This week I fulfilled a long-held ambition – to visit Corpus Christi Church in Knockanure, Co Kerry.

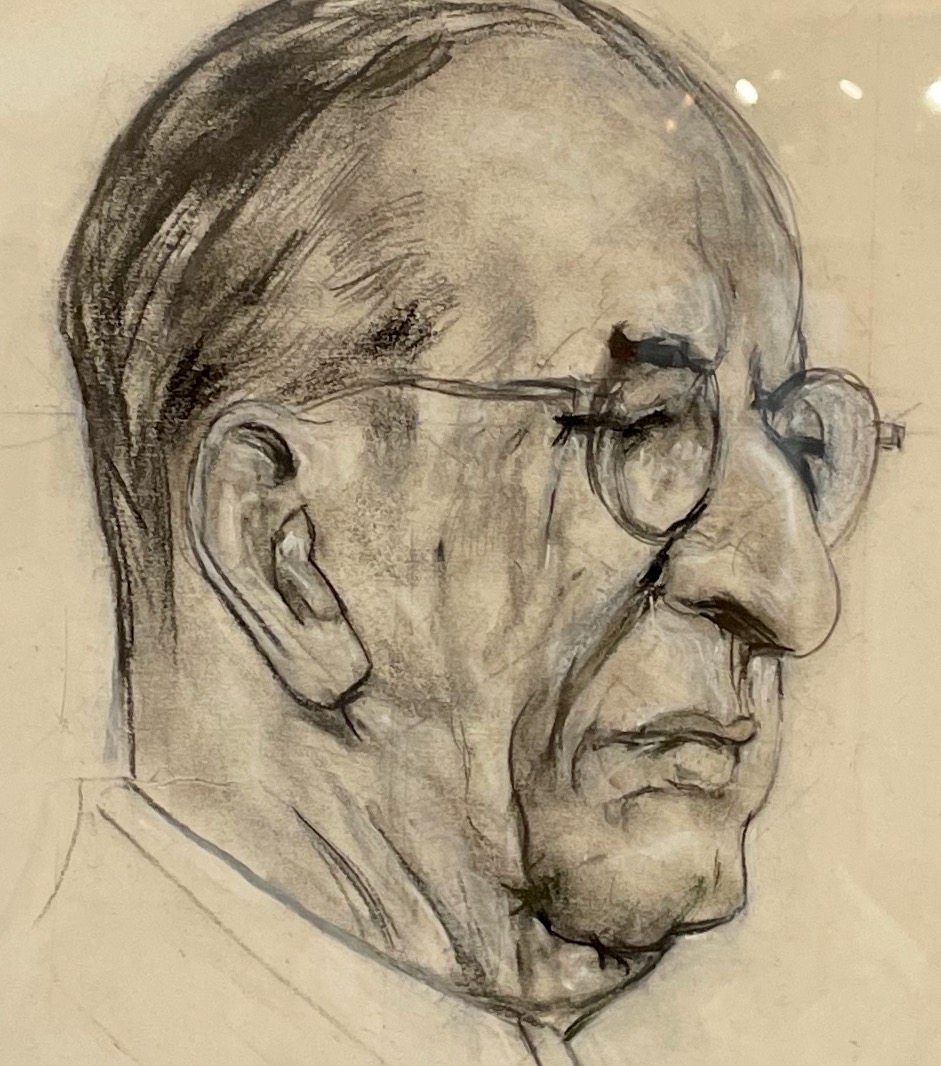

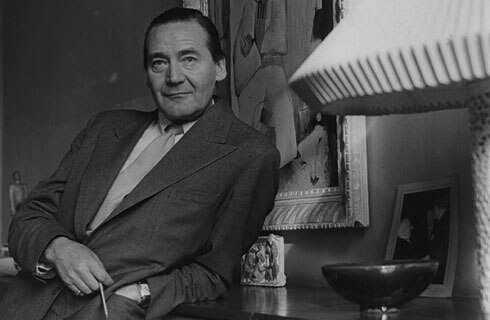

This was one of Ireland first modern churches, built in 1964, and designed, depending on which authority you read, by Michael Scott or by his partner, Ronnie Tallon. At any rate, it was certainly the work of what is now, since 1975, the architectural practice of Scott Tallon Walker, still going strong. Michael Scott, according to Richard Hurley in his outstanding book Irish Church Architecture, was “the leading architect of his generation.” The black and white photos of Knockanure in this post are from that book. Meanwhile Ronnie Tallon was “one of the most influential Irish architects of the last century”.

Hurley assigns the design to Michael Scott, while this piece from RTE (source of the second quote above) declares it to be the work of Ronnie Tallon. I am convinced by the latter, having read Stony Road Press’s artist description and statement by Ronnie Tallon, in which he talks about his obsession with the simplicity of the square and with the work of Mies van der Rohe.

