In 2019 I reported on the damage to the New Court Bridge and discussed why that was serious – the curious wall that we pass so often turned out to be a unique and important remnant of an eighteenth century designed landscape. The Good News is that the damage has been repaired, excellently, by Cork Co Council – this is what it looks like now (above).

This (below) is what it looked like in 2019. What follows is what I wrote then. T(he repair work was done in 2020 and I have been meaning to update the post since.)

New Court Bridge has been badly damaged recently. Why does that matter?

The damage from behind the wall. Now you can see that this is a bridge – but a most unusual one!

Most people driving by this dangerous bend, where the Ilen River meets the N71 just west of Skibbereen, notice the funny arches on top of the wall, but don’t think twice about them. It’s too risky to stop and take a close look, after all. Most people, in fact, probably don’t realise that they are driving over a bridge, although that’s a bit more obvious now as the County Council have put in one of those concrete pads that are going in front of all bridge walls at the moment (see lead photograph).

Water under the bridge

Does anyone know how the damage happened? Did a car take the bend too fast and hit the wall? Did the concrete work loosen the structure of the wall? Let us know if you have information. I hope nobody was hurt. All I know is that one morning I was driving into Skibbereen and there was a chunk of the wall – gone! [EDIT: Apparently a young and inexperienced driver took the bend too fast and hit the wall. He was not badly hurt, thank goodness.]

