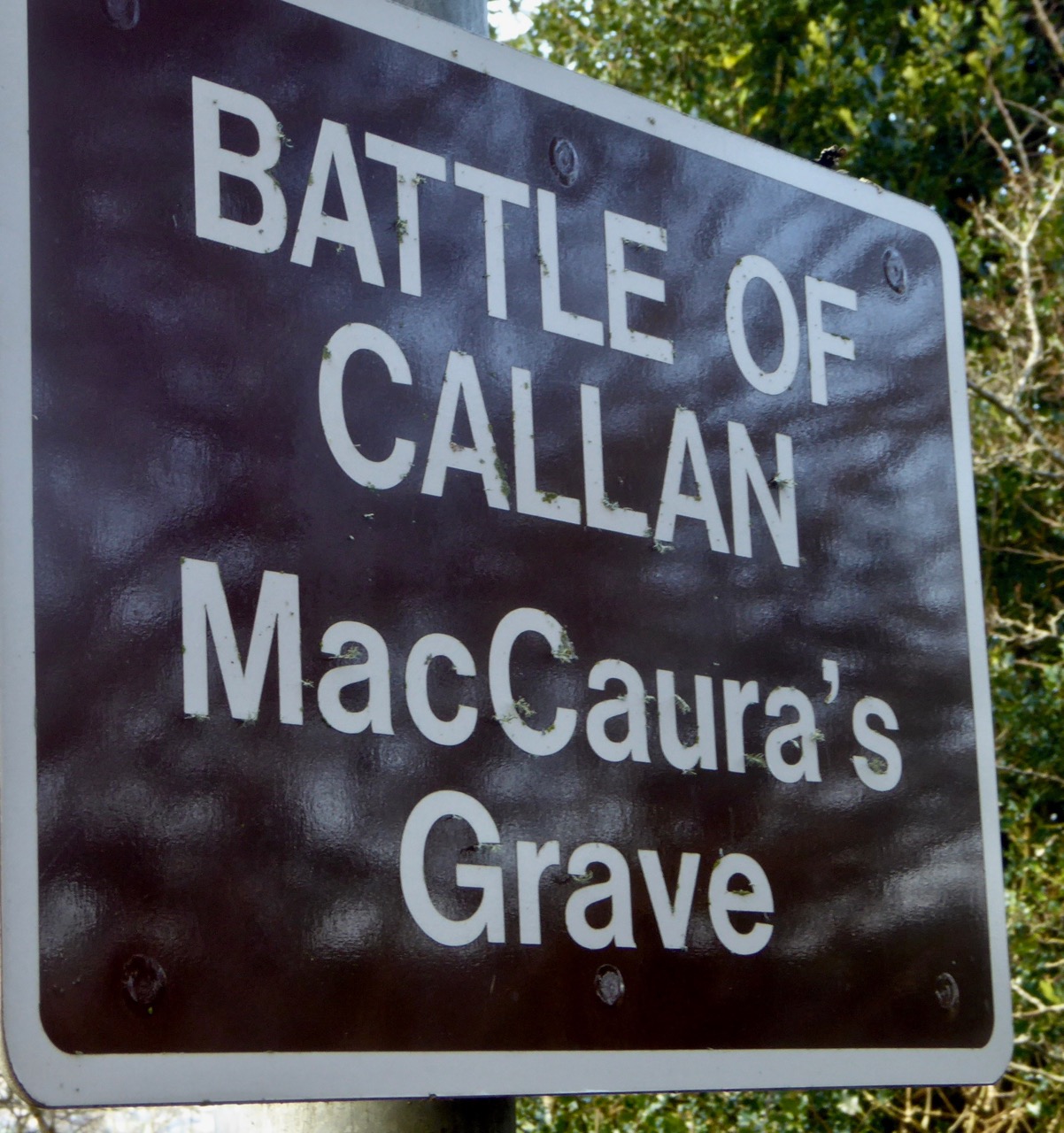

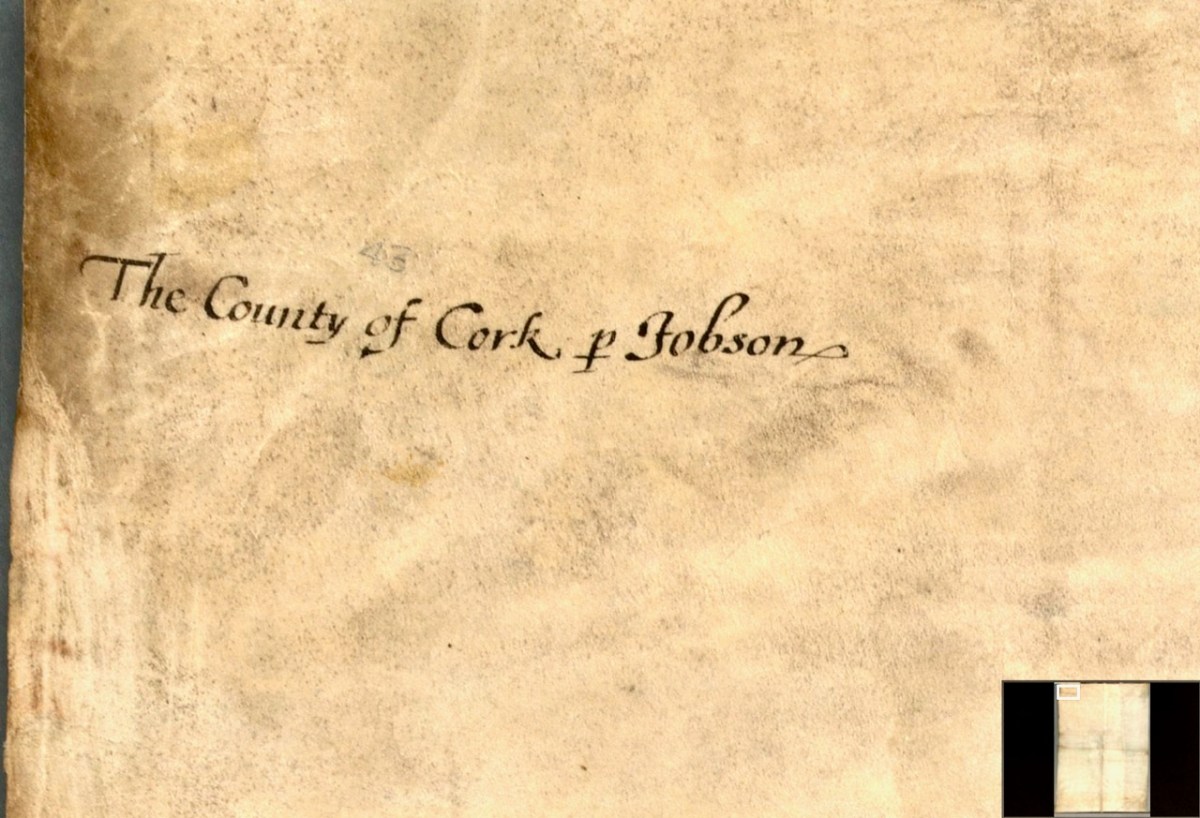

In Part 1, I said that We don’t know who did this one, or when: The date is given as 1560-1620. It seems in some ways more basic than other maps of the period, and less exact. I have now gone to the Atlas itself in Trinity College and discovered that the maps in the Digital Repository are an incomplete set. Specifically, the original Atlas at TCD contains the reverse side, the ‘verso’ of each map. Here’s what’s on the verso of the County of Cork. This:

and this:

So we see that the map is attributed to our old friend Jobson – he who drew the plantation map I wrote about here and here and which was dated to 1589. There are similarities and differences between this map and that one – the galleons and scales for example look very alike. But there’s a lot more information on the plantation map and some of it is different from our Map of the County of Cork. As to the date of the County of Cork map – we will try in this post to see if we can narrow that down a bit from the broad estimate of 1560-1620.

