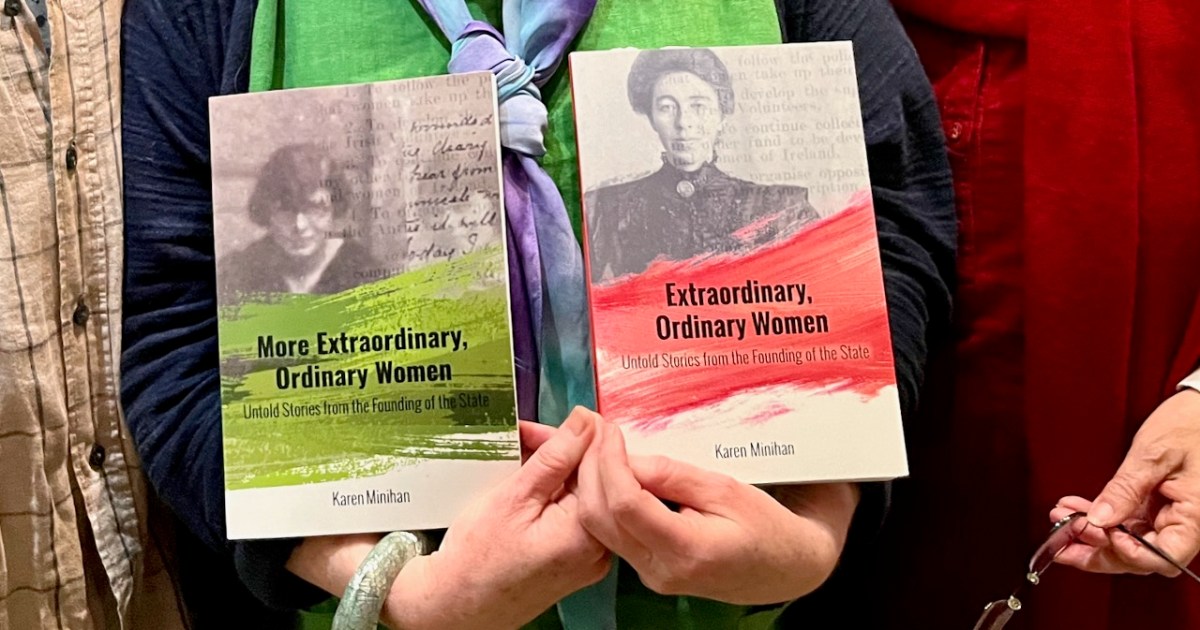

We launched Karen Minihan’s new book, More Extraordinary Ordinary Women, on St Brigid’s Day. The date was apt – Brigid was a woman venerated in her time, who founded the ecclesiastical city of Kildare and ruled benevolently over a vast monastic empire, but still lost out as Patron Saint of Ireland to a man. However, we now have a brand new public holiday in her honour and I think all the women in this book would be pleased about that.

Here are May and Tess Buckley from Gortbreac in Castlehaven, who get a chapter each in this book, with their brother. They showed remarkable courage and resourcefulness – they also happen to be directly related to Ellen Buckley, O’Donovan Rossa’s second wife.

This is a follow-up to Karen’s first book, Extraordinary, Ordinarily Women, and I can’t emphasise enough the importance of the work that she has done with these two books. She has brought the lives of strong courageous women out of the shadows, and challenged the prevailing narrative that elevated the role of the male volunteers and members of the IRA over the parts played by everyone else. It’s not an exaggeration to say that women’s stories were more than neglected but that they were actively suppressed.

Tess Buckley’s telescope – she used it to identify any approaching military or police movements from afar

When the Military Service Pensions were established in 1924, women were explicitly excluded. Ten years later they were included in Military Service Pension Act 1934, which established five grades of service – A B C D and E, but relegated women to grades D or E. To get a D pension you had to be a Member of the headquarters staff or executive of Cumann na mBan OR in command of one hundred members or more. To get an E pension you had to prove you were in active service. They didn’t make it easy – requests for more information, for verification and letters of support – it often got so wearying that the women stopped pushing or said simply they had nothing more to add.

