It has become my habit over many years now to mark St Brigid’s Day with a post. This link will bring you to the last five. If you have read them, you will know already that the camp I am in is the one that sees her as an historical figure – an actual woman, powerful and pious, that ruled benevolently over Kildare in the 5th/6th centuries. I used, to the extent that I could, the original documents that lead us through her life – an account by Cogitosus written in the year 650, and the Vita Prima, written 100 years later. Both are likely to have been based on an earlier Life by St Ultan. Since both accounts are mostly a list of miraculous happenings, I do not hold them out as factual – what is convincing is that they were written so soon after her death and that they are so specific about the establishment of her foundation in Kildare.

Over the centuries much folklore and mythology has accrued to St Brigid’s story, as it does inevitably to all of these Irish Early Medieval icons. Most of it has enriched her legendary image. However, I do find it puzzling that so many people are now convinced that she never existed and is simply a Christianised version of a mythical ‘Celtic’ goddess. Funny, we don’t do that to our other founding saints, Patrick and Columcille.

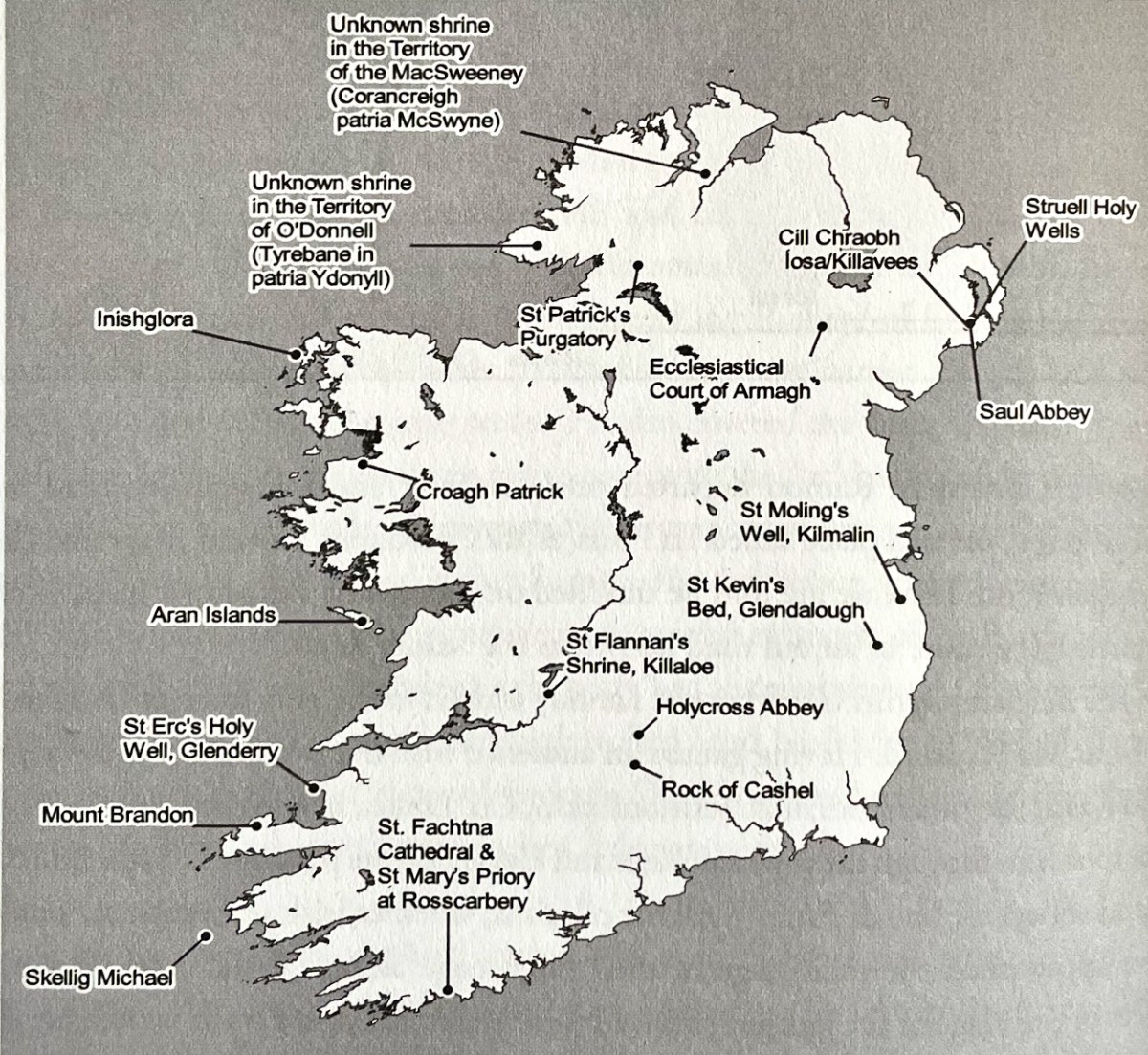

I usually go for stained glass images but this year it will be about her holy wells. This is partly in homage to Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry – or in other words to my good friend Amanda Clarke, with whom Robert and I, and now I, have had so many adventures, out Good Well Hunting.

I was privileged to be on the first ever outing – to St Brigid’s well in Lough Hyne on St Brigid’s Day in 2016 – exactly ten years ago (above). Amanda is marking this auspicious anniversary with a special post summarising those ten years and what she has learned along the way. Do pop over and have a read – since her book is now out of print, it may be the closest you get to a summary of her wisdom. Lough Hyne is a small, obscure well, hard to get to but as full of intriguing detail and structures and folklore as any of the more frequented wells. On the other end of the spectrum are Brigid’s large and most well-known wells. We have been to several of both types. I’ll start with three of the most-visited.

Nothing can quite prepare you for the impact of Brigid’s Well in Liscannor, Co Clare. At first it seems like a well-tended garden-like area with the obligatory statue, but then you see the entrance to what looks like a cave.