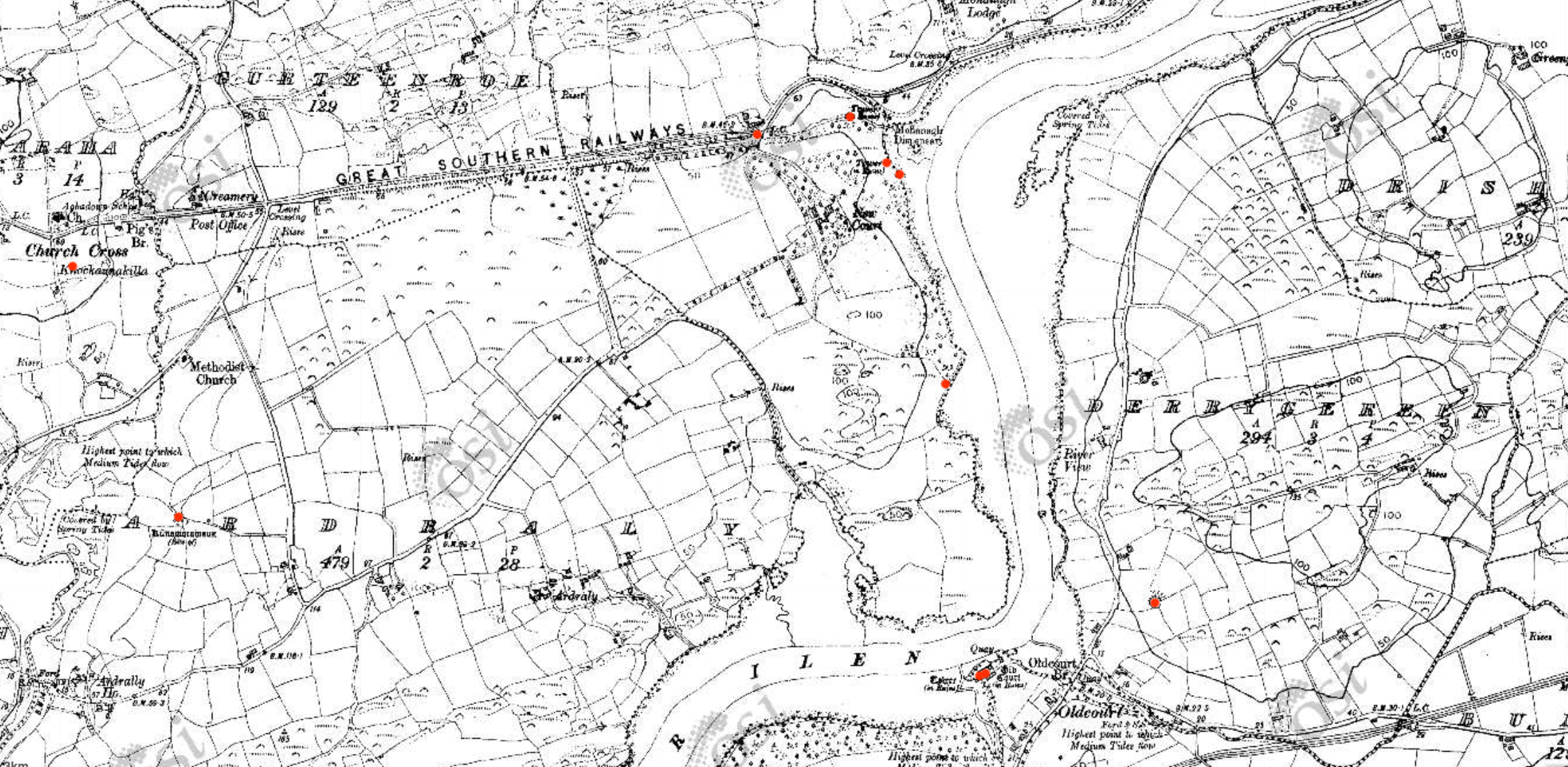

Early Ordnance Survey map of the New Court Estate, bounded by the Ilen River on the east and south. The red dots indicate the locations of the belvederes (marked as towers) and the bridge

We tend in Ireland to think of old estate walls like this one as ‘Famine Walls’, erected during the mid nineteenth century as work projects. But this wall was far older than that, and it hid a secret – an elaborate facade on the back with decorative arches and niches. It was part of the plan for a pleasure garden undertaken by Henry Tonson at his newly acquired ‘seat’ which he called New Court, to distinguish it from Old Court, across the river. Originally, there was a matching wall across the road, but it was demolished in a truck accident many years ago. EDIT: I misinterpreted this – rather than a matching wall across the road, in fact there were matching arches on either side of the road, west of the entry to New Court. Both are now gone, one at least due to the aforementioned truck accident. Thanks to Sean Norris for this information.

