There’s a concentration of prehistoric rock art around Castletownshend and I am currently writing a paper about that for the next issue of the Journal of the Skibbereen and District Historical Society. There are seven individual pieces of rock art: as part of the research I recently visited the one stone I hadn’t seen yet. Fortunately, we had the company and assistance of Conor Buckley of Gormú Adventures (been on one of his marvellous walks yet? If not, try this one, or this one or this one.) who, as a native of the area, knows everyone and introduced us to the landowner, the genial Bill O’Driscoll.

The townland is Farrandeligeen – isn’t that a wonderful name? A dealg is a spine or thorn or prickle, and therefore a deilgín is a small one of those. So it can be translated as the Land of the Thorns, which can be blackberries or blackthorns – and this being West Cork, probably both. An old saying is Is beag an dealga dhéanfadh braon – the tiniest thorn can cause big problems. Thorn in a hiking boot, anyone?

The land lived up to its name. Bill took us to where he knew the rock art was, and that’s when we encountered the deligeen bit. Fortunately he had a stout fork with him, and took to hacking and bashing his way through the thorns, while we stood back and offered encouragement. The first place proved unfruitful and he moved a few metres away and soon struck gold. Among the brambles, earth, gorse and general undergrowth there was a hint of something white. This turned out to be a bag filled with stones – the very bag he had put there to remind him that this is where the rock art was – but so many years ago that it had slipped his mind until now.

And so the stone gradually came into view until I could finally get down to clearing it off with my gloves. (I was sorry I hadn’t brought the red socks.) This stone is already in the National Monuments Records as a ‘Cupmarked Stone’ (CO151-013) and is described as having ‘at least ten cupmarks’. Bill told us that his father had said he remembered the stone standing upright – it had fallen to its present position flat on the ground since his father’s time.

For more on what a cupmarked stone is, and how it fits in to the general category of ‘Rock Art’, see my post The Complex Cupmark. For now, quoting from that post:

