When studying architecture (fifty years ago!) I had little time for what was then generally termed the Victorian Gothic style. It seemed to me derivative, dark and fussy. Now, half a century on, I am suddenly a convert – and all because of a visit we made to Adare Manor: surely one of Ireland’s leading five star hotels, but also the finest embodiment of Neo Gothic attributes that I have come across in any building to date.

The settlement of Adare, in County Limerick, is a bit of a traffic bottleneck waiting to be sorted out – by a much yearned-for bypass which is likely to take a few years to complete. Once in the village, however, you will find a magical and slightly surreal place with its clusters of picturesque thatched cottages, pubs and restaurants, art galleries, antiques vendors and the greatest concentration of fashion shops and boutiques outside of any city in Ireland (probably). But when it comes to hospitality and architecture, then Adare Manor itself beats all contenders.

From the superbly landscaped gardens (top – there are 840 sweeping acres on the estate), through to elegant interiors (the drawing-room, centre, is a prime example), the mansion is on a grand scale and very much reflects, today, the spirit in which it was reincarnated in the 1830s (lower – the Great Hall) by the splendidly monikered incumbents of that time: Windham Wyndham-Quin, 2nd Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl and his wife Lady Caroline Wyndham, heiress of Dunraven Castle, Glamorgan, Gloucestershire.

The Manor House as remodelled by the Second Earl is a riot (Dunraven ravens, above). Known to have always actively pursued outdoor life, riding, hunting and sports, it is said that Windham was laid low by an acute attack of gout. Lady Caroline encouraged him to channel his frustrated energies into a building project: to modernise and enlarge their modest Georgian residence. The Earl rose to the challenge and embraced the exuberance of the fashionable Gothic Revival style of architecture.

Adare House in the 18th century (top) and its transformation by the 2nd Earl (lower – a 19th century engraving). Clearly funds were not a problem, as a stone plaque on the south elevation attests (one of many texts embedded in the refurbishment of the fabric):

…This goodly house was erected by Windham Henry Earl of Dunraven and Caroline his Countess without borrowing selling or leaving a debt AD MDCCCL…

Inspiration for the architectural elements came from an early 19th century romantic revival of interest in all things medieval: particular a perception of the trappings of chivalry: knights in armour, courtly love, stately homes, heraldry, jousting and country pursuits (you’ll see in Finola’s post that we indulged in some of those!). As the Victorian era progressed in the British Islands, these ideals evolved through art – the high point being the Pre-Raphaelite movement – and literature, as espoused in Malory’s Morte D’Arthur, for example, with its interpretation and embellishments by Tennyson and Beardsely:

In respect of architecture, the 2nd Earl was ahead of his time in pursuing medieval themes and must, surely, have been endowed with a good sense of humour. Lady Caroline always loyally stated that all the ideas in the remodelled house were Windham’s; however, we know that the ‘Gothic architects’ James and George Pain were involved, as were Philip Charles Hardwick and Augustus Pugin, in a project that spanned three decades.

You can see from this one small corner of the Manor the richness and quantity of detailing that was incorporated into the architecture, both inside and out. The 2nd Earl must have dreamed up or approved of all the themes which are well worth studying at length. Here are only a few of the gargoyles which attracted our eyes:

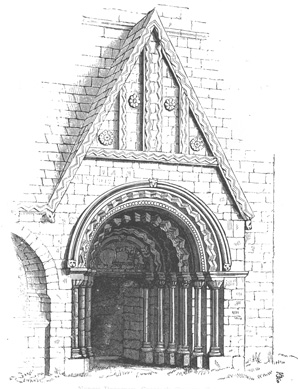

The 1897 photograph, above, shows the carriages of the Duke and Duchess of York at the entrance to Adare Manor. The Duke became George V in 1910. Everyone who comes to the Manor has to enter through a magnificent ‘Romanesque’ doorway (eat your heart out, Finola!) – whether royalty, like the party above, or mere mortals like us, who treated ourselves to a stay to celebrate our wedding anniversary. Have a look at the detailing on the architraves:

The craftsmen stonemasons of Adare were kept very busy – and fully employed – throughout the building period, which encompassed the worst years of the Great Famine. As were the woodcarvers. One room in the Manor – the Long Gallery – spans the whole width of the house: 40m long and 8m high. It’s now the ‘informal’ dining room. It has a magnificent array of carving, some – the choir seats – brought in from Flanders and dating from the 17th century (see the enigmatic example in the first photograph below), but most purpose-made locally for the new Manor. Each one tells a story. We need to go back again and spend more time there (please) just to even get a glimpse of all of them. By the way, if you want to see real medieval carving, have a look at this post of mine, from the West meets West series.

Lady Caroline was just as industrious as the Earl in contributing to the project and in creating employment through the famine. She established a School of Needlework to develop marketable skills and opportunities for local women: some of the work of the School graces the walls of the Manor. In fact, the work of local craftspeople is prominent throughout the interior of the building. Below left is the Long Gallery, showing off decorative work on the ceiling, tapestries and stained glass. On the right is a carved stone figure that looks down on guests in the Great Hall.

All of the above is just a taster for the wealth of architectural delights that awaits future visitors to this hotel. We were among the first: the Manor re-opened after a full two-year refurbishment and extension the week before we took our stay there. We can confirm that the standard of this establishment is among the highest that we have come across in all our travels in Ireland. Every detail has been thought out: rooms are spacious and warm; beds are large and comfortable; all mod cons are incorporated – right down to a switch beside the bed which opens or closes the curtains! The food excels – and we have yet to sample the full restaurant facilities. Above all, the service is faultless, welcoming, attentive and personal. Amongst the new features is a ballroom, which would make the ultimate wedding venue, built in a style which fully compliments the character of the original architecture:

Flamboyant, exuberant, playful, grand… I will run out of epithets, and superlatives. I was just – delighted – by Adare Manor, and we feel privileged that we can still appreciate the aesthetic wit which the Earl and Lady Caroline brought to the house, and which has been extended by subsequent generations: the last Wyndham-Quin to inhabit the property – the 7th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl – moved out in 1982. Lady Caroline should have the last word: she wrote this in her 1856 book Memorials of Adare Manor…

This charming spot was my home of unclouded happiness for forty years: may Heaven’s choicest blessings be poured with equal abundance on its present and future possessors!