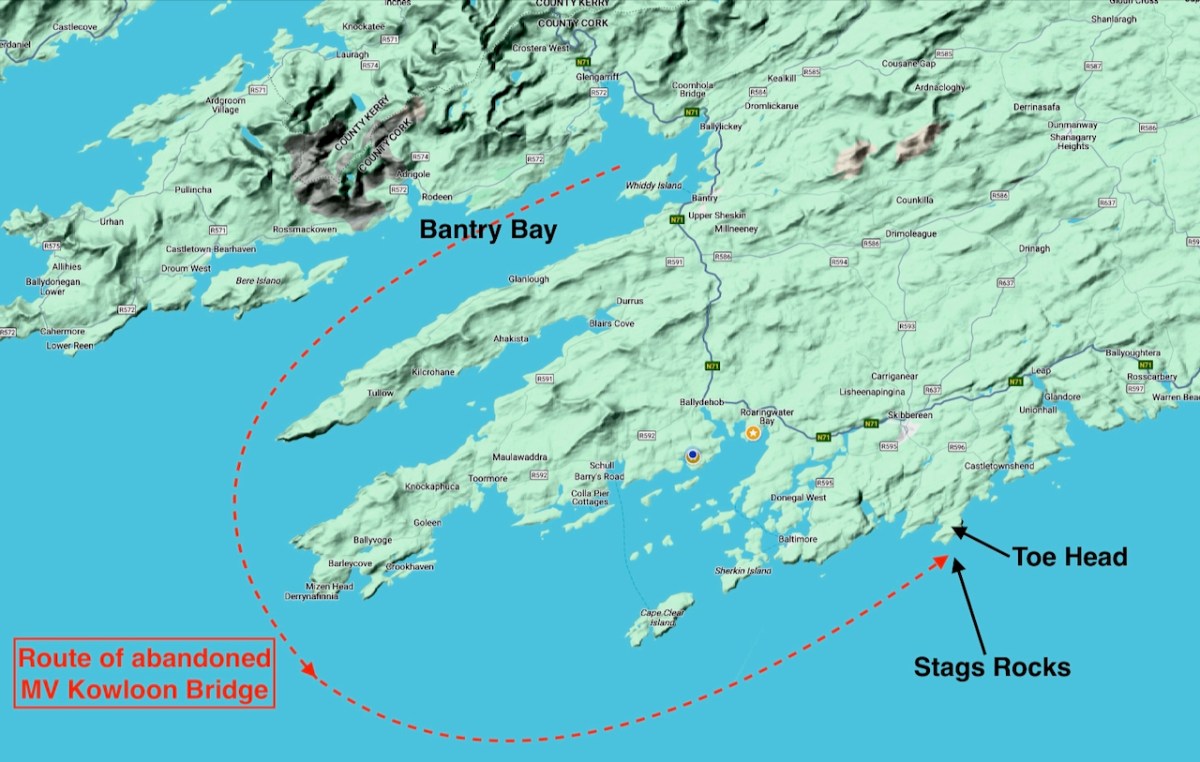

We’re going back a few years to look at a piece of West Cork history: a shipwreck. The ship is the Kowloon Bridge, a Bridge class OBO (oil/bulk/ore) combination carrier built by Swan Hunter in 1973. She ended her days on the Stags Rocks, beside Toe Head in West Cork in 1986 (above – image courtesy of Irish Examiner). At the time, this was said to be ‘one of the largest wrecks in maritime history’.

A Bridge Class model (above – photo courtesy www.mikepeel.net). Six of these ships were built by Swan Hunter at Haverton Hill on the River Tees in County Durham, UK, between 1971 and 1976. Originally named English Bridge and subsequently – passing through various ownerships – this 54,000 tonne vessel was renamed Worcestershire; Sunshine; Murcurio; Crystal Transporter; and finally Kowloon Bridge. I’m tempted to think of the old folk belief that says changing the name of a boat is unlucky!

. . . Perhaps the most famous maritime superstition of them all is the idea that changing the name of a ship is bad luck. Legend has it that Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea, has a ledger in which he keeps track of the name of every sea-going vessel. Changing the name is seen as a challenge and as an attempt to try and out-smart him, which would incur his wrath. To avoid any bad luck, the original name must first be purged from Poseidon’s book in a de-naming ceremony, before the new one is adopted . . .

National maritime Museum, Cornwall

There she is, in her original incarnation and unladen (image courtesy of Tony Ecclestone, Swan Hunter). As you can see, a massive vessel. Her length was 295 metres and her beam 44.3 metres. She had a draft of 18.5 metres. In November 1986 the Kowloon Bridge – which she had then become – departed Sept-Îles, Quebec, bound for the River Clyde in Scotland. Her cargo was 160,000 tonnes of ‘marble sized’ iron ore pellets and crude oil.