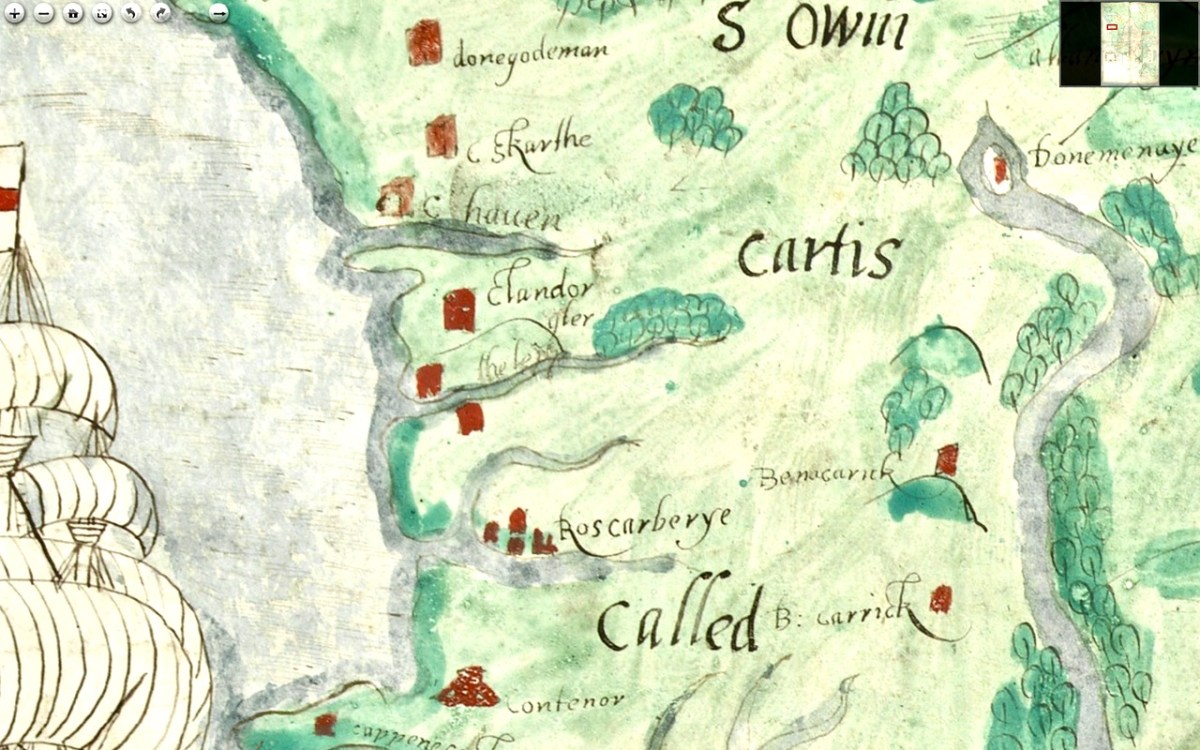

I want to go, as they say in Ireland, east along. That is, take off from where I finished last time, and travel east along the coast towards Cork, taking in the River Bandon. For the rest of this post, I’m keeping the map oriented as it is originally – that is, with west at the top (it’s actually surprising how quickly you can get used to this). Between Baltimore (Donashad) and Castlehaven (C haven), there are three castles shown, one labelled Sir Jmes Castell, Doneygodman and C skarthe. These are all a bit of a puzzle and I would invite readers to contribute ideas. On the archaeological list of Monuments for this area we can identify the O’Driscoll Castle on the Island in Lough Ine – could this be the Sir Jmes Castell? A promontory fort on Toe Head, known now as Dooneendermotmore, although likely originally an iron age refuge, was refortified in the 16th century and may, like the one I wrote about in Dunworley, have had a significant curtain wall. Was this Doneygodeman? It seems unlikely, as Doneygodeman is show inland – I wonder if instead it could be the castle at Raheen, which was a castle of the O’Donovans.

Finally, C skarthe might be a castle of the McCarthy’s – McCarthy is spelled in a variety of ways on this map, but there I can find no trace of it now. There was a castle in Listarkin, but once again, this is in the wrong place, unless this map, while certainly approximate in places, is wildly inaccurate. It seems reasonable to conclude that the more inland castles may have been harder to plot on a map that the coastal ones.

The castle at Glandore (c Landorgter) is clearly shown, along with two castles guarding the entrance to a long inlet labelled ‘the lepp.’ One may have been Kilfinnan, actually located near Glandore, which the other could possible be the coastal tower house at Downeen. This brings us to Rosscarbery (Roscarberye), shown as a collection of Buildings, as befits its status as a substantial town with a cathedral and a college, and a place of pilgrimage in the name of St Fachtna.

