The forerunners of the museums that we visit today were known as ‘Cabinets of Curiosities’. Starting – just about – at the very end of the sixteenth century – we find mentioned and illustrated collections of objects gathered from exotic places: things that a gentleman might be unfamiliar with; things that could expand our knowledge and cause wonder. Curiosities, undoubtedly. Here’s one collection illustrated in 1599:

This is an engraving from Ferrante Imperato’s Dell’Historia Naturale (Naples 1599), the earliest illustration of a ‘natural history cabinet’ (courtesy Oxford University). It shows a room fitted out to display imported paraphernalia: (hopefully mounted) creatures, dried specimens, fossils – also books and illustrations. The collector here takes on the role of educator – perhaps showman. Here you might encounter unicorn horns, a dragon’s blood, mermaid scales as well as the full sized alligator hanging from the ceiling.

Frans Francken the Younger, Chamber of Art and Curiosities, 1636 above (Public Domain). Another selection of paintings intermixed with fish, carved beads, sculptures, with on the table exotic shells, gem-stones mounted with pearls, coins and medals.

Rathfarnham Castle (above) is a good example of an Irish Fortified Manor House. This mainly seventeenth century building type would have been the relatively comfortable home of an aspiring clan – perhaps a titled family with church or merchant connections: Finola has written about a West Cork example. Austin Cooper – a tax collector who indulged his hobbies of sketching and writing while travelling through Ireland in the performance of his duties – wrote of Rathfarnham:

. . . What renders this a Place of any Note is the Cas. belonging to the E. of Ely. This Cas. is square, with a large square Tower at each corner – on the S. side in the Center is a semicircular Tower . . . The hall is but low, at the same time exquisitely elegant . . . The gallery is a beautiful room, at the far end is a curious cabinet of Tortoise Shell & Brass containing some most extraordinary Work in Ivory . . .

Austin Cooper’s Notes, rathfarnham Castle

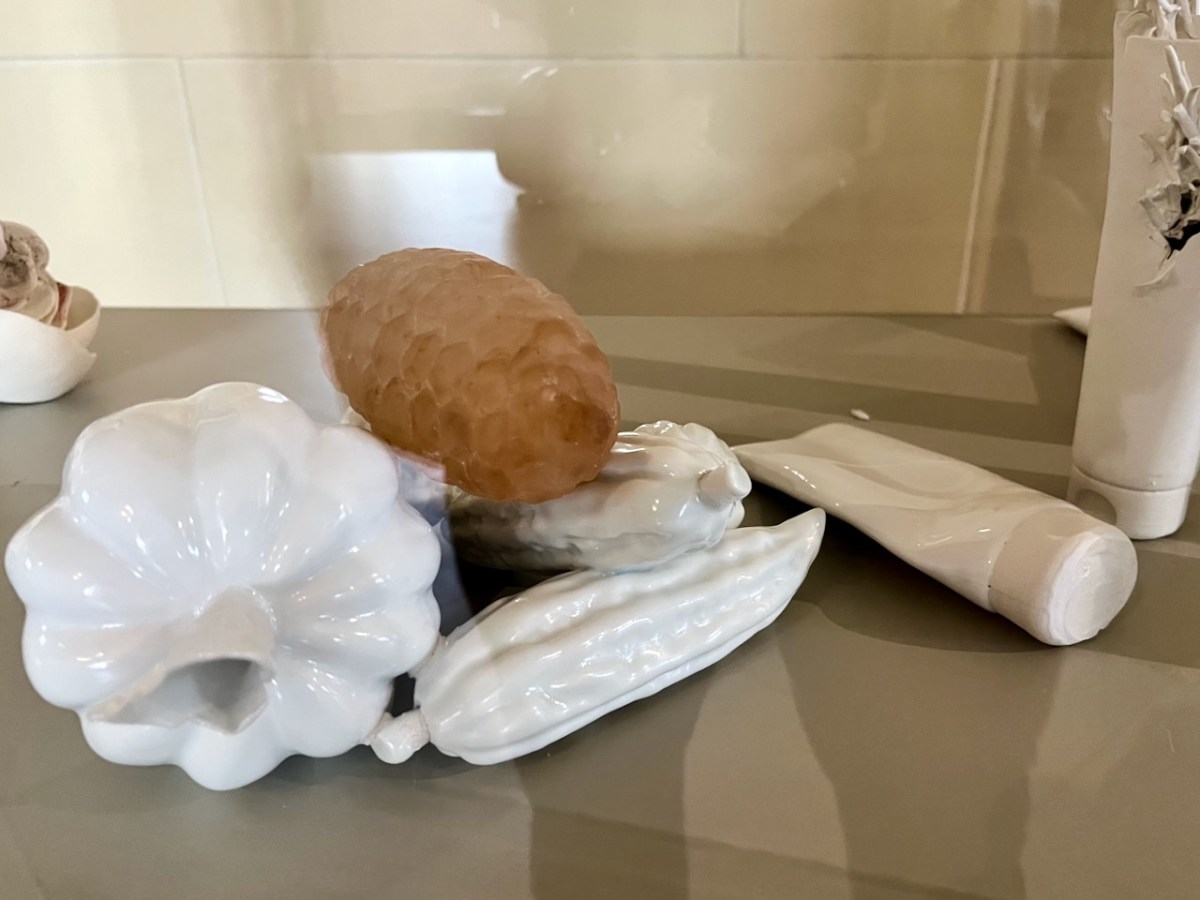

Rathfarnham Castle has, in modern times, a distinguished continuing association with contemporary ceramicists and in 2015 established a modern Cabinet of Curiosities which continues the tradition of displaying ‘extraordinary work’, and provides excellent material for a Sunday morning post!

The curiosities are not labelled – and nor are their creators. Peter Bagshaw, OPW at Rathfarnham, has kindly provided me with a list – thank you, Peter – attached at the end of this piece. I cannot necessarily individually identify each item: I will leave you to work out which might be which . . .

This eye-pot looks great when you pan out a bit . . .

This one certainly harks back to some of those manufactured creatures that turned up in cabinets of old.

Leather teapot – a fashion item, perhaps?

I think the final image might be my favourite: a young person clutching an angel’s wing? Could this be The Sequestrator?

List of pieces – not in any order:

The Sequestrator Roderick Bamford, Australia

Mosaic Parrot Fish Ilona Romule, Latvia

N.K. Red Lizard Cup Robert Harrison, USA

New Leather Teapot Xiaoming Shi, China

Eyes Tea Verne Funk, USA

Figure Leo Tavella, Argentina

All that promise Ting Ju Shao, Taiwan

Immigration Emilia Chirila, Romania

Black and White Rotation Sylvia Nagy, USA