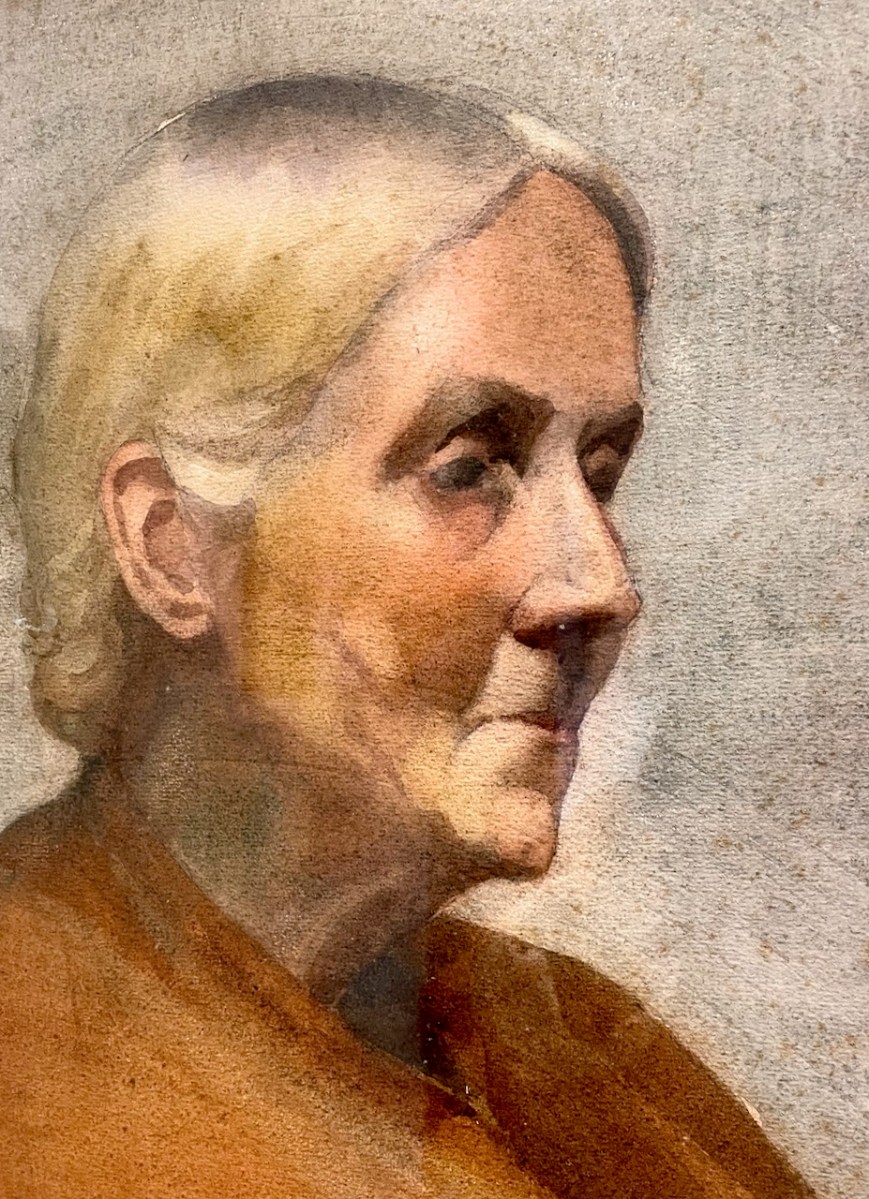

But Scott (above), as the head of the practice was undoubtedly involved. Hurley tells the story of how the commission was won:

The whole project was a bold intervention by Michael Scott who, when he was asked to design the church, was required to seek approval from the people of the parish. This he succeeded in doing at a meeting which was held in the local school attended by the head of each family. Nobody before or since had dared to construct a church of such rigid discipline which, in spite of its small scale, raises itself above the surrounding countryside.

This is a profoundly rural area in North Kerry, and yet it is home to a number of modern, innovative churches. Knockanure was the first, indeed one of the first in Ireland. Is there something in the water, that produces such forward-thinking parishioners who can see beyond the confines of gothic arches and rose windows? I don’t know, but I made sure to drink lots of water during my visit to North Kerry.