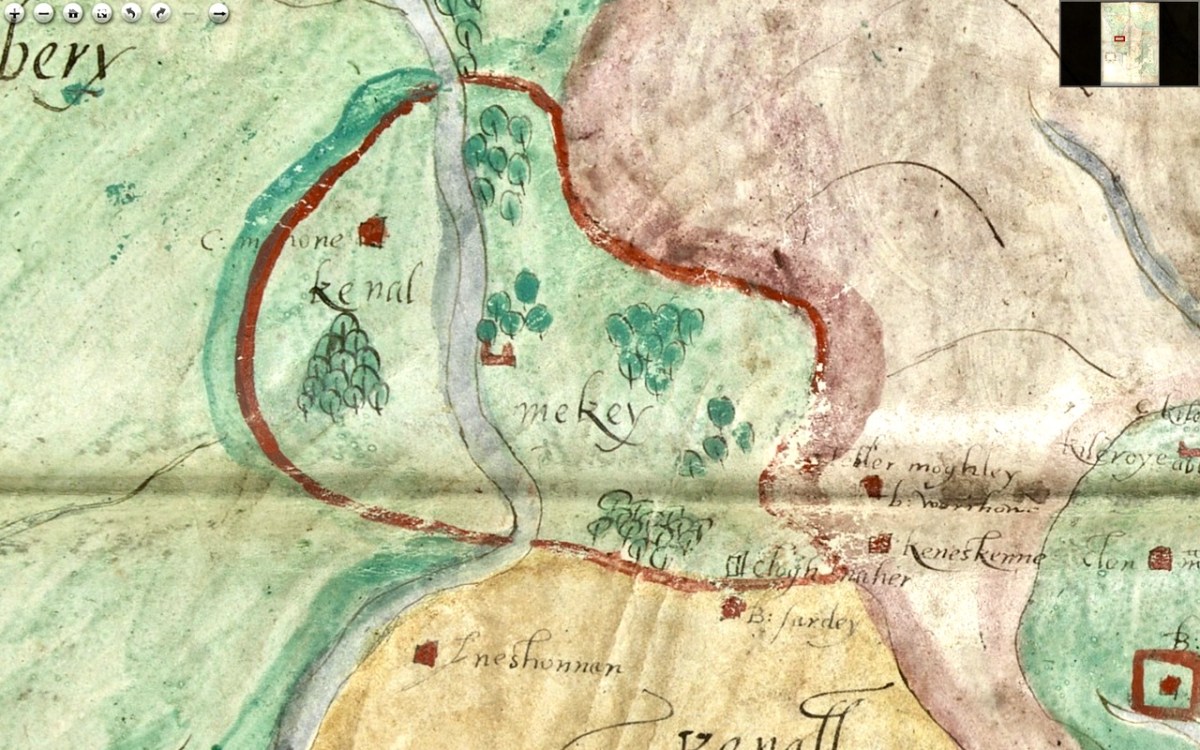

The entirety of this area, in green, is identified as Sir Owin Mc Cartis Countrey Called Carbery. Several other castles are identified here and there, and the course of the River Bandon is traced. The southernmost area is identified as Kenal Mekey, and to the south of the green-shaded section is Kennal Ley. In Canon O’Mahony’s magisterial History of the O’Mahony septs of Kinelmeky and Ivagha he states:

In the history of South Munster there is no fact attested by more abundant evidence (evidence unknown to Smith and Gibson) than that the Sept-land of the Ui Eachach Mumhan during many centuries extended from Cork to the Mizen Head, as one continuous territory, including Kinelea and Muskerry, and was ruled by a chief whose principal residence was Rath Rathleann, in Kinelmeky.

https://archive.org/details/historyofomahony00omah/page/n1/mode/2up Page 105

He identifies Rath Rathleann as the mighty multi-vallate ringfort of Gurranes, which was superseded by Castle Mahon, which stood where Bandon is now situated. And here it is, Kinelmeky, with C Mahon shown beside the river. Castle Mahon was later incorporated into Castle Bernard, home of Lords Bandon. Another Castle is shown further down the river – no doubt the one we are familiar with as we travel the N71.

We know that all this land was acquired by Richard Boyle after the Battle of Kinsale (1601) and that he started on his walled town of Bandon Bridge around 1620. Since this is still clearly identified as O’Mahony Territory I think we can take it that this map dates to before the battle of Kinsale.

We see Kenall Ley (Kinelea) in yellow, with the walled town of Kinsale at its heart. Kinsale walls were begun around 1380 and lasted until most of them were destroyed around 1690 by the forces of William of Orange. Inishannon is noted in Kinelea, as well as Park Castell (in what is now the townland of Castlelands) and finally B: Sardey (or is that a different first letter?). We know from another map in the Hardiman Atlas (below) that B designated a small town. Given that Kinsale is such a prominent walled town on this map, once again, a date before 1601 is likely.

Supporting a pre-1600 date is the fact that it is the old Irish families that are identified with their territories – no settler or Plantation names are given. In fact the O’Mahonys and McCarthys are the only names on the sections of the map we have seen so far. Moreover, it it really was the work of Jobson, we know he was actively mapping in 1589.

In Part 3 I’ll do a quick meander through the most interesting parts of the rest of the map. Stay tuned.