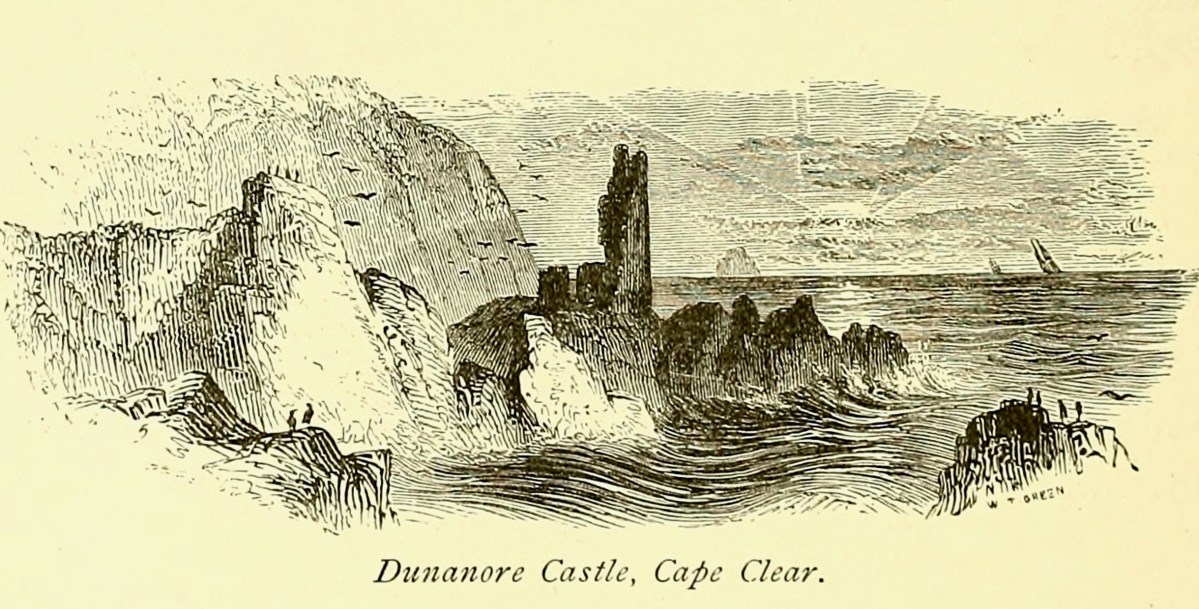

I have been gifted with a marvellous set of photographs of Dunanore, or Dún an Óir – an O’Driscoll Castle on Cape Clear. The gift came from one of our readers, Tash, and I am very grateful indeed. Regular readers know that I like to use my own photos, and I do have some that I took from the sea (like the one below) but I have none of Dún an Óir from the land, let alone from the castle itself!