This is Mary Anne O’Sullivan of Bere Island on her wedding day. The situation on Bere Island was very difficult due to the presence of a British Army Camp (there until 1937) and Mary Anne showed great courage and presence of mind in hiding an escaped IRA prisoner

Many of them never spoke about their experiences, which made Karen’s research all the more daunting. This generation is only now discovering what their grandmothers and great-aunts did, sometimes by perusing the Pension files, or by discovering old documents in attics. Four of the stories in this book involve sisters – in Molly Walsh’s story Karen notes:

Molly did not speak of her experiences during this time to the generations that followed, she only spoke to her own siblings, sometimes they would go into a separate room to talk.

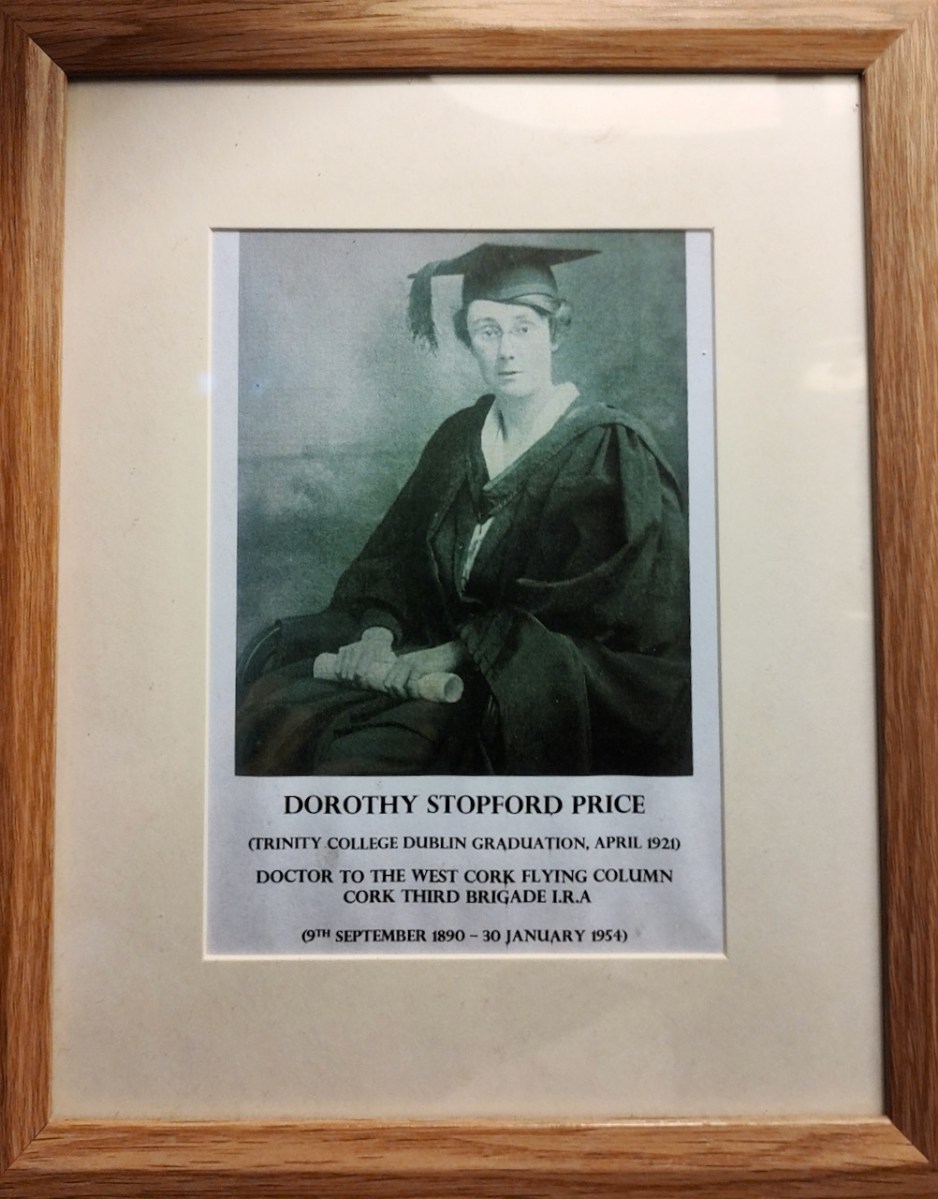

One of Molly’s great friends was Dorothy Stopford Price (above), who came from a landed Protestant family but spent time in Kilbritain teaching first aid at first and then as the community doctor and as medical officer to the local IRA Brigade. As an aside, although Dorothy pioneered the treatment and vaccination for TB in Ireland (below), all you ever hear about is the role played by a man, Noel Brown.

You have to read the book yourself to see how daring, brave and well-organised these women were, but I do want to tell you something of the story of Kathleen O’Connell of Ballydehob, who lived in a house two doors down from Working Artists’ Studio where we launched the book. She was an incredible woman – here are just some of her accomplishments, taken from Karen’s book.

In the Nominal Rolls of Cumann na mBan she is recorded as Captain of the Ballydehob branch and, by 1921, she was the Treasurer of Schull District Council (including Ballydehob), which had 114 members. What is also apparent is that she was trusted with possessing and delivering the secret, important information that the dispatches contained. And, of course, it meant that she put her own safety at risk. There is also a record of Kathleen being involved in setting up four or five “hospitals” in her area.

There was raid after raid.

During a Black and Tan raid on the town which occurred immediately after the vols. had been here (the house was reported) I had a large quantity of ammunition got by the volunteers in some raids on ex-policemen’s houses and elsewhere which was left to me to dump but I hadn’t got time…I got it out of the house by putting it in a large hand-basket and covering it with cabbage & bread. I went more or less in disguise wearing a shawl & long skirt, to get out of town to the dump, or safety somewhere, I had to ask the sentry for permission to get through…

