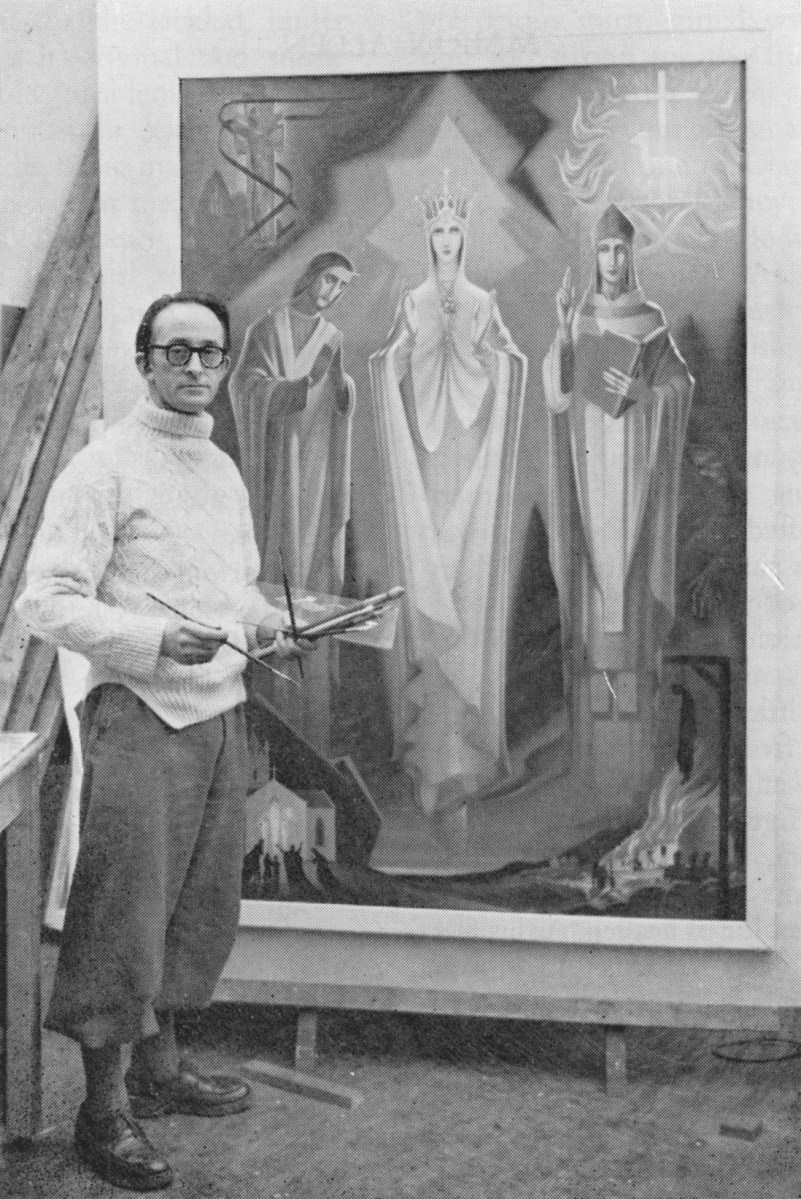

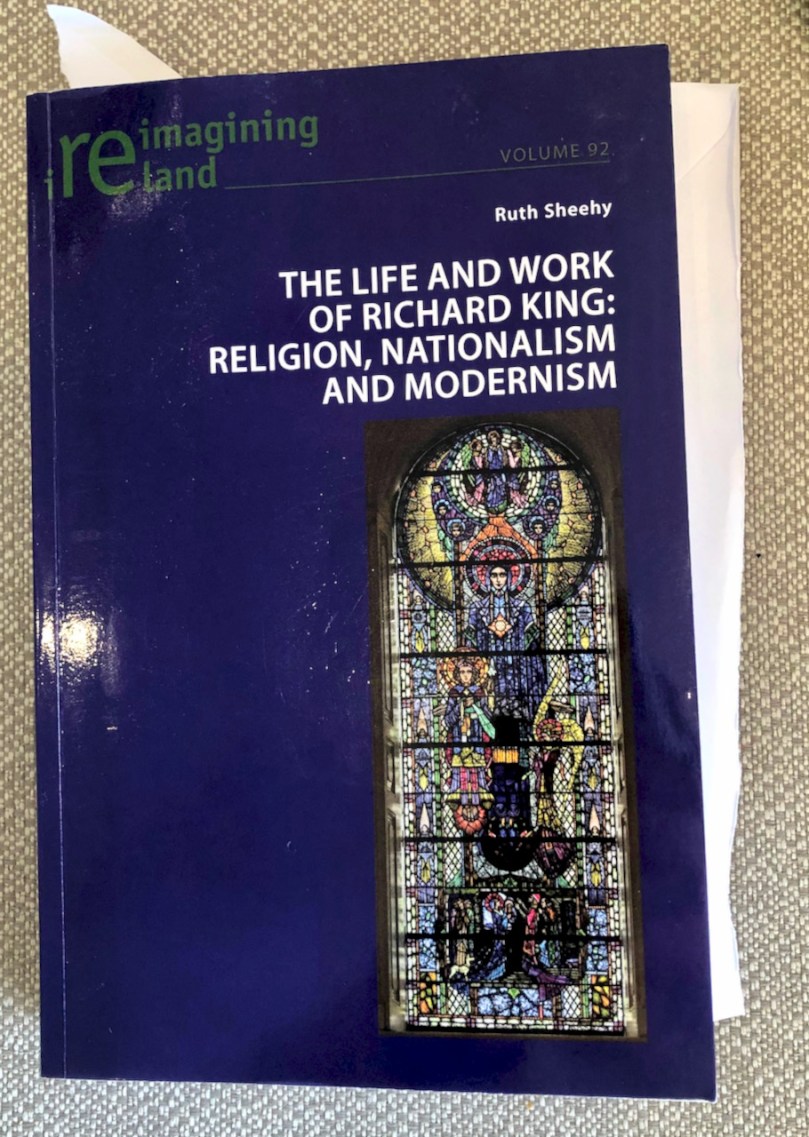

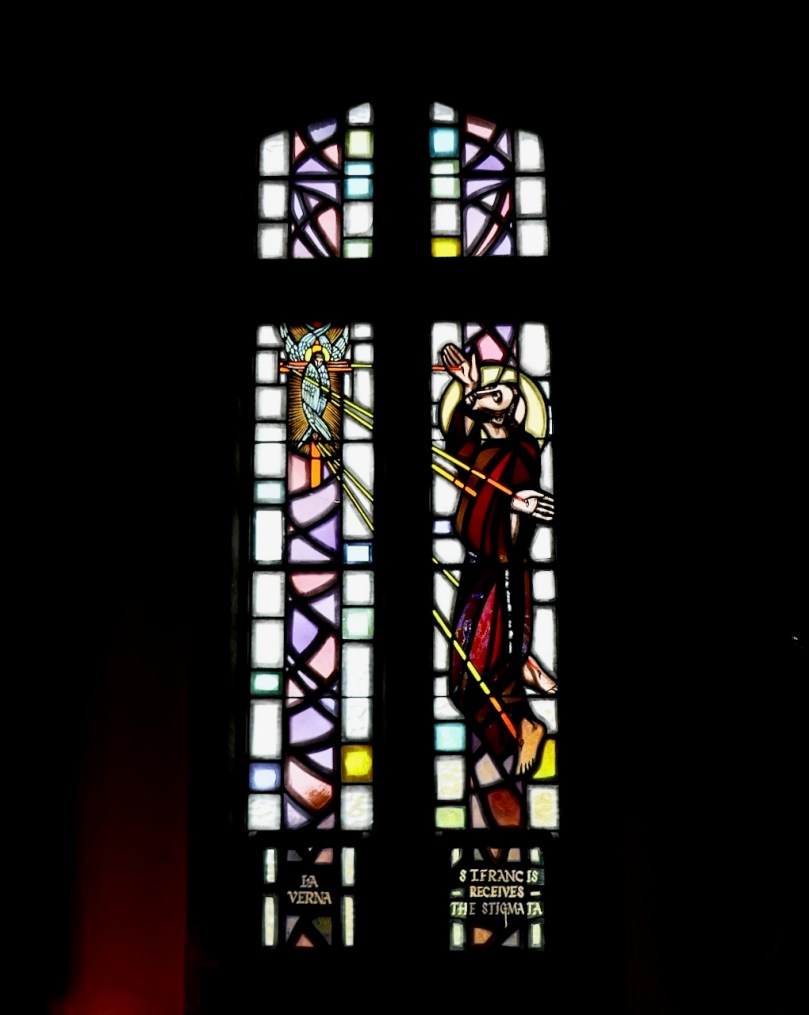

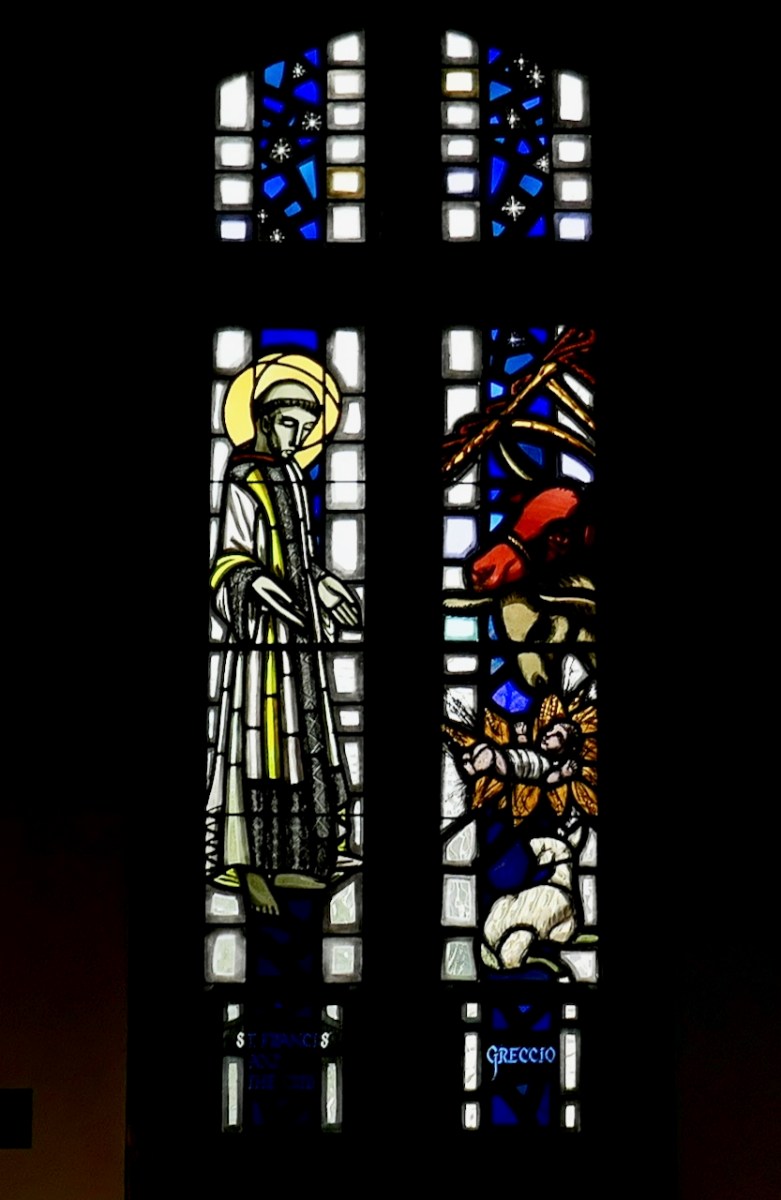

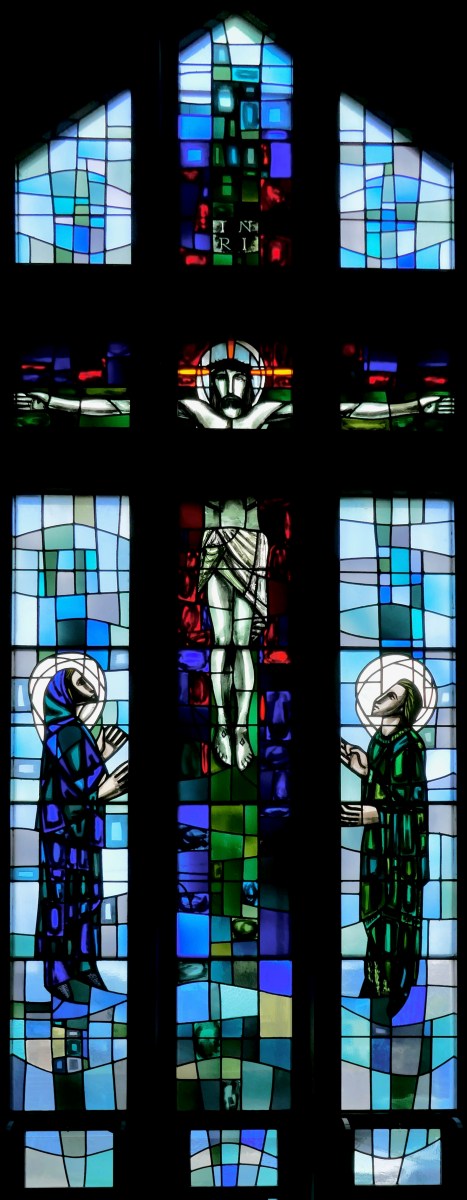

Moving to South Dublin, I cannot resist a visit to Greenhills, to the Holy Spirit Church on Limekiln Lane (above). I visited this church two years ago in the company of Robert, David Caron, Paul Donnelly (the Harry Clarke Studios expert) and Ruth Sheehy. We were thrilled that Ruth – whose work on Richard King has pride of place in my library and whose expertise I documented once before in my post Stained Glass Detectives – and a Find! – was able to talk us through the window, illuminating each part of it, and expanding on Kings’ style and colour choices. My topmost photograph in this post was taken as she led us through an erudite tour of each element.

King was aided and abetted by the Murphy Devitt Studios. Johnny Murphy worked with King to provide all the surrounding glass, in harmonious shades and using the same mouth-blown glass. He also designed the dalle de verre windows at ground level, while Peter Dowd, Roisín Dowd Murphy’s brother, was responsible for the wonderful bronze doors. The day we were there a choir was practising for an upcoming concert. The sensory effect stays with me still.

A Harry Clarke panel of St Paul on the road to Damascus, from the Sandford Road Church. This is not one of the churches included in the book, which just shows what difficult choices had to be made to stay within the page-count.

I have only highlighted two churches, both dating to the 60s – and neither of them contains a Harry Clarke! Rest assured that this book contains lots of Clarkes – at least 6 of the locations contain Clarke windows, as well as those and others containing the work of his Studios artists after his death. You will also be happy to see Evie Hone, Michael Healy, Wilhelmina Geddes, Hubert McGoldrick, Catherine O’Brien, Patrick Pollen and several others.

