We have a major new player in the arts scene in West Cork. Over the last couple of years, Cnoc Buí (cnoc buí – yellow hill) Arts Centre in Union Hall, has quietly established itself as a significant focus for the arts. I have attended several exhibitions there, always marvelling at the space, the light, the curation and the excellence of the art on exhibit. Here’s the list for 2024, although it doesn’t include the current exhibition, and that’s the one I want to write about today.

First of all, a little about Cnoc Buí itself (photo above by Amanda Clarke). As the name suggests, it’s a yellow house, beside the sea in in Union Hall, renovated and fitted out for the arts. It’s the brainchild of Paul and Aileen Finucane, who have come to live in Union Hall permanently, after owning a house here for forty years. Passionate about art, and avid collectors, they are ‘giving back’ in the most magnificent way possible through their philanthropic efforts. Read more about them and Cnoc Buí in this story from the West Cork People. (Photo below courtesy of the West Cork People.)

Those of you not living in West Cork – you have no idea how rare it is to come face to face, in your own backyard, with the great Irish artists of the 20th century. Normally we have to go to Dublin, to the National Gallery, or the Hugh Lane.

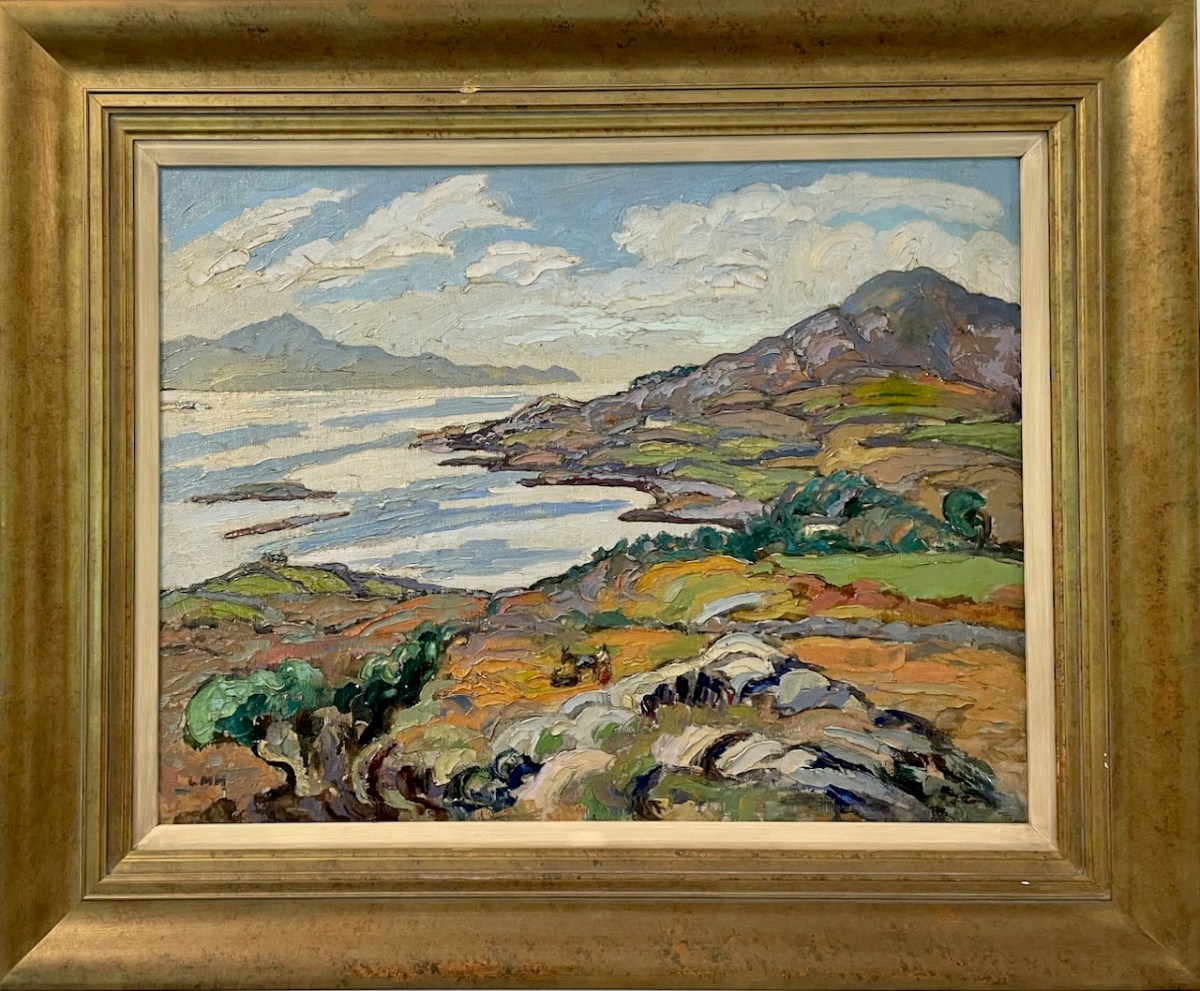

Ahakista by Letitia Hamilton

I often get my fix from the wonderful Facebook Page 20th Century Irish Art, and I have come, thanks to that source, to recognise many of the names and styles of our leading artists.

