The three books I am recommending today are ideal for the person in your life who loves West Cork and/or fine art. All three are by West Cork men and all three are self-published. Even though self-publishing is increasingly common, distribution is often monopolised by the large publishing houses, so I am delighted to have the opportunity to bring these three to your attention.

Let’s start with Dennis Horgan’s latest – The Coast of Cork, A View from Above. Dennis has been incredibly generous in allowing us to use his photographs in the past, but we have never reviewed one of his books before. In the age of the drone, it’s easy to forget that only an aerial photograph can capture the most expansive views – a whole island, for example, or the sudden rise of a humpback whale, or a seascape feature that is too far from land to capture any other way.

Dennis is the real deal. Leaning out of a plane flying at 150 miles an hour, kept safe only by a seat belt – it’s not for cowards. Add to this his mastery of photographic techniques necessitated by speed, varying light, changing focal lengths, wind and cloud and here you have a virtuoso photographer working at the height of his powers.

And he’s a Cork man through and through – his knowledge of and love for our coast is obvious. He knows these places on the ground and so he knows exactly what he wants to show us, and how he wants us to see it. You can find the book here, along with more of Dennis’s magnificent panoramas.

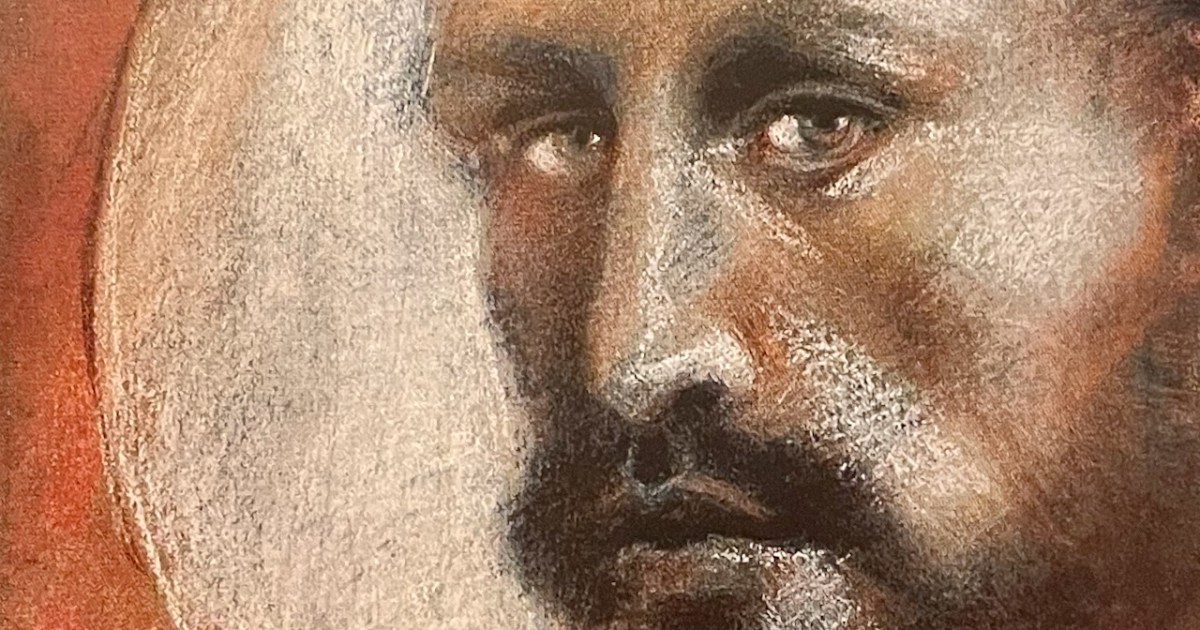

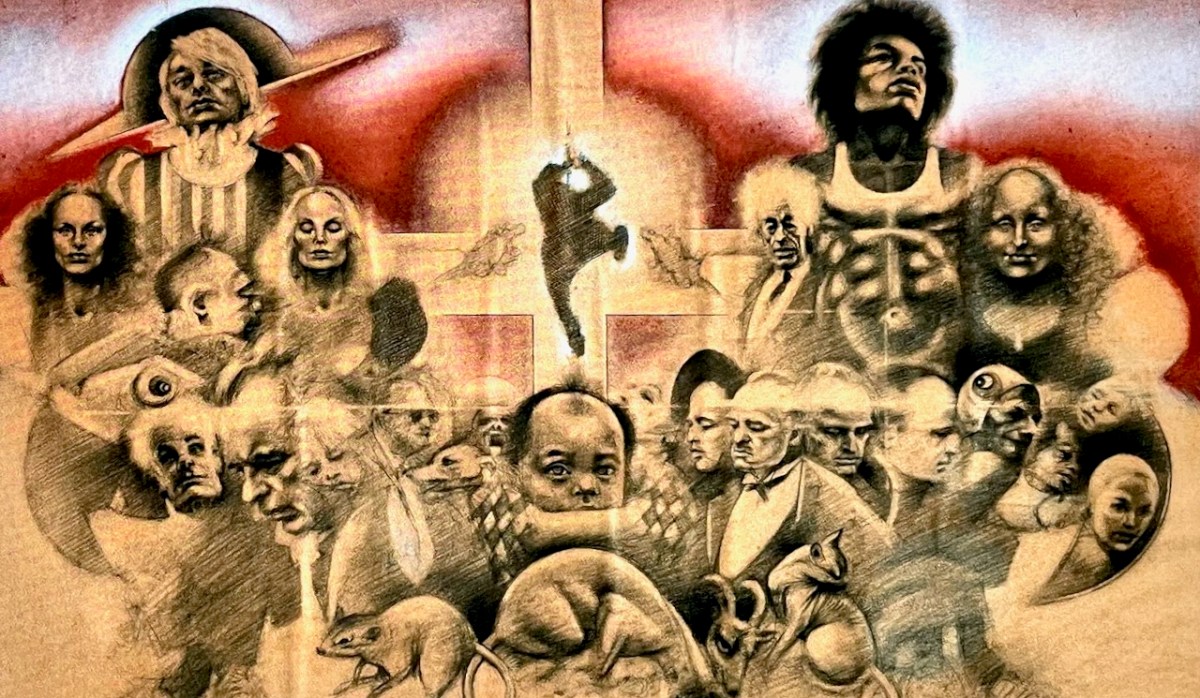

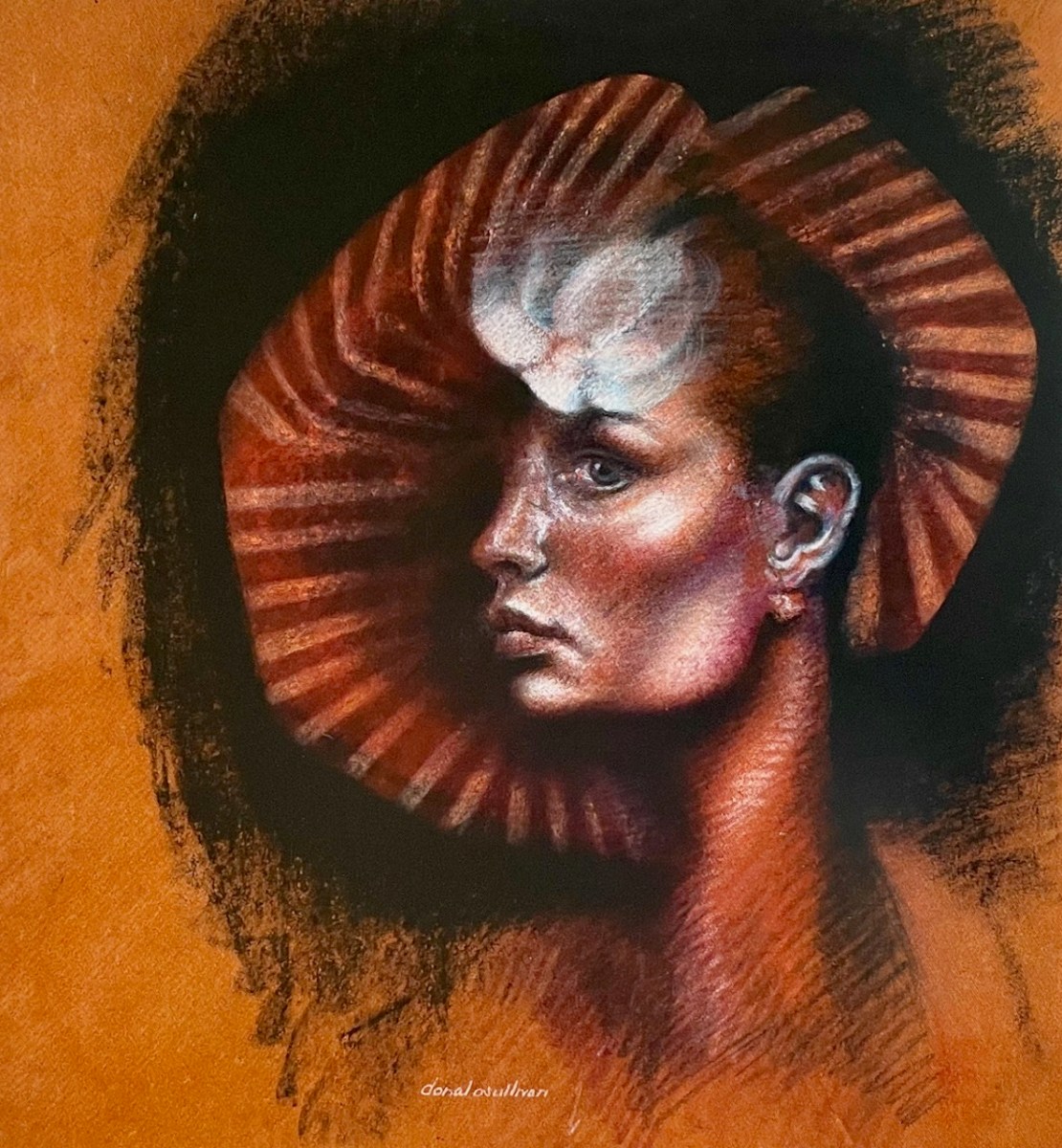

