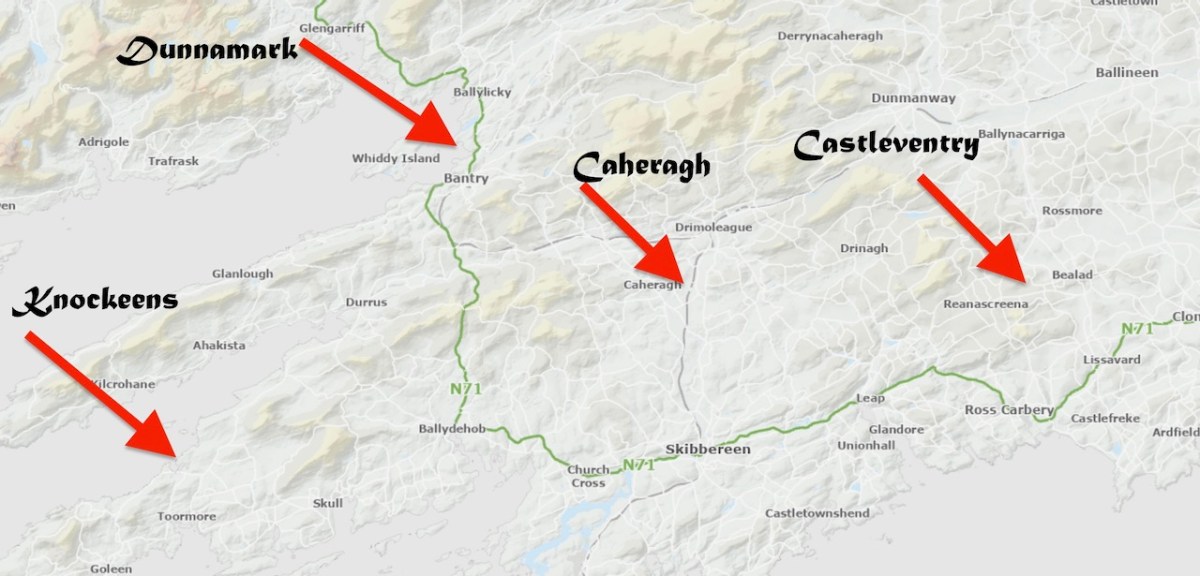

Last week we set out to figure why the Anglo-Normans are curiously absent from the archaeology of West Cork. I told you about our exploration of Castleventry, and how Con Manning immediately suspected this was not your average ringfort, and of course, eventually proclaimed it to be an Anglo-Norman ringwork. I am leading again with an AI-generated image – I am having fun playing around with DALL·E but am under no illusions about its historical accuracy!

Our next site was courtesy of David Myler, author of the new Walking with Stones. He took us to see an intriguing site at Dunnamark, just outside Bantry. In his book, David also highlights the local convention that this is a Dane’s Fort – a common designation for all kinds of constructions around Ireland.

This was another of the sites identified by Dermot Twohig as an Anglo-Norman ringwork. In fact, Dermot said Dunamark is one of the best examples of a ring-work I have seen in either Britain or Ireland. Con concurred. In his book, David also highlights the local convention that this is a Dane’s Fort – a common designation for all kinds of constructions around Ireland.

This is another massive fortification, with very deep ditches and a high ‘platform’ as the interior of the fort.

In the National Monuments record it is labelled a ‘cliff-edge fort and is described thus:

Description: In tillage, on cliff edge, on E shore Bantry Bay. Roughly D-shaped area enclosed by earthen bank S->NNE, with external fosse; slightly convex cliff edge NNE->S. Possible souterrain (CO118-004002-) in interior.

In his article in Archaeology Ireland, Con points out that

Dunnamark was a particularly important castle, having been one of two demesne manors of the Carews in West Cork, and the caput of the cantred of of Foniertheragh.

He also says that a low-level bit of a masonry set into the central mound and parallel with the entrance causeway might be part of the counter balance slots of a drawbridge. Here’s what Con was looking at – it takes a medieval archaeology specialist to recognise such an unpromising set of stones.

Another interesting feature of this site is the narrow channel riught beside the bank, which would have allowed small boats to come right up to the fort.

Our third site may be familiar with regular readers – it’s the site I described as the original Dunmanus Castle in my post Dunmanus Castle – the Cliff-Edge Fort. Go back and read that now and then come back here.

You will see that I was puzzled by it when I saw it and I was really pleased when Con confirmed on a subsequent visit that this could indeed be another Anglo-Norman ringwork.