Phyllis Leopold’s The Belfast Blitz

The only other comparable experience I have had here in West Cork was with the Coming Home expedition in 2018. Don’t get me wrong – I love 21st century art and we have SO many excellent artists and great venues here in West Cork, and we have written about and reviewed many, many shows. Remember The Souvenir Shop? Rita Duffy is here as well.

Kathleen Fox, Still Life with Bust

This show emphasises Irish women artists – over half of the pieces are by women. We are all rediscovering the superb women artists who were in the shadow of famous husbands (Grace Henry, Margaret Clarke) or unjustly neglected (Kathleen Bridle, Hilda Roberts, Gladys Mccabe), better known as stained glass ‘craftswomen’ (Evie Hone, Sarah Purser, Olive Henry, Kathleen Fox), written off as mere ‘Illustrators’ (Norah McGuinness), or who were even actively discriminated against by the male establishment and dominating figures like Sean Keating. Some are getting the last laugh now – there’s a new exhibition opening now in the National Gallery devoted to Mildred Anne Butler, who is represented in this exhibition.

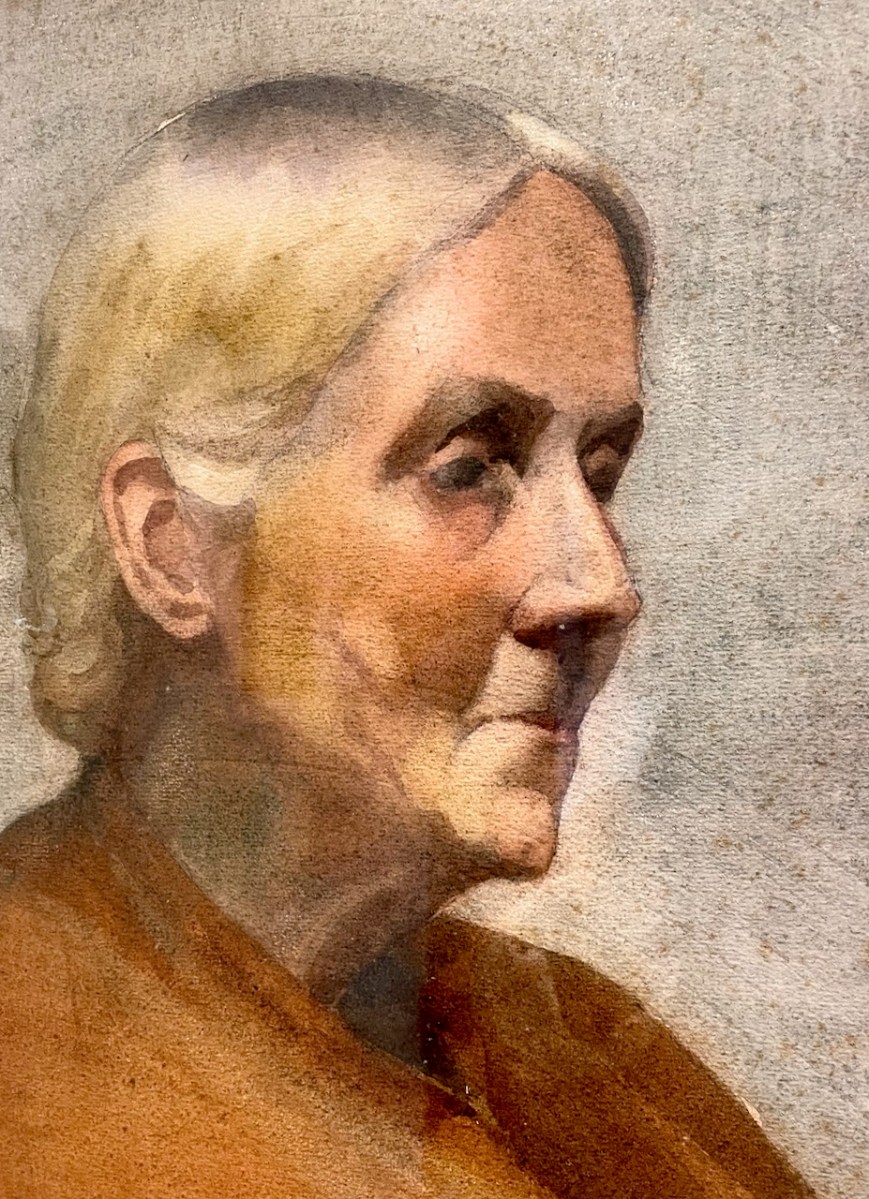

Olive Henry is more familiar to me as a stained glass artist, so I was delighted to see this fine portrait