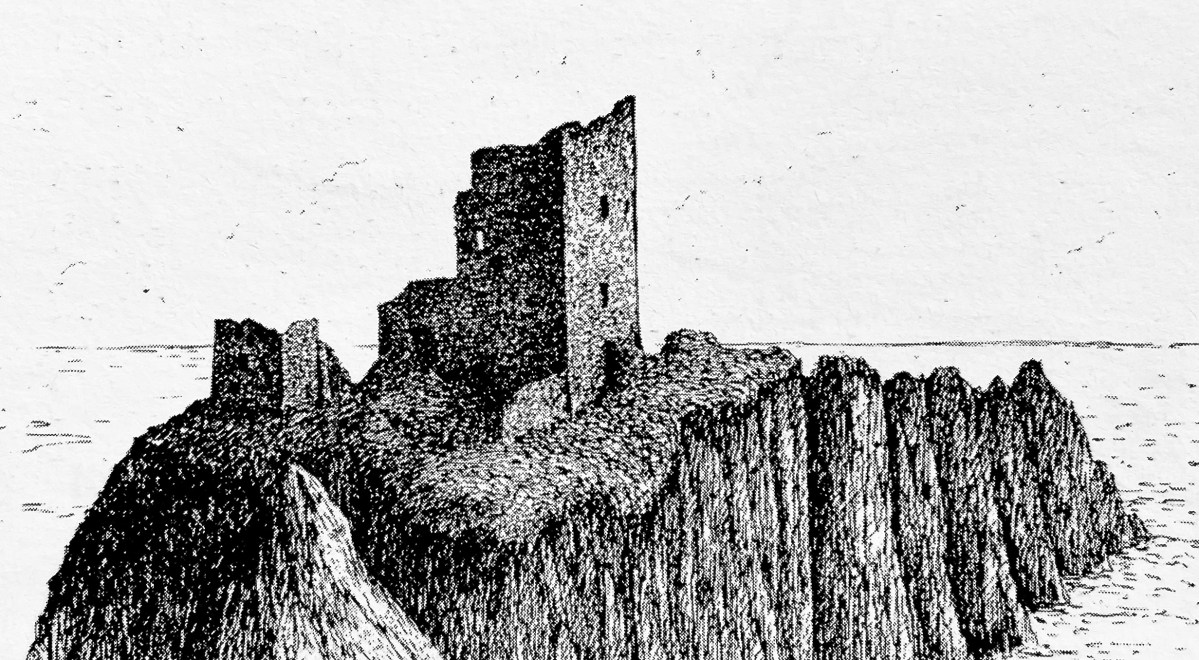

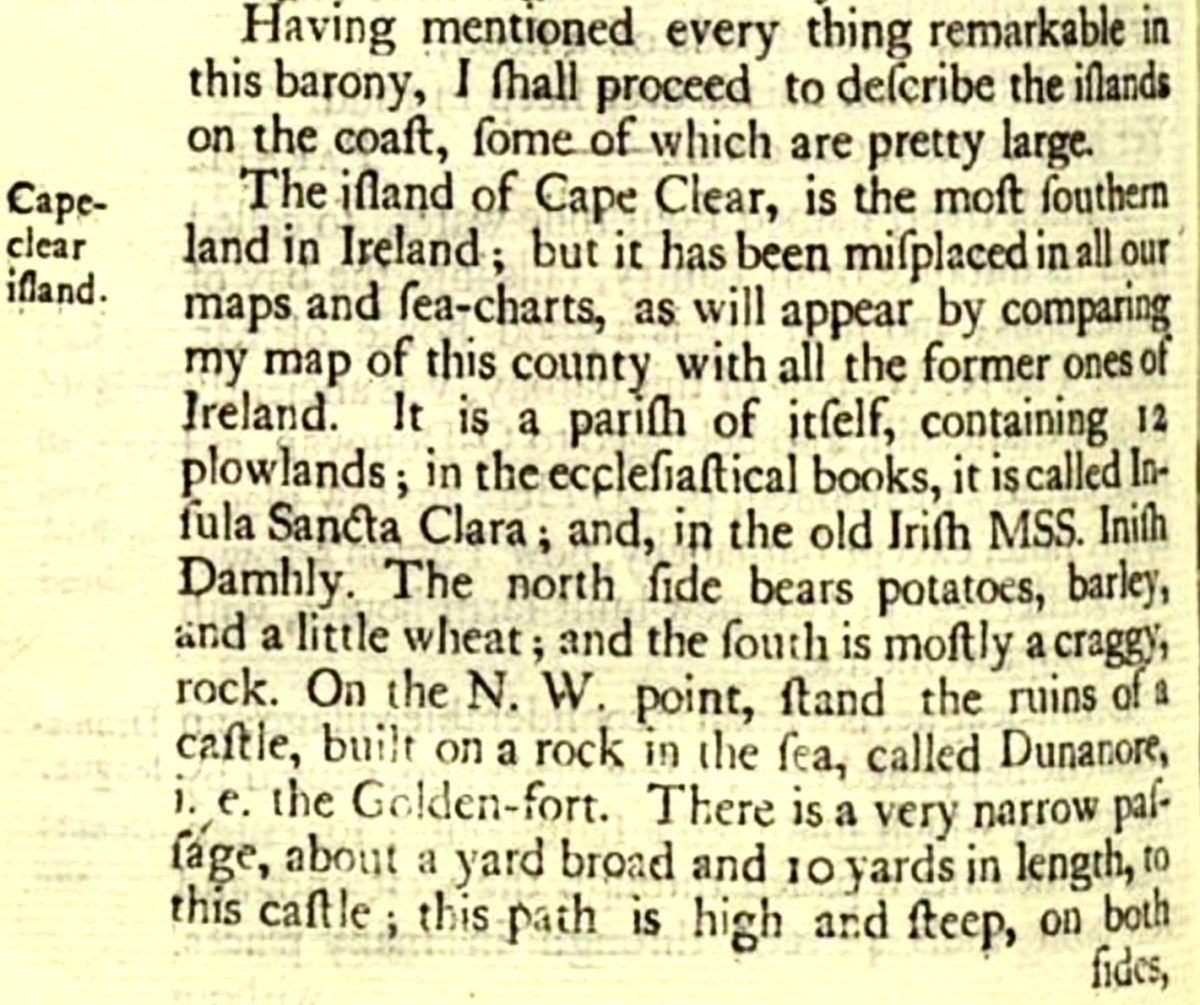

And that’s because, as you can see from the drawing by Jack Roberts at the top of this post, this castle is situated in a very perilous location, on the edge of a cliff, on a small island, essentially, making access a hazardous scramble up from a rocky beach. It was once connected to the rest of Cape Clear by a narrow causeway but this has long collapsed. It was still there in the 1770s when Charles Smith visited. In his The Ancient and Present State of the city of Cork Vol 1, he wrote:

And this brings us to the name – Dún an Óir. It means, of course, Fort of Gold, and some of the old legends about this place talk about the name coming from stories of buried treasure. But in fact, this has been the name of this fort since the first maps of this area were made in the fifteen hundreds and it speaks to the wealth of the O’Driscoll clan who built it. Remember, their other stronghold, now called Baltimore, was Dún na Séad, or Fort of Jewels (on at least one map given as Castle of Perles). On Sherkin, their castle was Dúnalong – or the Fort of the Ships – that’s it as it is now, below.