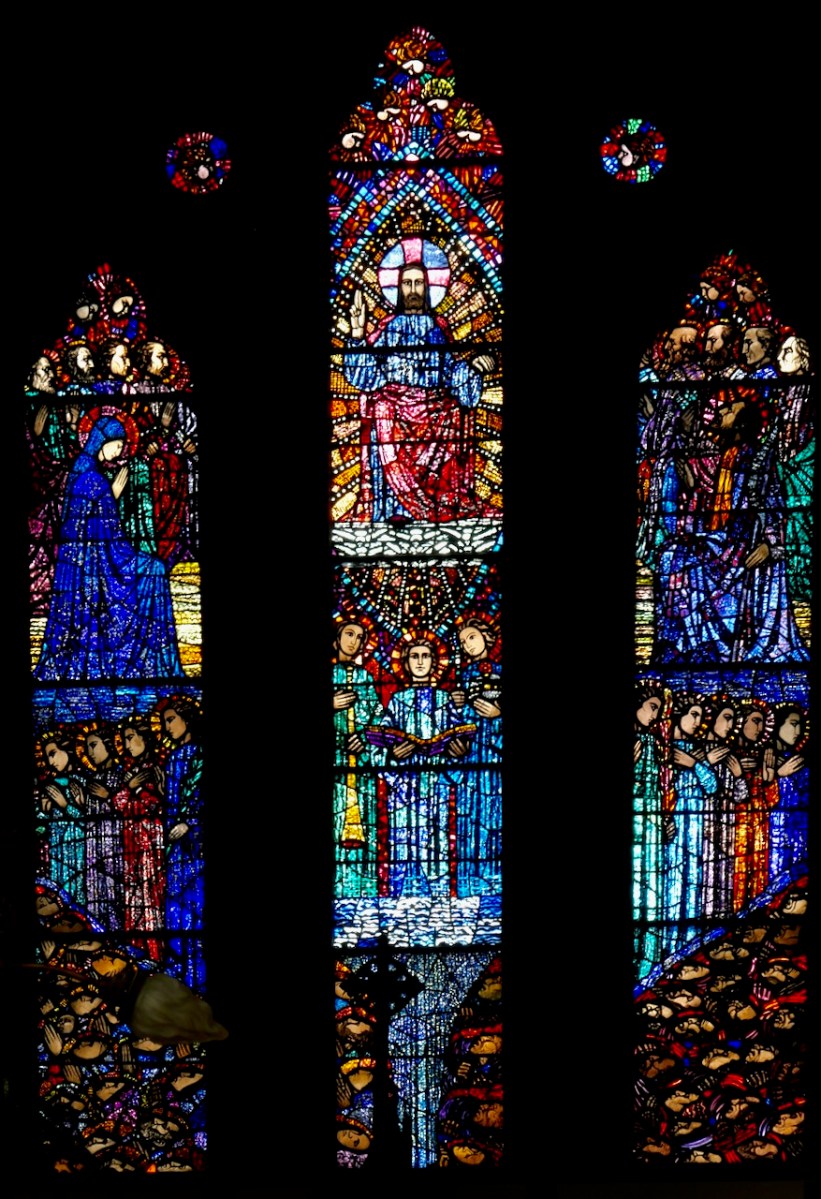

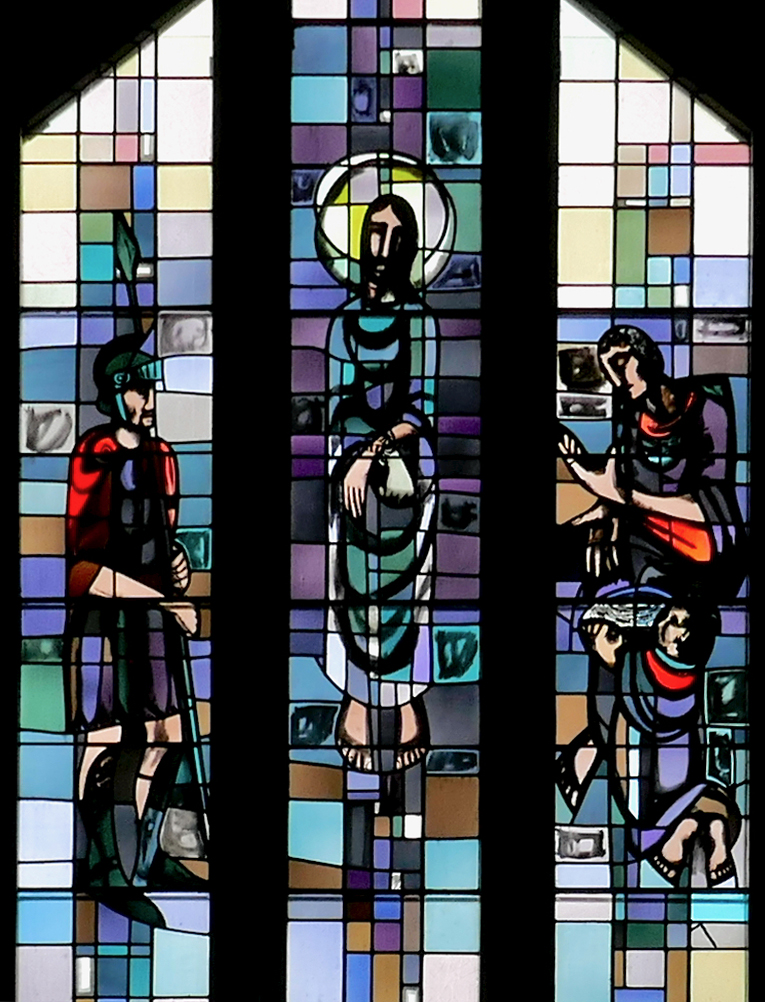

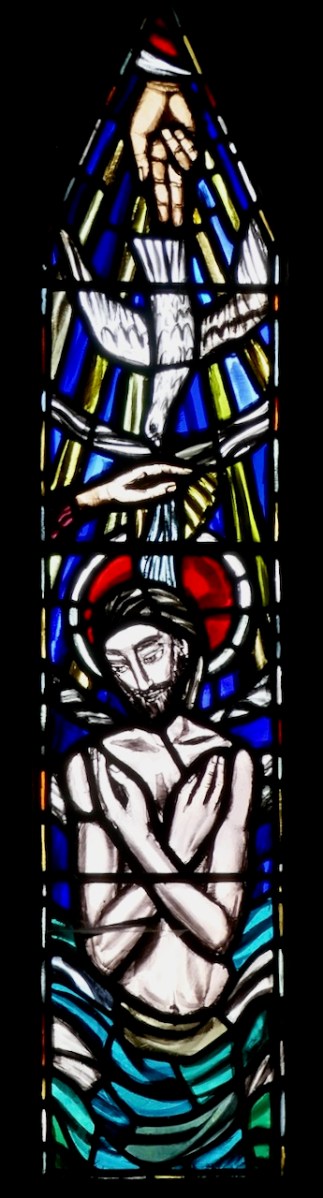

Patrick Pollen’s Baptism of Christ from Lusk

What is does not contain (with a few key exceptions) are productions by unnamed artists working in the large studios (Earley, Watsons, etc), nor windows from the mass-production houses such as Mayer of Munich.