But it was women who led the Irish art world into the modern era: The Irish Exhibition of Living Art was founded by women who had been able to afford to go abroad to study and had picked up newfangled ideas on the continent – women like Evie Hone and Mainie Jellett. Young artists flocked to their exhibitions, while the old guard stuck to their conservative, academic forms – echoed, of course, in the suppression of women and modernism in the new Irish State.

Evie Hone, Drying Nets – The Harbour Wall, Youghal

But here they all are, in Union Hall! The pioneering, courageous, persistent, driven, women of the new State.

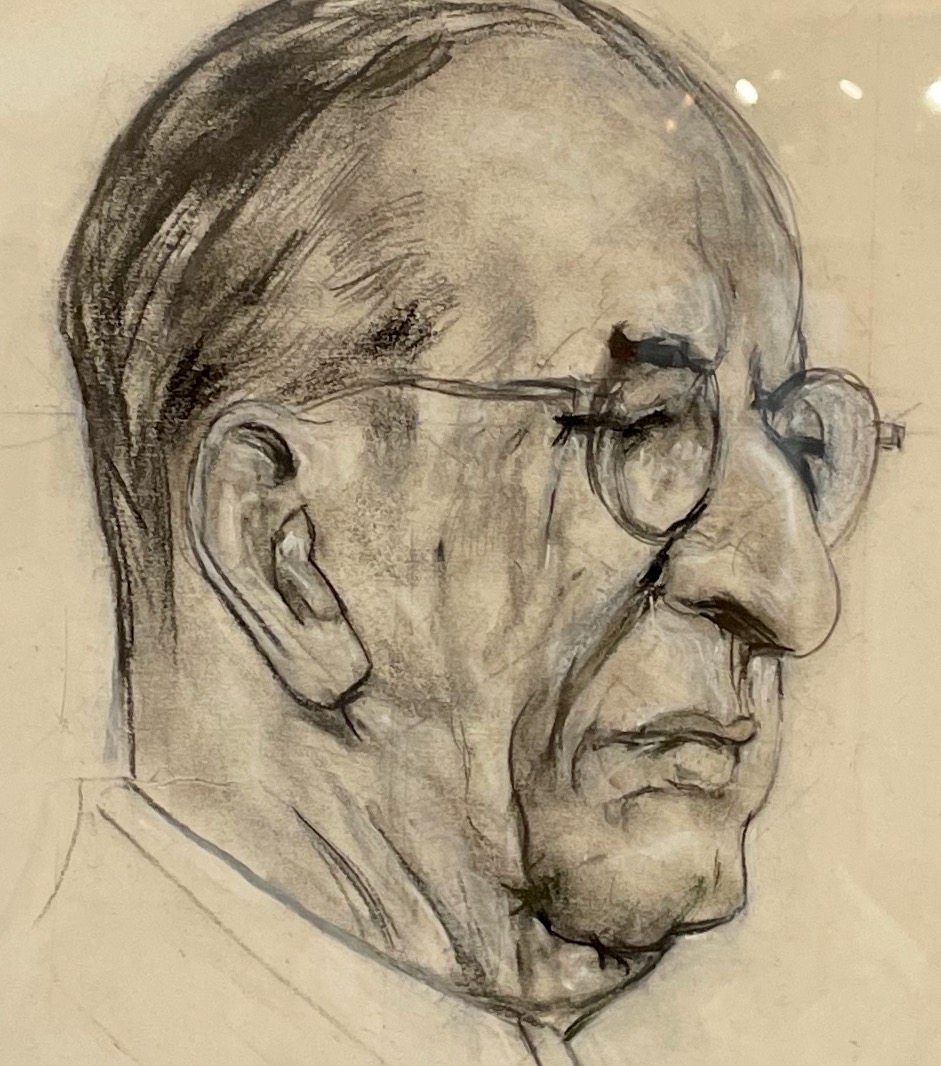

Portrait by Hilda Roberts

There are lots of men here too, of course – even Sean Keating, with a marvellous charcoal portrait of deValera. Did they grumble together about the goings-on over at the IELA?