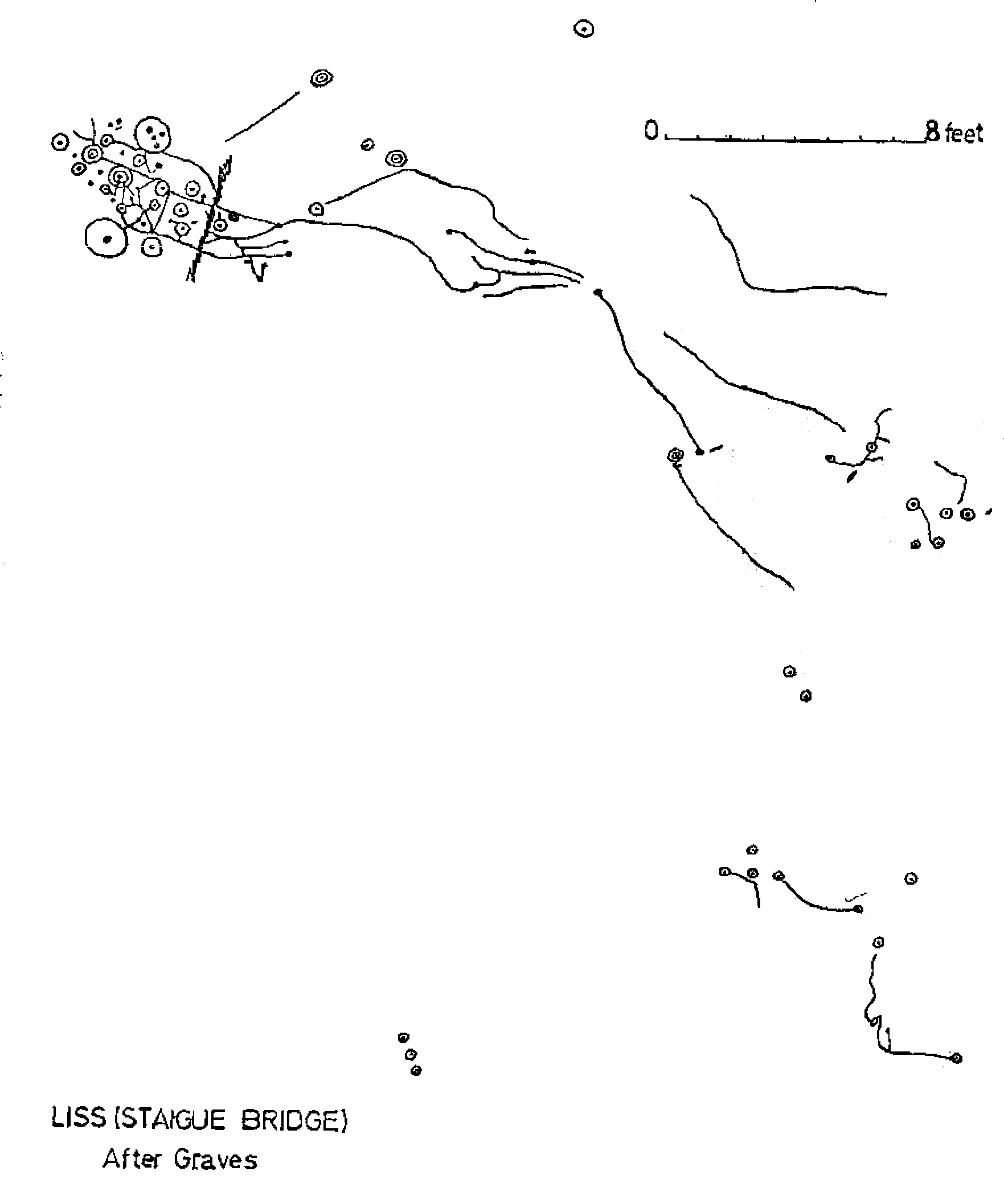

The cupmark is the most basic and numerous element or motif of rock art in Ireland and elsewhere. In the examples labelled rock art in County Cork, they occur with other motifs, principally concentric rings, sometimes with radial grooves, and a variety of curved or straight lines. They can be incorporated within a motif (as in cup-and-ring marks, rosettes, or where enclosed by lines) or they may be scattered, seemingly randomly, over the surface of the rock, between and among the other motifs.

. . . patterns of straight lines, or of rough circles or semi-circles, can be made out in several of the stones we have recorded to date.

Rock art is widespread across the Atlantic coast of Europe and is believed to date from the Neolithic, about 5,000 years ago. The cupmark as a motif, however, continued well into the Bronze Age, since we find it on wedge tombs and boulder burials. We do not know what the significance of the cupmark is, but it must have held a special meaning to the carvers since it persisted over time and space.

We got the rock cleared enough to identify the cupmarks and I put a button in each one to make sure it showed up – sorry, those are not gold coins. Some of the cupmarks are tiny. You can look at the cupmarks as a random scatter, or as in the quote above, you can see two groups, in which a cupmark is surrounded by a semicircle of four others.

It was hard to get the rock clean enough to see detail so I decided to carry out a photogrammetric survey, the object of which is to end up with a 3D image from 2D photographs. That involves taking LOTS of photos (in this case, 100) of the stone, working my way systematically across the surface of the stone at three different levels, keeping the camera settings consistent.

Conor had his drone with him – a new experience for us! He took photos and videos of the stone in its general location, capturing me doing the photogrammetry and also a good indication of the amount of undergrowth that had to be cleared out of the way before the rock came into view. (Thank you, Bill!)