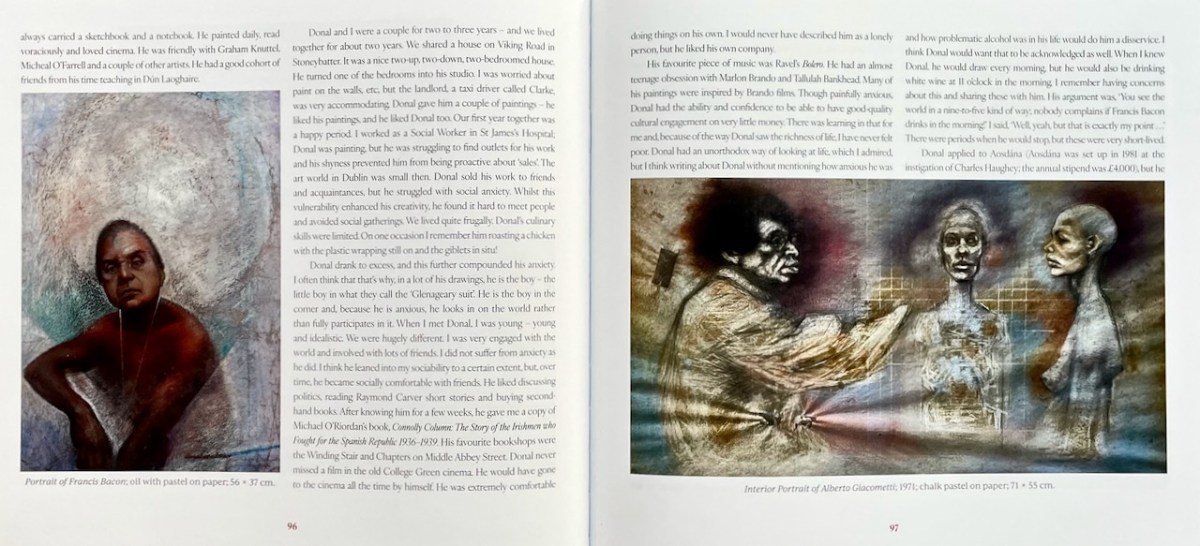

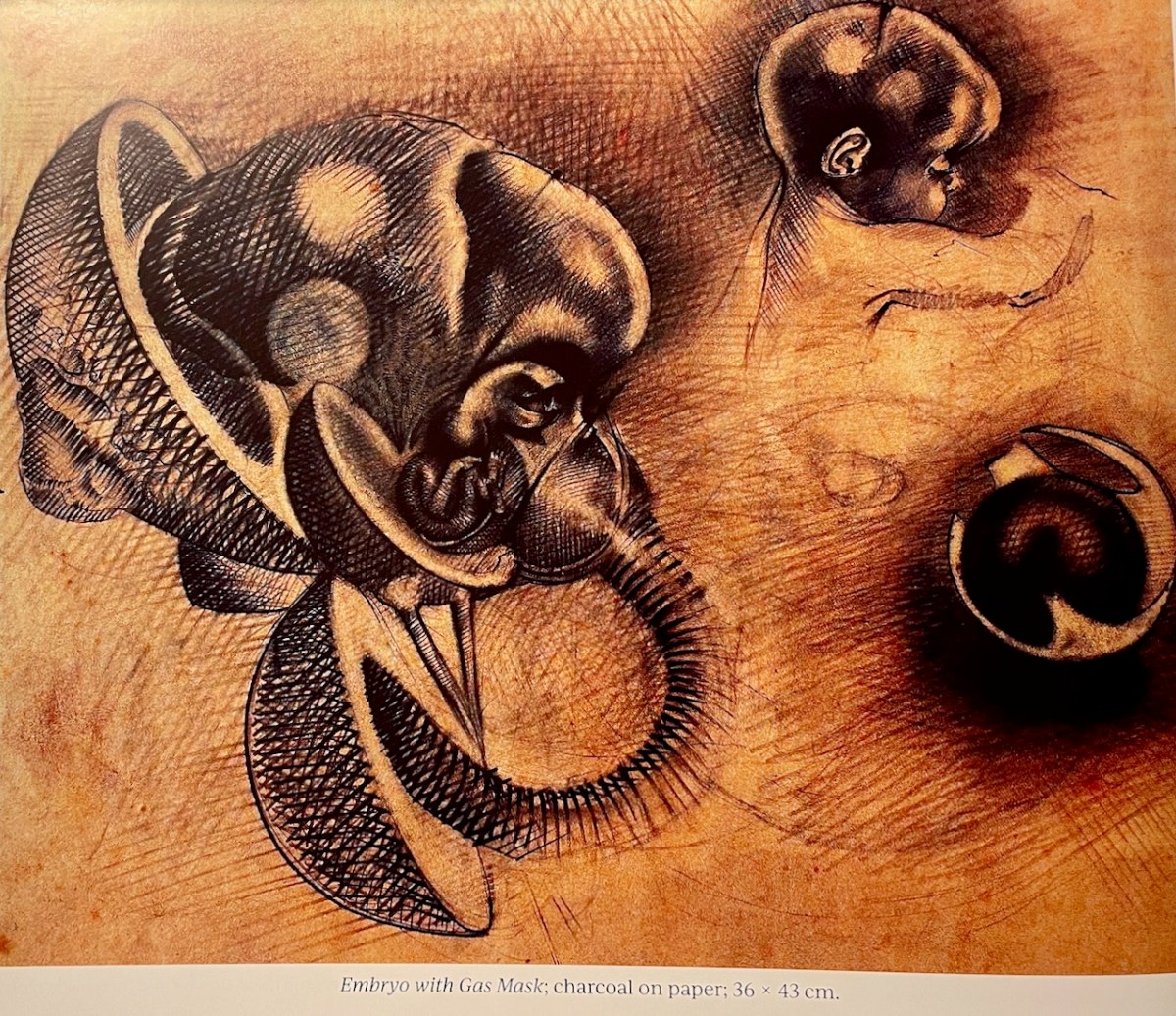

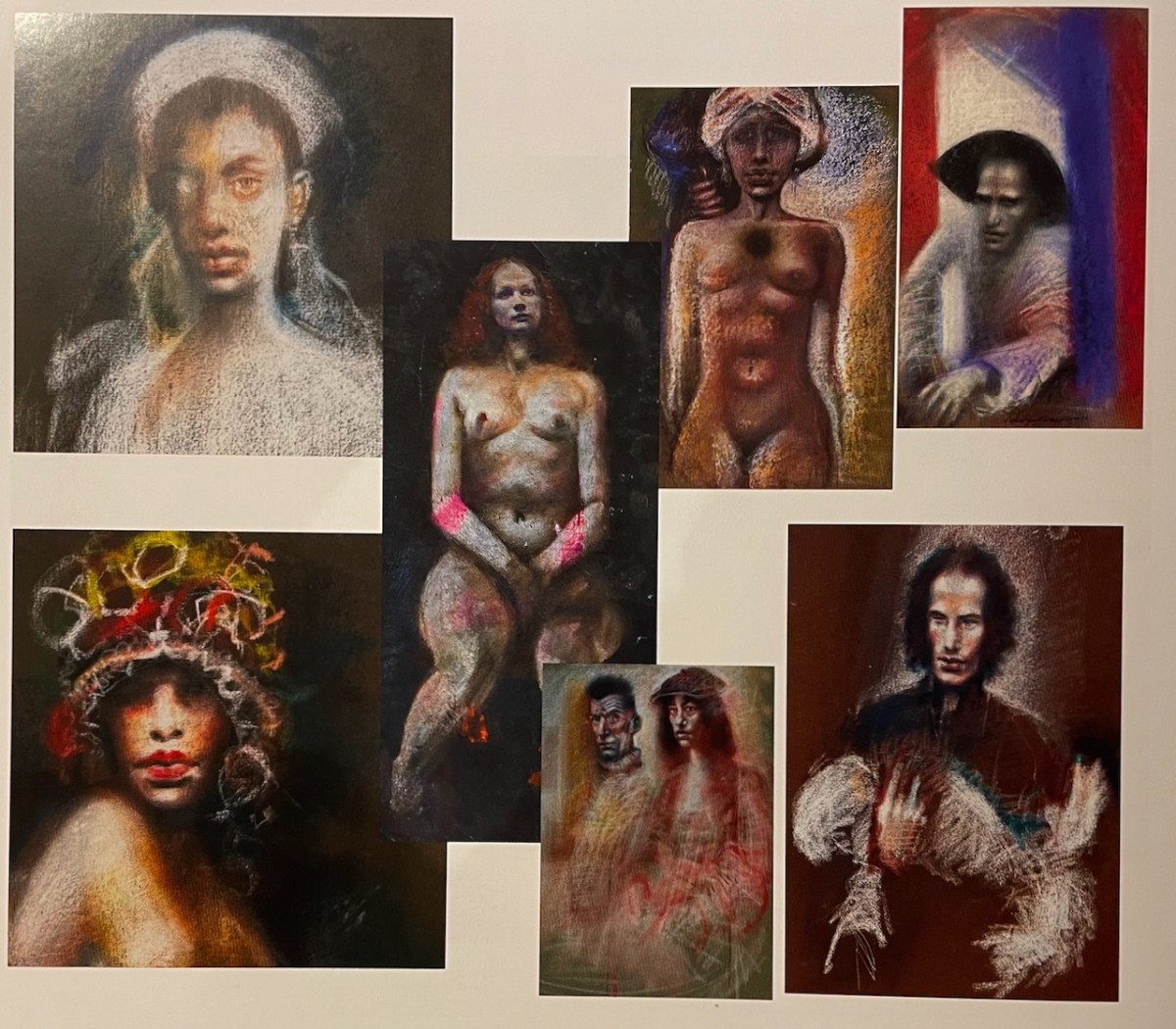

Our second book, Donal O’Sullivan: An Artist Remembered, is a revelation – why has nobody heard of this man? In jaw-dropping image after image, Paul Finucane and Brendan Lyons reveal the forgotten genius of O’Sullivan, whose preferred media, pastels and pencil, glow out from these pages.

