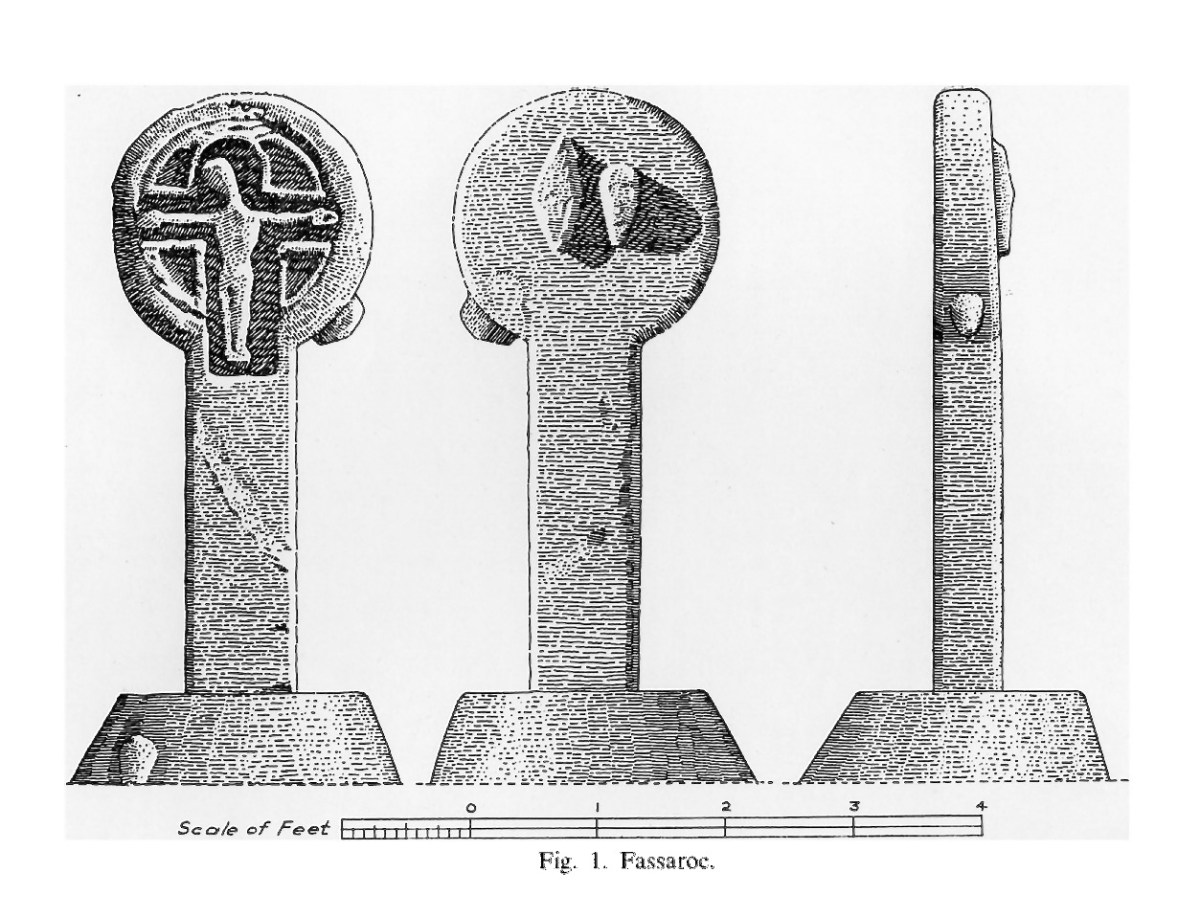

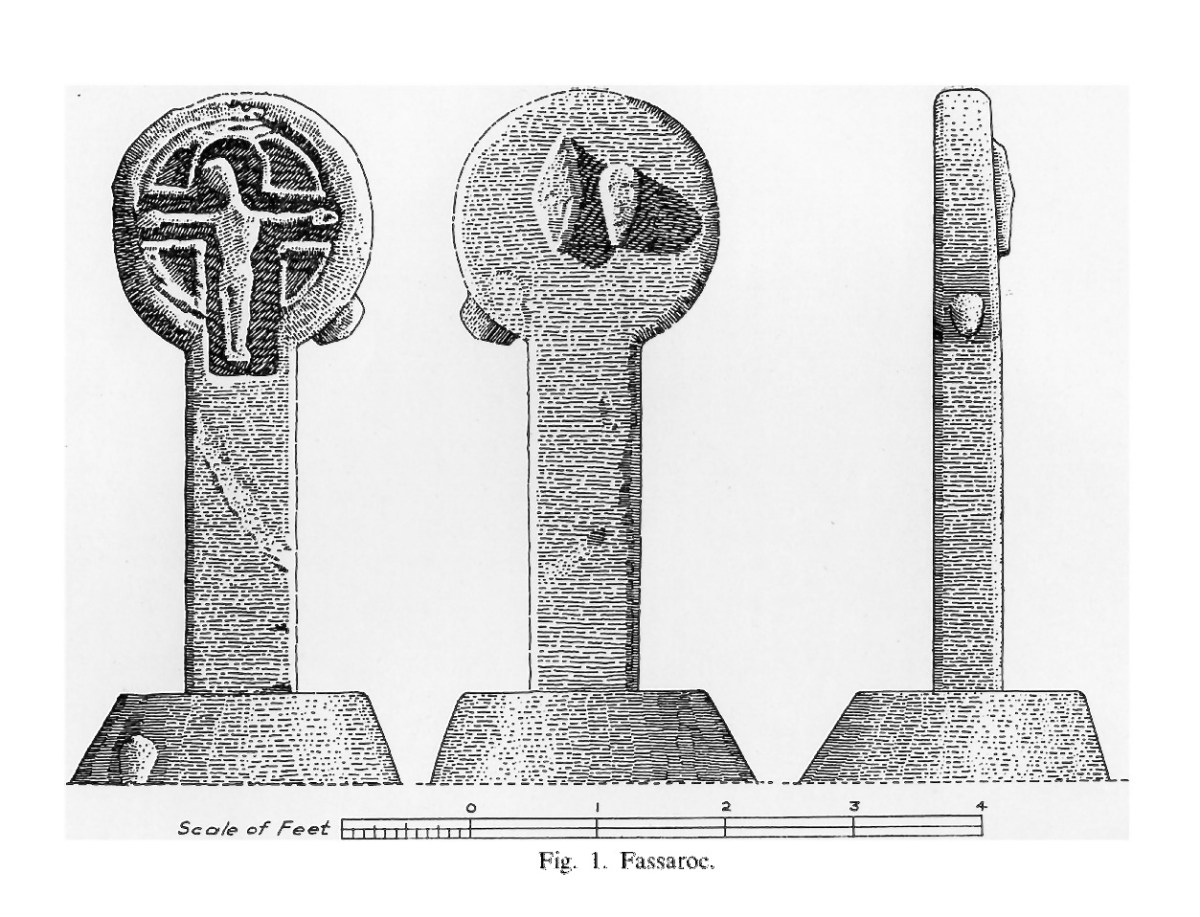

This is Part 2 of my examination of the Fassaroe Crosses of South County Dublin. In the first post I described the four crosses that comprise the Fassaroe-Type group, so well described and drawn by Pádraig Ó hÉailidhe. In this one, given that some authorities have claimed they may be of a relatively recent 17th century date, I will look at a probable dating horizon for those crosses, based on analogies with other Irish examples.

