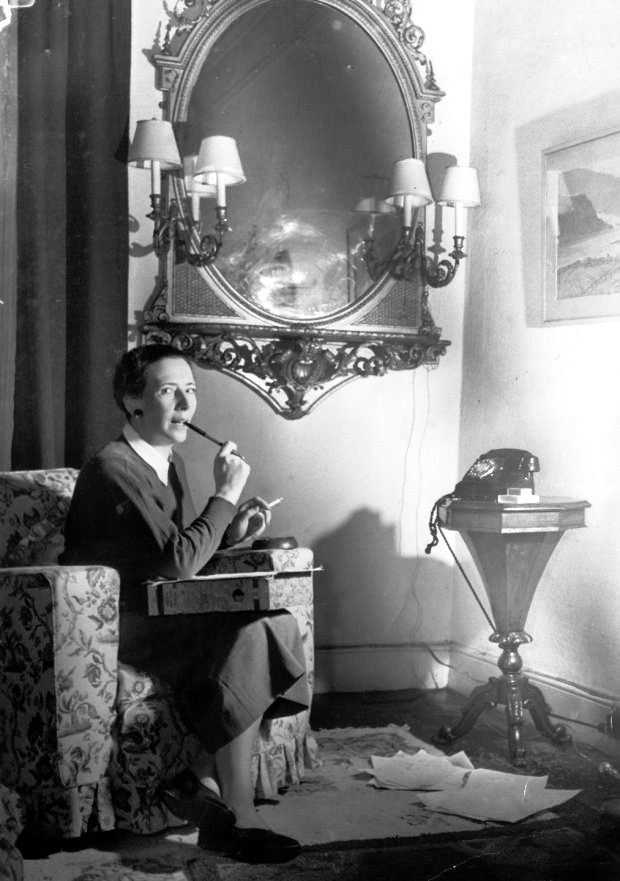

My friend Viv has loaned me her precious copy of Kind Cooking, given to her way back in 1977 by her mother-in-law, Molly – a wonderful matriarchal figure of my youth. It has plunged me back into the world of Irish cookbooks that I first explored with my posts on Monica Sheridan (Monica’s Kitchen, Back to Monica (about her famous Christmas cake recipe) and Monica Rides Again). Except this time it’s Maura Laverty, who predated Monica and who first established that bright, amusing, anecdotal style of food-writing that still defines the genre.

To open Kind Cooking is to be immediately reminded that Maura Laverty was, first and foremost, a writer. Author of several novels and later in life of a highly successful television soap opera, Tolka Row, she made her living as a writer at a time when it was not easy for a woman to do so. While I want to concentrate on Kind Cooking here, you can read in the Irish Times an excellent summary of her life by Seamus Kelly, author of The Maura Laverty Story: from Rathangan to Tolka Row which was launched to much acclaim earlier this year. (The book is available in shops and directly from the author. Enquiries to james.a.kelly55@gmail.com)

Seamus Kelly with son, Peter, and daughter, Laura, launching ‘The Maura Laverty Story’ in Rathangan Community Centre. Photo by Tony Keane

Most people in Ireland would be more familiar with Maura’s Full and Plenty, still a vivid memory from our mothers’ row of cookbooks, and for some a much-thumbed staple. It was her best seller and the food book she is still most remembered for.

This image is courtesy of the lovely food blog Eating for Ireland – the author uses it (her Mum’s copy) to make Apple Betty