Photo above by Amanda Clarke

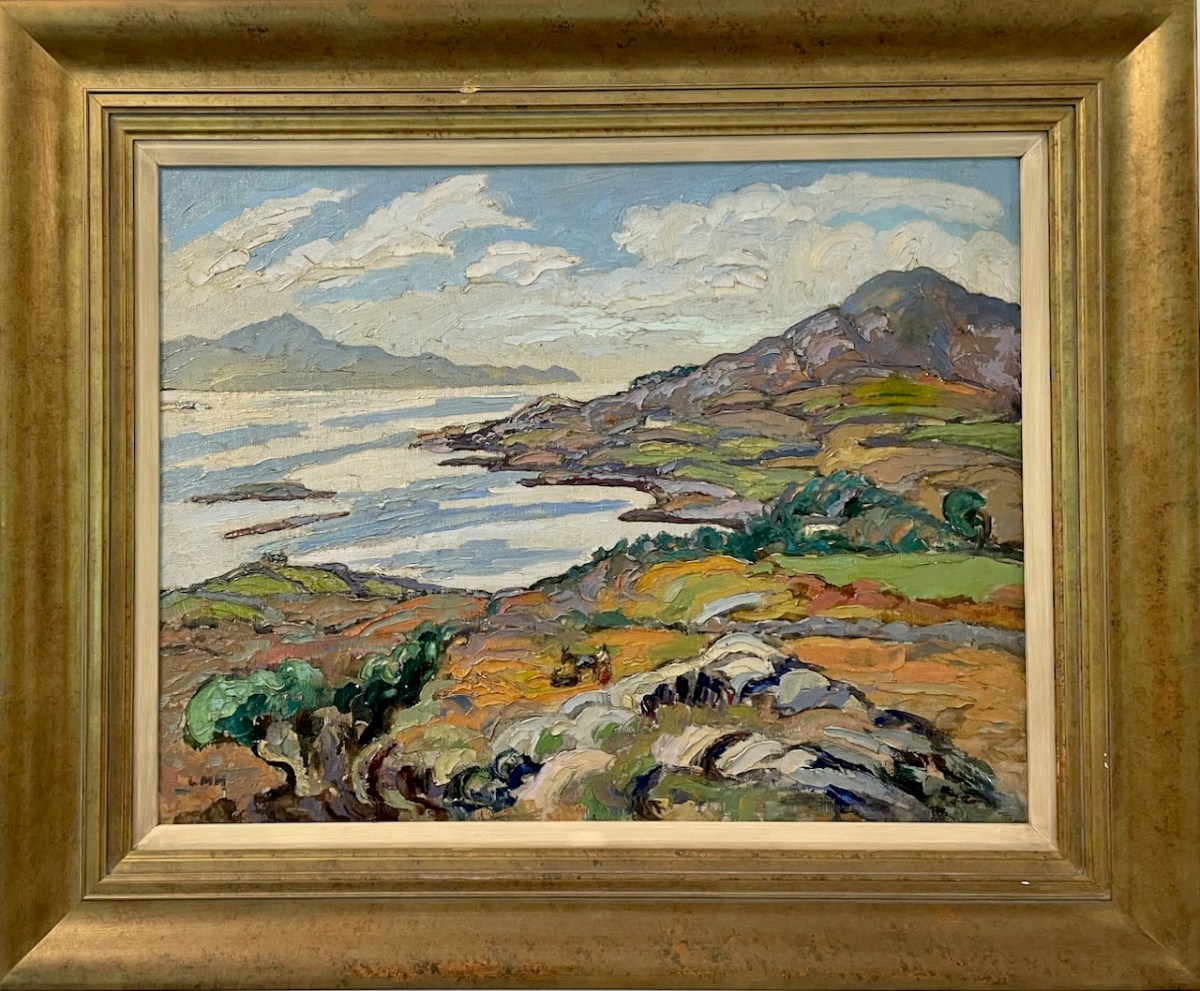

Hurley describes Corpus Christi as a building of absolute dignity and simplicity, but one which at the same time had little or no sympathy with the Kerry landscape. I’m not sure I quite agree with the second part, since the area around Knockanure is flat and low-lying. The church appears to be built on a platform, with steps leading up to the front, so that it is clearly visible on the landscape.

The church is indeed rigidly disciplined – a rectangle that gives the appearance of a light and airy open box. Two panels, one at the front and one at the back, delineate the worship space, while clerestory windows created by the roof beams allow light to pour down the side walls. The back panel conceals and makes space for the sacristy.