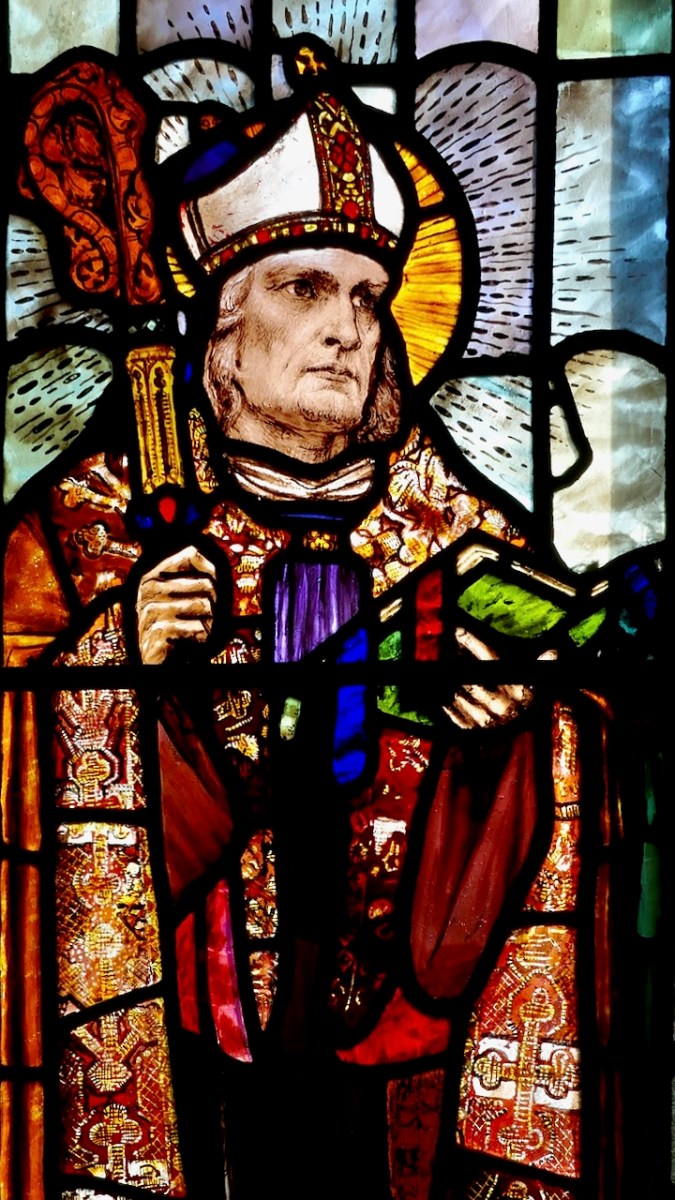

Harry Clarke’s St MacCullin, also from Lusk

There are, as I have said, 39 locations in the book, but David would be the first to admit that if he were not constrained by page- and word-count he would have included several more. So let me add a couple that are so well worth visiting, even though they had to be left out of this volume. While at Lusk, for example, David suggests a visit to nearby St Maur’s in Rush and I concur – George Walsh’s series for this church typical of his mature style (below). Another place to see Walsh’s work is the Church of the Guardian Angels on Newtownpark Avenue in Blackrock.

St Mary’s Church in Sandyford has early Netherlandish glass – and yes, that is NOT 20th century, but it’s one of the few places to see it up close in Ireland. St Laurence O’Toole Church in Kilmacud has a huge and very stylised panel by Phyllis Burke (below). Sandford Road Church of Ireland has a Harry Clarke St Peter and Paul (see the illustration fourth up).

I’ve written about a few of the churches in this book, so you know I have other favourites too. St Michael’s in Dunlaoghaire, for example, and one of the several Harry Clarke windows in St Joseph’s in Terenure. I am sure you have your own favourite Dublin Churches – any additions you’d like to make to my short list, dear Readers?

This is one of a set of stations made from antique glass and polished granite, done by George Walsh and Willy Earley for the Clarendon St church

Grand so, you have all you need now for some ecstatic wanderings around Dublin Churches. I leave you with our own ecstatic wanderings – as a bookend to this post, here we are in Greenhills, quite in awe of Richard King’s and Johnny Murphy’s enormous window. Left to right is Paul Donnelly, David Caron, Ruth Sheehy and Robert.