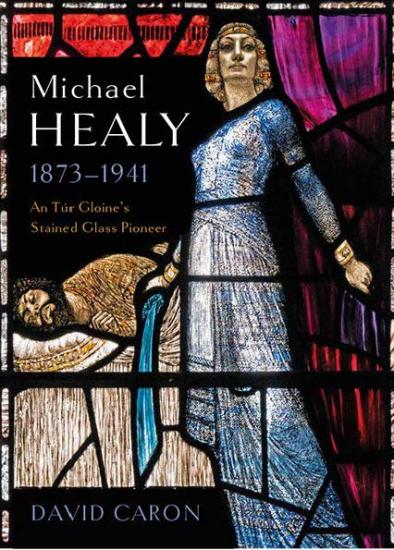

This book – MIchael Healy: An Túr Gloine’s Stained Glass Pioneer – is nothing short of a miracle. It’s beautifully written by David Caron, with superb photography mainly by Jozef Vrtiel, and outstanding production values by Four Courts Press. But a miracle? Yes – because David Caron uses his scholarship and knowledge of stained glass as well as the history and art movements of the period to produce an immensely readable book about an intensely private man who left behind practically nothing about his life except his magnificent work.

I will declare an interest right away – David Caron is a friend and mentor, editor and principal writer of the Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass, to which I am one of the contributors. I have been looking forward to this book for a long time, as have all his friends, colleagues and collaborators. It was launched to great acclaim in Dublin on November 1 – all the available copies were snapped up at the launch, including mine (stowed behind the desk), so I had to wait until December to get my hands on it.

