The Franciscan Friary on Sherkin Island (also called the Abbey) was established by Fineen (Florence) O’Driscoll, chief of the wealthy O’Driscoll clan, which had its headquarters in what is now Baltimore, but which, in the middle ages, answered to the name of Dún na Séad – Fort of the Jewels (how’s that for flaunting your wealth?). We know this because Fineen applied to the Pope himself for permission to found a friary. The Pope was Nicolas V, here seen in his portrait by Rubens. Although he was only Pope for eight years he was highly influential and responsible for many church innovations (such as the Vatican Library) and buildings (he started St Peter’s Basilica). He’s certainly giving Rubens the side-eye.

Ann Lynch, who excavated the Friary between 1987 and 1990 (source of much of the information below) tells us that Nicolas, despite being so busy in Rome,

. . .in 1449, mandated Jordan Purcell, bishop of Cork, his dean, and a canon of Ross to license and to found a friary in his territory in honour of God, St. John and St. Francis. . . This reference is thought to refer to Sherkin Island (also known as Inis Arcain) and the licence explicitly states that the friars are to be under the jurisdiction of the Observant movement. There is no reference to building the friary however until 1460-2 when the founder is given as Florence O’Driscoll.

The Franciscan Friary on Sherkin Island, Co. Cork, Excavations 1987-1990,

Ann Lynch,

Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, 2018, 55–127

The Observant Movement aimed to restore the order’s focus on poverty, simplicity, and communal living as originally envisioned by Saint Francis. They did indeed seem to have lived a simple life – the only comfortable room in the place, and one use for communal living, was the chapter house, below.

The siting of the Friary, close to Dun na Long Castle (see last week’s post) was not unusual in medieval Ireland, apparently. The castle was supposed to provide protection for the Friary, while the Friary afforded spiritual benefits to the castle inhabitants and the O’Driscoll chiefs. However, as we have seen last week, this didn’t go according to plan. The Waterford men sacked the castle in 1538 and plundered the Friary, setting it alight, and leaving it badly damaged.

They also made away with the Friary bell, as well as some chalices and other valuables. Below is the base of the famous Timoleague Chalice, probably very similar to what was stolen. You can read the story of the Timoleague chalice here.

While the Friars fled for a while, they did return and lived at the friary until the last of them, Fr Patrick Hayes, died sometime after 1766. The Bechers took possession of it at that point and held on to it until they handed it over to the Commissioners of Public Works in 1892. It has been in the care of the State since then.