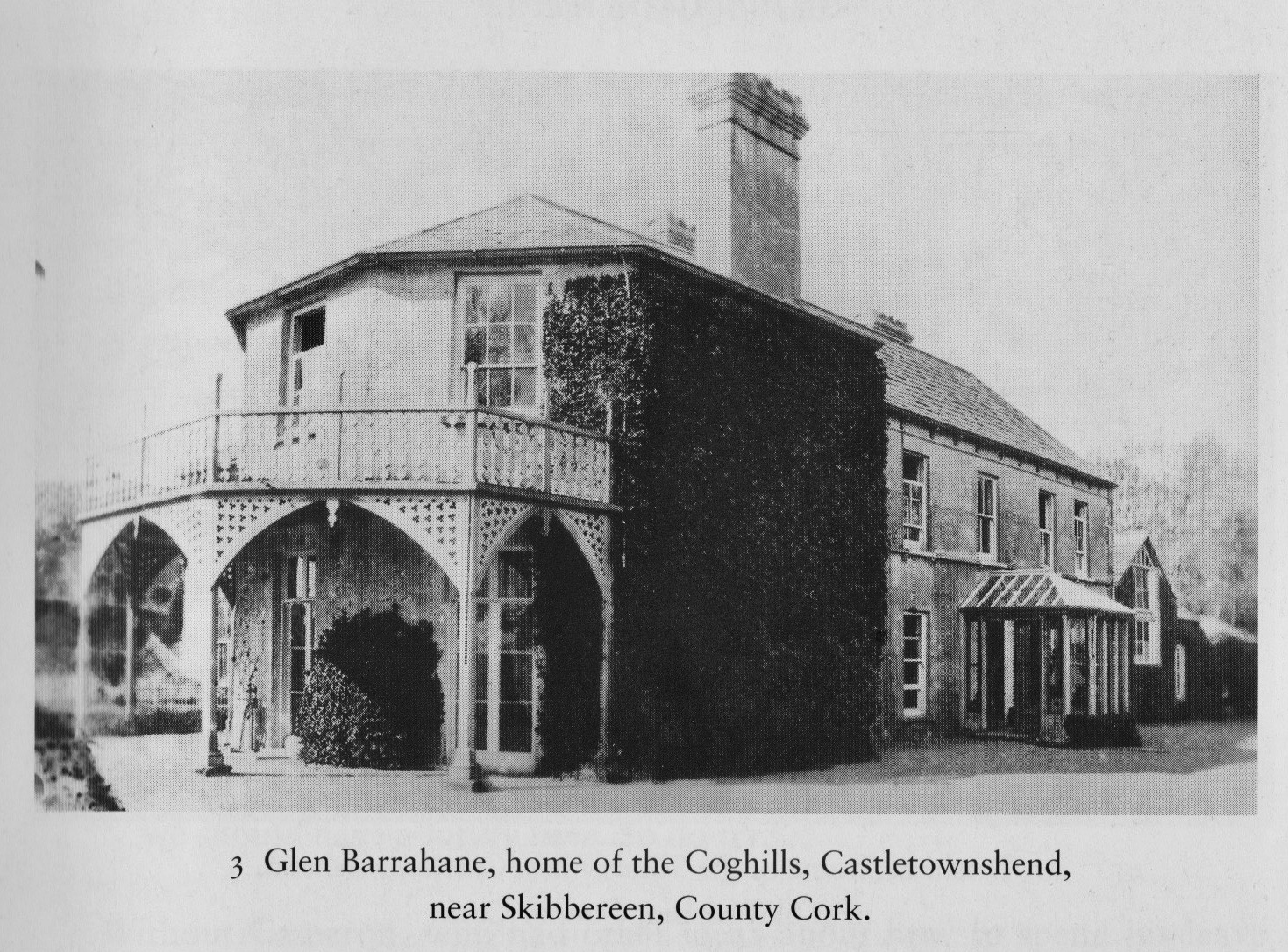

Kind Cooking was published first in 1946. There is no date on Viv’s copy, but it is possible that it was given free when you bought an electric cooker, since it was published by The Electricity Supply Board. Although this one has no illustrations, subsequent issues had this photograph. Anyone can cook, apparently, with one of these new all-electric kitchens!