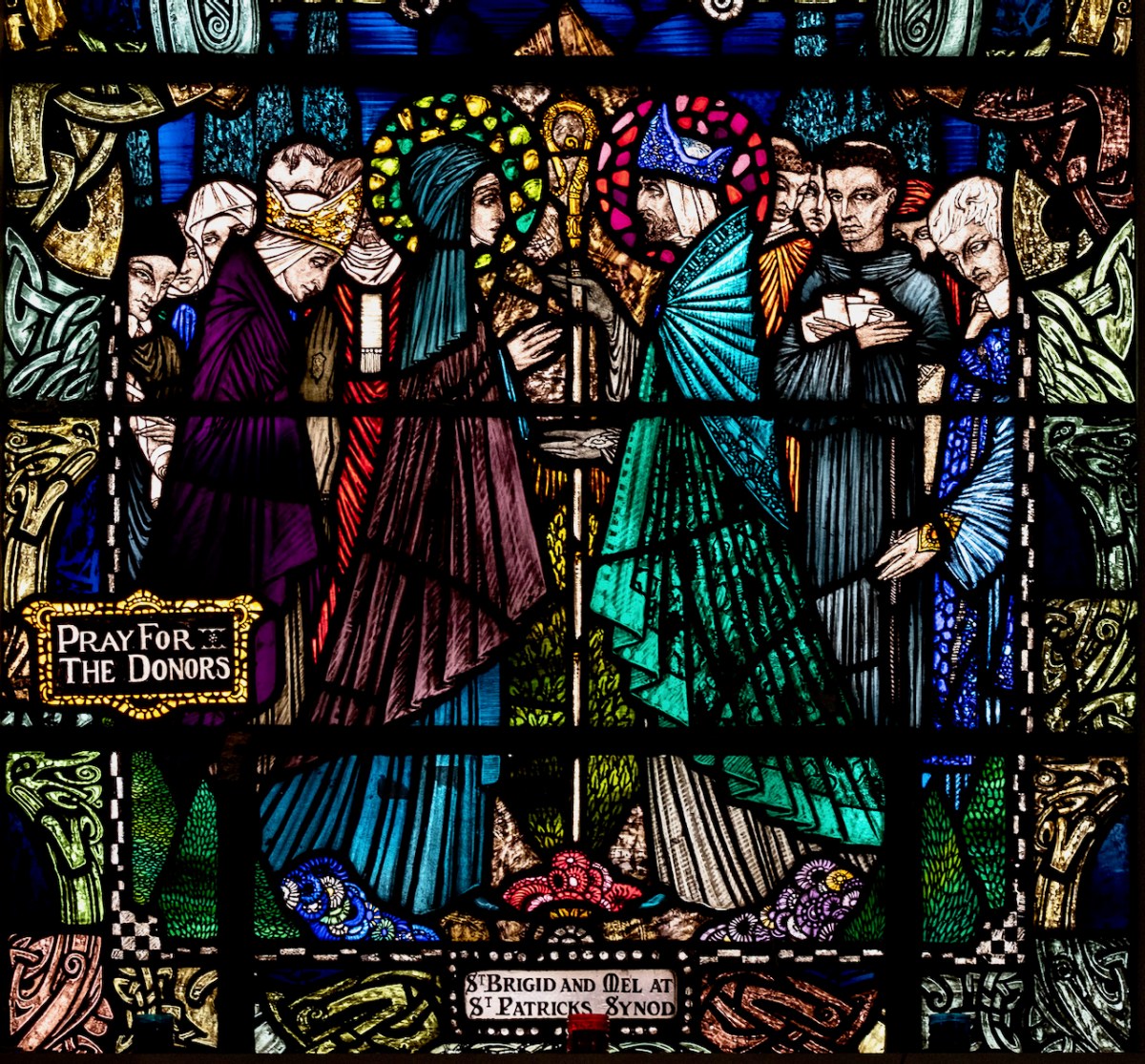

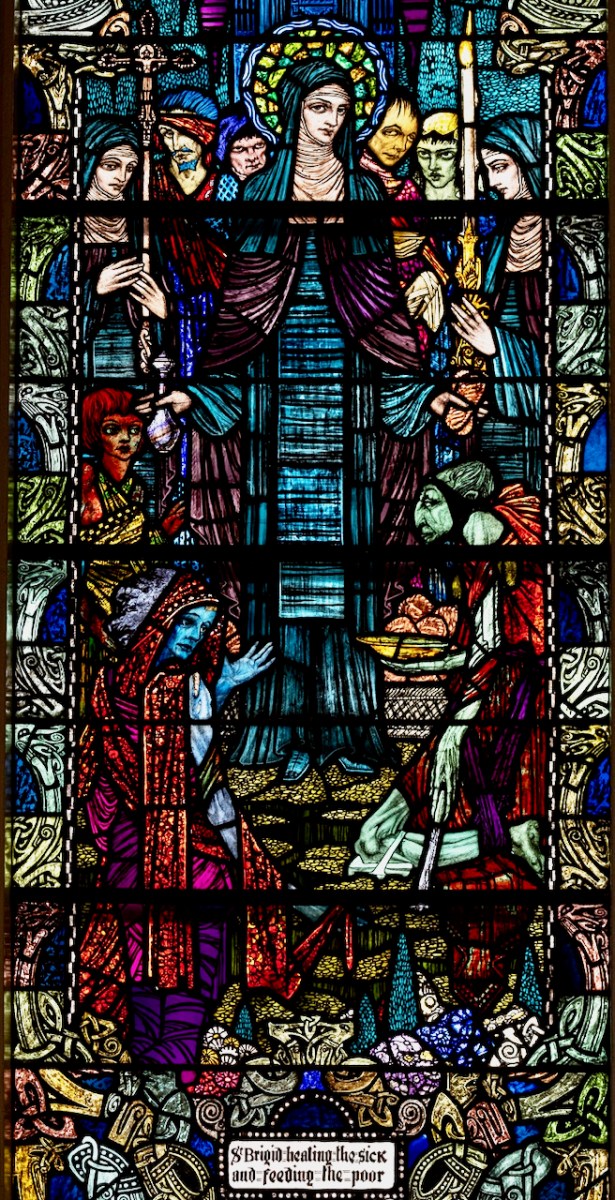

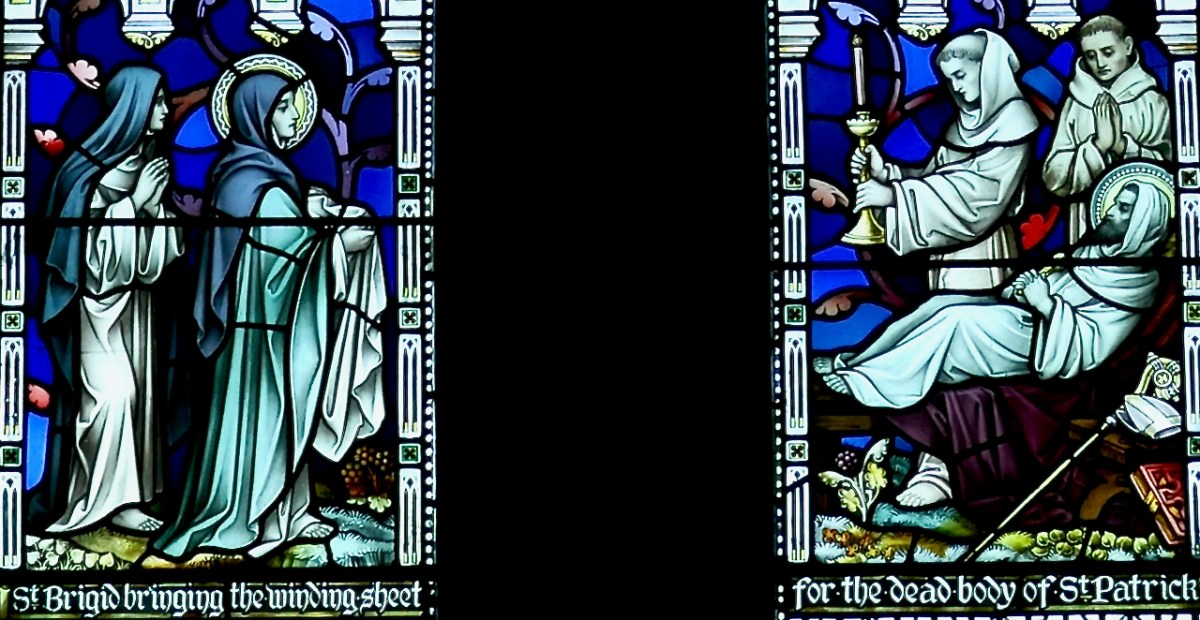

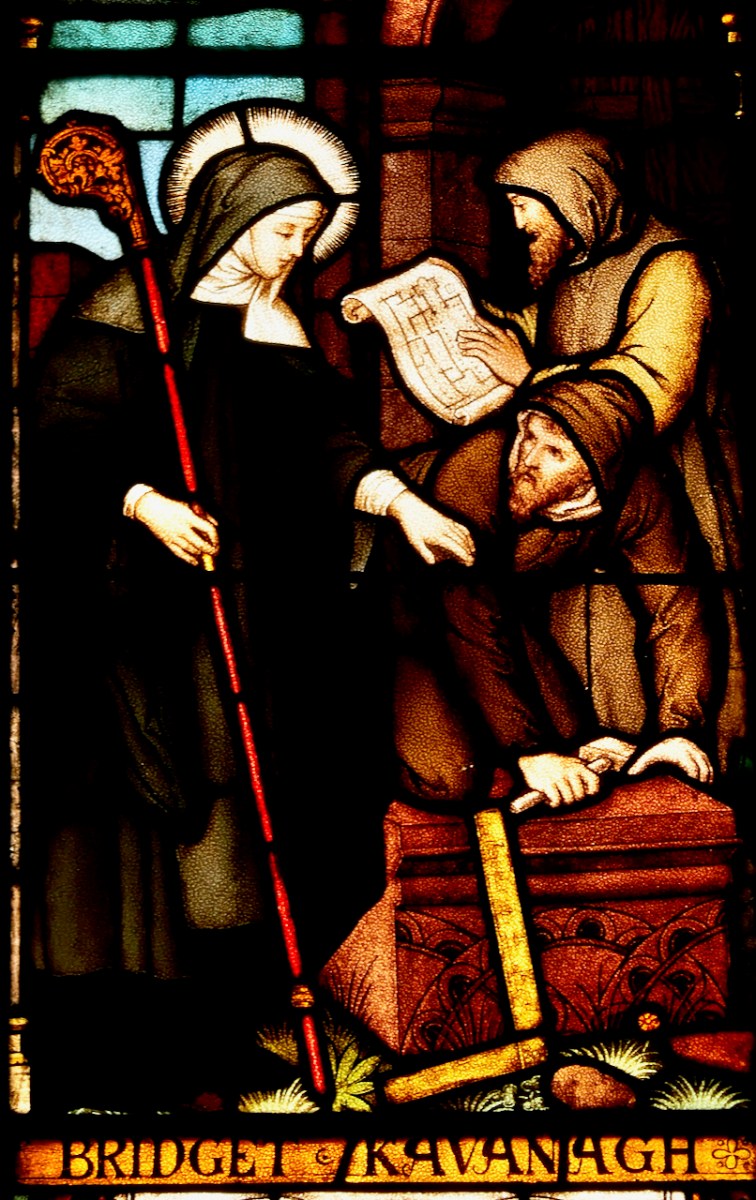

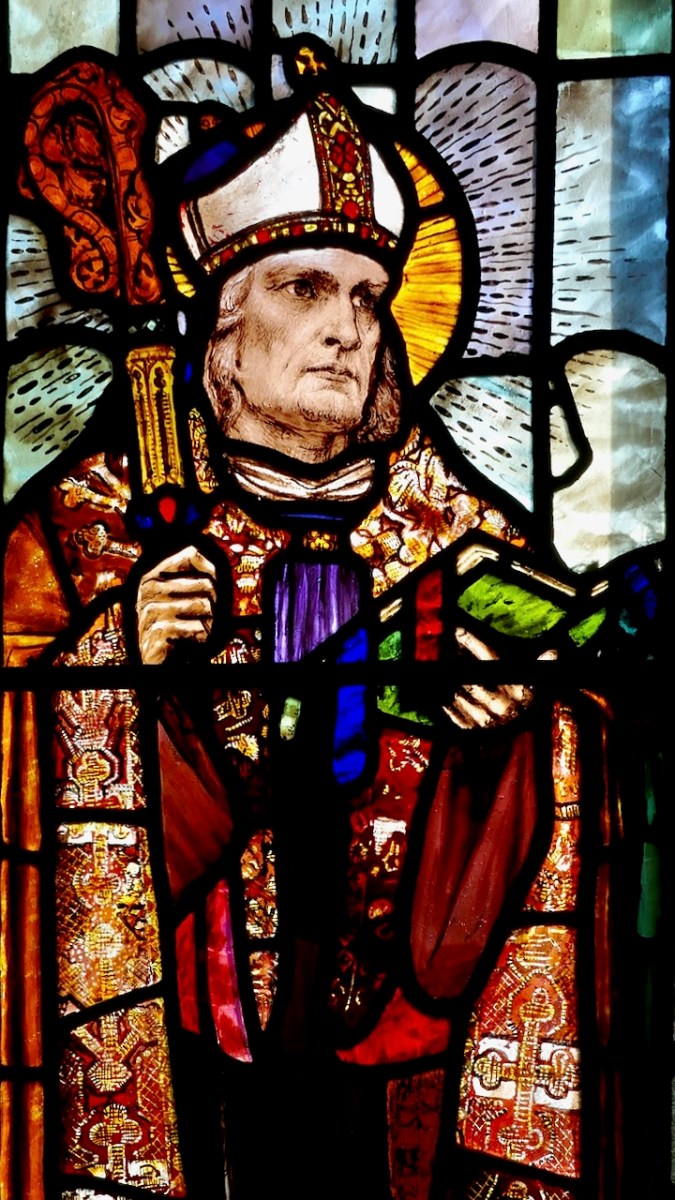

From a private bishop’s oratory, Sts Macartan, Brigid, Patrick and Dympna. Detail of Macartan, below. The rich reds and yellow shading of Macartan’s robes are the result of aciding and silver stain, described further down

All the photographs in this post are my own – but I haven’t seen that many Healy windows, and my photography does not bear comparison with Jozef’s magnificent images. The book is profusely illustrated – it’s one of its many strengths – with many photographs of the tiny details in which Healy delighted and which distinguish his windows from those of other artists. Healy spent all his working life at An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass) the Studio founded by Sarah Purser. If you are unfamiliar with this period in Irish stained glass, you might like to read my post Loughrea Cathedral and the Irish Arts and Crafts Movement before continuing.

Born in 1873 into grinding poverty in a Dublin tenement, through a combination of great good luck and his own prodigious talent and hard work, Michael Healy turned himself into one of the foremost stained glass artists of his time. Reading David’s account, it is difficult not to be overwhelmed at times by the hardship endured by Healy and his family in turn-of-the-20th-century Dublin. Packed into one room with miserably inadequate sanitation, whole families succumbed to disease and early death. Consumption was rampant and the only recourse for anything approaching treatment was the dreaded workhouse. Infant mortality rates were high and so we read about several Healy babies who failed to survive into adulthood, as well as adults carried to early graves, leaving widows and widowers to try to cope.