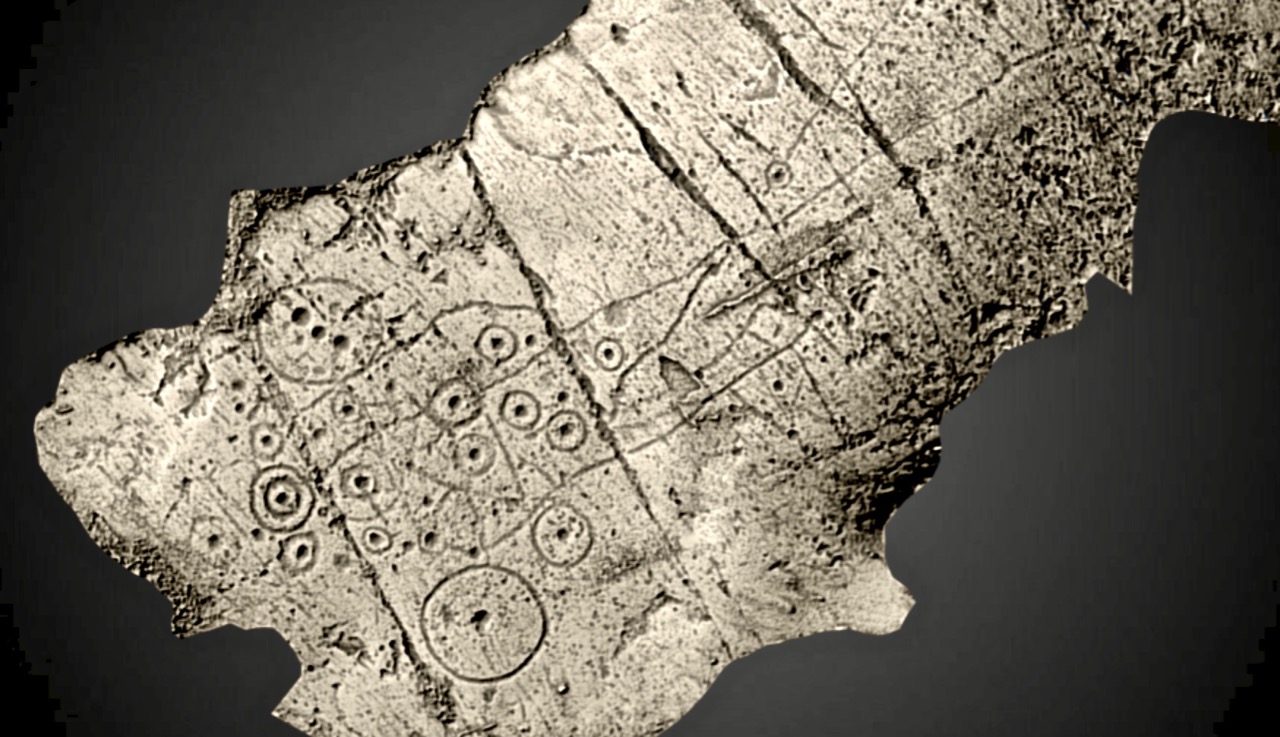

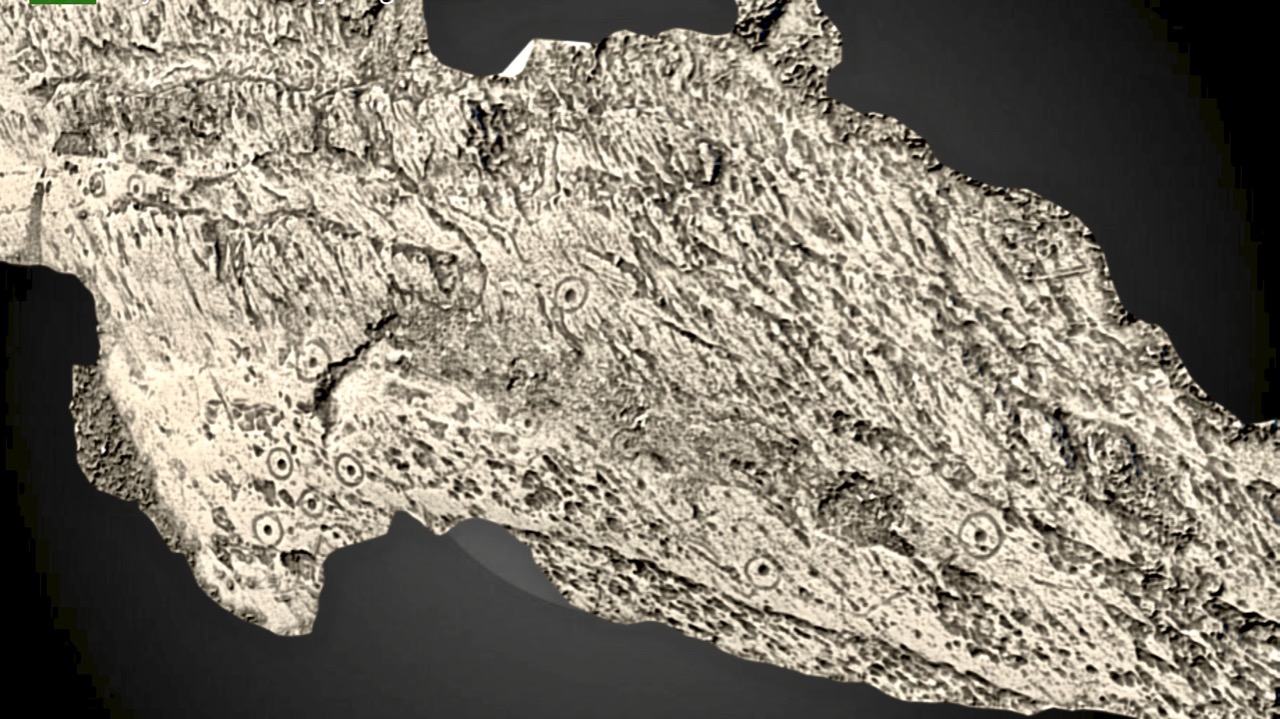

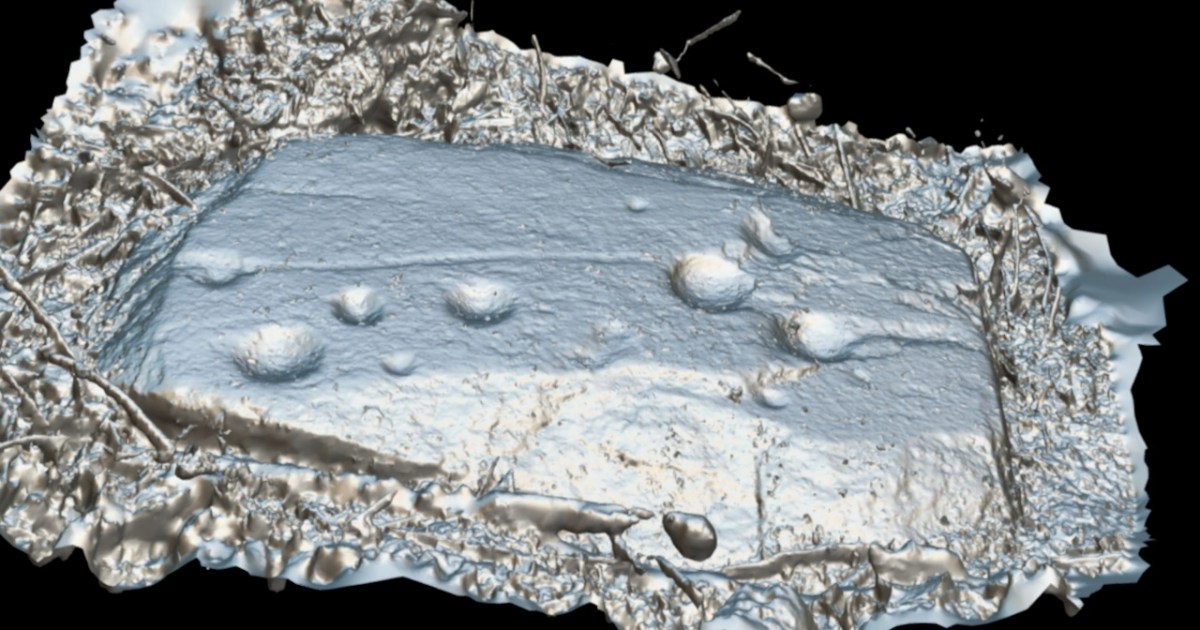

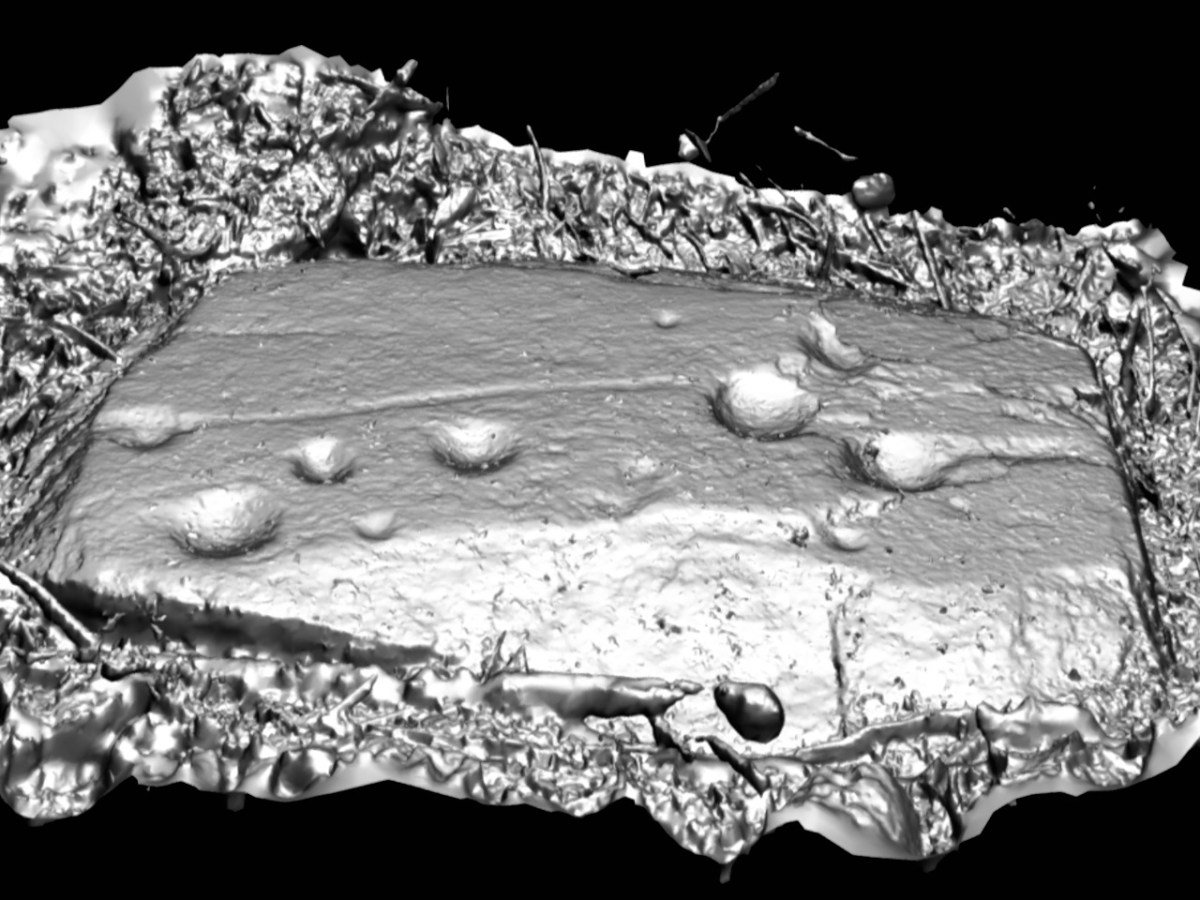

I sent the photographs off to UCC, to the Department of Archaeology, where Nick Hogan generously processed them for me, using the Department’s specialised software. The results are fascinating!

First of all, it looks like there are more than just cupmarks on this rock. A long line stretches from the far left (in this image) cupmark to the right hand grouping. There is a hint of a circle around the bottom left cupmark. The three large cupmarks in the right grouping appear to be conjoined, and there is a line from from the far right cupmark to the end of the stone.

You can view the render in what is called Matcap, which creates it in a metallic view (above and below). On a grey day with no shadows, and still lots of mud on the stone, none of this was obvious to the naked eye. There is a possibility that these new elements, rather than being carved, are natural contours in the rock itself. We haven’t had time yet to go back and check this out more carefully, but we will have to do so – and update this post! If indeed the lines turn out to be carved, that fact will elevate the rock from a Cupmarked Stone to Rock Art. Watch this space.

If you’d like to see the 3D render for yourself and have fun turning it this way and that, you can click here. Let me know if you spot anything else! It was good to be out in the field again after a long winter of cold wet weather. It was great to have Conor and his drone along and to meet Bill, who is committed to keeping safe this precious part of our heritage.