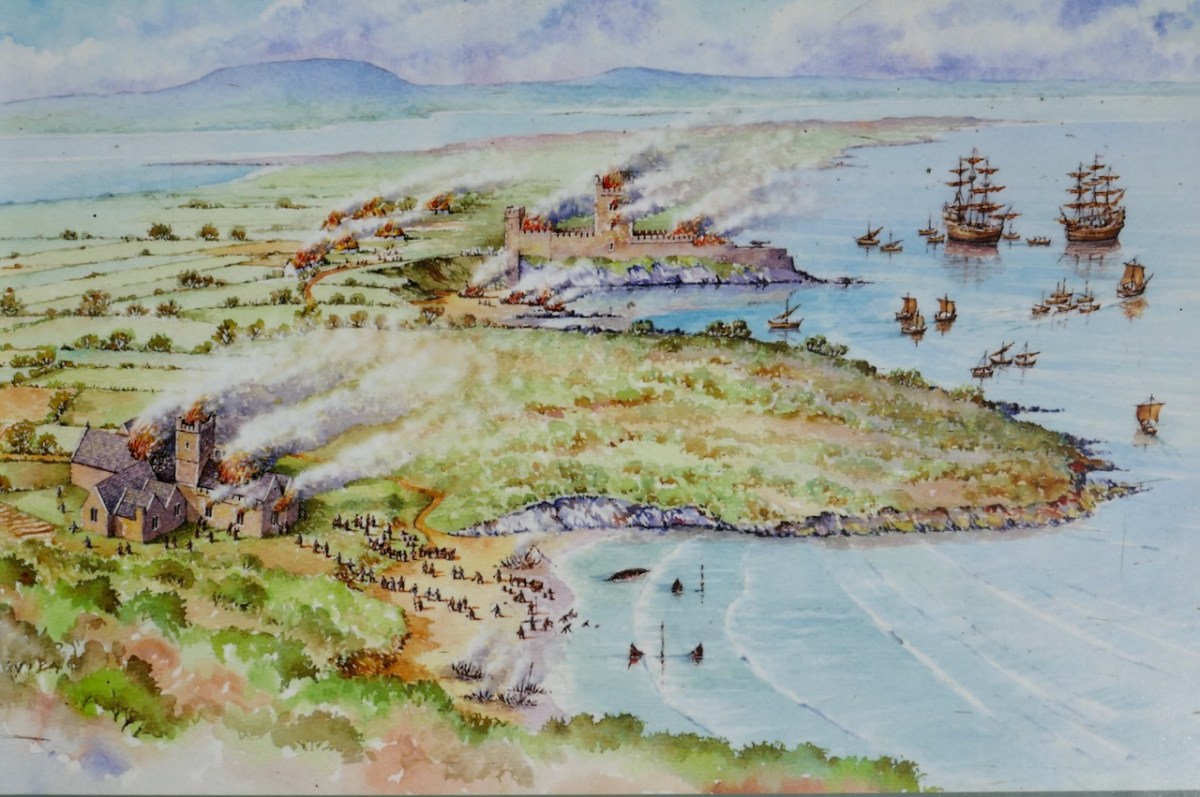

There are many accounts of their fleets of ships, and the battles they waged against the Waterfordmen in which they came out the worst for wear when Dunalong was attacked. The scene below, from an information sign on Sherkin, shows the Battle of the Wine Barrels, 1537, with both Dunalong and the Friary on Sherkin in flames

Dún means ‘fort’ but seems to be especially applied to promontory forts in the southwest. Before the castle was built, therefore, it is likely that the O’Driscolls fortified the headland, which may date well back to the Early Medieval period (400-1200) or even to the Iron Age (500BC to 400AD, or 500BCE to 400BC for those who prefer the secular version). The Illustration below is taken with permission from Dún an Óir Castle: an uncertain future, by Dr Sarah Kerr, and shows the present state of the castle, marooned on what was once a promontory connected to the Island.

