Here’s a nutshell of what I have always known about the Anglo-Normans in West Cork (cheesy and improbable image above courtesy of ChatGPT – DALL·E). After they landed in Ireland in 1169, it took them about 50 years to get to West Cork. Once here, they established some castles or fortifications and intermarried with the local families. This state of affairs lasted until 1261, when a combined army of Irish, led by Fineen McCarthy, defeated them at the Battle of Callan driving them out of West Cork and destroying all their castles. For more on the Battle of Callan, see the post Sliding into Kerry, from 2017, by Robert.

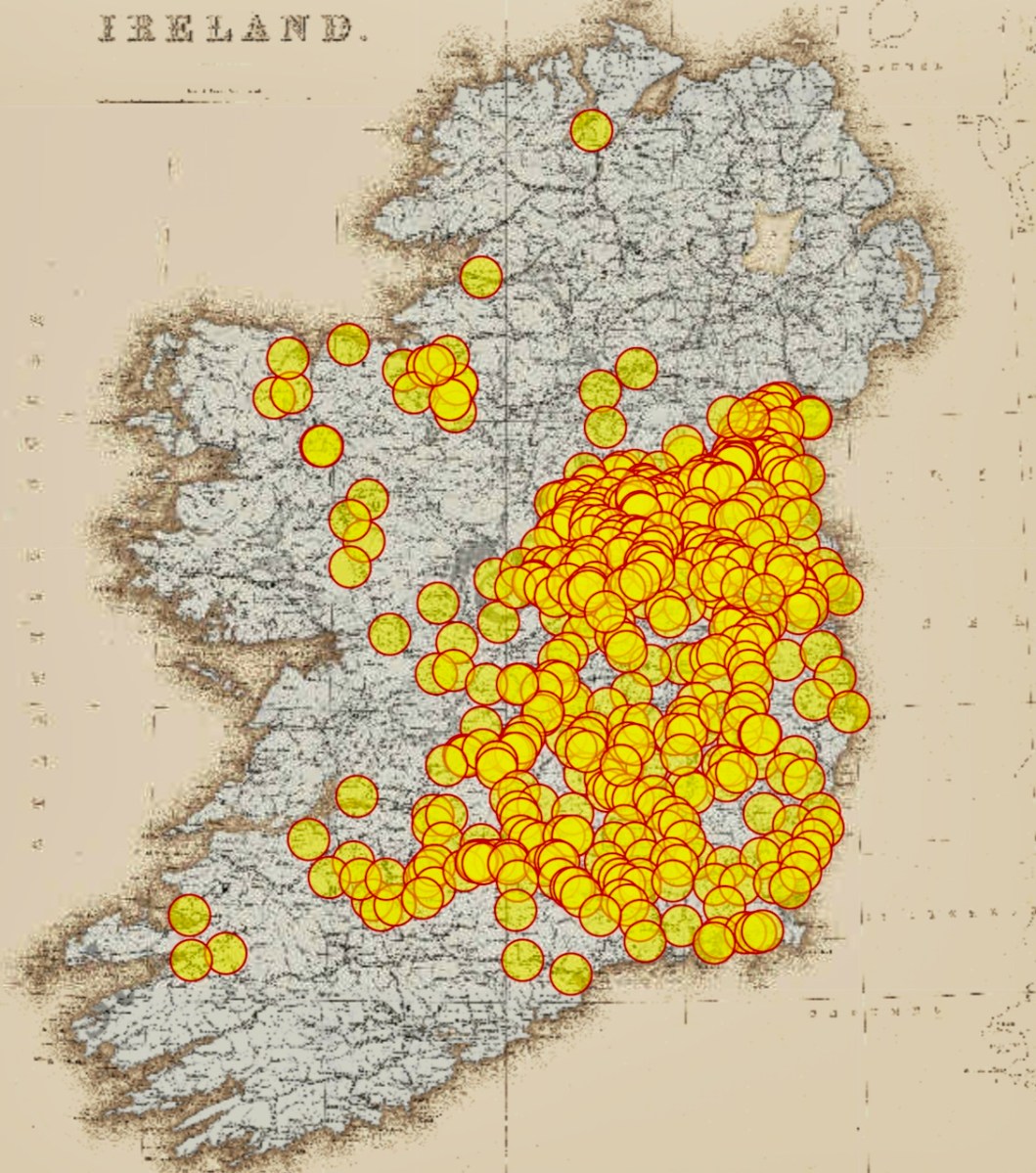

So is that why there is no trace to be found of the Anglo-Norman establishments in West Cork? In the rest of the country, at this early stage, they were mostly building motte and baileys, but there isn’t a single motte and bailey anywhere near West Cork – see the distribution map below, courtesy of National Monuments. And the masonry castles (or tower houses) we have were all built by the great Irish families. For a while I thought maybe Baltimore Castle was an Anglo-Norman building, but Eamonn Cotter has brought me up to speed on the excavation results and shown me it was much later.