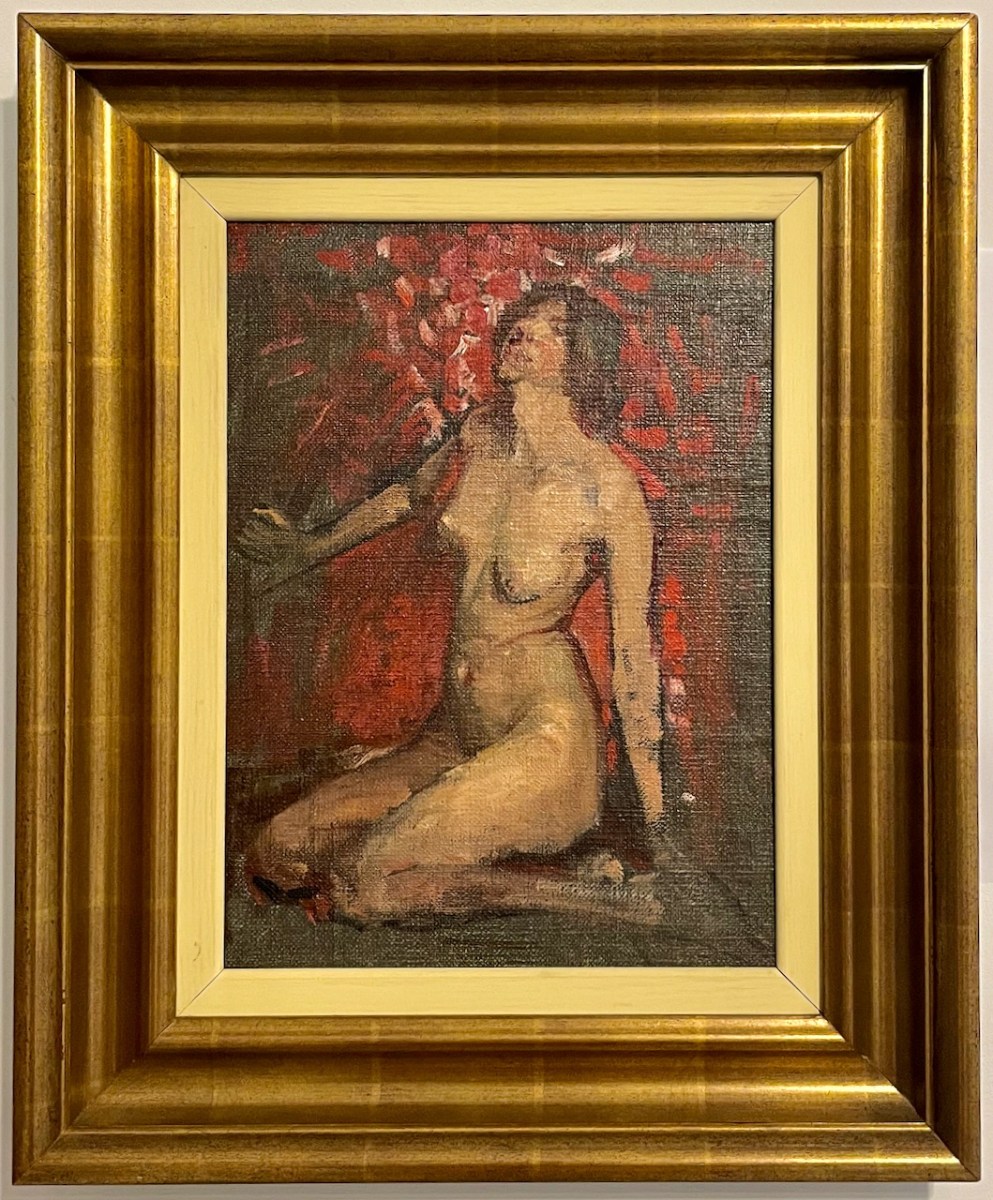

The church furniture, all part of the original 1960s design, enhance the simplicity and the unity of the design, from the black marble altar and fonts to the low, beautiful benches.

In keeping with the directives of Vatican II, the church incorporated work by some of the finest artists of the time. The front panel is in fact a large-scale sculpture, in wood, of the Last Supper, by Oisín Kelly. It is the first thing you see when you enter, immediately heralding a devotional space. The back of the panel holds two confessionals.

The cross is by Imogen Stuart, as is the carved wooden Madonna and child statue. Imogen died last year, aged 96.