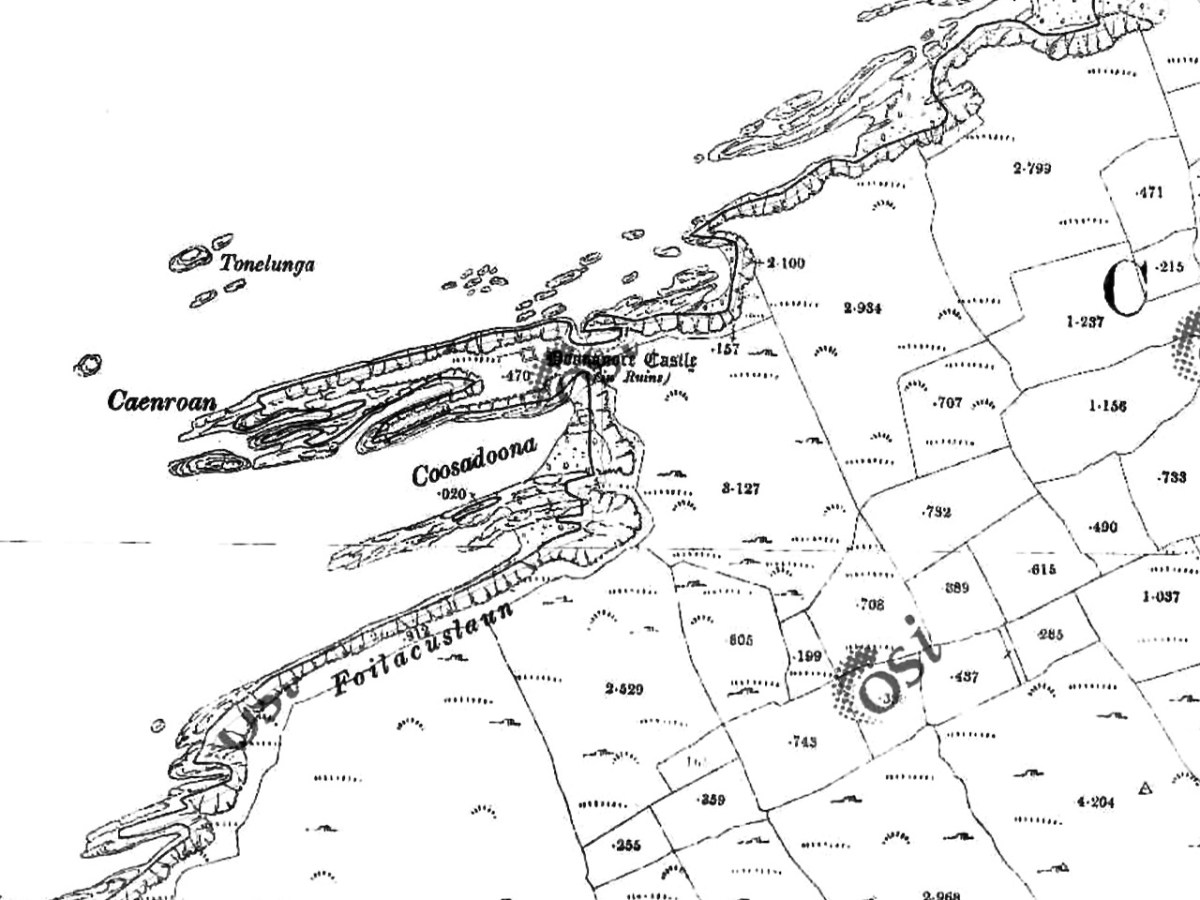

Our Promontory Fort man is Thomas Westropp (see here and here), and he wrote about Dún an Óir in his 1914-16 paper for the Royal Irish Academy, Fortified Headlands and Castles in Western County Cork. Part I. From Cape Clear to Dunmanus Bay. He visited the site, but like many a good explorer before and after him, did not venture out onto the promontory, but satisfied himself with what he could see from the high ground above it. That included the promontory and ruined castle, the rather ominously named Tonelunga (The sea-bed of the Ships), the end of the promontory called Caenroan (quay of the Seals), the inlet between the promontory and the cliffs, Coosadoona (the Little Harbour of the Fort) and the high cliffs behind the fort, Foilacuslaun (Cliffs of the Castle). All of these are marked on the 19th century twenty-five inch map.