We learn about his students activism – he was a leader in reforming the old-fashioned and under-resourced College of Art, still languishing in basement rooms in Kildare street in the late 60s, with a curriculum dictated by civil servants (no life drawing, use those plaster casts!). Later, he was a beloved teacher in Dun Laoghaire, a friend and mentor to many.

There are several descriptions of his chaotic studio. It sounded much like that of one of his inspirations, Francis Bacon, now reproduced in the Hugh Lane Gallery. He died by suicide when he was only 46, mourned by the family who loved and supported him through his later addiction battles, and those in the art world who remembered him as gentle, kind, encouraging, and fiercely individual.

A piece in the Irish Times says, he had gone against the expressionism that was fashionable in Irish art circles at the time, trading instead in powerful, elegant and melancholy figurative art that often discomfited its viewers. That same piece has a video that shows many, many of his works, carefully preserved by his sister, Marie. There are many self-portraits – my lead image is a detail from one. And many nudes, despite the best efforts of those 1960s civil servants.

Finucane and Lyons, who also mounted a retrospective exhibition in September at Union Hall’s respected Cnoc Building Community Arts Centre, deserve all our thanks for rescuing this extraordinary artist from obscurity. You can purchase your own copy here.

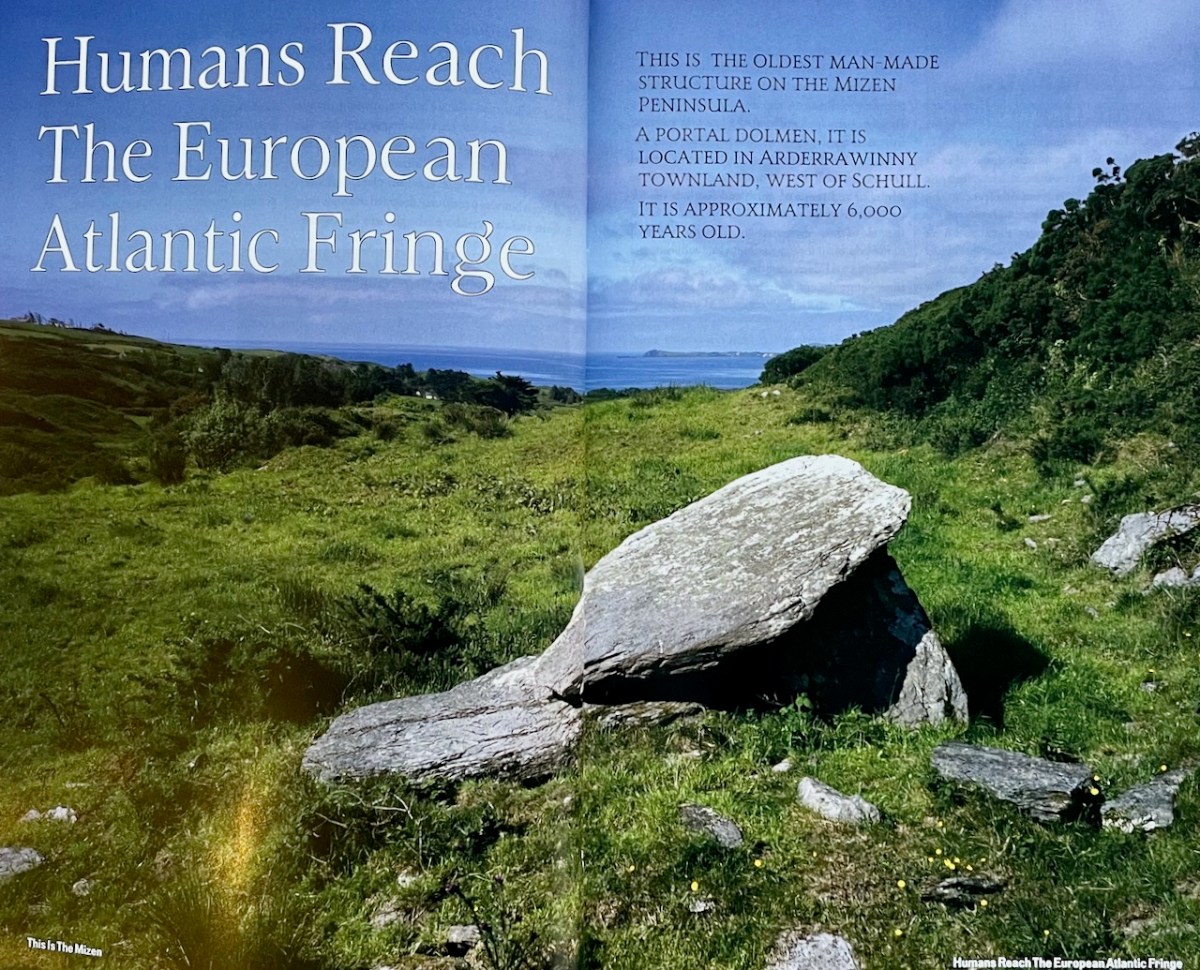

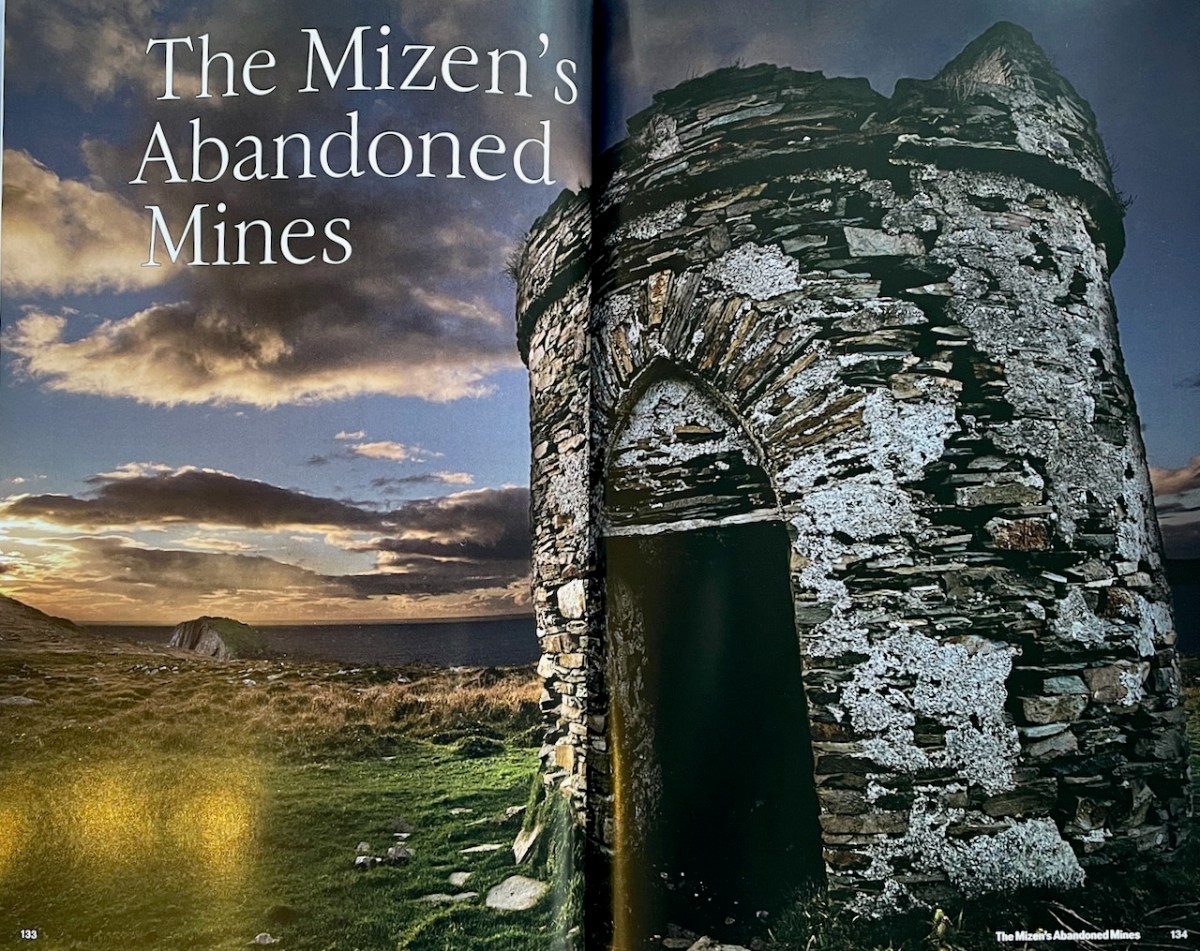

Finally, a book that, according to its writer, has been 18 years in the making, deals with a topic dear to my own heart. This Is The Mizen, by John D’Alton, delves into the history and prehistory of the Mizen Peninsula, copiously illustrated by John’s own photographs as well as historical images.