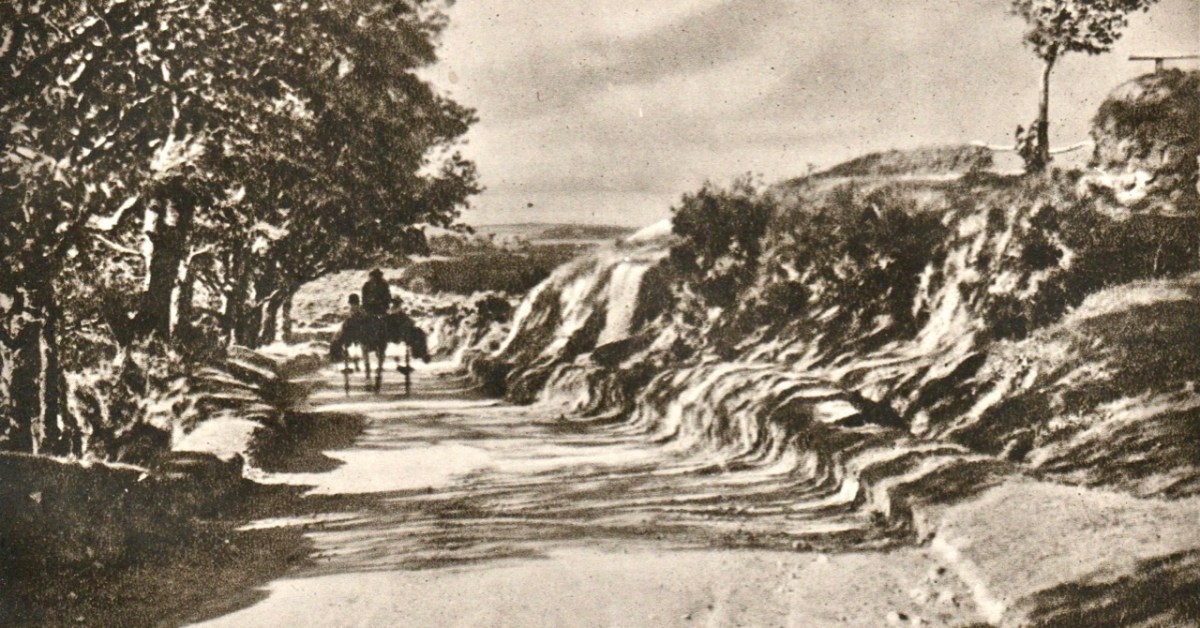

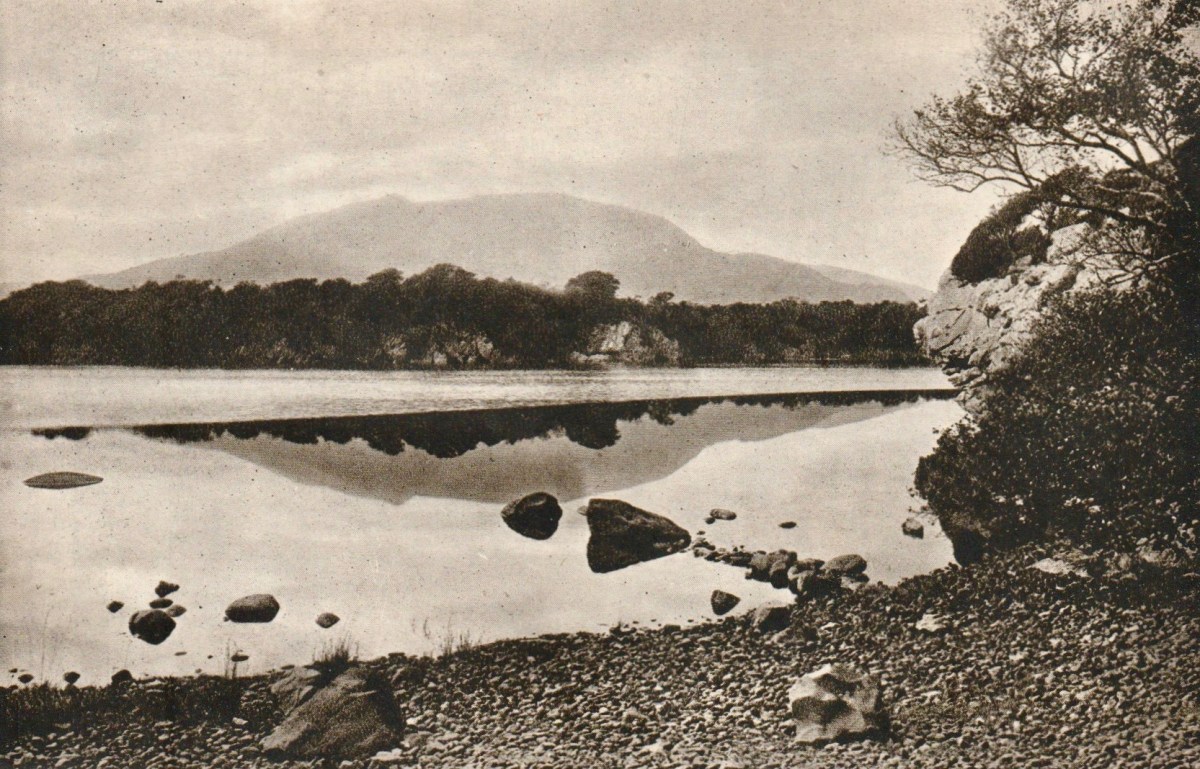

The Ilen floats by – a navigable river was a must for transporation to and from these early estates

The Tonsons had arrived in the 1660s. According to Burke’s Peerage, Major Richard Tonson received a grant of land in the county of Cork from Charles II for his distinguished exertions in favour of royalty during the Civil Wars and purchased the castle and lands of Spanish Island, in the same county. If he built anything on Spanish Island, just off Baltimore, no traces remain, and indeed, although strategic in marine terms at that time, it is hard to imagine how the island, mostly bare rock, would have made for comfortable accommodation.

The stump of one of the belvederes, overlooking the river

It appears he, or his son, Henry, bought the land on the west bank of the Ilen and Henry set about establishing his dwelling there. This included building the wall around the estate. Eventually, and we are not sure when, one of the Tonsons (over time they acquired a title, Lord Riversdale) developed the area around the house as a vast pleasure garden.

The most complete belvedere. This one also functioned as a dovecote

The fashion for designed landscapes is an eighteenth century phenomenon. As I said in my post on belvederes, in that century

. . . a different style of landscaping. . . dominated garden design in Britain, pioneered by William Kent and Charles Bridgeman and reaching its peak in the work of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown. The effect they strove for was naturalistic (as opposed to natural) – a planned layout that mirrored but enhanced their idea of a ‘wild’ and romantic landscape. Large expanses of grass, strategically placed lakes and ponds, plantings of carefully chosen tree and shrub species, and clever little structures such as temples, summer houses and belvederes all combined to delight the eye, create a romantic mood and, of course, attest to the taste and wealth of the owner.