And that’s kinda what it is – a womb-like space filled with statues, icons, candles, supplications, photographs. It is a powerful testament to what a living tradition this is – to visit a place associated with her, to pay your devotion and ask for her intercession.

Kildare, of course, is the city and county most associated with Brigid and St Brigid’s well outside Kildare town is a beautiful and contemplative place. It is laid out in such a way to lead you through the pattern of prayers, and it encourages you to slow down and feel the atmosphere.

Another such is the Brigid’s well near Lough Owel near Mullingar. This one features a statue showing her in the act of casting her brat, or shawl, across the land to claim it for her monastery.

There’s a space for a priest to say Mass, the Stations of the Cross, and the well itself, topped by a green mound and a St Brigid’s Cross (my feature photograph for today)

But it’s the hidden wells, down almost-forgotten paths, that resonate with me most. Amanda, with her exhaustive research, has led us to several. This one is near Carrigillihy in West Cork. Only the locals really know about it – there is no signpost and you have to look out for a tiny path off the road.

My lead photograph is the well itself. From it, there is a view to Rabbit Island, where the well was originally located. Realising that it was now too inaccessible, the well re-located itself (they do that) to the mainland.

Sometimes it takes real effort to get to a well – thus it was with Stonehall, in Co Limerick. The map was vague, and directions even vaguer but there was nothing vague about the mud.

Once you finally get there – across this field and up this rutted path – and catch a glimpse of something promising (Amanda swears by small gates), the sense of achievement is huge.

You might be the only people who have been year in years, but here it still is.

One of my favourites is the one at Britway, not too far from Rathcormack in Co Cork. We discovered this one on our own, in the course of an expedition, and I loved the vernacular nature of it but especially the statue. Brigid had been furnished with a coat-hanger crozier, and her eyes had been coloured black, giving her a threatening air. I believe she may have been refurbished more recently, so perhaps is not quite so scary now.

I leave you with some images of Amanda in her happy place.

Congratulations, my friend, on ten amazing years of exploration and discovery and on becoming the Go To Authority on the Holy Wells of the south west of Ireland.