Our last, and most magnificent, cashel in this series is Staigue. Majestic, imposing and mysterious, it sits at the head of a long valley with views down to the sea, almost 4kms away.

Staigue is the one that has never been excavated, and so it is the one that we can project our own speculations on regarding its age, its function, and its association with the fairies.

The thing that distinguishes Staigue from the other Cashels in Kerry I have written about so far is its sheer size. It’s what provokes awe. The first to write about it, in 1821, was the then-landowner F C Bland, who said:

When the appearance of the country, which is barren and uninviting, is considered, it must create surprise, what could have been the inducement to erect such a structure in such a place; and, when the traveller, whose curiosity has supported him through a long journey, the latter part of which for ten or twelve miles has been through a wild, uncultivated, though not an uninteresting country, first approaches it, he experiences a sensation of disappointment. For it stands a single object on a hill, and from its figure (being round) producing but little effect of light and shade; and, having no familiar object by which to measure its magnitude, and its importance being rather diminished by the extent and desolation of the surrounding scenery, he attaches a meaner opinion to it than it deserves. But when he enters it, he is struck with astonishment; and his imagination almost instantly transports him to distant ages lost in remote antiquity. He vainly endeavours to figure, in his “mind’s eye,” the beings who erected it, their manners, habits, and costume; until, “lost and bewildered in the fruitless search,” his mind returns to sober investigation, again to lapse into conjecture. This effect is not lost by familiarity:—I have visited it a hundred times, and have always experienced the same sensation.

Description of a remarkable Building, on the north side of Kenmare river commonly called Staigue Fort. Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Vol XIV, Dublin, 1825

