Last week I left you at the threshold of the Castle and Friary on Sherkin, promising to come back to them this week. As I read up about them, though, I realise that each deserves a post of its own, so we are going to look at the Castle first.

What we see now is a pale shadow of what the castle looked like in the 15th century. The Friary was built in 1460 and the castle, or tower house, around the same time, maybe a few years later.

The builder of both was Florence O’Driscoll, chief of the wealthy and warlike O’Driscoll clan, whose headquarters were in Baltimore. It was one of a series of O’Driscoll Castles, which also included Oldcourt, Rincolisky, Lough Hyne and Ardagh, as well as Dún an Óir on Cape Clear, Dún na nGall on Ringarory Island. If you have not already done so, take a look at my posts on Dún an Óir, the Fort of Gold, on Cape Clear Island – it will give you some background into the operations of the O’Driscolls and their network of Castles. And this page has a list of all my castle posts and browsing them will explain all the terminologies, such as bawn, or raised entry

Like the O’Mahonys to the west of them, the O’Driscolls derived their income from control of the waters of the eastern side of Roaringwater bay – and specifically control of the fisheries. And that income was considerable: enough to build all those castles, to mount a fleet of ships, to import the finest wines from France and Spain, and enough to endow a friary where Franciscans could pray for the souls of Florence and his descendants so they could be assured of safe passage to Heaven.