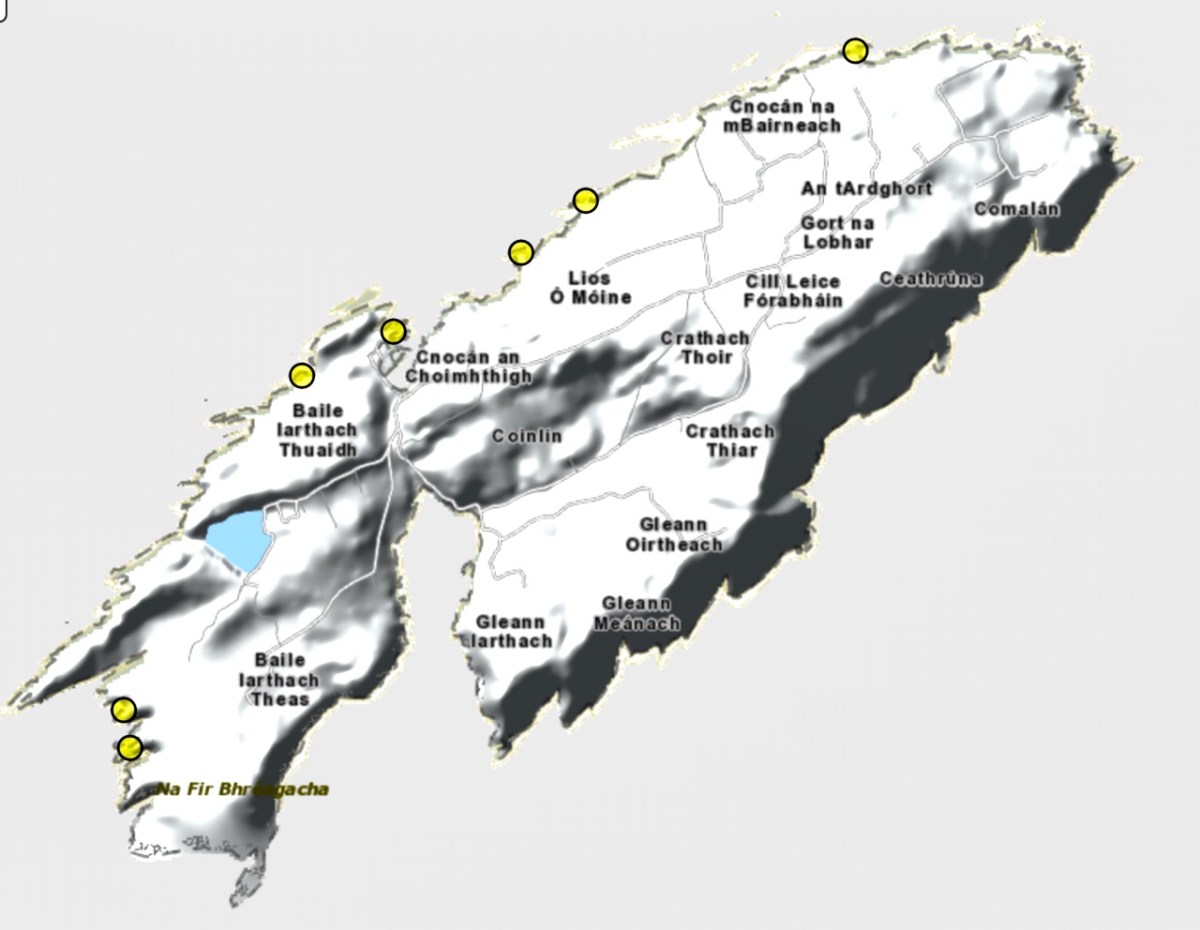

Westropp writes about Dún an Óir as one of three Promontory forts on Cape Clear Island, although in fact there are more than that, as identified by the National Monuments Record – each yellow dot below is one.

Here’s one of them (below), Lios Ó Móine (the Fort of the Meadow – lios is usually used to designate an earthen ring fort): the description and then the photo are by National Monuments Service (NMS). In the photo you can see the narrow neck of land leading out to the promontory. This is likely what the spit leading out to Dún an Óir may have looked like.

Description: In rough pasture, at the foot of a steep N-facing slope on Stuckaunfoilnabena, a headland on the NW coast of Clear Island. A narrow eroding neck of land (Wth 3m; L 15m) leads to the roughly anvil-shaped headland. Across this neck of land are the remains of three earthen banks and the shallow remains of three fosses. Further examination of the remains was not possible for safety reasons.

Curiously, the NMS does NOT identify Dún an Óir as a promontory fort – here is what it says:

Description: The location of the tower house ‘Doonanore Castle’ (CO153-015002-) on a promontory, on the NW shore of Clear Island, suggested that it may have been built on the site of a promontory fort. However, there are no visible surface traces of an earlier defences across the promontory. The promontory is now isolated at high tide but was connected to mainland by causeway until 1831.

However, it has this to say about the earthwork identified on the high ground:

In pasture, on a steep N-facing slope to the E of the tower house known as Doonanore Castle . . . An earthen bank . . .extends upslope in a S to SW direction from a modern E-W field boundary wall on the cliff-top at N and ends at a large outcropping rock on the edge of another cliff. This bank appears to have formed part of the defences on the land approach to the castle from the E. The bank has three contiguous linear stretches [and] there is an entrance near the N end. There is a possible hut site near the centre of the enclosed area. The short promontory on which Doonanore Castle stands is a possible coastal promontory fort.

So, as you can see, although the NMS declines to label it a promontory fort because there are no longer any signs of banks or walls, it does concede that it is possible. It also extends the defences of that fort to the higher ground above it.

Back to Westropp – He quotes:

the poem of O Huidhrin, before 1418, tells how “0 hEidersceoil assumed possession of the Harbour of Cler.” It was of some importance to the foreign traders in wine and spices, and so figures in all the early portolan maps. Angelino Dulcert, in 1339, calls it Cap de Clar ; the subsequent portolans, Cauo de Clara, 1375 and 1426 ; Clarros, 1436 ; C. d’Clara or Claro, 1450 and 1552, and, to give no more, Cauo de Chlaram, in 1490. The 0 Driscolls’ Castle probably dates between 1450 and the last date. It was probably on an earlier headland fort, as it is called Dunanore. In 1602 it surrendered without resistance to the English, who burned it.