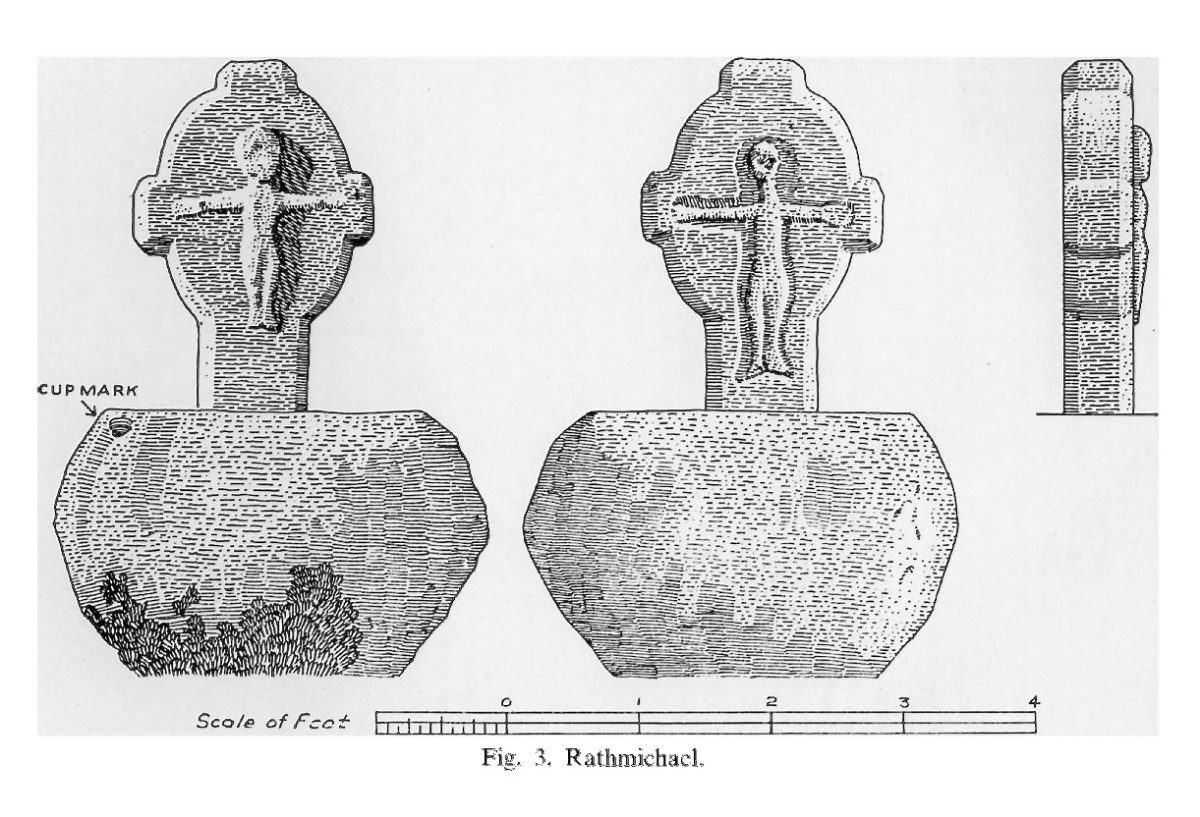

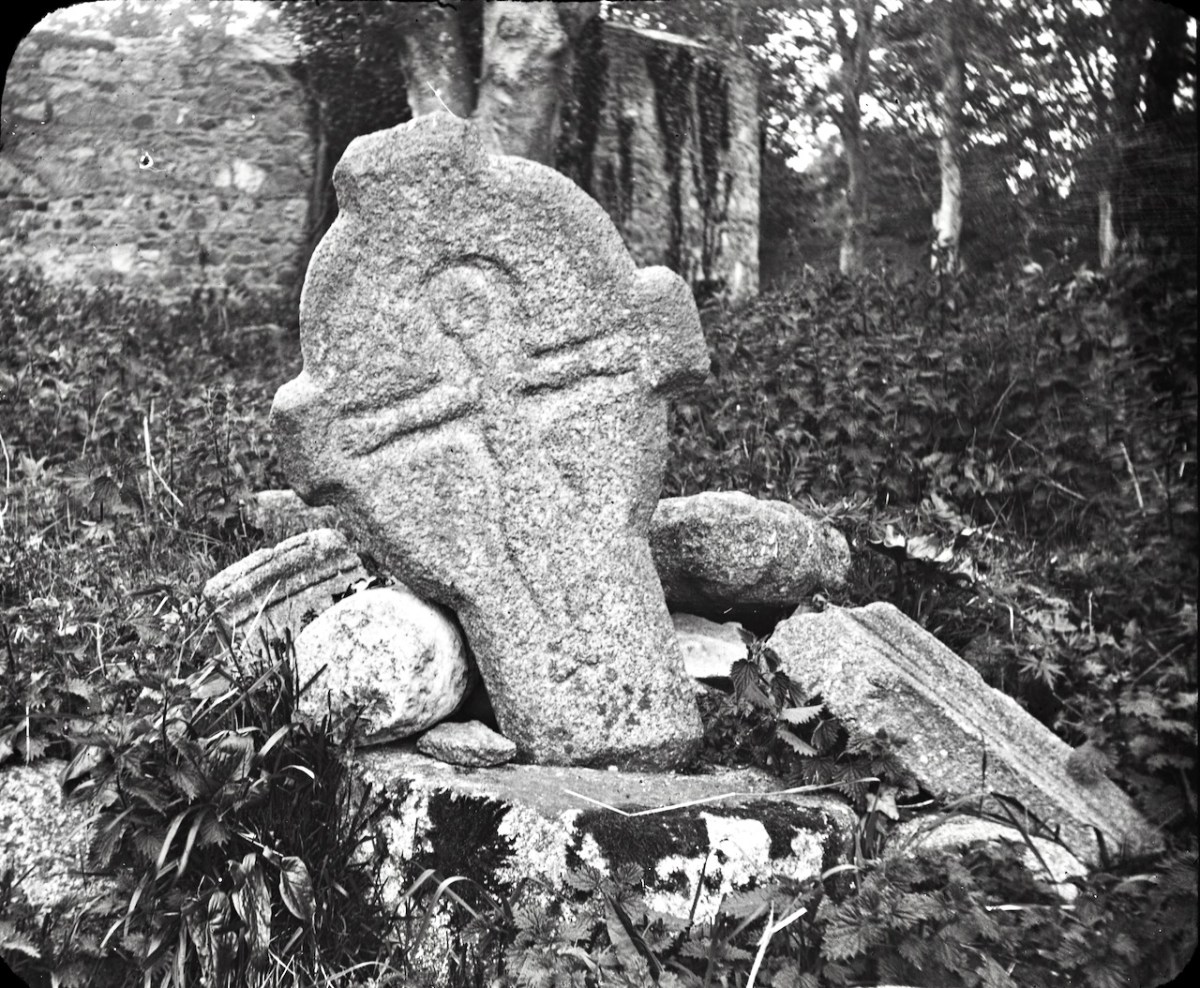

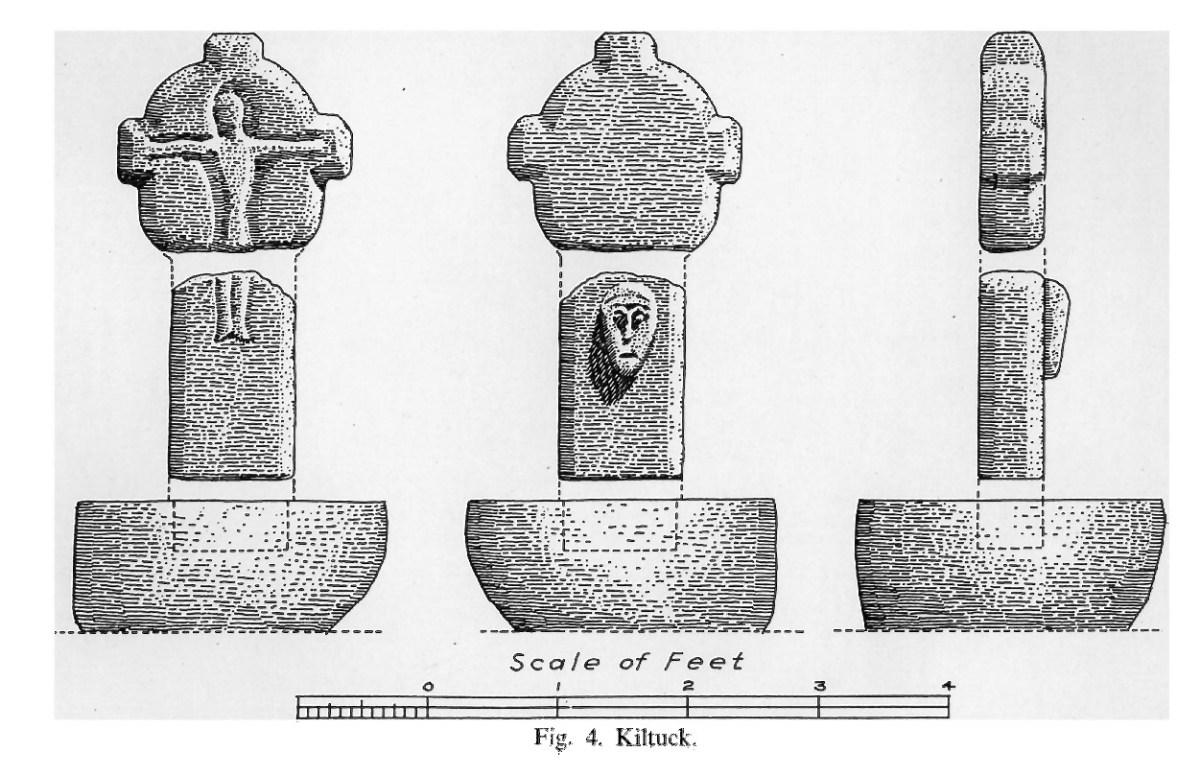

Let’s look first at the figure of the crucified Christ on the crosses at Fassaroe, Rathmichael and Kiltuck. It is immediately obvious that they are similar to each other in the slender shape and in the head, which is inclined or tilted to the right, and in the fact that the figure is recessed (although Rathmichael also has a figure in relief with no incline to the head). That tilt is pronounced on the Fassaroe cross but slightly less so on the figures on the Kiltuck example and the back of the Rathmichael Cross.