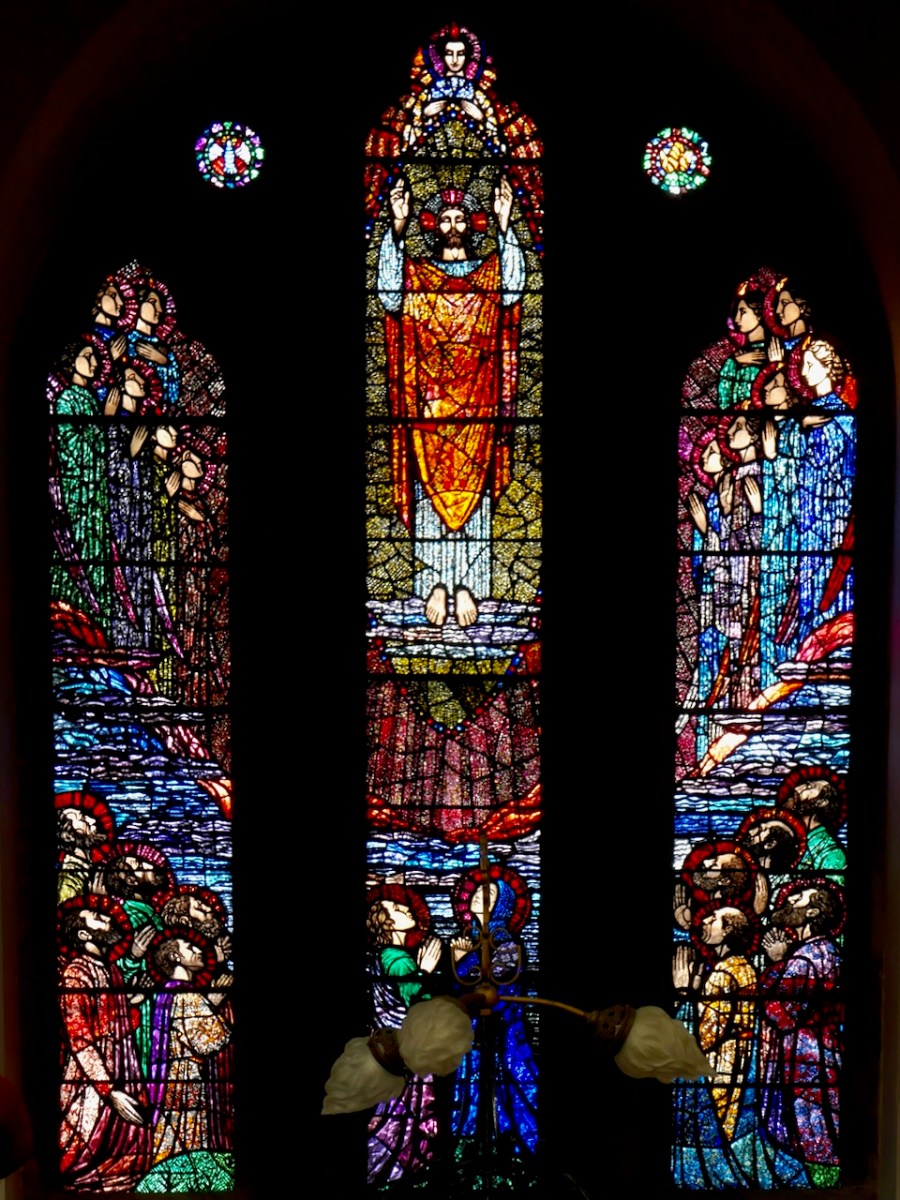

Christ with Doubting Thomas, St Joseph’s, Mayfield, Cork

In the midst of all this was the First World War, the Easter Rising, the War of Independence and the Civil War, followed by the emergence of the new Irish State. David chronicles all of this, and the effect it was having on citizens, like Healy, who were trying to go about their business, but who also had deep convictions about politics and religion.