Westropp goes on to say

Dr. O’Donovan, in his ” Sketches of Carbery,” gives a few notes on the later history. He says there was a garrison at the Castle in Queen Anne’s time, and mentions the huge iron ring-bolt, set in the rock, to which the O Driscolls formerly moored their galleys in the creek. The last is improbable, even to impossibility: no one could moor galleys in the dangerous wave-trap, open to the most stormy and unsheltered points. The islanders regard the ruin as haunted, and tell of the singing of ships’ crews in its vaults. One “Croohoor” (Conor) O’Careavaun (Heremon’s grandson) lived as a hermit there in the eighteenth century. Another legend tells how, in 1798, the inhabitants painted the Farbreag Rocks and pillars so as to resemble soldiers in uniform to keep away the French ! If any truth underlies this, it is probably based on the idle act of some revenue or other officers, in the endless leisure of their island station.

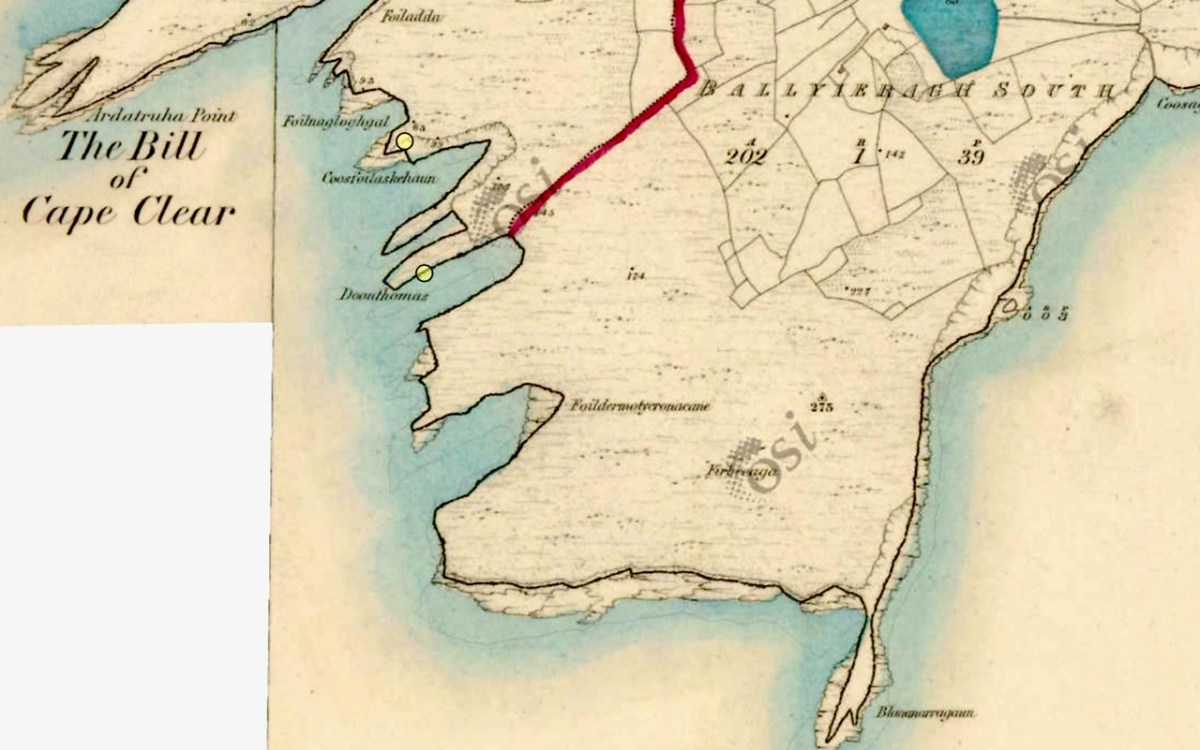

In the map above, of the southwest end of the Island, you can just make out the name Firbreaga, almost covered by the O of OSI. Fir Bréaga means The Lying Men, an apt translation given Westropp’s story. No doubt the name is older than 1798, and may refer to the cliffs at that end seeming to be less dangerous from the sea than they actually were. Note also the two yellow dots for two more promontory forts- Doonthomas (Thomas’s Fort) and Coosfoilaskehaun (the Small Harbour of the Knife-Edge Cliff).