The Atlantic crossing was particularly rough-going, and the vessel sustained some superficial damage. The decision (a fateful one) was taken to head for the nearest shelter on the east side of the ocean: the deepwater Bantry Bay, off West Cork’s coast. A Lloyds’ survey there showed that she had suffered ‘routine heavy weather damage’ and recommended that she remained anchored in Bantry Bay while temporary repairs were undertaken. Here’s a view of Bantry’s waterside in more benign days: Roaringwater Journal has reviewed the town in some detail.

Above is a RWJ view of Bantry Bay and Whiddy Island taken back in 2014. The island was the setting for another disaster in earlier years: on January 8, 1979, the French-owned tanker, Betelgeuse, exploded at the oil terminal, resulting in 51 deaths. Even now – 45 years on – new enquiries are being set up to establish the true facts surrounding that incident. Returning to our Kowloon Bridge story, accounts seem to vary. One says that on 22 November 1986 – having had the necessary repairs completed – the ship resumed her voyage and set out into the Bay; but she was plagued by continuing bad weather, and lost her steering gear. Another suggests that the problems included ‘deck cracking in one of her frames’: she was forced to leave port to avoid colliding with another tanker and – engine running astern – she lost her anchor and her steering controls. The decision was taken to abandon ship (still running astern) and Royal Air force helicopters rescued the crew. She headed out of the bay and into open waters, being driven also by storm-force winds. (Image below courtesy of Southern Star)

Kowloon Bridge left Bantry Bay and rounded the Sheeps Head and Mizen Head. A tug tried to intercept her, but was unsuccessful as this, also, sustained damage due to the adverse conditions. Coming close to Baltimore the combination carrier/tanker hit rocks and her engine stalled. She continued to drift eastwards, finally coming to rest on the Stags Rocks below Toe Head (header pic).

Despite efforts to board her and assess salvage attempts (images above courtesy Irish Examiner), in due course the ship broke her back and went under – although, according to local reports, her bow could still be seen for months afterwards. To this day she lies off the rocks, with her iron ore cargo surrounding her. Below: the view from Toe Head today and (lower) the Stags Rocks.

The breaking up of the ship caused the release of of 1,200 tonnes of fuel oil. This led to damage to local coves and beaches, with loss of income being suffered by the fishing and tourism industries. The incident happened in the days before The International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation was set up: that came into being in 1990. Parties to OPRC are required to establish measures for dealing with pollution incidents, either nationally or in co-operation with other countries.

. . . Ships are required to carry a shipboard oil pollution emergency plan. Operators of offshore units under the jurisdiction of Parties are also required to have oil pollution emergency plans or similar arrangements which must be co-ordinated with national systems for responding promptly and effectively to oil pollution incidents. Ships are required to report incidents of pollution to coastal authorities and the convention details the actions that are then to be taken. The Convention calls for the establishment of stockpiles of oil spill combating equipment, the holding of oil spill combating exercises and the development of detailed plans for dealing with pollution incidents . . .

International Marine Organisation

Entry into Force 13 May 1995

Trying to follow the subsequent story of the wreck, everything gets a bit murky. West Cork communities undoubtedly suffered as a result of the foundering. Debris and oil were washed up (image above courtesy Irish Examiner). ‘Hundreds of seabirds’ died according to local reports. Promises of compensation were made – and reneged on – by the Haughey government. But it was Cork County Council and its ratepayers who eventually bore the major costs of cleaning up, even though the ship had been fully insured (image below courtesy Irish Examiner).

Apparently, the wreck was purchased in December 1986 by a British scrap dealer, Shaun Kent. One report states he paid a million pounds for it – another states he paid one pound for it! An article in the UK Independent newspaper in August 1997 describes how he planned to use high power water jets to wash the iron ore pellets to the surface for recovery. Their value was said to be in the order of millions. He also intended to recover the steel hull and other elements. However, concerns were expressed locally and nationally that such a process so long after the event would adversely disturb the seabed and the stable micro-environment which has evolved over time. It is unlikely that such plans will ever be acted on.

Today, the wreck is an attraction to underwater enthusiasts (images above courtesy of Extreme Sports Cork): Nature has taken over the intrusion to the sea bed. During the various discussions which have ensued in the many years since the Kowloon Bridge came to rest on the Stags Rocks, the question has been raised: was the ship seaworthy in the first place? It is pointed out that a sister ship was MV Derbyshire. Originally named Liverpool Bridge, she was launched in 1975, the last of the six Bridge Class ships. With a gross register tonnage of 91,655 she had the greatest volume. In July 1980, Derbyshire also left port from Sept-Îles, Quebec, bound for Kawasaki, Japan. She was overwhelmed by a tropical storm, and sank in deep ocean, with the loss of all 44 lives on board. This was in fact the largest British ship ever to have been lost at sea (image below courtesy of shipsnostalgia.com).