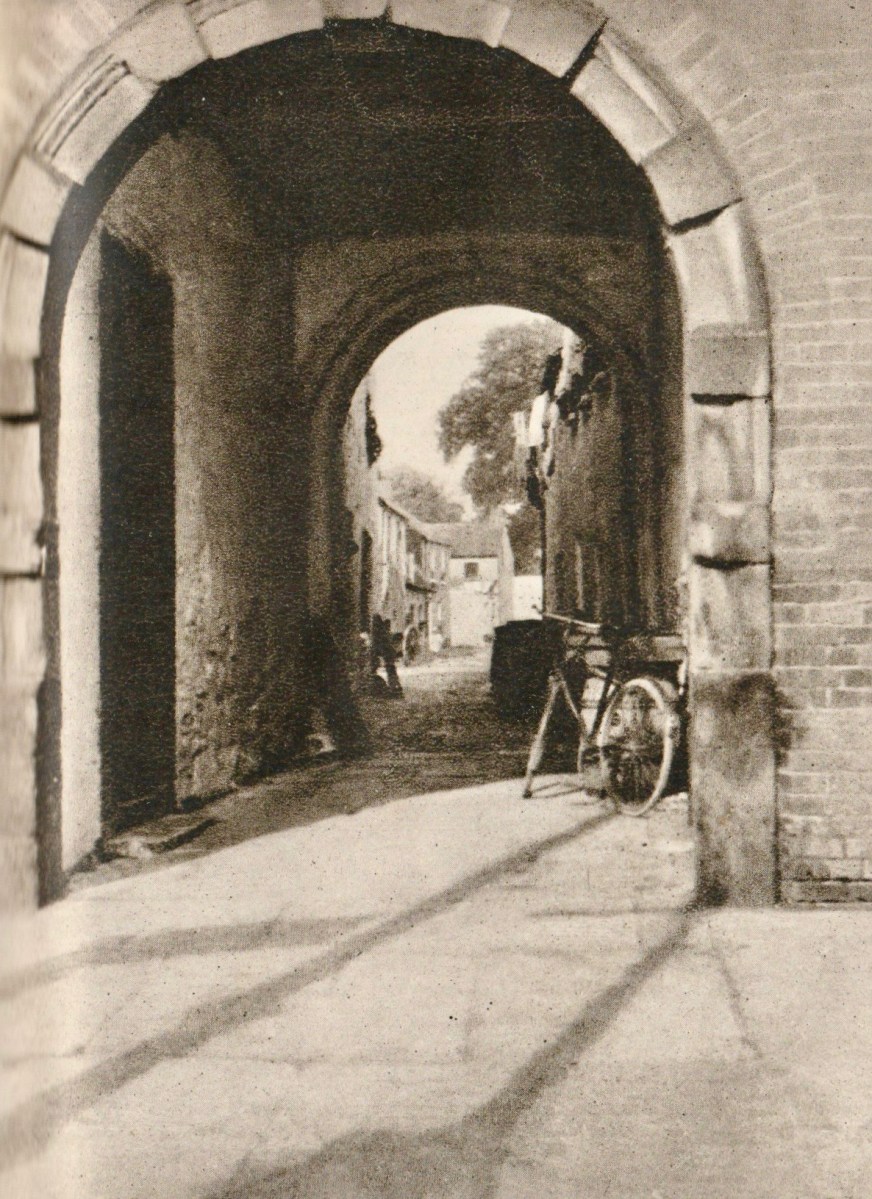

A closer look at the construction of the bridge. It would be fascinating to attempt a reconstruction drawing. The niches may well have held statuary or decorative urns