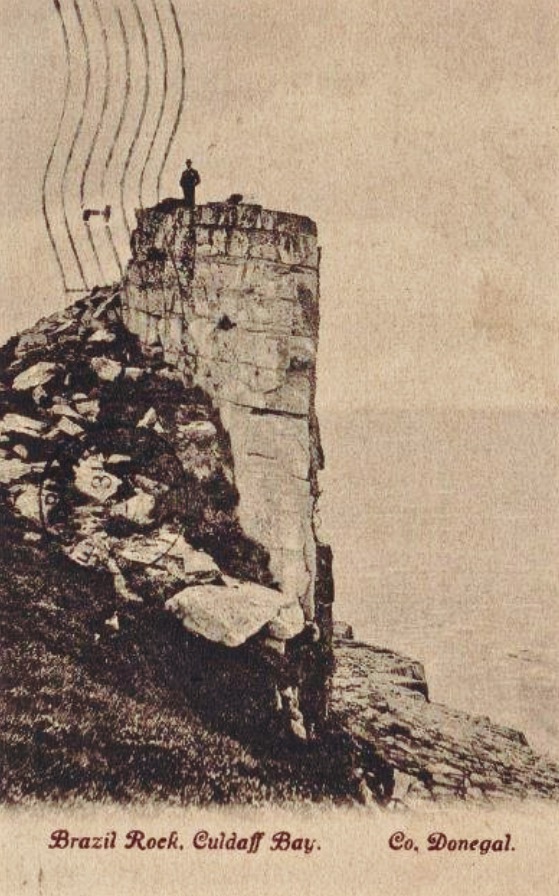

Westropp’s description of the promontory upon which Dun an Óir sits is poetic:

The path runs up a very slight ledge, flaking away and high above the creek, along the face of a cliff of polished silvery slate. The low neck joined it to the mainland, and the nearly perpendicular strata make the dock-like creek of Coosadoona, fort-cove, to the south Beside this cove, opposite to the castle, an enormous precipice rises high above the tower top. In the other direction is a noble view across the wide, porpoise-haunted bay, and its low islands to the blue, many-channelled Mount Gabriel, and on to Mizen Head.

In fact, very little is known about the history of Dún an Óir before the Battle of Kinsale in 1601. We can deduce from its strategic location that the O’Driscolls used it to keep an eye on every ship that sailed in and out of Roaringwater Bay, to exact fishing dues before the rival O’Mahonys could get to the incoming vessels, to curb the power of those O’Mahonys, and to establish their dominance over the land of Cape Clear Island. (See this post for more on the map above.) Because the castle would have been rendered, probably in some shade of white or near-white, it would have been visible from all around Roaringwater Bay, and have represented a potent statement of supremacy.

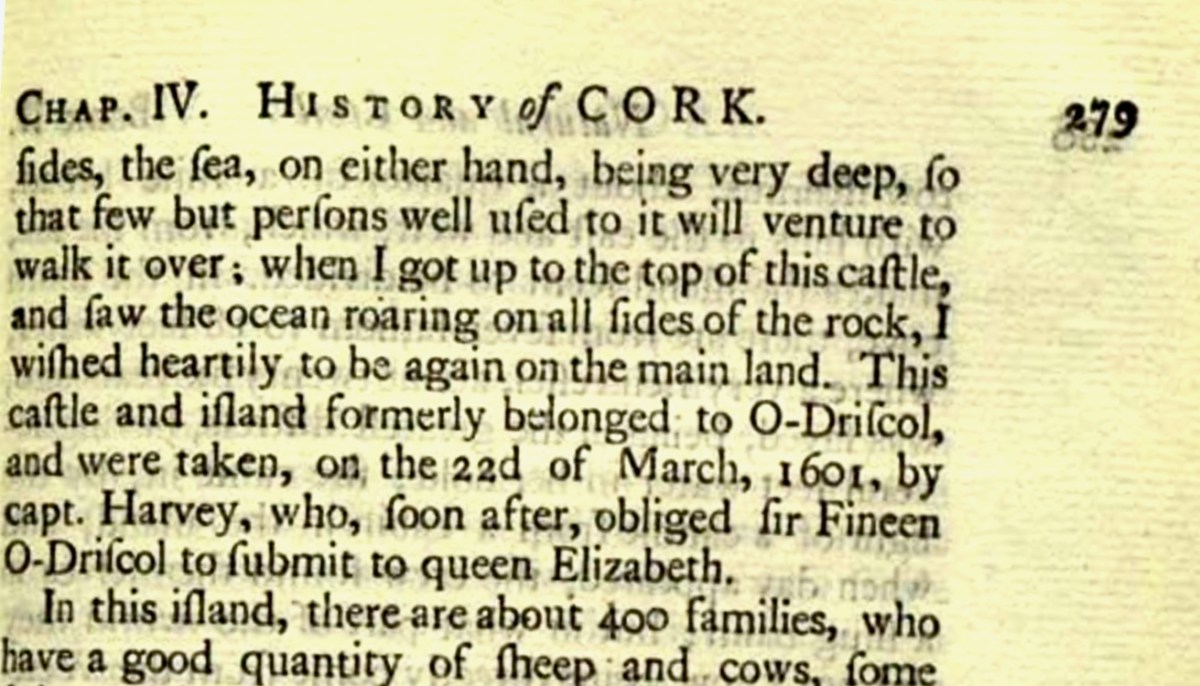

After the Battle of Kinsale the Castle was seized by Captain Harvey, as described in Pacata Hibernia:

‘While these things were on doing, Captain Roger Harvy sent a party of men to Cape Clear, the castle whereof being guarded by Captain Tirrell’s men, which they could not gain, but they pillaged the island and brought thence three boats; and the second day following the rebels not liking the neighbourhood of the English, quitted the castle, wherein Captain Harvy placed a guard. At this time Sir Finnin O’Driscoll came to Captain Harvy and submitted himself.’