John Sherlock was new to me and a great discovery – I have used his bust of John Hume as my lead image.

Oisín Kelly (above, Bust of a Young Girl) is a personal favourite, and I have mentioned Thomas Ryan in another context: he is also, perhaps, under-appreciated. George Campbell, despite designing windows for Abbey Studios in the 60s and 70s, never got written off as a stained glass craftsman. The portrait (below) is of his mother, Greta Bowen, who only began painting at 70 and exhibited well into her 90s.

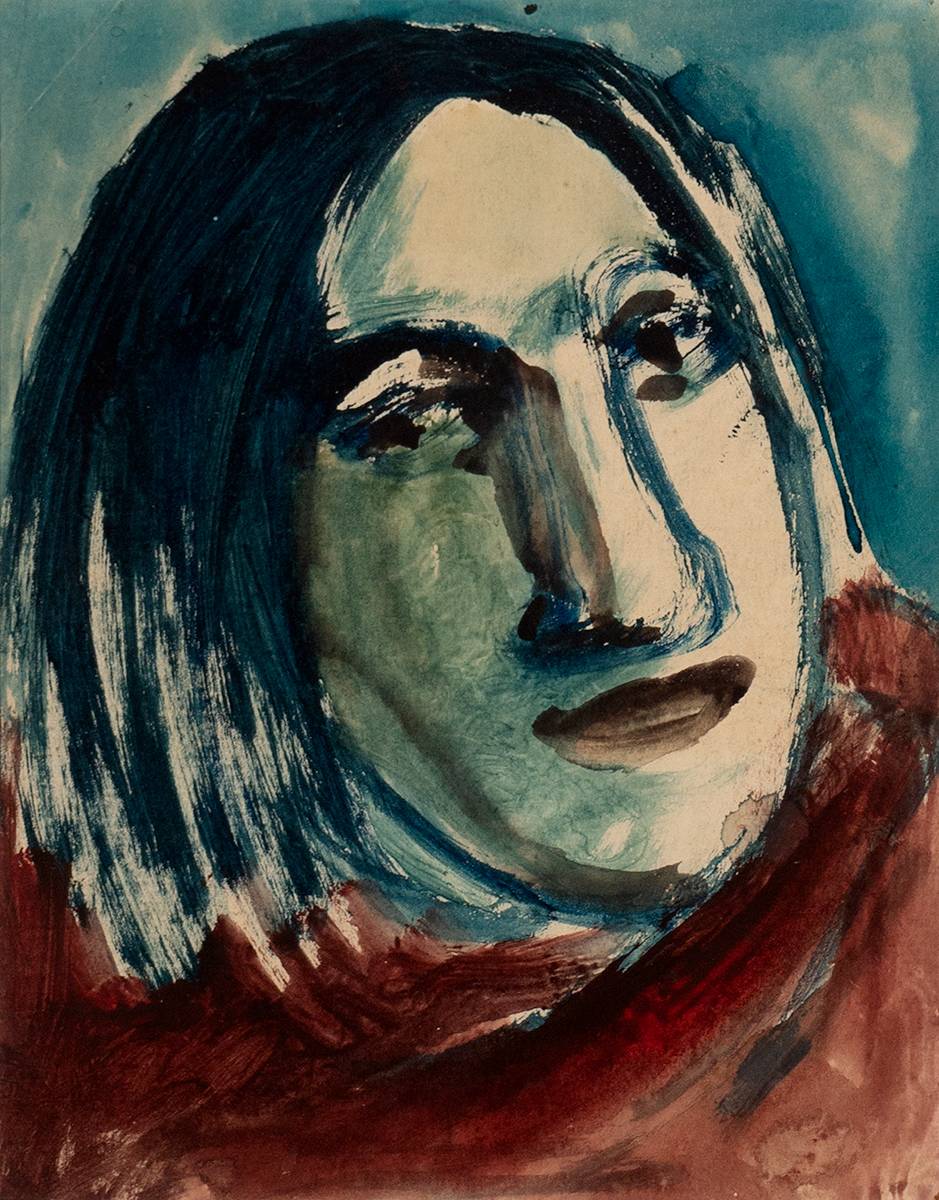

I recognised this painting, Mary Magdalen (below) as a Margaret Clarke right away, even though I had never seen it before.

It’s that combination of exact portraiture (I am willing to bet the angel was based on one of her children), the haunting expression in the eyes of Mary Magdalen, and the way the gestures mirror the scenery and shrubbery behind the figures.