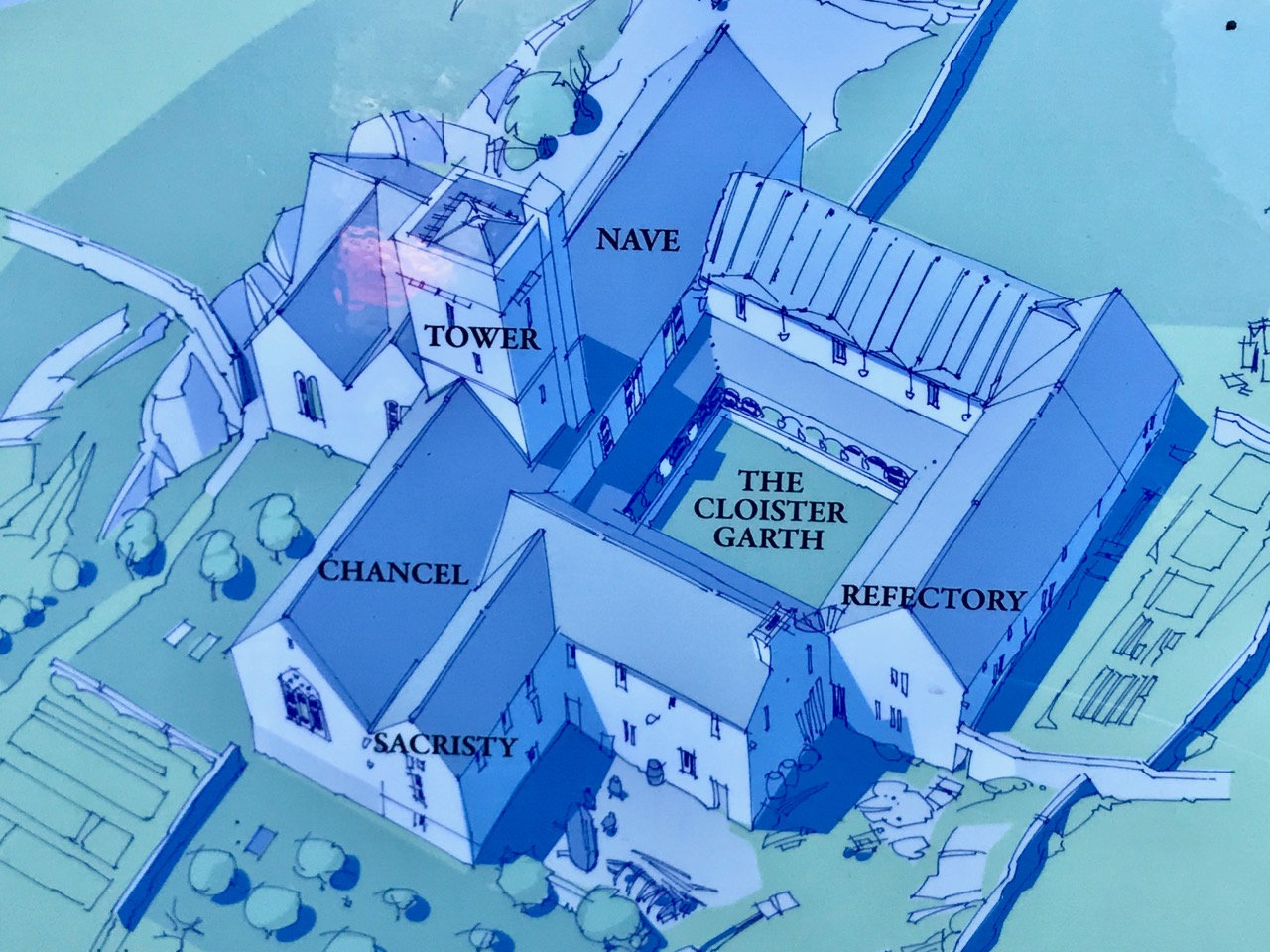

Dún na Long (Fort of the Ships) was strategically sited indeed. It had a good view across to Baltimore but more importantly of the entrance to the inner waters – anything that sailed between Sherkin and the mainland was immediately spotted. It was also very close to the Friary, and could defend it if necessary – although that didn’t quite go according to plan, as can be seen from the top photo, a picture of the Battle of the Wine Barrels that took place in 1537 between the O’Driscolls and a force from Waterford, come to take their revenge on the O’Driscolls for their constant raiding of the cargo ships.