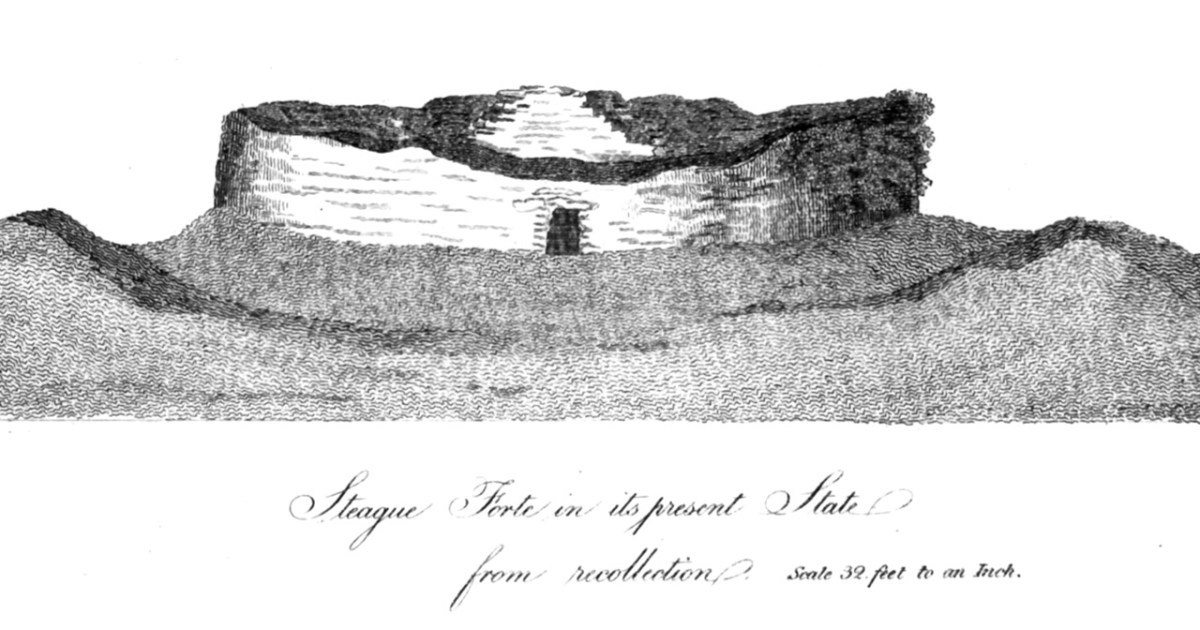

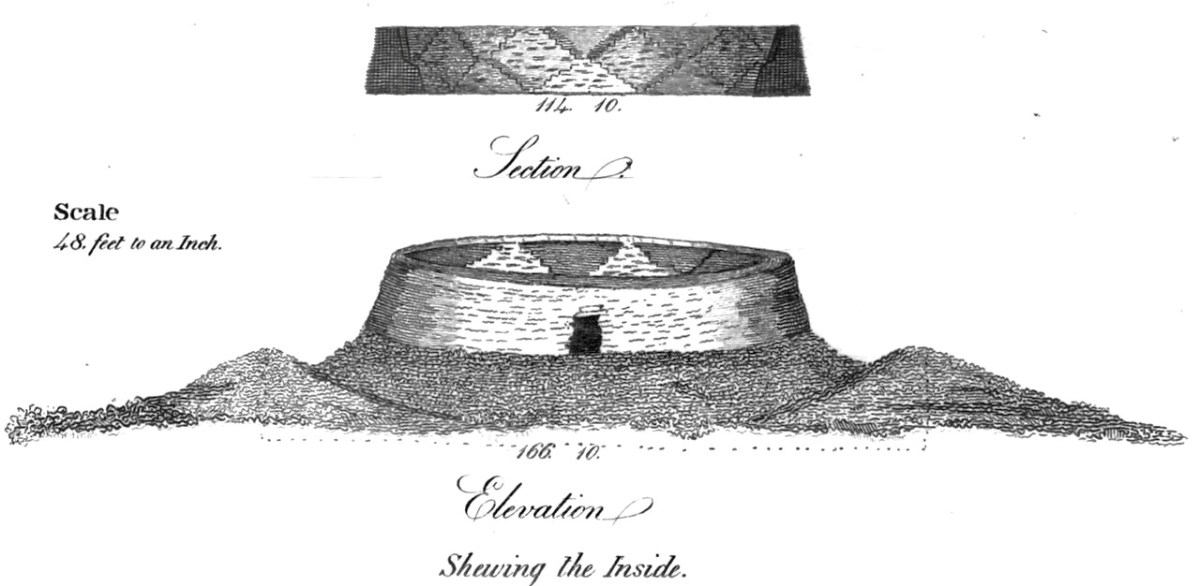

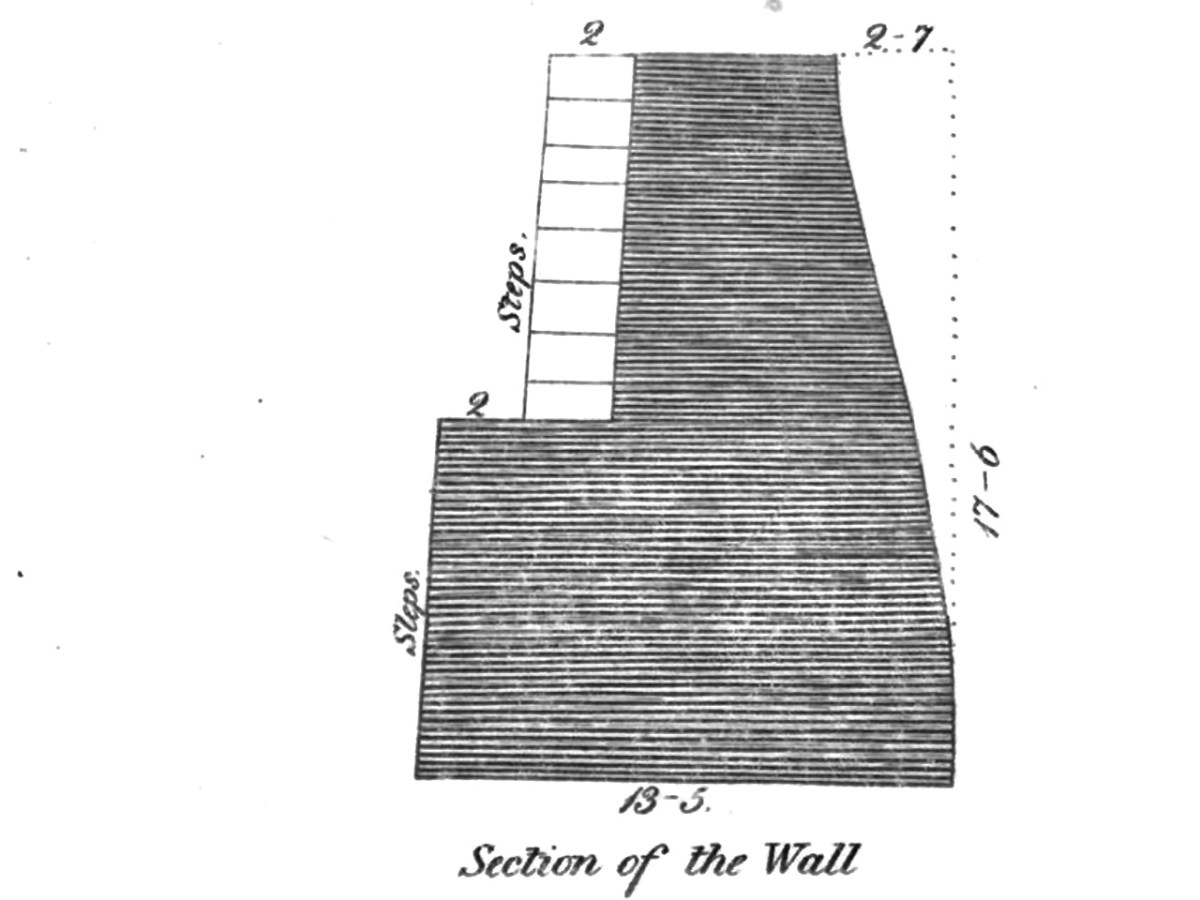

I know how he felt. Bland did a series of measurements and drawings of the fort, and they provide a charming antiquarian look at how it was 200 years ago, when it had been in use as a cattle pound. That’s one of his drawing at the head of this post. Here’s another.

But his account is more than charming – it provides an indication of how the fort looked at that time (even though the drawings are not exactly accurate). This is important because we need to know what interventions have been made over the years to the fort – interventions that can significantly altar the profile and appearance of the fort, as we have seen in the other three. For example, he referred to an ‘eve stone’ a term that is unfamiliar to me, and said:

In one part, where the wall is perfect, it is surmounted by a projecting eve stone, which, when complete, must have added greatly to the effect of the whole. This is indeed the only attempt at ornament in the entire building.