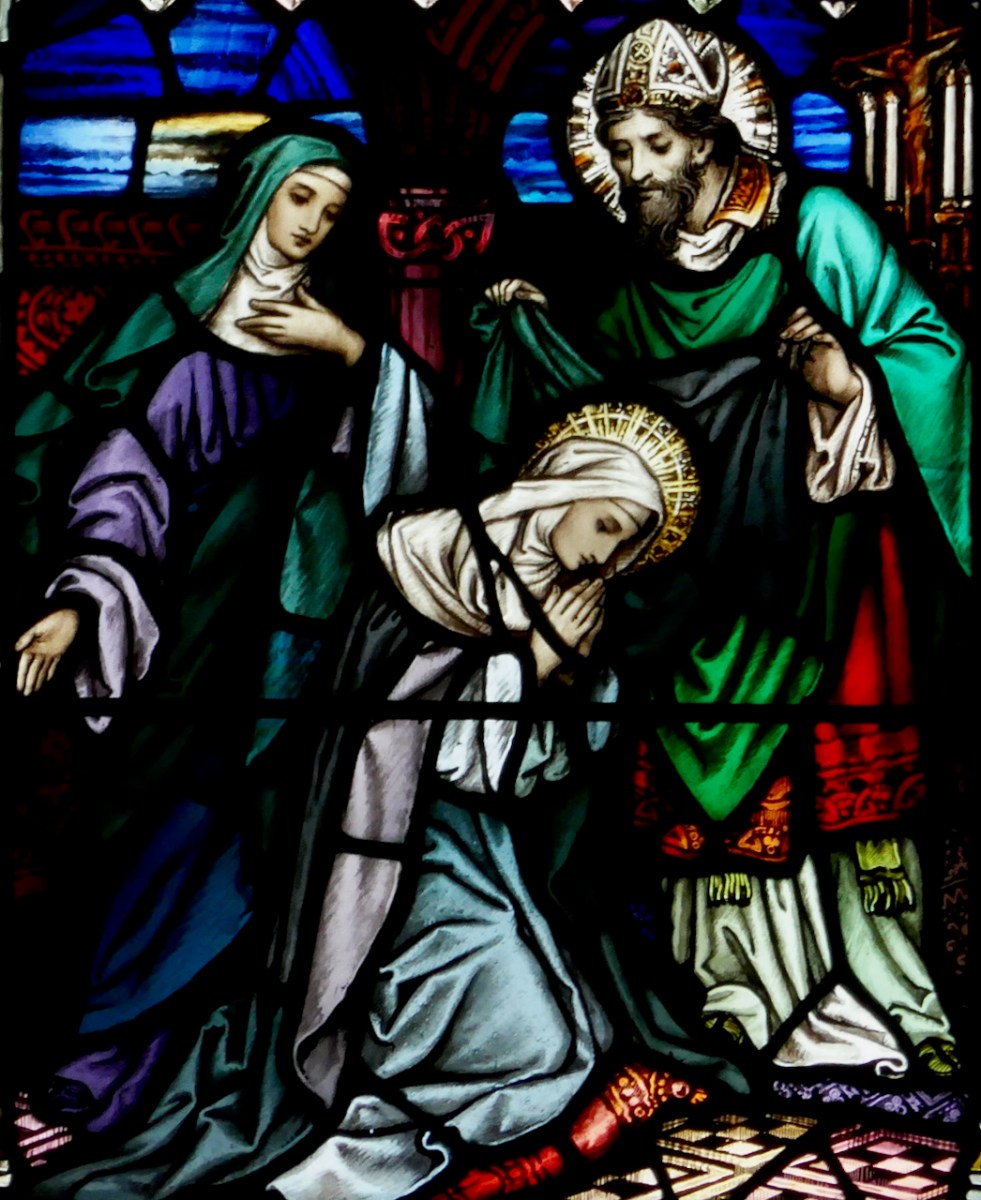

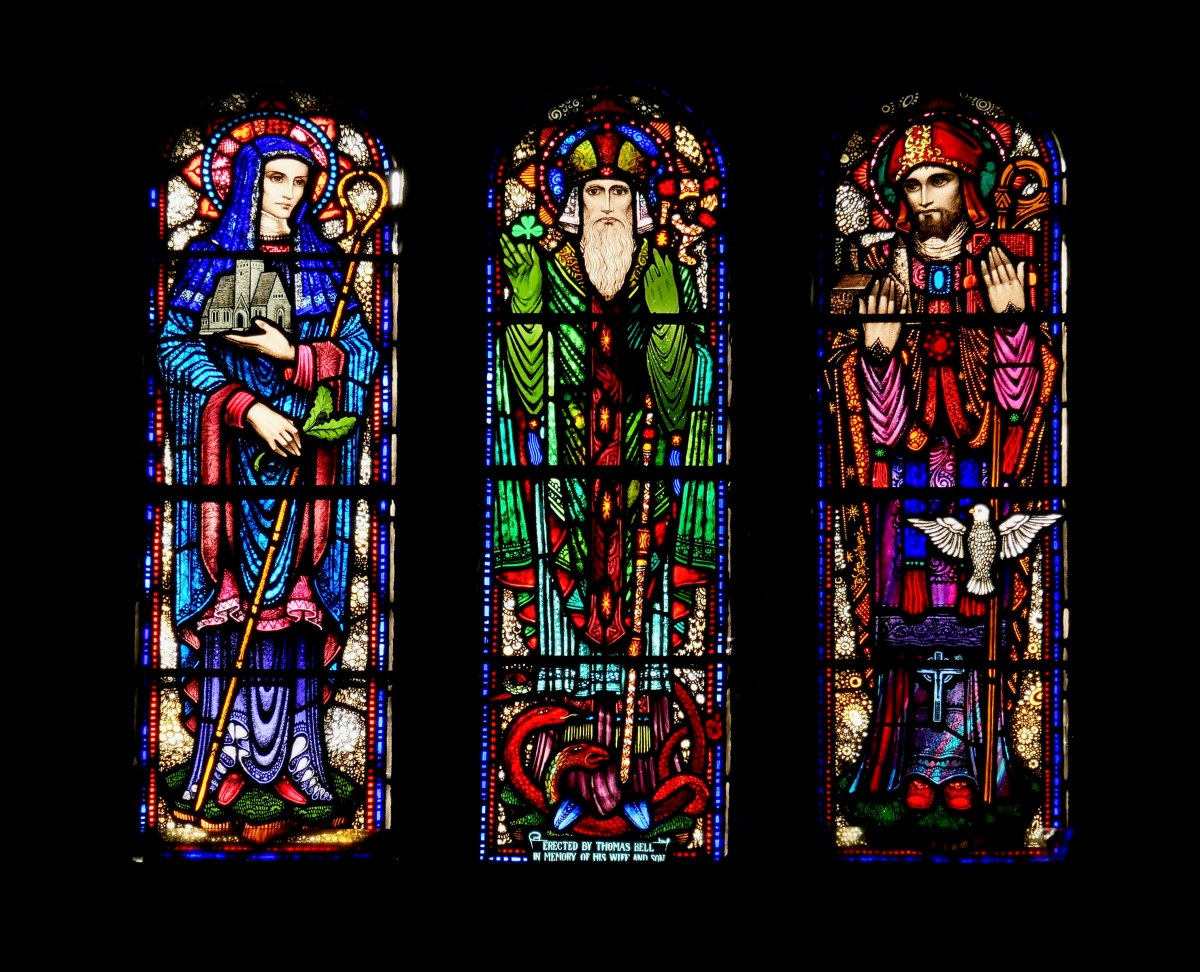

These windows, Sts Brigid, Patrick and Columcille, are in the National Gallery

In some ways, Healy was a typical young man of his time. Deeply religious, he spent some time in a seminary before deciding he was unsuited to the vocation. He belonged to a Catholic men’s lay organisation. David provides many instances where his working class Dublin accent, his republicanism, and his Catholicism must have put him at odds with his fellow artists at An Túr Gloine, mostly female, Protestant and from well-to-do backgrounds. They found him brooding and introverted, although they acknowledged his exceptional talent, and until Evie Hone arrived he did not make true friends with any of them.

The Annunciation, Loughrea Cathedral. This window was closely based on a design by the great arts and crafts stained glass master, Christopher Whall. Whall came over from England to supervise the execution of it by the Túr Gloine artists, including Healy. Celtic revival interlacing was very popular at the time, and a way of putting a nationalistic stamp on a window – note the subtle inclusions of interlacing here and there

I mentioned that he had strokes of good luck in his life, two in particular. One was the patronage of a perceptive priest, Fr Glendon, who enabled him to study in Florence for a period of time and who procured illustration work for him in Dublin. David points out here and there in the text the influence of Italian painters discernible in Healy’s windows, gained from his sojourn in Italy.

Detail of a Patrick window in Donnybrook

The other was that he found lodgings with a landlady, Elizabeth Kelly, and over time they grew close. Eventually, they become lovers and had a son, Diarmuid, together. Although the relationship was never publicly acknowledged (she was married, although her husband left her) it provided both of them with stability and comfort, and Healy was close to his son. In the 30s Diarmuid O’Kelly (although his mother went by Kelly) bought a Ford Model T and he and Michael would go on sketching expeditions up into the Dublin Mountains and out along the canals.