The village of Ballydehob was surrounded. She was sent by the sentry to the officer in charge and she managed to convince him to let her through …as I said I wanted to take bread home to children; all this time I had the basket of ammunition and some literature. I went about a mile with it. She had two loaded revolvers, a holster and some clips of bullets; and the consequences of being caught were stark: They would have shot me probably if they had discovered it.

I took part in an ambush which was laid at Barry’s Mill. Took out food a couple of times during the day alone, in Wood’s commandeered horse & trap, also took dispatches which arrived while they were there.

She also scouted for the Volunteers that day, travelling back and forth to the mill.

On the last trip I went out there, alarm was given of the approach of the enemy. I could not then get back. Commandant Lehane gave me his 45 revolver and I remained their with the others for a considerable time, until it was reported the military had gone some other way. . .

17 lorries and private car with a ‘lady searcher’ arrived around this time in Ballydehob in order to search her and her home. She had been anticipating the visit – “I had everything dumped but the dispatch. It was in my pocket. I ate it.”

This is the house – the colourful one on the right in this picture – in which Kathleen O’Connell lived in Ballydehob

Kathleen was ruined financially by all her support for the cause. Letters of support for her pension application were fulsome in praise of her work and her commitment. She was awarded a grade E pension in 1939. She died, here in 1945, aged 50. She had not married and had no children, and all memory of her gradually disappeared from Ballydehob. When Karen went looking for the house she had lived in, it seemed nobody could remember the heroic Kathleen O’Connell who had once lived here.

Another view of the house in Ballydehob, from Google Maps. There should be a plaque!

However dangerous Cumman na mBan activities were during the War of Independence, those dangers tripled during the Civil war, as did the horrors of families ripped apart. Cumman na mBan took an anti-treaty stance, and where they now supported all the efforts of the anti-treaty side, the pro-treaty fighters knew all their secrets, their hiding places and their habits. They had to be, therefore triply ingenious – and they were!