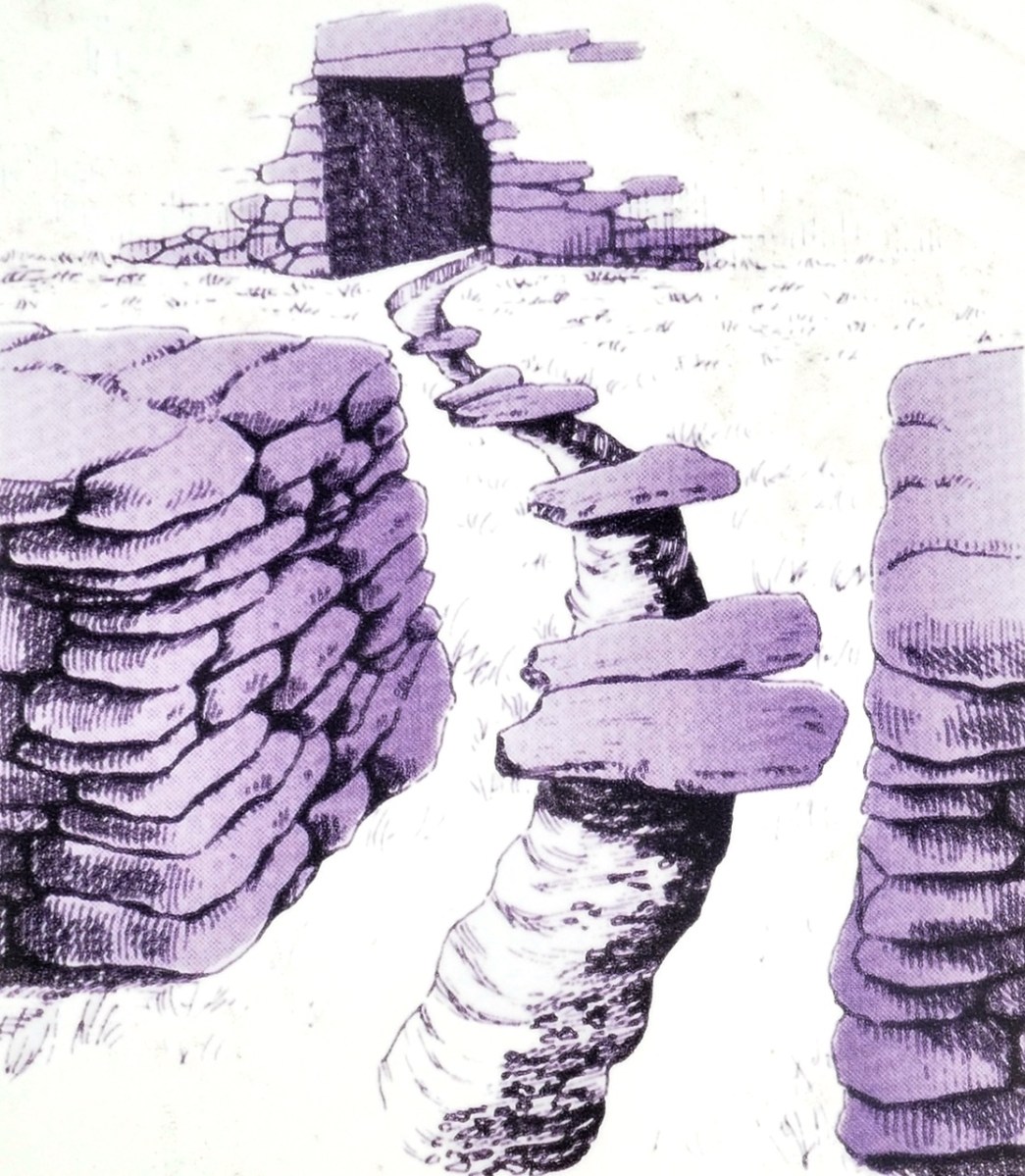

His own drawing do not show any special feature and whatever it was, no really obvious eve stone has survived the two centuries since he wrote this account. However, the National Monuments record does state The rampart stands to a maximum external height of 5.7m at N, where both Bland and Dunraven noted a number of coping stones projecting slightly over its inner wall-face (1825, 18-19; 1875, 24). Two of these remain in situ, and average 1m x .4m x .08m thick. Perhaps I need to go back and take a closer look.

The good news is that, of all the cashels we have examined so far in this series, Staigue seems to have remained most true to its original state. That is not to say it is identical to how it was 200 years ago – it has been tidied and stabilised, although when and by whom remains uncertain. There is a suggestion that Bland himself employed local workmen to do some restoration work, and another that the OPW did some in the 19th century.

While no records of these works remain, overall, the fort looks similar now to the older images we have of it. Historic edifices like Staigue cannot be left to crumble if significant numbers of people are visiting it. Sooner or later, as people climb on the walls, knocking off stones, it will deteriorate, creating a safety hazard and a dangerous situation for the monument itself.

The trick is to intervene as sensitively as possible while still providing safe access and I would say that this has been done well at Staigue, although readers may want to weigh on on this question. The photos above and below are from the Irish Tourist Board collection (used in compliance with their Creative Commons License) – they amply demonstrate that climbing on the walls was as irresistible in 1964 as it is now. The ditch around the fort is also quite obvious in the aerial photo.