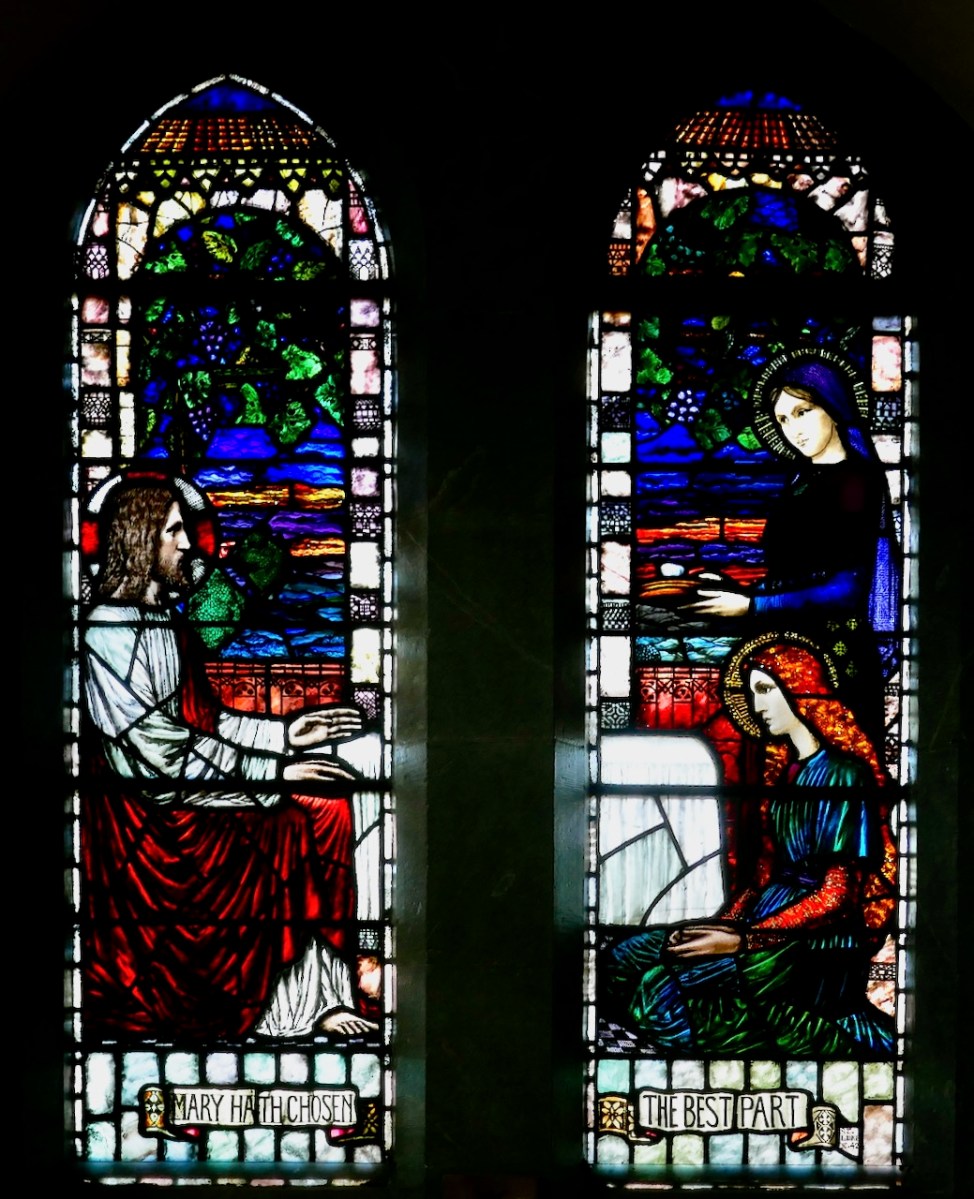

Christ with Mary and Martha, Mayfield, Cork

Because of the opprobrium that such a scandal would have visited upon both Elizabeth Kelly and Michael Healy, Diarmuid was never told that Healy was his father, but he must have suspected, and in more recent times DNA testing confirmed the relationship. Reading about the frequent tragedies that befell the Healy family and the privations under which he grew up, I find it very comforting to know that Michael enjoyed the security and love of his adopted family as he got older.

St Simeon, one of Healy’s early windows for Loughrea Cathedral

David leads us on a measured journey through Healy’s life and work. He was the first recruit to An Túr Gloine, Sarah Purser’s stained glass studio, and later co-op. There, he worked alongside AE Child (also his instructor at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art), Catherine O’Brien, Beatrice Elvery, Ethel Rhind and Hubert McGoldrick. All of them looked up to him as the finest painter at the Studio. He, in turn, admired the work of Wilhelmina Geddes, and when her health caused problems he finished some of her windows, trying to respect her style and designs. But it wasn’t until Evie Hone arrived that he found a true colleague – Nikki Gordon Bowe described Hone as “his devoted disciple and admirer” and she finished some of his windows after he died.

Healy designed many Patrick windows – this one is in Glenariff Co Antrim

Each commission is described and through David’s detailed accounts we come to understand Healy’s style – what iconography he was attracted to, how he decided on the myriad details with which he embellished his windows, and most of all, his decorative methods.