In the Kerry County Museum (the photo above is taken, with thanks, from their Facebook page) is a bronze figure, about 10cm long, probably once attached to a cross. It is dated to C1150 (I am not sure by what method since I cannot access the 1980 Journal article) and comes from Skellig Michael. The tilt of the head and the elongated figure are both clearly analogous to the Fassaroe-type figures.

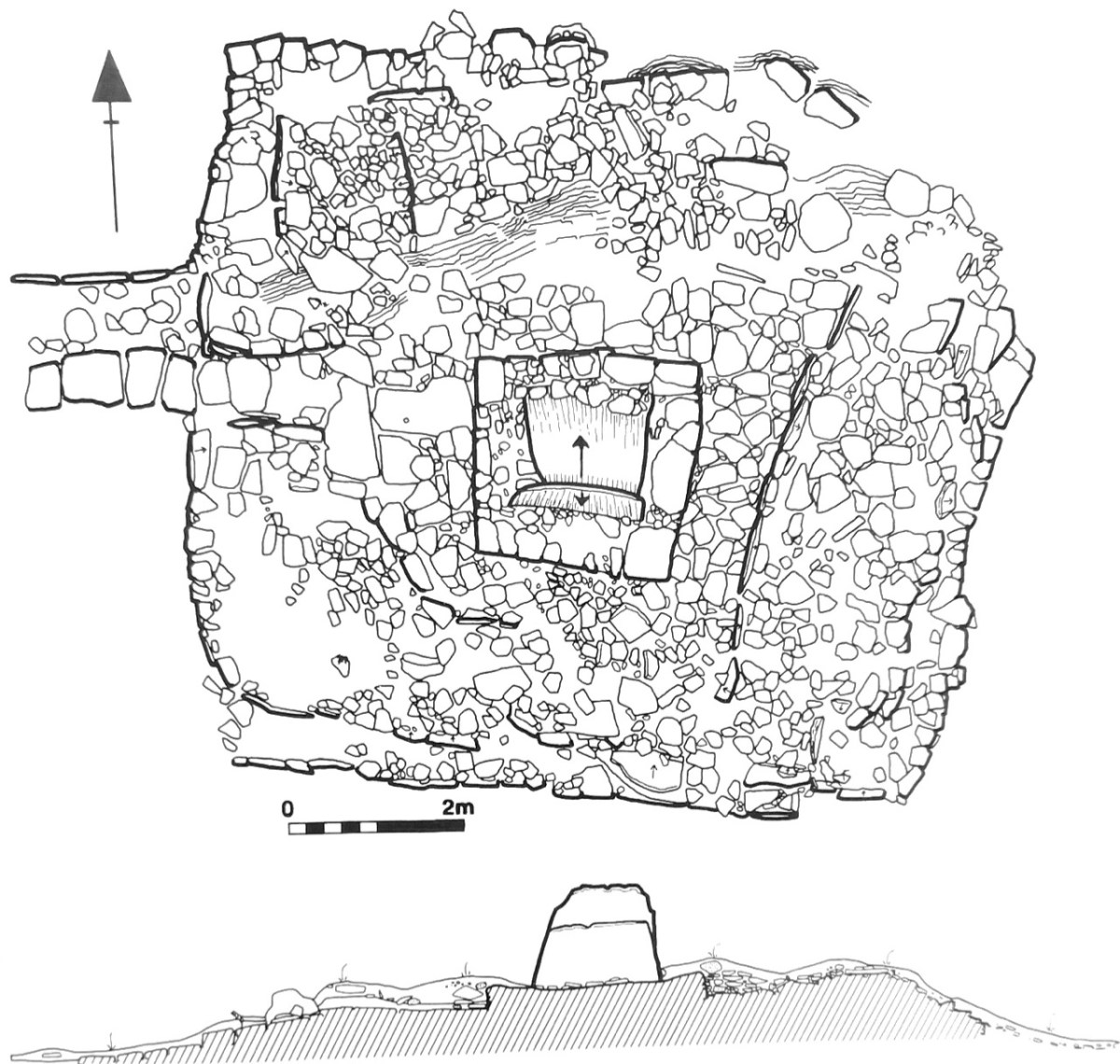

What about the shape of the cross-head? In Fassaroe this is a simple disc, while Rathmichael and Kiltuck have very short projecting arms. None of the South County Dublin examples have pierced heads, as in the classic Irish High Cross. We find similar crosses, in fact, in Ballymore Eustace (see this post in Pilgrimage in Medieval Ireland for more on that example – this image is from that post, with thanks), Kilfenora and Killaloe.