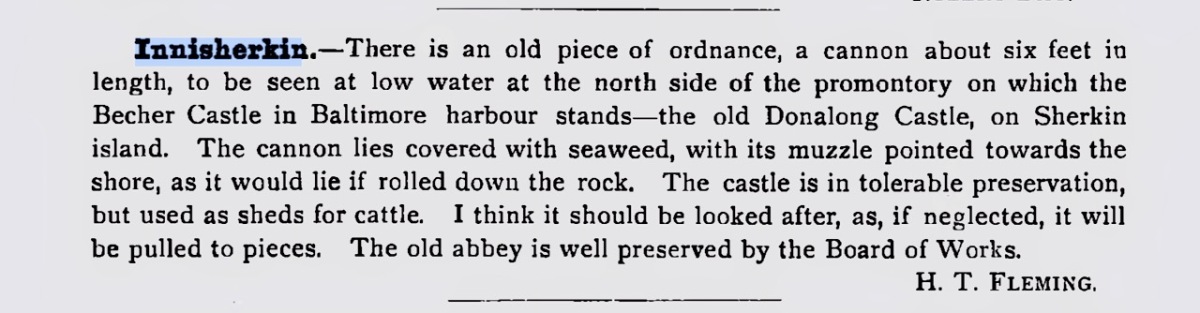

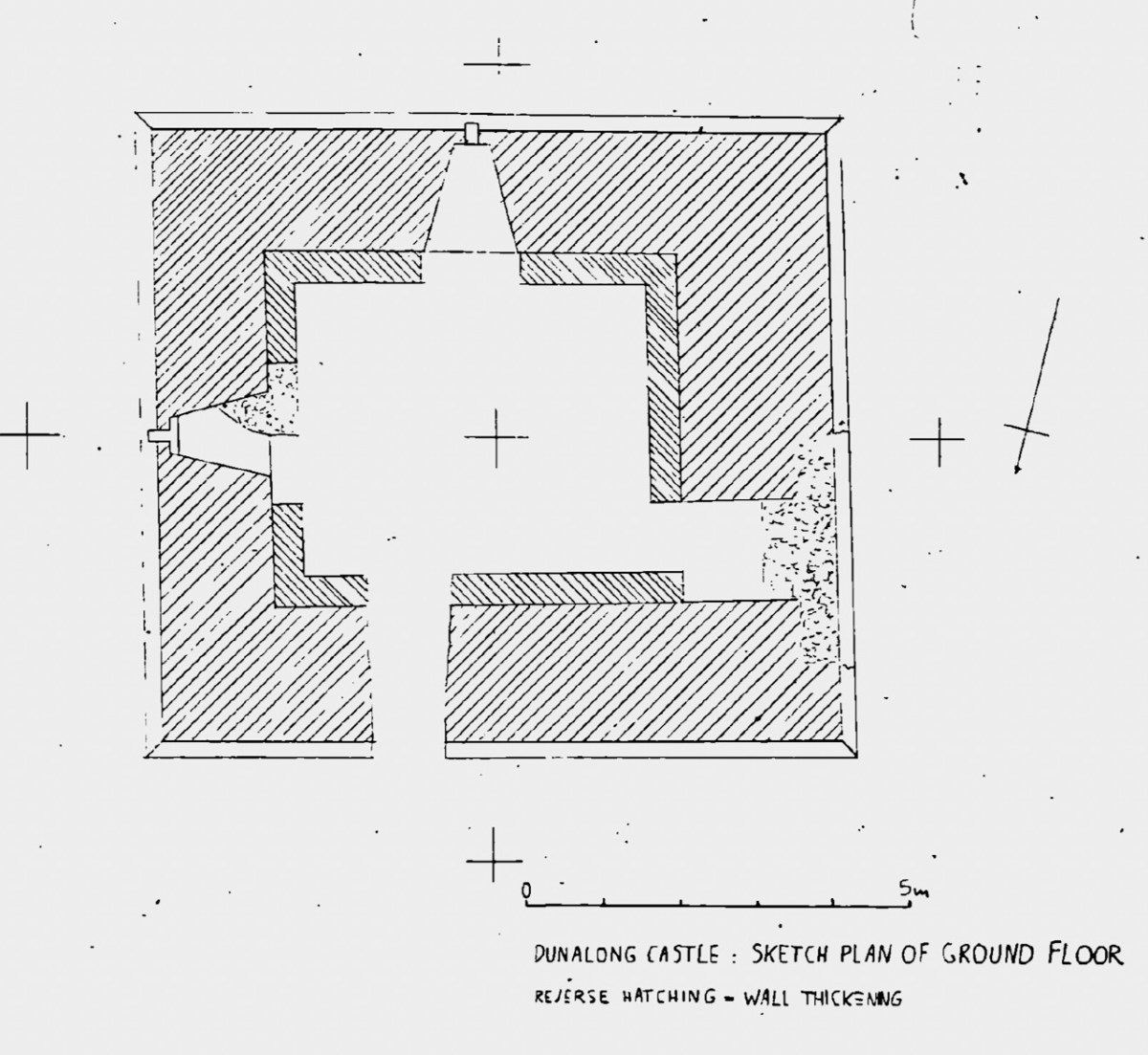

Let’s take a closer look at that drawing to see how the artist represents what Dún na Long looked like originally. Due to the shape of the promontory it occupies a long and narrow space, rather than the square or rectangular area we have come to expect, of a tower house surrounded by a Bawn wall (see Illustrating the Tower House). So the bawn wall is there, but elongated to run the length of the promontory. The tower house itself occupies a central position and there is one corner tower on the landward end. Note that the artist shows a huge cannon on the seaward end of the castle. This would have been unusual for an Irish castle, but there is some evidence for it. In the 1895 Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, a Mr H T Fleming notes this:

Wandering around the ruins, it is possible to see the remains of what was once there. The central tower now stands to only two stories. There is an entrance on the ground level, but this is an enlargement of what was originally a window ope. The actual raised entry was in the west wall – you can see it in the photograph below, although it has been much altered. It probably looked like the ground floor and raised entry configuration at Dunmanus Castle.