John, a former journalist and professional photographer, loves a moody landscape and his photographs often highlight a building or landscape lit by a setting sun. He has produced two previous books about West Cork (see here for example), using his own images.

But this is not primarily a picture book, but rather an extended essay on the history of the Mizen Peninsula, from the earliest times. Regular readers might recognise the partial fort above – I wrote about it here and here. Don’t expect a turgid academic treatise: John has done his homework, and combines that with his own trenchant opinions, and a take-no-prisoners approach, to provide a highly readable account of this area. The book is available at local bookstores, such as the lovely Worm Books, or at https://www.buythebook.ie/product/this-is-the-mizen/

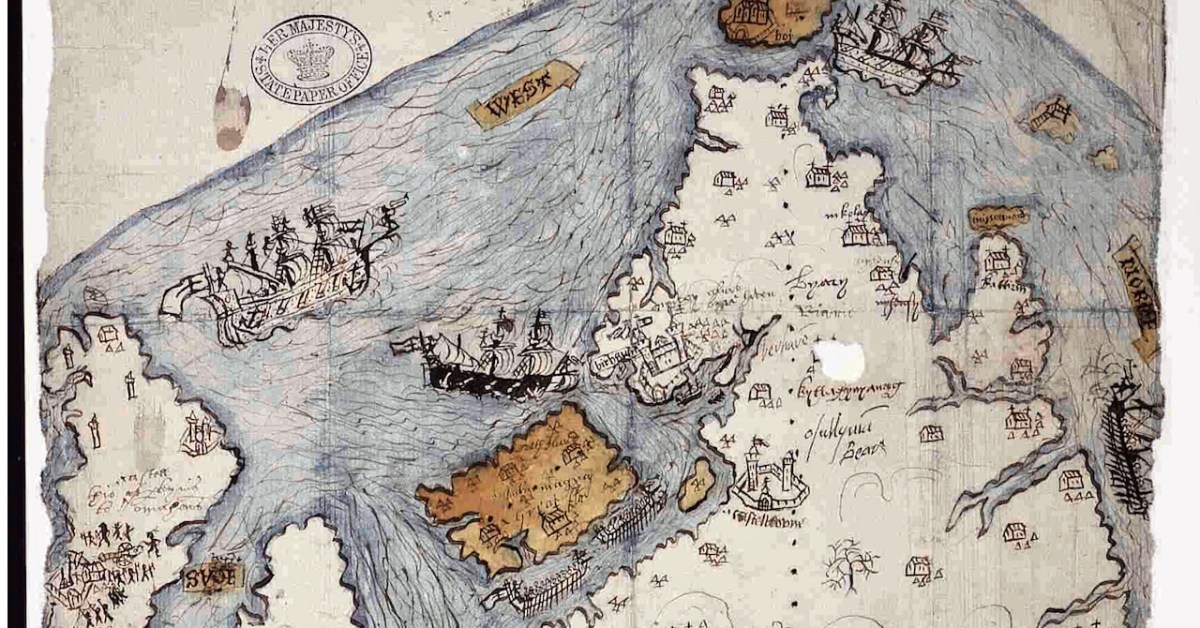

Above, Whiddy Island from Dennis Horgan’s The Coast of Cork