The Killaloe Cross, above, which actually came originally from Kilfenora, is perhaps the closest, and is dated to the 11/early 12th century. I have rendered my photograph in black and white as it is easier to make out that way,

There are several crosses in Kilfenora, associated with the 12th century church. Although they are more highly carved than the Fassaroe-type crosses, the unpierced disc form with the short arms can be seen on the back of the Doorty Cross (above).

The back face of the Tuam High cross, below, captured from a 3D image* although pierced, has a simple figure with an elongated and tilted head.

The Dysert O’Dea high cross (below) has several features of interest to us here. First, the conical mitre may be analogous to the Fassaroe head.

But it also points us to another monument close to the Fassaroe crosses – the Loughanstown Cross, below, now marooned in a new housing estate and very badly damaged. The form of the cross, however, looks quite similar to that of the Dysert O’Dea crosses while the projecting head (on one side) and the long figure (on the other) is also reminiscent.

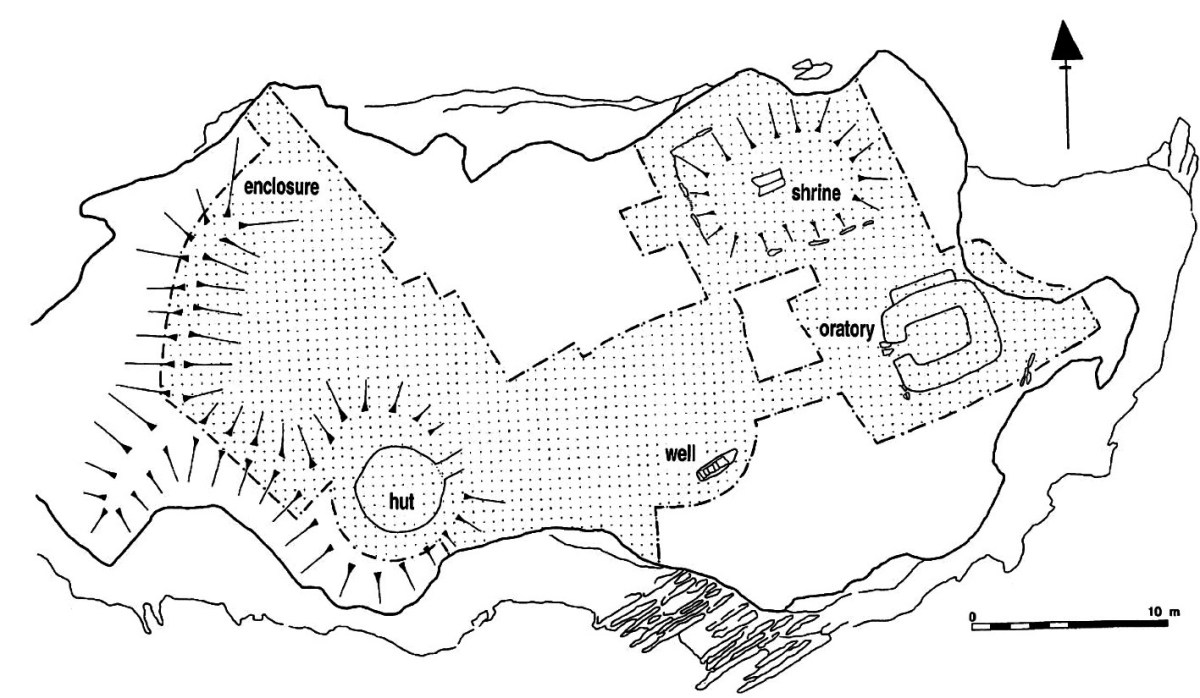

There is one more cross in the South County Dublin group which was situated in Killegar, about 4kms north-west of Fassaroe. It’s fragmentary, with only the disc-head remaining, containing on one side a simple crucified figure, with the head straight. In a piece for the JRSAI in 1947, Ó Ríordáin describes the other side as a cup-and-circle. This may mean that this cross was carved on the back of a piece of prehistoric rock art, but more likely that it relates it to the Rathdown Slabs, and brings us back full circle to the Rathmichael graveyard that Robert wrote about in his post Viking Traces.