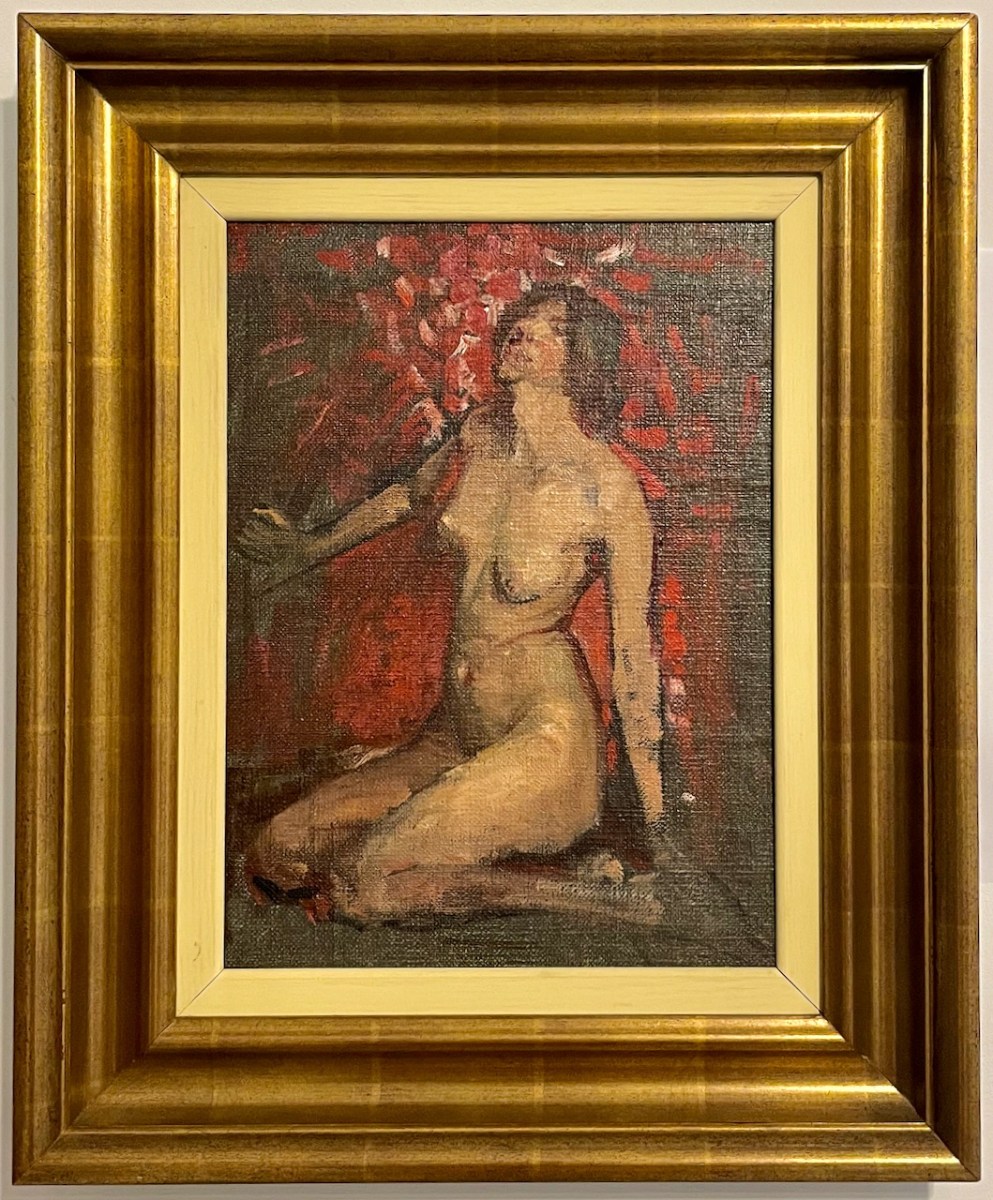

The Sarah Purser is interesting on a number of fronts. Purser made her name with portraiture, using her connections to obtain many commissions – she herself said she went through the British nobility ‘like the measles.’ But this nude (below) is of Kathleen Kearney, ‘Mother of All the Behans’, who worked for Purser as a young (and very beautiful) woman. Sarah Purser’s many talents (she was a superb manager of An Túr Gloine Stained Glass Studio among many other things) are currently on full display at the Hugh Lane Gallery.

I have only given you a flavour of what’s in this exhibition. If you can, get down to Union Hall and take a wander through it yourself. If you get there on a weekend, the charming Nolan’s Coffee House will be open.