There is quite a bit of documentary evidence of their presence, though, including references to their ‘castles’ so it has always been a surprise that west Cork is not littered with mottes or ruined towers. Even given the tradition that they were all destroyed after the Battle of Callan, it is impossible to imagine that a motte could be obliterated from the landscape. They were substantial earthworks, as can be seen from the brilliant JG O’Donoghue‘s reconstruction drawing below.

It turns out we have been looking but not seeing – with some exceptions, archaeologists have not recognised Anglo-Norman structures when they saw them. The most notable exception was Dermot Twohig (a contemporary of mine at UCC in the early 70s) who, as early as 1978 described Norman ringworks in Cork. In the Bulletin of the Group for Irish Historical Settlement for 1978, buried within an annual conference report, Twohig reports:

Although I have not succeeded in inspecting, on the ground, all of the early Norman castles in Co. Cork, three of the sites I have examined – Dunamark (Dun na mBarc), Castleventry (Caislen na Gide) and Castlemore Barrett (Mourne/Ballynamona), can be classified as ring-work castles. Dunamark is one of the best examples of a ring-work I have seen in either Britain or Ireland. Castlemore Barrett had a hall-keep built within the ring-work c.1250, to which a tower-house was added in the fifteenth-century. Castleventry may have had a stone built gate-tower similar to the one at Castletobin, Co. Kilkenny. . . Further field-work and excavation will, I believe, demonstrate that the ring-work castles constituted a very significant element of fortification in the Norman conquest of Ireland.

I don’t know what happened, but Dermot’s analysis does not appear to have become part of what students were taught at UCC. Those students in turn became the mainstay of the Archaeological survey of the 1980s and they labelled Dunnamark (i’m using the OS spelling) a cliff-edge fort and Castleventry a ringfort.

In fact, the very term ringwork (or ring-work, or ringwork castle) seems to have become an archaeological football, with some scholars asserting that we have no useful definition of its distinctive features and most of them are probably just ringforts, while others have championed the use of the term and tried to bring clarity to the debate.* in the heel of the hunt, it now seems likely that ringworks were indeed part of the system of land-claiming exercised by the Anglo-Normans, that they were usually larger and more solidly built than ringforts, and located strategically – near water or with commanding views. As you can see from the photograph below, the Castleventry banks are high, and were originally stone-faced.

In the course of 2023 and early 2024 Robert and I visited four locations with Con Manning, retired archaeologist with the National Monument Service and a recognised authority on Irish medieval archaeology. Con has now written about the four sites in the latest issue of Archaeology Ireland, naming them as Angle-Norman ringworks. The first is Castleventry, to which we were brought by local historians Dan O’Leary and Sean O’Donovan, and I wrote about our visit to that that one here. So go back now and read what we found there and how intrigued Con was by what he saw. This was the site that set him off on his investigations.

The description of this site in the National Monuments record is as follows:

In pasture, atop knoll on E-facing slope. Circular, slightly raised area (32.6m N-S; 34.5m E-W) enclosed by two earthen banks, stone faced in parts, with intervening fosse. Break in inner bank to W, now blocked up; modern steps to E. Outer bank broken to W (Wth 3.5m), blocked up; S gap leads to laneway; modern break to NNW. Church (CO134-025004-), graveyard (CO134-025003-) and souterrain (CO134-025002-) in interior; second souterrain (CO134-089—) beside outer bank to E.

Recognising that not all readers have access to Archaeology Ireland, and with Con’s permission, I will tell you that he notes that after the Battle of Callan

in that same year many of the castles of the colonists for burnt or destroyed. Two were mentioned in a single entry in the Annals of Inisfallen as follows: “the castle of Dún na mBarc, and Caislén na Gide also, were burned by Mac Carthaig and by the Desmumu.”. Caislén na Gide has been identified as Caisleán na Gaoithe or Castleventry. . . No likely site for this clearly important castle has to date been identified on the ground.

After more information on the history of the site and its association with the Barrett and the Barry families, Con concludes, I have no doubt but that this monument is the castle of Castleventry, a substantial and impressive ringwork reusing an older ringfort.

Next week I will write about the other three sites (spoiler alert – one of them will be familiar to regular readers already) and come to conclusions about the evidence we’ve been missing for the presence of the Anglo-Normans in West Cork.

* I applaud particularly the work of Grace Dennis-Toone, Her thesis brings considerable rigour and analysis to the topic. When is a ringwork a ringwork? Identifying the ringwork castles of County Wexford with a view to reconsidering Irish ringwork classification.