The Rathdown Slabs slabs (also described and drawn by Pádraig Ó hÉailidhe, below) use that cup-and-circle form as part of their decorative technique, and are generally dated to the Viking period, or anything from the 9th to the 12th century.

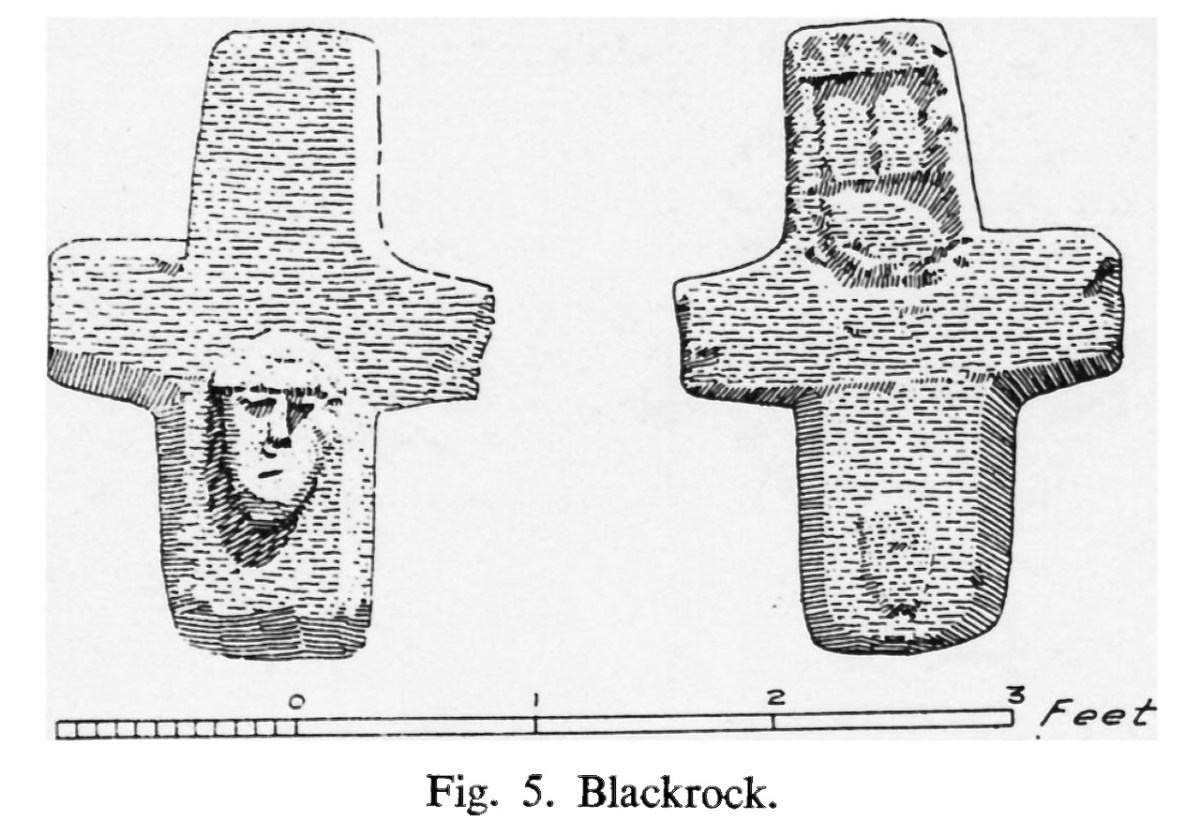

That leaves us with the Blackrock cross, different in form from the others, except for that projecting head . The only analogy I can find among my own photographs ties it firmly to the Romanesque period (12th century) – that cross is at Kilmalkedar in Kerry (below).