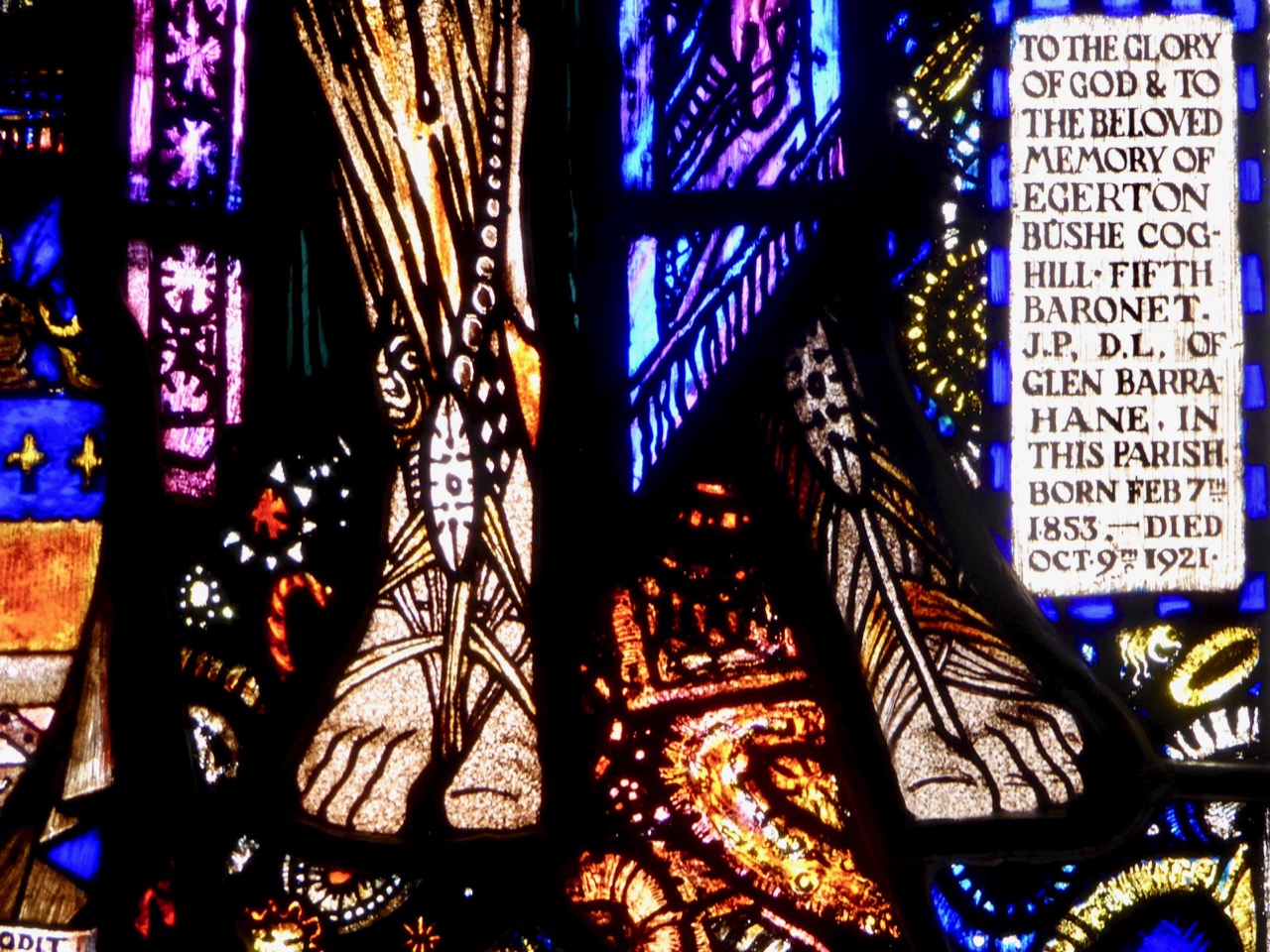

It was published several times again, including an edition with the new title Maura Laverty’s Cookbook. One edition was brought out by The Kerryman, with a section on diet by Sybil le Brocquy and ‘decorations’ by her son, Louis le Brocquy.

From the start, the emphasis is on a warm, chatty, non-intimidating approach to cooking and on traditional recipes – barm brack and soda bread, rowanberry jam, Irish custard, champ (although she calls it Thump), liver loaf (a friend of mine, working as a camp cook, was once fired for feeding this to a gang of road-builders) and lots of organ meats – tongue and mushroom, anyone? I will spare you a description of how to make a delicious and nutritious broth from a whole sheep’s head – even she calls it a ghastly, cannibalistic business.