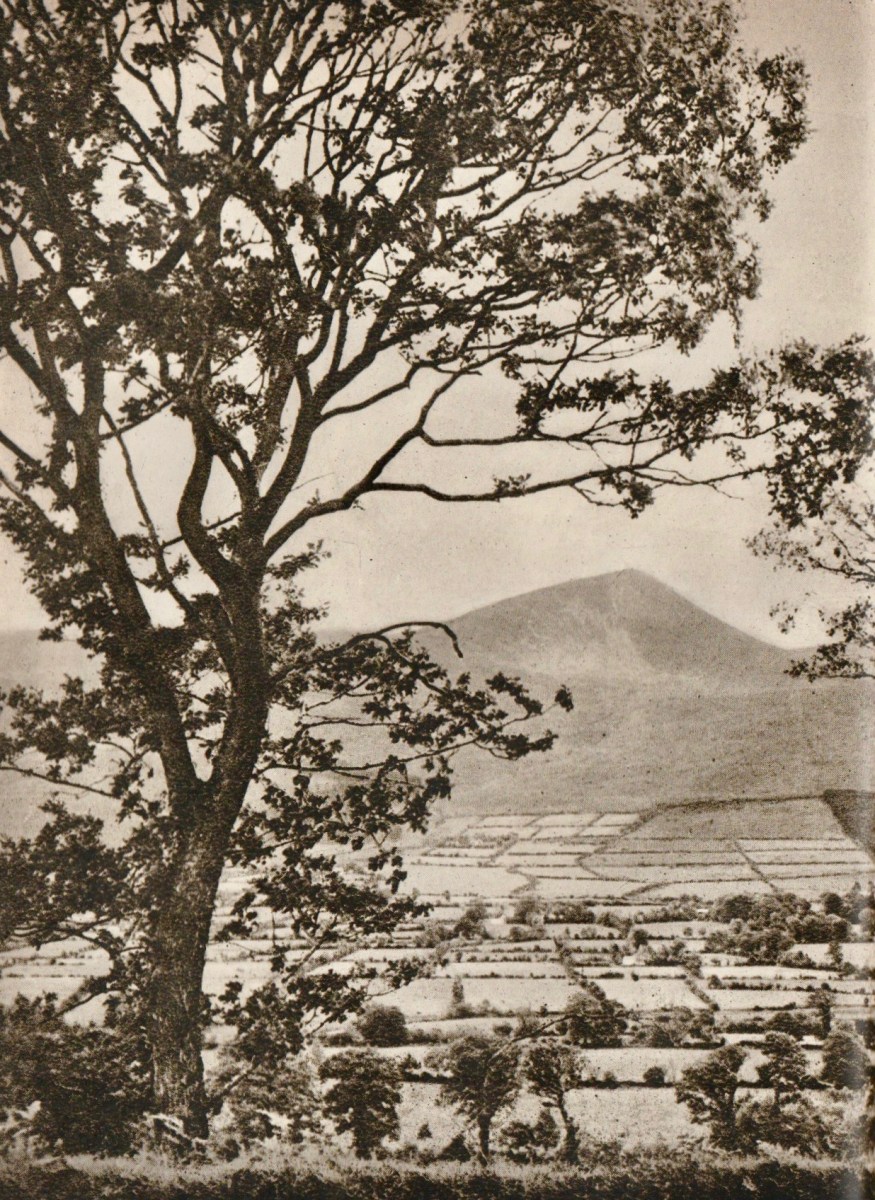

Although the grand houses at the centre of the estate have now gone (see this photograph in the National Library for a glimpse of the last one), there is lots of evidence still of such a designed landscape. Originally lawns sloped to the river – no need to build artificial ponds as the Ilen provided the perfect watery scene. Little round towers were built to be used as gazebos or belvederes (and in one case a dovecote): three in all, of which the stump of one and a fairly complete second are still to be seen. The bridge with its elaborate facing was the crowning glory of the estate wall.

The York House Water Gate as it would have looked originally on the Thames (Wiki Commons)

What did the bridge wall look like originally? We don’t know, but Peter Somerville-Large in his Coast of West Cork says it was modelled on the ‘water gates at Hampton Court’. I can’t find any images of this online, but I have found the water gate at York House, which is still there. It was built as a ceremonial landing place on the Thames (above) although it is now a long way from the river.

The York House Water Gate in an early photograph (www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/O18442 Credit, Royal Academy of Arts / Photographer William Strudwick )

Of course, it is larger and more elaborate, but you can still see the basic shape, with its curved arch on top and the arched niches in the wall. The arches at New Court may have been plastered, perhaps, or faced with some material. The York House Water Gate dates to 1626 and it’s all that left of the York House estate – the Tonsons may well have been familiar with it or with similar water gates along the Thames. Building such an edifice would have been aspirational, indicating a desire to impress.

This was what it looked like in 2016 – taken by a camera with spots on the lens

The likelihood, therefore, is that the bridge at New Court is most probably eighteenth century, and early eighteenth century at that – about three hundred years old. We don’t have a lot of structures in West Cork dating to then. Surely it’s worth preserving those that still exist? I am hopeful that the National Monuments Service (they’ve been alerted and have notified their Monument Protection Unit) will come riding to the rescue. I’ll be keeping an eye on it all – you do too. But note that this is private property, so no walking or driving through the gates without permission.

UPDATE, MARCH 20, 2019. This notice was received from the National Monuments Protection Unit: “Cork County Council (Bridge Management) have indicated it is prepared to repair the wall as a Reactive Maintenance Incident and will ensure repairs meet any necessary heritage requirements.”