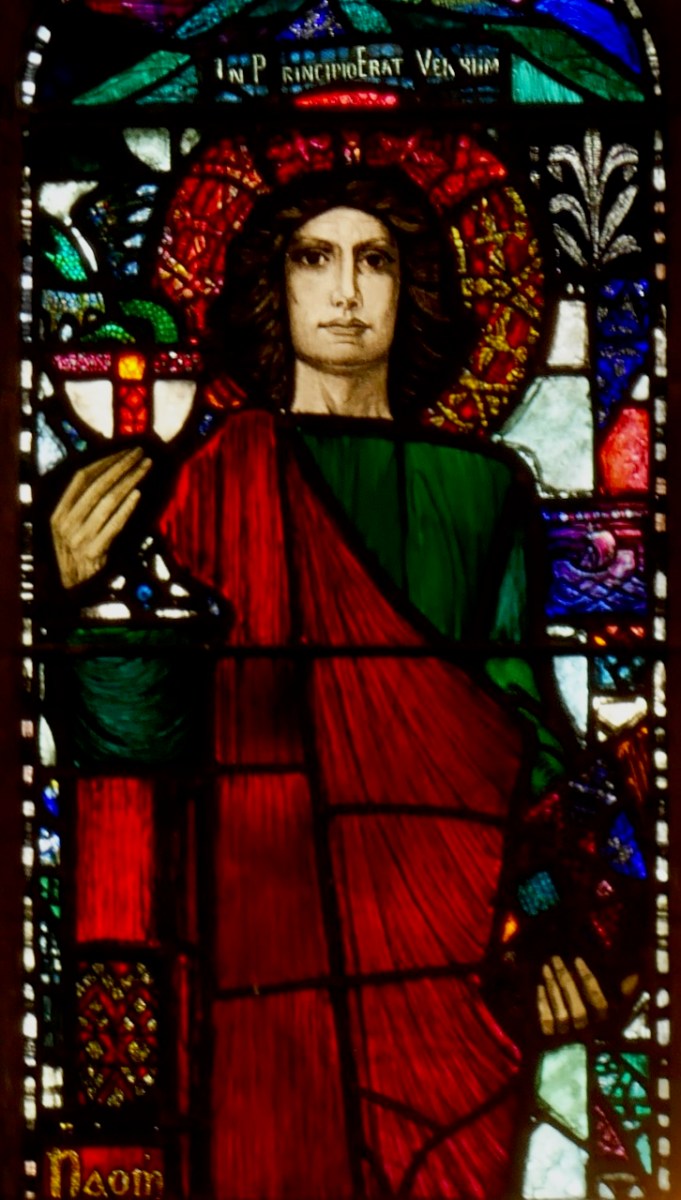

John the Evangelist, Loughrea Cathedral

Long before Harry Clarke made it is his signature, Healy was a master of aciding, a difficult (and dangerous) process used to remove colour from the surface of flashed glass. Flashed glass is clear glass which has a skim of coloured glass fired onto its surface. This top layer could be removed by scratching or etching it away, or by immersing the glass in a bath of hydrofluoric acid, having first applied beeswax to any surface where the colour should remain intact. By waxing and immersing, often several times, colour could be altered from, for example, a rich ruby red to the merest hint of pink, and all shades in between.