Part of the index – including a whole section on rabbit

But Maura had lived abroad and had developed a taste for garlic, French onion soup, Swedish and Danish meat balls, Spanish rabbit. Hamburgers (called hamburghers) could also be made into Hamburg stew and hamburgher rolls. Some recipes contain ingredients we don’t use any more – anyone know what griskins are? How about forcemeat?

I wonder how this accords with our modern food pyramids

She wasn’t above convenience cooking, although she does warn you, in the introduction to her Corned Beef Hash, There is an enduring something about tinned corned beef that makes it as easy to detect as a legless fugitive with cauliflower ears and a cast in his eye. Disguise it how you will, your tin will find you out. Still, you can always try.

One of Louis le Brocquy’s ‘decorations’

It is this – the conversational, anecdotal tone, that Maura pioneered and that made her cookbooks so entertaining and beloved. You can sit and read them for pleasure as easily as you can use them to find a recipe. Her Fowl section starts with a two page story about Mag Donnelly – I am sharing it with you in full, below, as an example of the delights within these covers.

Since you’re probably thinking of Christmas dinner around now, I should tell you Maura’s secret to choosing a good turkey: Nice smooth black legs with short spurs and limber, moist feet are signs of youth and beauty in a turkey. Look into its eye. They should be full and bright. A turkey with sunken, bleary eyes is definitely unsuited to roasting.

You can just imagine her telling you about how to choose a turkey – Listen to me now

She’s a big fan of vegetables. In our place she says, we were acquainted with only six kinds of vegetables: onions, cabbage, turnips, boiled potatoes, mashed potatoes and potatoes steamed in the baker. The only people who grew such rarities as peas, beans, parsnips and carrots were the Protestant peelers. . . Their vegetable growing, in common with their Sunday school and their red, white and blue badges, was part and parcel of Protestantism and foreign aggression and we felt it couldn’t be good or lucky.

Cheese, especially good cheese or anything foreign, was a bit of a rarity when I was growing up. When Maura was a child it was all but unknown. Introduced to good cheddar she developed a passion for it. Since she was wondering at the time if she had a vocation as a nun, she felt it was important to ask her favourite teacher, Sister Mary Declan:

“Would Reverend Mother let you go to the press for bread and cheese any time you’d take the notion?”

Sister Mary Declan’s eyes grew round in her wrinkled face, and her eyebrows climbed up under her coif in horror.

“In heaven’s name, child,” she cried, “what kind of a poor excuse for a nun would I want to be to go gratifying my sinful appetites in such a manner?”

. . . She would be sorry to know that her reaction to my question about the cheese killed the vocation stone dead in me.

I will leave you with a couple of examples of Maura’s approach to conjuring up images of food. In the chapter on cakes she invites us to set our sub-conscious to work on any food item until an association has been evoked. She gives several instances of her own association but here are two of my favourites.

BLACK PUDDINGS: To think of these is to think of the Gunner Doyle, an ex-British Army man, who always drank more than was good for him on pension days. On ordinary occasions the Gunner would run from his shadow. His own mother said that in his sober senses he wasn’t fit to wash bibs for babies. When the drink was strong in him he would stand at the pump and roar an invitation to all Ballyderrig to come and be made into puddings.

TOAST: I can’t separate this from Maria Duffy at home in our place who, for fourteen years before God took her, never opened her lips to her husband – and all on the head of a piece of toast. She had a passion for toast. Cake-bread [home-made white soda bread] doesn’t toast well, so when Mrs. Duffy came into town (which she only did once a week for they lived away out in the depths of the bog), she treated herself to a baker’s loaf. Jem Duffy had a passion, too. His was for fishing. Someone told him that loaf bread made grand ground bait. He asked his wife for a slice. She retorted that with only the heel of the loaf to last her until Sunday, she saw no sense in casting her bread upon the water. Jem stole the bread when her back was turned. She never forgave him.

Thank you, Viv, for this treasure

I know I will go back to this book again and again, not for the recipes but for the opportunity to curl up and chuckle away an hour. As Maura says, Ingredients, skill and equipment are not so important to good cooking as a lively interest in human beings.