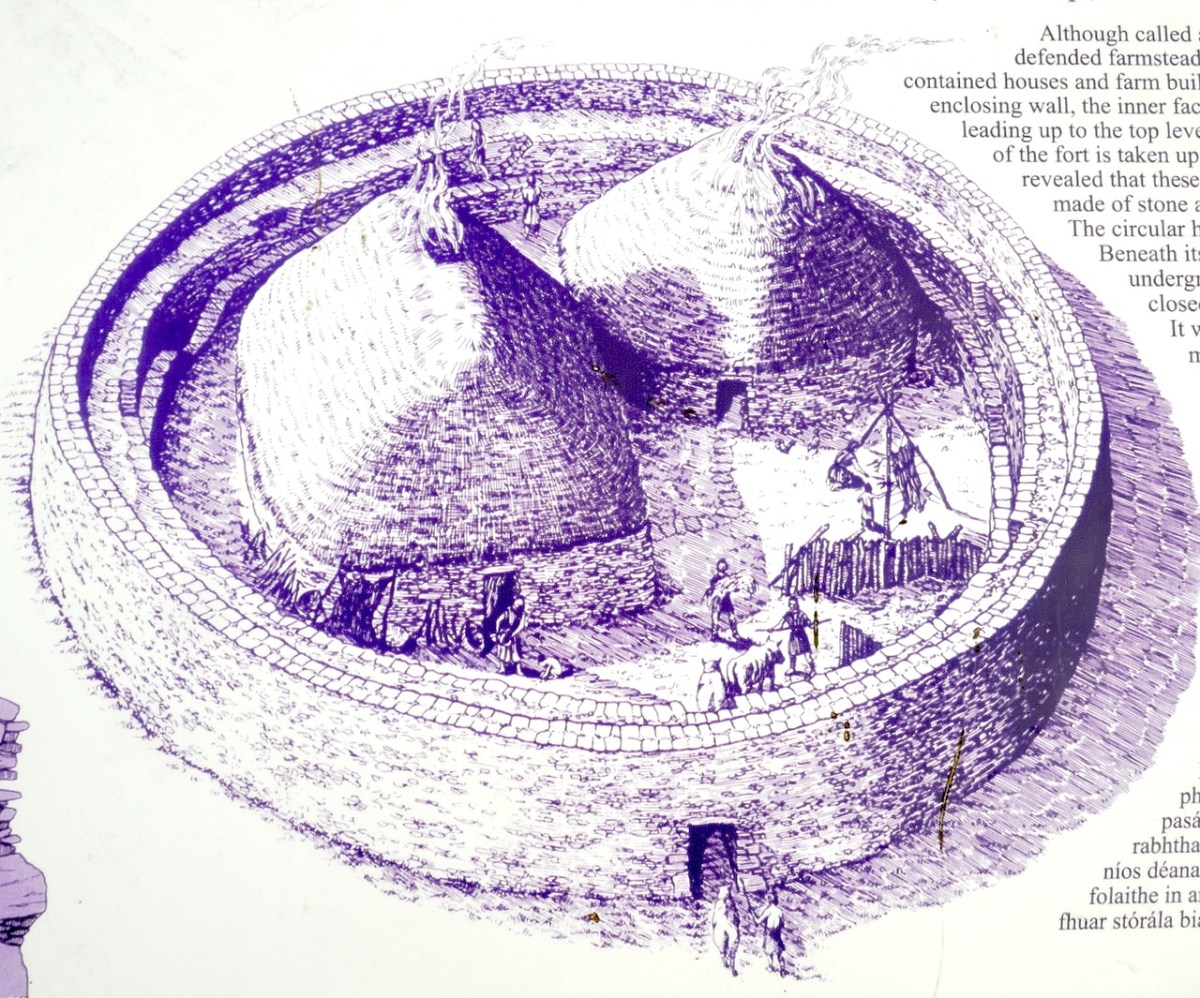

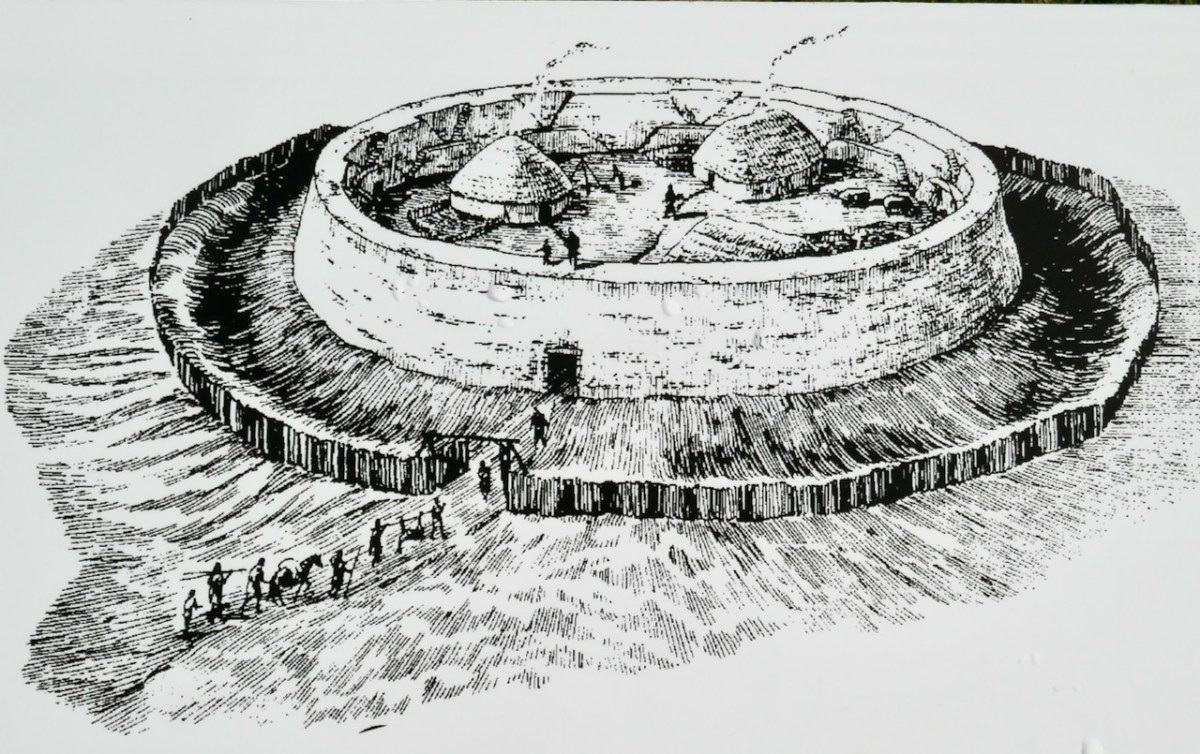

In essence, Staigue is similar to the other Cashels, with massive walls, two internal rooms or ‘cells’ in the walls, an entrance through the walls on the south side, and sets of stairs giving access to the top of the walls.

The stairs – the Irish word staighre (pronounced sty-rah) may have given the cashel its name – are the most striking feature. Commonly referred to a X-pattern, the first set lead up to a flat ‘landing’ from where the next set take off in both directions. You can see this really well in this 3D model of Staigue done by The Discovery Program. The image below is a still from the model – click here to go to it – it’s fun to manipulate it for yourself.

The entrance, surmounted by not one but two massive lintels, leads through the south wall, with a slightly inclined profile. The walls is lowest at this point.

The two mural chambers are to the left of the entrance and opposite it. Their use is unclear, but they may have functioned, like souterrains, as cold storage for food.

We do not know what buildings may have been inside the fort, although, as we saw in the other three, it was common for these cashels to have houses, whether for dwelling or for ceremonial use (as at Cahergal) or both. It is highly likely that any future excavation of Staigue would reveal similar constructions. The OPW sign (extract below) makes that assumption and says The fort was the home of the chieftain’s family, guards and servants, and would have been full of houses, out-buildings, and possibly tents or other temporary structures.

You remember our old friend General Vallancey from Beranger’s West Cork? In that post I told you that he was an antiquarian of the fanciful sort – forever banging on about druids and Chaldeans and coming up with far-fetched theories. In fact he pronounced Staigue to be a Phoenician amphitheatre! Perhaps Bland’s romantic illustration, below, put him in mind of such an interpretation.