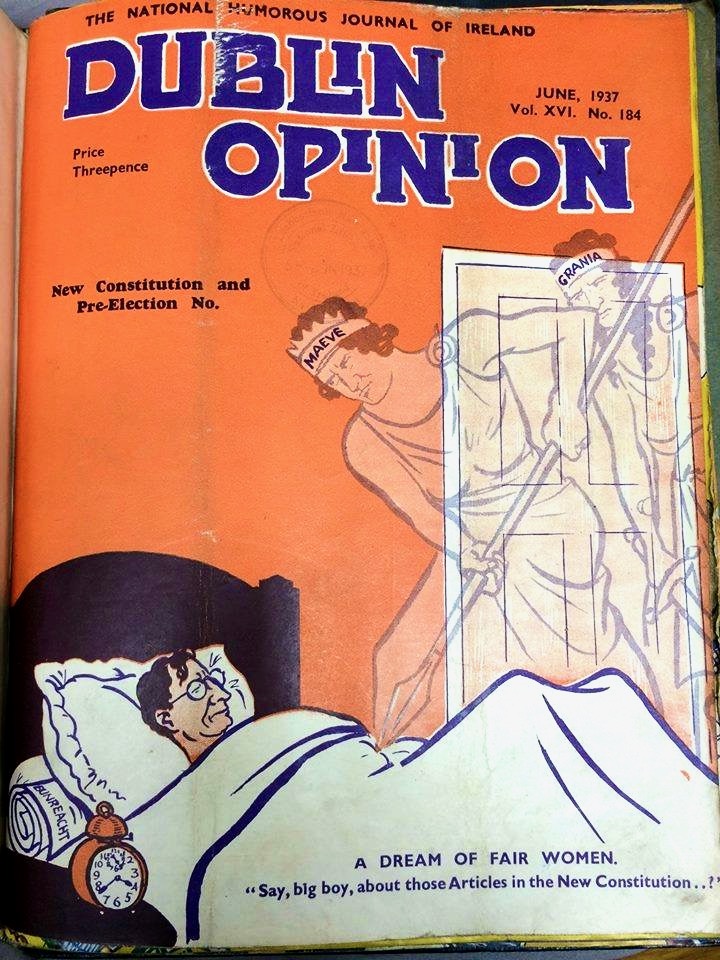

Another reason why now was an apt time to Karen to release this book is that we are facing an upcoming referendum. In the 1937 Constitution, heavily influenced by the Catholic Church – Archbishop McQuaid (above with deValera) submitted multiple comments and suggestions for amendments – DeValera and his government included this provision:

ARTICLE 41:2: In particular, the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.

This felt like a deep betrayal to many women of Ireland, who had rallied to the cause taking as their inspiration the words of the 1916 Proclamation, which said: The Republic guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens, and declares its resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and of all its parts, cherishing all the children of the nation equally.

The cover of Dublin Opinion in June 1937. Queen Maeve and Grainne Mhaol are poking the sleeping deValera, who has the Constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, under his pillow

The upcoming referendum asks us to vote to remove the wording of Article 41:2. It’s 2024 – 100 years since these extraordinary ordinary women were playing their part in the founding of the state, only to be banished to a life within the home.

I like to think that Kathleen O’Connell, Lizzie Murphy, Tess and May Buckley, Molly Walsh and Dorothy Stopford Price, and all the other Extraordinary Women, are up there in heaven, chatting to one another over pots of tea, and casting a protective eye over the campaign to remove article 41. When it’s voted out, I see them nodding their heads and saying at least all our work wasn’t in vain.

I was honoured to be asked to launch the book!

Let’s all get out and vote for this constitutional amendment! It’s the best way we can honour the work that these extraordinary women did. That – and buy Karen’s book! It’s available in bookstores in West Cork or by contacting the author.