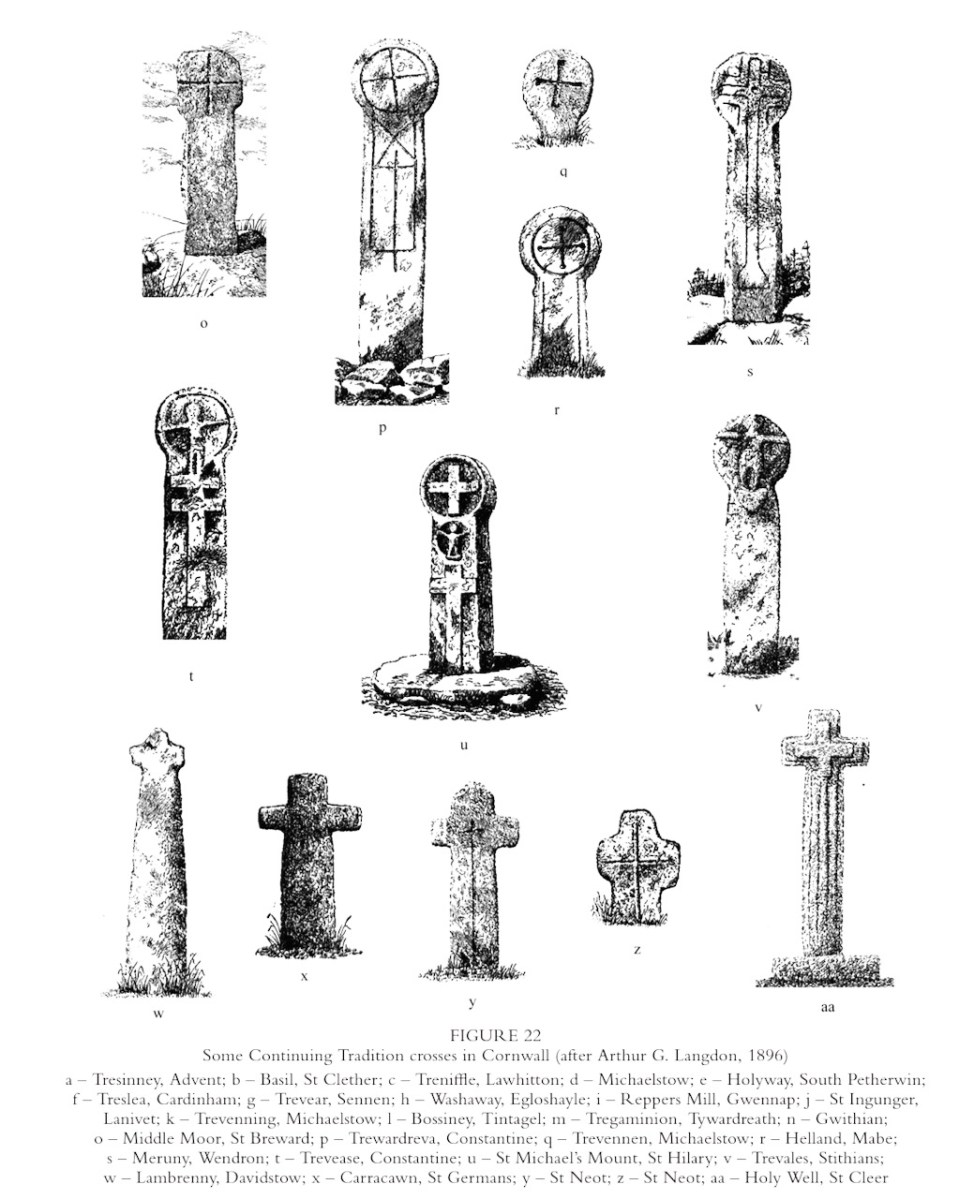

So – all of the evidence through association connects these crosses into a 12th century (or earlier), cross-carving tradition in Ireland. But Ó hÉailidhe also drew analogies with a group of very similar crosses from Cornwall, often referred to as ‘wheel-headed’. Their date? They were assigned to ‘very early Romanesque’ by Andrew Langdon, the authority on Cornish crosses over a century ago, and this assessment had been upheld by the august editors of the Corpus of Anglo Saxon Stone Sculpture in their 2015 Volume Early Cornish Sculpture. They state: The relationship of the Cornish sculpture to monuments in Wales, Ireland and Western Britain is of particular interest given Cornwall’s position as a peninsula jutting into the western seaways. In this context, the potential role of Scandinavian influence is considered against the absence of evidence for Scandinavian settlement in Cornwall.

Langdon’s illustration (above) will amply demonstrate how similar in form these crosses are both to the Fassaroe-type and to the Blackrock cross.

I will finish with a photograph of the Laughinstown Cross, behind its chain-link barrier in an under-developed park in a new housing estate. Behind me as I took this photograph is an equally beleaguered church (called Tully Church) of early medieval origins with associated graveyard. It is all but consumed by encroaching apartments, and clinging perilously to a cliff that is being dug out for yet more building. Although it’s clear we need more housing, it makes me sad that not more is being done to celebrate the heritage that still exists in this part of Dublin.