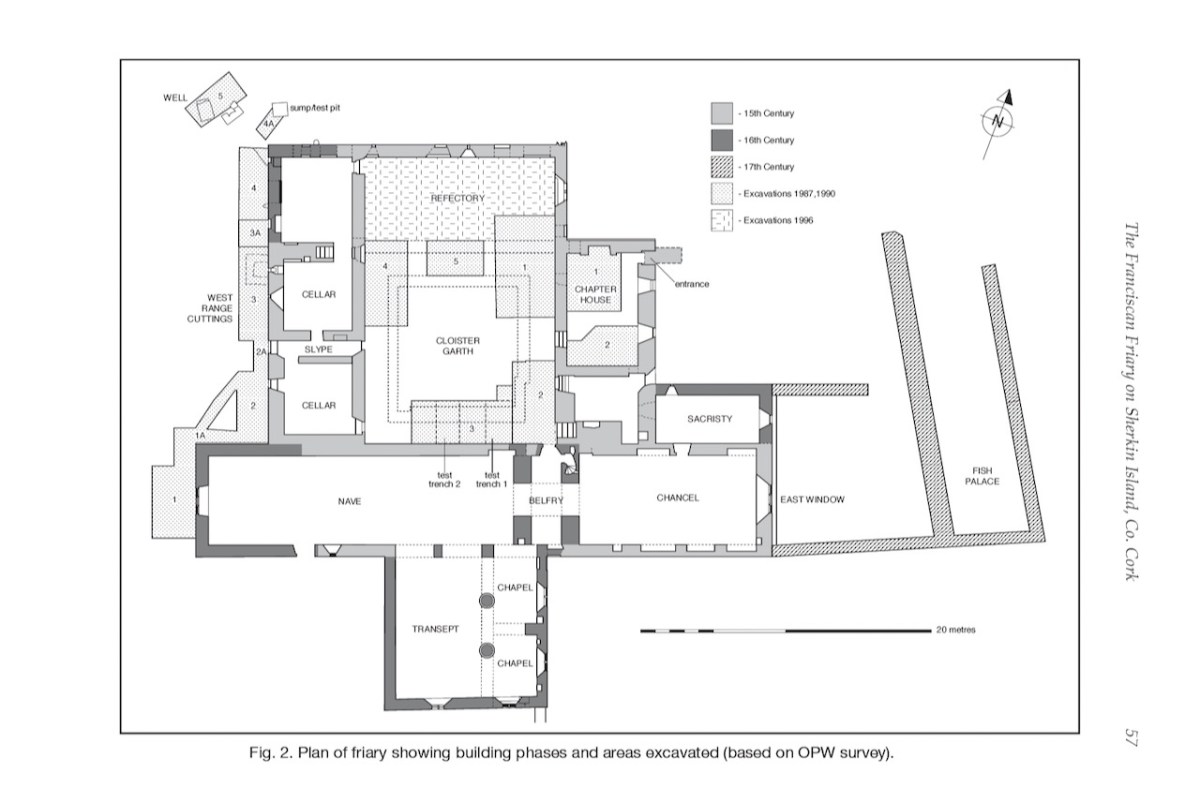

In form, the Friary is fairly typical of Franciscan houses in Ireland, with a long nave and chancel church, a bell tower, a cloister, side chapels, and a chapter house and refectory.

The nave and chancel run slightly north of east-west, due to the lie of the land. The West window has three lights and attractive tracery. We know that these would have contained stained glass, since fragments were found during the excavation, but we don’t know what they would have depicted. One of the charming features of this window are the heads – two still present although the one at the apex is too worn to make out, and a third indicated by a gap at the base of the hood moulding.

I am tempted to see a female saint in the one head that is still fairly complete. After all, St Mona is the patron saint of Sherkin, so why would it not be her?

The tower or belfry, situated between the nave and the chancel, is a familiar feature of Franciscan Friaries – we see the same thing (although on a larger scale) in Timoleague.

The base of this Sherkin tower has a little decorative carving – a very welcome note of frivolity in what is overall a plain building. Although, of course, we do not know how it was decorated: it may have had frescoes and painted walls and have been quite colourful, although generally the strictly observant friaries were not highly decorated.

The chancel (the inner sanctum) also has an eastern three-light tracery window, identical to the one at the west end. There are various niches in the walls in the chancel, and I am wondering if one of them might be an Easter Sepulchre. I have just been learning about these in the latest Archaeology Ireland magazine, in a fascinating piece by Christiaan Corlett. You can read more about them here. In essence they were resting places, from Good Friday to Easter Sunday, of the crucifix, the Host and various other sacred elements, all of which would have been contained in a carved box, which was then deposited in the niche. This niche certainly fits the bill, except that it is on the south wall, rather than the more normal north wall.

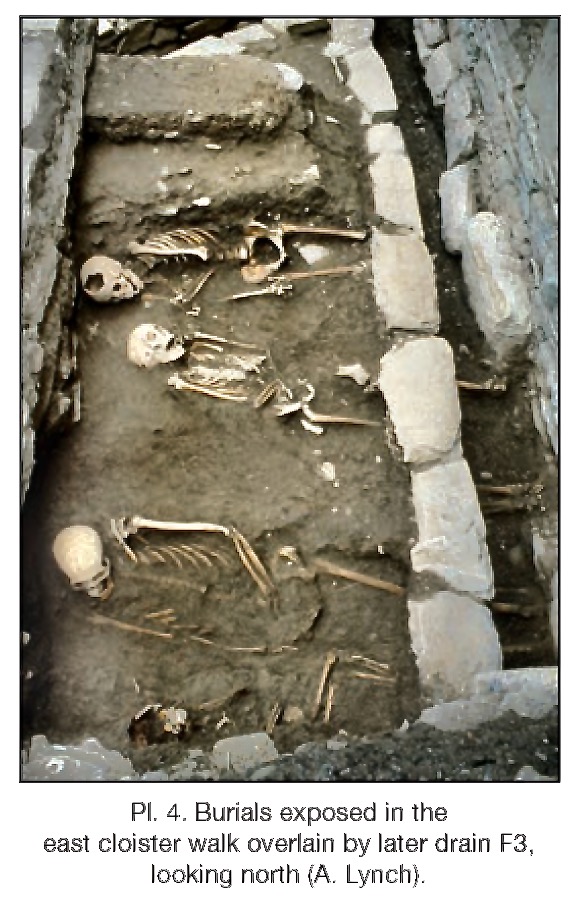

The cloister was filled with rubble when Ann Lynch started her excavations. Nothing of it was to be seen, but as you can see the excavation revealed a small but perfectly formed feature.

And it seems that this is where the monks were buried! As the friars were pacing the cloister walk, intoning their office, they were walking on ground above the bones of their brethren who had died before them. Twenty four of them were found, aligned with their heads to the west and their feet to the east. There were no grave goods: they were buried as simply as they had lived.

Later, in the 17th and eighteenth centuries, the west end of the friary was used as a fish palace – a place for curing fish and packing them into barrels. The holes in the walls in the image below would have held press-beams. See Robert’s post Fish Palaces and How They Worked, for more on this. Somehow that seems like an ignominious end for a place built as a focus of worship.

Today, the first thing you see as you step off the ferry is the friary, peaceful and beautiful in its island setting. It has seen its fair share of turbulence, of industry and of neglect. Now it reminds us that life goes on despite all that, but it never stays the same.