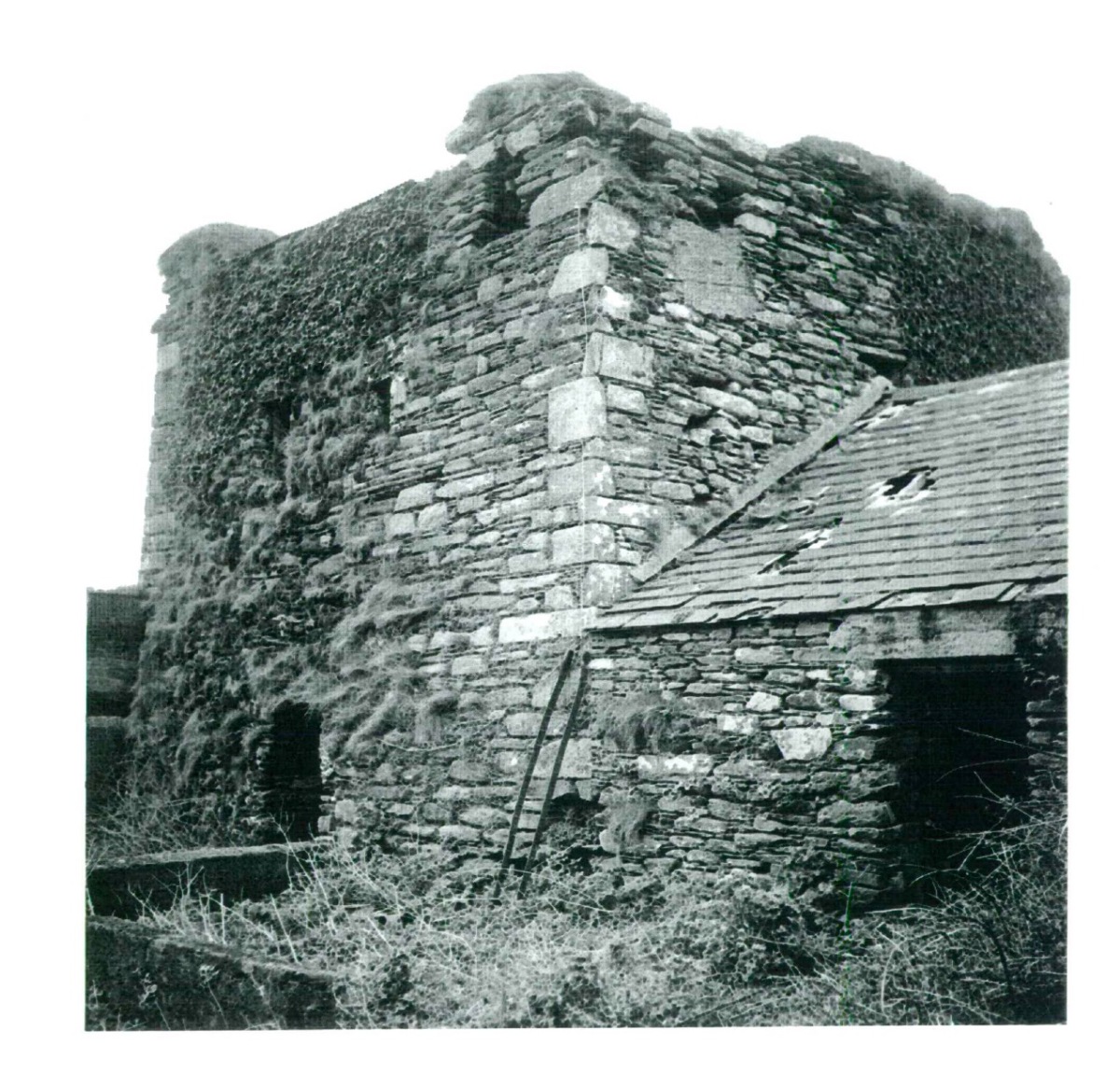

There is a pronounced base batter, Samuels, in his Tower Houses of West Cork, provides a sketch plan which shows how impressively thick the walls are.

When he was doing his field work, in the 90s, there was still a roof on the pig shed built onto the west wall and he provides this photograph of how the central tower looked at that time.

The small corner tower can be clearly seen in the photo below as Amanda is wandering down to the castle.

That tower occupies the corner position on the bawn where the wall that runs along the landward side meets the wall that runs along the sea, closest to the Friary.

In the sketch, you can see the Waterford force has made its way onto the land and is firing at the castle from that side. What is left of this wall has been extended using modern concrete block.

After the battle of Kinsale in 1601, the current clan chief, another Finghín, handed over the castle to the Spaniards, who in turn surrendered it to the English under Captain Harvey. Since that time it has led an anonymous and ignominious existence as a cattle or pig shed.

Nowadays, the site is much tidier than when I have visited in the past. A picnic table provides a pleasant spot to look out over the sea and think about what life was like in this castle in the 15th and 16th centuries.