Interestingly, since I wrote that post I wrote about the Bath Map of Cork, which shows an actual castle – as complete as Dunmanus Castle, on the site!

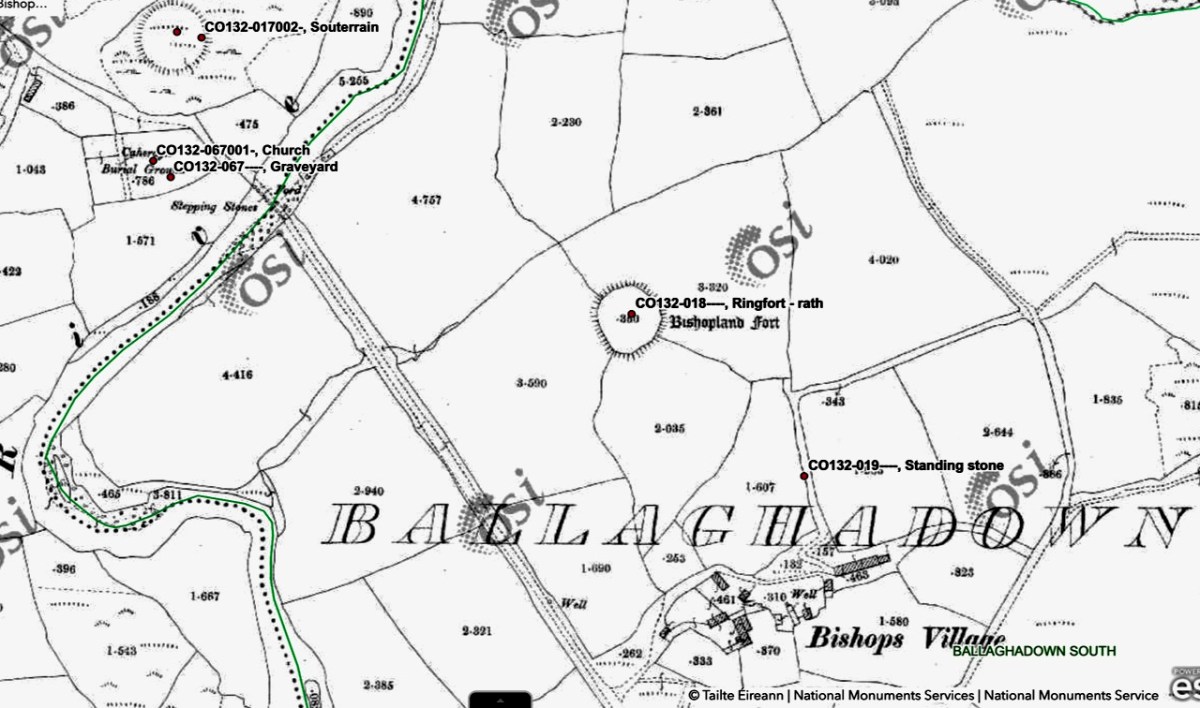

Our final site is at Caheragh, and this one is bit more speculative. A high knoll towers above the ruined church and its surrounding graveyard and on top of that hill is what has been labelled a ringfort. However, once again, it doesn’t quite feel right as a ringfort.

It has panoramic views across the surrounding countryside and sits on the middle of a medieval landscape that includes many ringforts, and an area known as Bishopsland, and the winding Ilen river.

The fort on top has obvious remains of buildings, one of which may be what is left of a small tower.

The knoll, although natural, looks like a motte – why build one if you don’t have to? From the top you can see all the way over to Caheragh village.

For me, the defining characteristics of these ringworks so far has been very much in accordance with what Grace Dennis-Toone laid out in her thesis – strong fortifications, situated strategically either with panoramic views or maritime location. But we know ringforts that are like that too. The extra factor for me is that they also seem like truncated mottes – raised platforms that fall short of the height needed for a motte, but still enough to dominate the landscape. Castleventry and Caheragh take advantage of natural elevations, while Knockeens and Dunnamark have constructed raised platforms within deep ditches. It may also have been that Knockeens was originally circular rather than D-shaped – see how much erosion has taken place there (below).

So – readers, do you have any other examples you suspect might fit the bill for an Anglo-Norman ringwork? It would help if it has some documentary evidence so get busy researching medieval manuscripts. No bother to you! I have already heard from one knowledgeable local, and hope to have another field soon trip in his area. We know they were here – between us, maybe we can re-write the text books for West Cork.