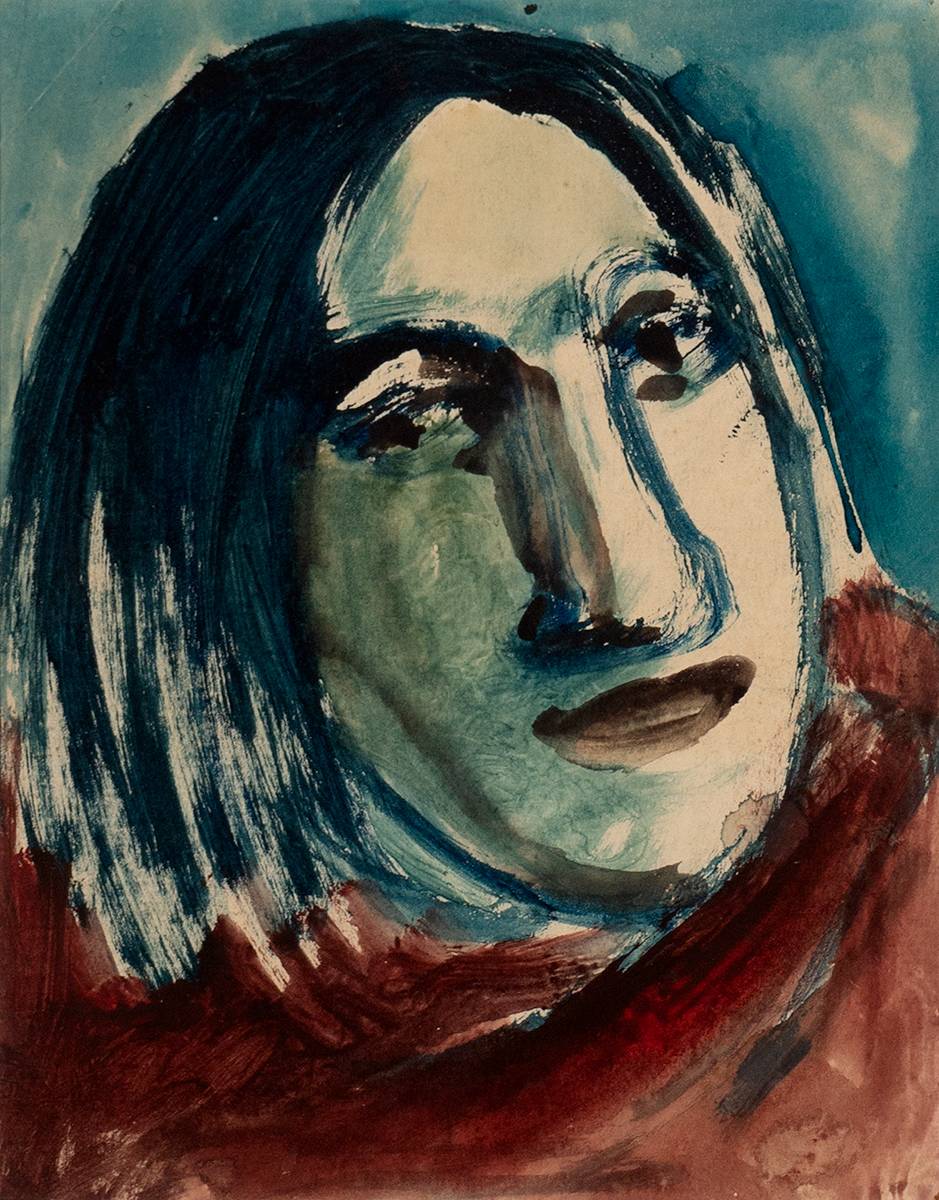

The stations are unique – large tapestries designed by Leslie MacWeeney, an artist who has slipped from our consciousness in Ireland as she moved to the United states while still quite young. There’s a chapter about her in Brian Lalor’s Ink-Stained Hands – she was one of the original founders of the Graphics Studios – and a more recent interview with her here.

This is a nationally important building and an early and striking example of the influence of modern architectural movements on Irish architects. The RTE piece was part of the 100 Buildings of Ireland series. (We visited another one, just up the road – but that’s a post for another day).

In the 100 Buildings piece, Tallon is quoted as taking inspiration from Irish Romanesque architecture.

Irish Romanesque churches… were remarkable for their small size, extremely simple plan, rich and delicate decoration, giving a shrine effect which, at that time, had almost disappeared elsewhere. They were of single-chamber construction, with massive side walls projecting beyond the front and back façades the cross-walls including the façades were left as open as possible and were developed as a series of arched screens.

I am puzzled by this quote and I wonder if Tallon was even referring to this church, which owes nothing to Romanesque architecture. The projections he refers to (known as antae) actually predate the Romanesque style. Take a look at my two-part post on Cormac’s chapel to see if you can figure out why Romanesque architecture has been dragged into the story of this church, as if to somehow Hibernicise a building which belongs, triumphantly, to the International Modern style.

Vatican II and a new generation of Irish architects taking their cues from Europe dragged the Catholic Church I grew up in, into the 20th century. Corpus Christi in Knockanure is at the forefront of that breakthrough design revolution.