The four remaining Bridge Class vessels saw long service, and were eventually scrapped, so there is no reason to suggest that the design was in any way faulty. I suppose we might say that it is mankind’s folly to create such huge machinery to bring cargoes across the world. We challenge Poseidon, and he has to take his share (image below courtesy of Bardo National Museum, Tunis).

I am grateful for access to records at the time in the local and national media: in particular The Irish Examiner, The Southern Star, The Irish Times and RTE

Discover more from Roaringwater Journal

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I remember this so vividly. I was in school and my mother collected us early as our farm was overran with spectators. I remember collecting timber, flares , ropes etc that were washed ashore in the following months from the Kowloon Bridge. I still farm on toe head today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, Darragh – it’s good to hear these first-hand accounts. And the spectators – there’s another dimension! I bet that carried on for a good while?

LikeLike

A fascinating story, Robert. Thank you, and for all those lovely pictures of Toe Head and the Stags. I spent my Wartime summers as a child, living with my Grandfather in Castletownshend, we had only a pony and trap for transport, and a smaller pony for me .(My brother was older so rode the wonderful Welsh pony who pulled the trap) My mother bought a brand new Raleigh bicycle for herself to bike to the station when she wanted to go somewhere (she went to Dublin like that with the bike carrying her across Cork to the other station to go North).

Our usual expedition was to Sandy Cove, and she had 2 metal rings put into the cliff face to tie up the ponies while we swam and played in the sand and on the rocks. One of the rings is still there – or was when I was last there a couple of years ago – more or less opposite the bottom of the steps – there were no steps then. Sometimes we rode the ponies into the sea too.

A longer expedition was to Toe Head, and those extraordinary shapes of the Stags are etched in my memory from that view and also from rowing and sailing in the Castletownshend area. I agree it looks like a wrecked ship, it really is a fascinating coast with those deep cracks between the slabs of slate, especially in that view from above

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anne – we always appreciate your comments: thank you. I just want to rush straight out to Sandycove and see if that ring is still there!

LikeLike

Finola asked the question: where did the Royal Navy helicopters come from to rescue the crew who abandoned the ship? That must have been quite a job in those conditions. Anyone know?

LikeLike

She was colossal! What an eventful voyage and sombre end and such conflicting reports. You’ve amassed some excellent and varied illustrations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a fascinating story to follow, Amanda!

LikeLike

This is a completely transfixing report which brings back so many memories of the time. Well done Robert. I love the Poseidon bits too ! I love it all in fact !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, Julian… You are very kind!

LikeLike

Well, not kind, just truthful and grateful! In another life you could be a top journalist or something! You had everything there. I have often walked out on Toe Head with my dogs, and gazed against the wind at the Stags, which in themselves seem to me to resemble some sunken battleship, in certain lights. What a drama the whole thing was! What a story! You have done justice to it all. And now I must turn my attention to Finola’s post on St Brigid , which looks rather entertaining ….. !!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved the piece about the Kowloon Bridge Robert. You wouldn’t know this, but my then boss Dick Spring was Minister for Energy in the government of the day. He was involved in controversy, and under pressure, because he refused to give free gratis licences for oil drilling and exploration off the Irish Coast. It made him particularly unpopular with his partner in Government Fine Gael, because they were close to Tony O’Reilly, who owned more or less everything in Ireland back then – including Atlantic Resources, an oil drilling company. He (they) expressed constant frustration with Spring, who was adamant that anyone exploiting Ireland’s natural resources, including gas or oil, should pay something for the privilege.

In the middle of all that the Kowloon Bridge sank. There was a Dail debate about the disaster and the consequent pollution. In the course of it your then local TD, PJ Sheehan of Fine Gael, said “we should have put Spring in charge of the rescue. Because then, damn the drop of oil would come ashore”.

Fergus

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fergus, it’s great to hear from someone who has direct memories of the incident. I have been asking around but most peoples’ recollections are a bit hazy… I was also particularly struck by how different the various media accounts were. In some cases they contradicted each other completely! But I also got a lot out of trying to put together as complete a story as possible. I don’t have the knowledge to comment on the politics of it all, however. So, thank you for your contribution.

LikeLike

Hi Robert,

Thanks for the story, it brings back memories for me too, as my Dad Tom Nash was the pilot on board, he strongly advised the captain not to leave Bantry, as it was safer there until the repairs were completed. Unfortunately, commercial pressures by the owners wanted her in Rotterdam for out of water repairs, this resulted in her sailing from Bantry that night and the rest is history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s good first-hand information, Paul. Another dimension to the story…

LikeLike

I remember so well the aftermath of the Kowloon Bridge disaster because Tow Head was a favourite place for us to picnic and Bill to paint. For years after the event those beautiful grey stones with slivers of quartz that the beach had in abundance were covered in pieces of a black substance that started as sticky, then became more elastic before turning into hard shards and (presumably) floating away. The Kowloon Bridge left many such sad sights around our coast.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Katharine, many thanks for reading the post, and for your comment. I was keen to find some contemporary local memories. Best wishes.

LikeLike