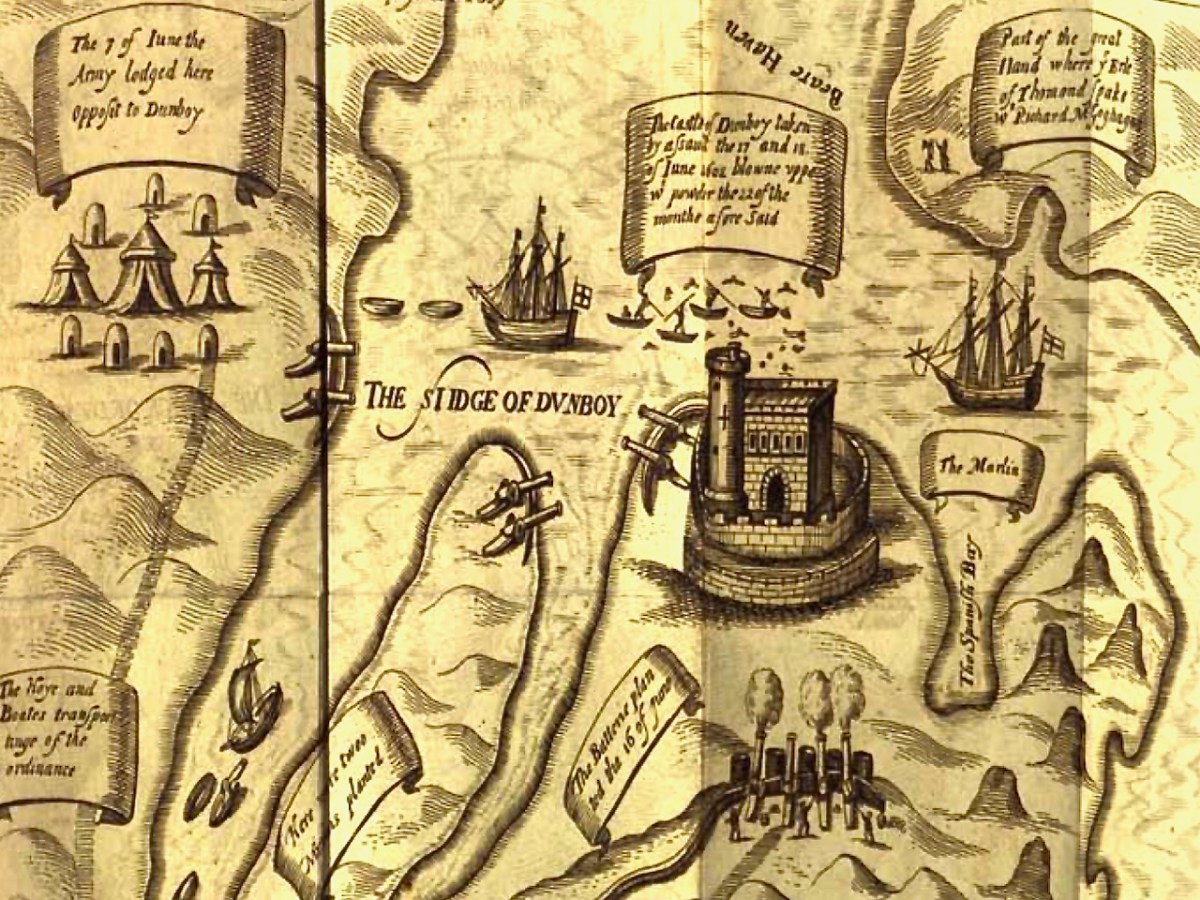

This illustration, from Pacata Hibernia, is of the siege of Dunboy Castle, the stronghold of O’Sullivan Beare, on Beara Peninsula. The destruction of Dún an Óir is described by James Burke in his article Cape Clear Island in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society Journal of 1908. Rather than Harvey simply taking over the castle, Burke relates the following:

Its central arch and the steps leading to its upper portion remain; but the huge pieces of its eastern wall now lying about show how severely it has suffered from the havoc of war. This wholesale destruction occurred when Dunanore Castle, together with the island, was captured on the 22nd of March, 1601, by Captain Roger Harvey, following on the defeat of the Spaniards at Kinsale. By means of the artillery he planted on the high ground adjoining it, he battered down the eastern wall and compelled the garrison to surrender, for which and other services (as Dr Donovan writes in his “Sketches of Carbery”) he was granted at the time a commission by Lord Deputy Mountjoy as Governor of Carbery.

It is far more likely that the ruined state of the castle is a result of the natural passage of time than the ‘havoc of war.’ For one thing, it would have been a monumental task to deploy artillery overland on Cape Clear. Any cannon fire would have come more naturally from the English warships we know were in use during this period and therefore, the damage would have been to the seaward side of the castle – but this side is actually intact.

A romantic view of the ruins of Dún an Óir above, by W Willes.* Next week we will look at what is left of the castle and what we can tell from that. I’ll be using the marvellous photos from Tash in that post.