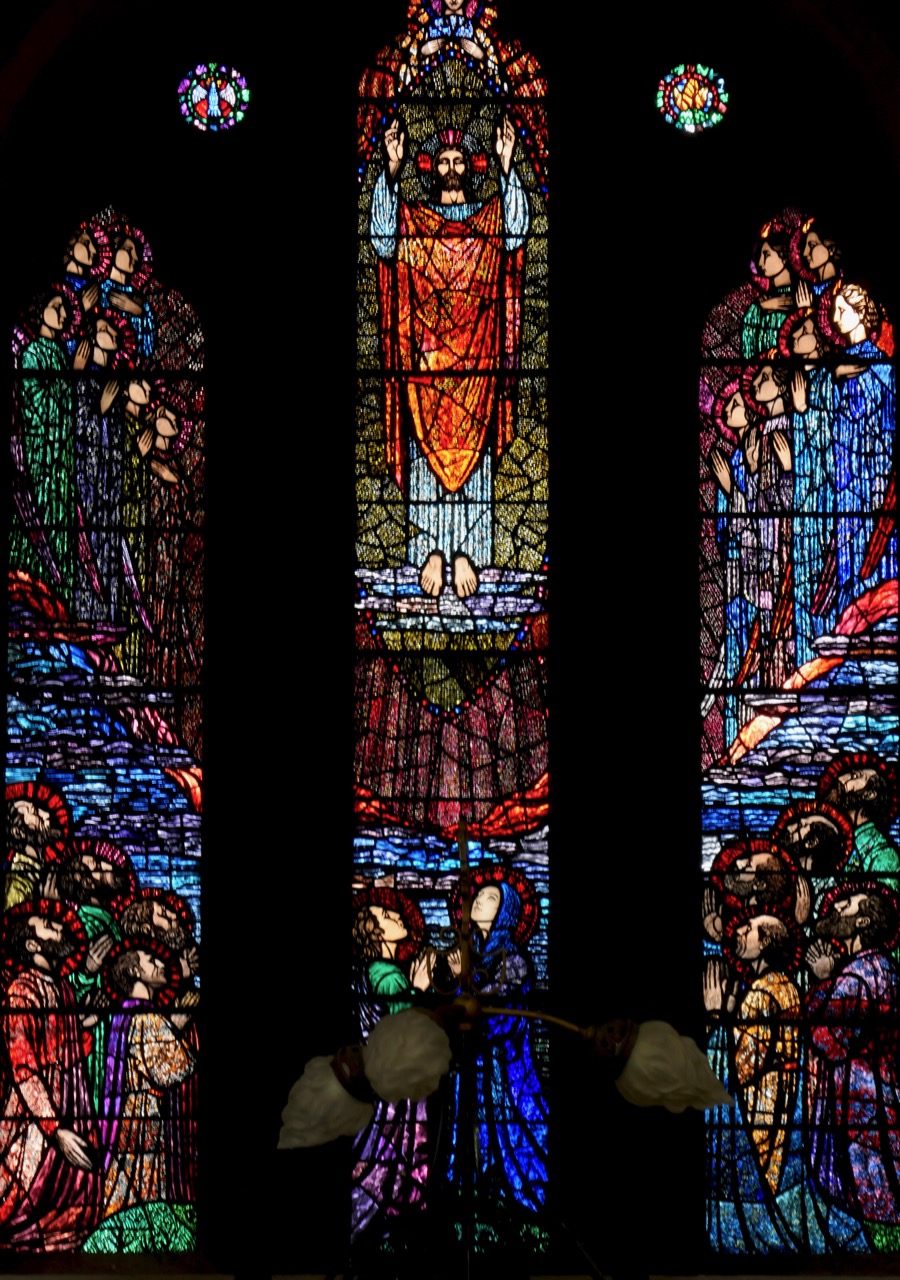

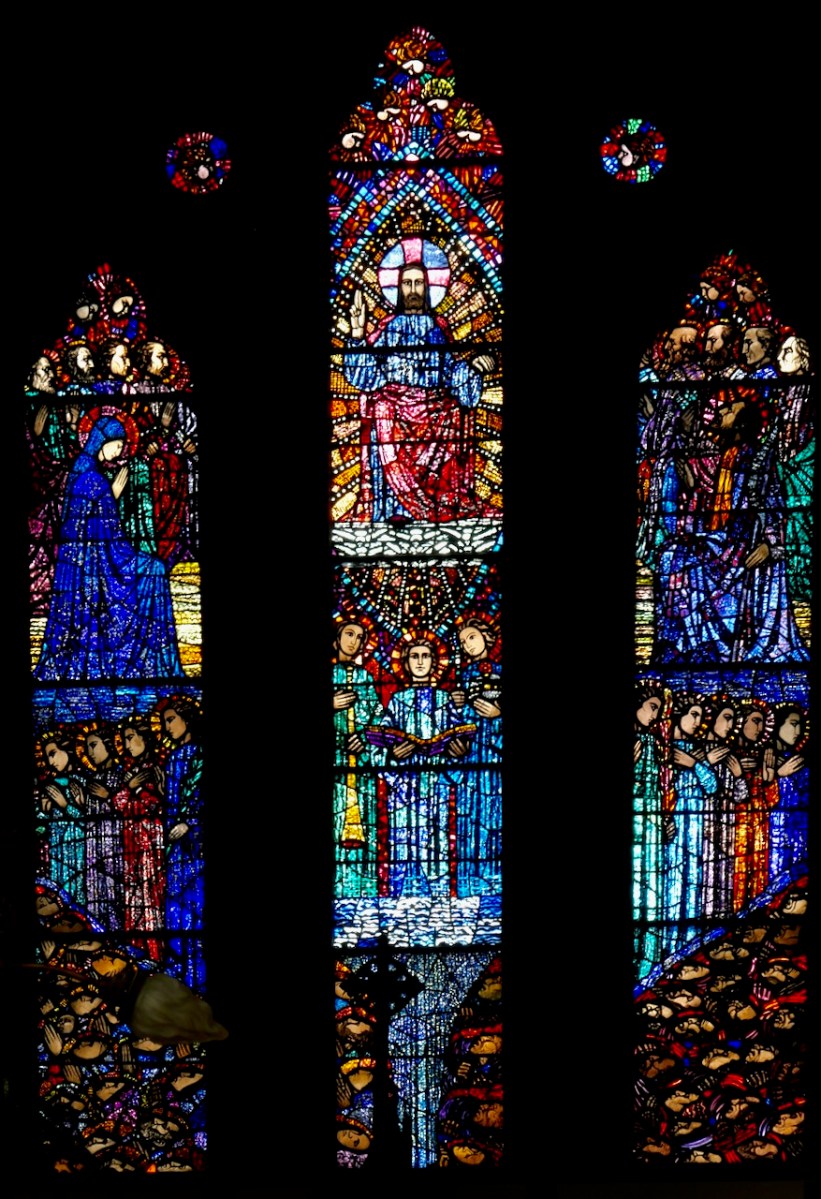

Healy’s Ascension, in Loughrea Cathedral

Healy would often plate two sheets of glass together – for example, one red and the other blue – each one carefully acided, and could by this means achieve an astonishing array of colours from the red-blue side of the spectrum. Added to this, he would often use silver stain on the back of the glass. Once heated in the kiln, the silver stain would permeate the glass, turning it yellow (repeated firings could deepen this from bright yellow to a rich amber colour). Finally, all the figuration would be painted and stippled on to the surface of the glass and the individual pieces of glass would be assembled and leaded together to produce the finished window. Healy was a perfectionist and Purser would despair of ever making enough money to keep the studio going since he spent so long on each commission.

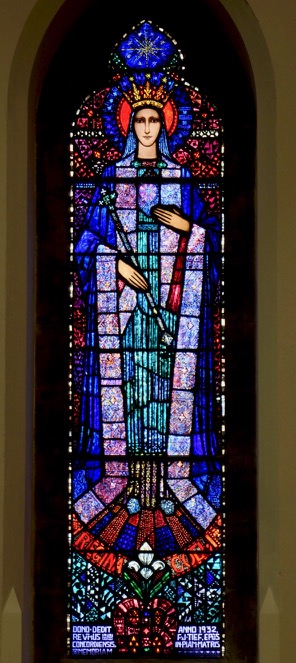

This detail from Healy’s Virgin Mary window in Loughrea illustrates well his aciding technique using red and blue flashed glass plated together to produce not only infinite shades of colour but a sparkling jewel-like effect

It is through David’s lively analysis of each window that we truly come to appreciate Healy’s genius and his evolution as an artist, his style developing according to his exposure to more modern influences.

Considered one of his masterpieces, this is the Last Judgement Window in Loughrea, completed towards the end of his life. A detail from The Damned (right -hand light) is below

David wears his erudition lightly and when he dissects a window, pointing out elements that are easy to miss, and explaining what they mean and why Healy used them, I found myself pouring over Jozef’s wonderful photographs, picking out each separate item of iconography, and marvelling anew at the depths of learning that Healy brought to his designs. For example, David devotes five pages to the St Augustine and St Monica window in John’s Lane Church in Dublin and not a word is wasted.

Along the way we meet a host of characters – the redoubtable Sarah Purser and his colleagues at An Túr Gloine, enterprising priests and bishops, citizens memorialising their dead family members (CS Lewis!), art critics such as C P Curran, American heiresses, patrons of the arts, Celtic Revival influencers (OK, modern word, but you know who I mean). We get insights into the inner workings of the studio, wherein frequent bouts of unprofessional behaviour created tensions, and where Sarah Purser often had to crack the whip when productivity lagged. We come to understand the difficulties of soliciting business, agreeing on final designs and delivering orders, especially to overseas clients, in days when postal service to American and New Zealand took weeks.

A detail from the Patrick window in the National Gallery

We also come to see Healy as a rounded artist who did more than stained glass. His quick sketches of Dublin characters, drawn from life have all the attraction of immediacy and familiarity, while his watercolour landscapes are charming.

An early Loughrea window, Virgin and Child with Irish Saints

Healy died in 1941. By the time you finish the book, you feel you have lost a friend – a difficult and complicated one to be sure, but one whom you admire and will never forget. While obviously a gruff character on the outside, David allows us access to his humanity, and points out the obvious sympathy with which he portrays some of his subjects. His Loughrea St Joseph (below), for example, shows, in the words of the art critic Thomas McGreevy, a “Joseph who knows the tragedy of the world and who has some special understanding of the destiny. . . of the child”. We are, of course tempted to see in the tenderness with which Joseph gazes down at Jesus a revelation of Healy’s suppressed feelings for his own son.

This book is not just for stained glass enthusiasts, though they will delight in it, but for anyone interested in life in Ireland at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, and indeed for anyone who enjoys good writing and a story that propels you through almost 70 years of the life of a significant artist. Available from the publisher or in all good bookstores.