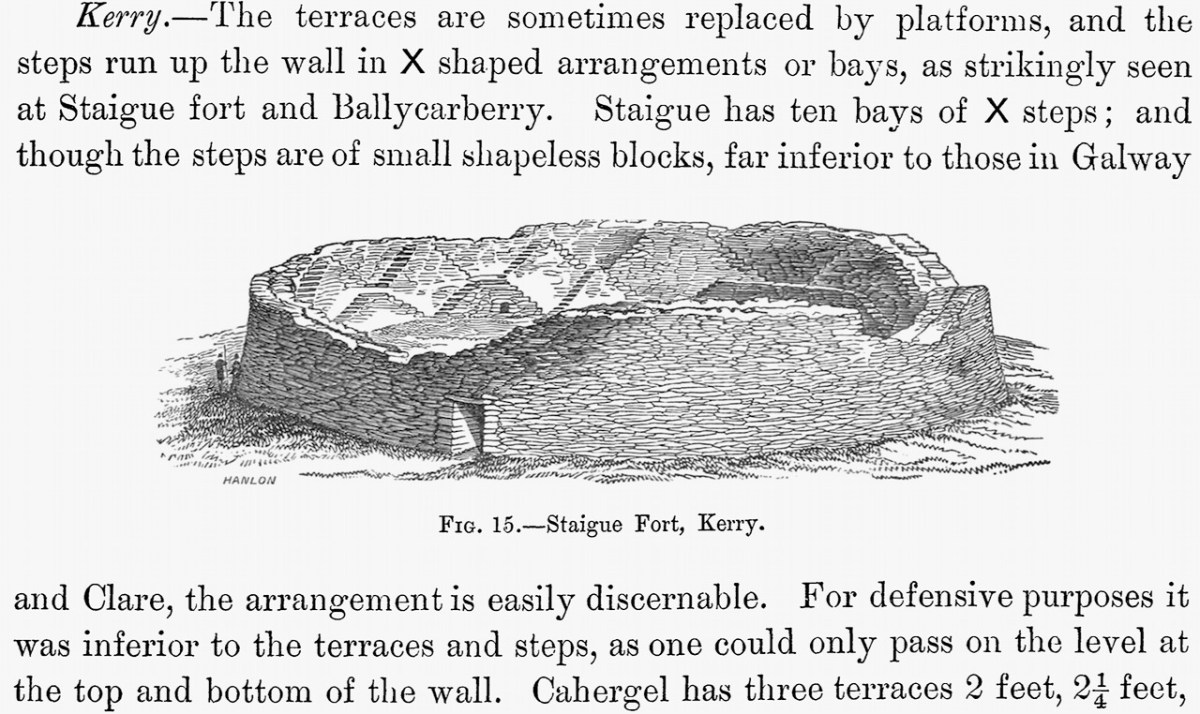

Westropp, one of whose main activities was bringing common sense to antiquarian discourse, in a series on forts written between 1896 and 1901, situated Staigue very much in line with other stone forts on the Western seaboard. The photograph below is from that series. He acknowledges the defensive nature of the huge walls, but declined to use what he saw as the simplistic term “fortress”.

As for their use as cattle pens (as Bland had suggested), he says:

It was, however, not unusual to keep the cattle in the residential fort; we find this in legend, as in the case of the cattle of Iuchna the curly-haired, and in that story, so often quoted, of the three forts of Ventry. What is stronger evidence is that the ancient laws of Ireland made provision for seizing cattle kept in forts, and even for keeping them impounded therein on dark nights. That this extended to later times we have seen in the fort-names Cahernagree, Lisnagry, &c., and perhaps even in the “pounds” of Dartmoor and the local name for Staigue fort “Pounda-na-Staigue.”

The Ancient Forts of Ireland: Being a Contribution towards Our Knowledge of Their Types, Affinities, and Structural Features. (Plates LII. to LIX.). Author(s): Thomas Johnson Westropp Source: The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, 1896/1901, Vol. 31 (1896/1901)

Westropp saw these forts as having multiple uses, much as Con Manning did more recently – places of assembly, of ceremony, and, if a dwelling, that of a high status individual. Indeed the command of resources it would have taken to build Staigue is staggering. The fact that it was surrounded by an outside ditch (no longer very obvious) might also add to its indentification as defensive. The photo below is from a 1950 piece by Angus Graham (Some Illustrated Notes from Kerry, in

The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 81, No. 2 (1951), pp. 139-145)

We have seen that the three other Kerry Cashels have been dated to the Early Medieval and Medieval period: Leacanabuaile to the 9th and 10th centuries, Cahergal in use between the 7th and 9th centuries and again during the 11th and 14th, and Loher from 400 to 1600. It is puzzling therefore, that the OPW sign at the fort assigns a likely date of the early centuries AD before Christianity came to Ireland. In other words, the Iron Age. This assertion, of an Iron Age date, is repeated in various online sources about Staigue (including an even more vaguely worded reference to “during the Celtic Period.”). There is no evidence that Staigue was built significantly earlier than the other Kerry Cashels. In all likelihood, it belongs in the same medieval tradition of cashel-building.

If you get to Kerry, go visit all four of these remarkable testaments to our past. You will find yourself wondering at the context in which they were built, and the complex and highly stratified society in which resources could be marshalled to build something that would serve to remind all who saw it, who’s in charge here!