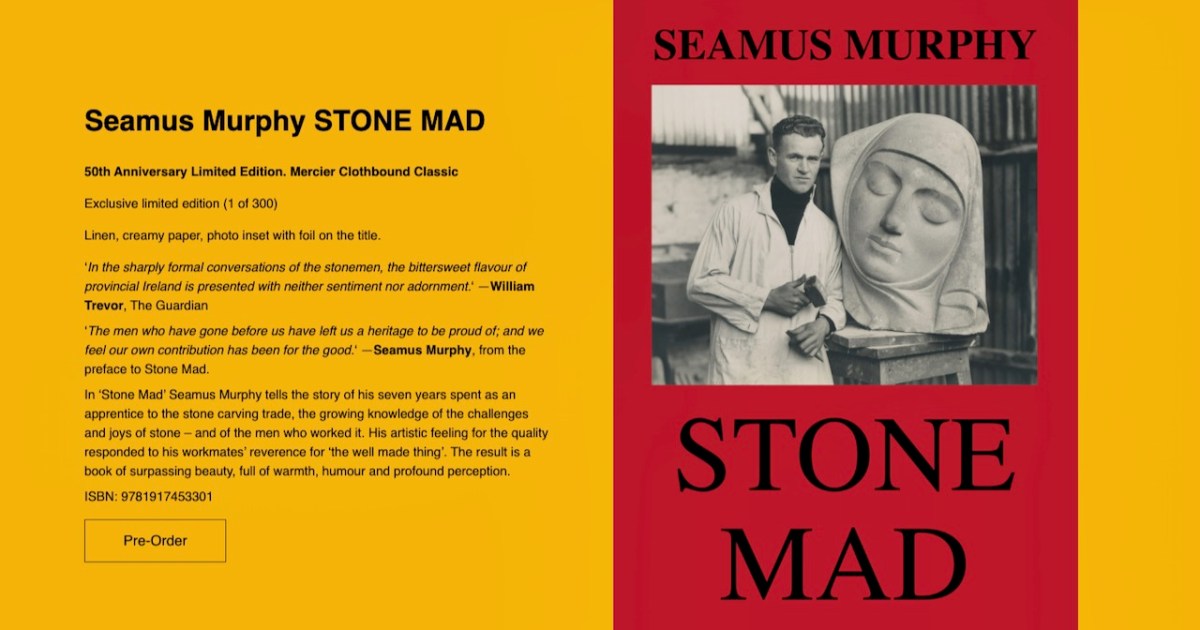

Yesterday, in a ceremony in the Cork Public Museum, Mercier Press launched a re-issued Stone Mad, by Seamus Murphy. This year is the 50th anniversary of Seamus’s death, in 1975. The book is also the One City One Book choice of the Cork City Library, as part of the 2025 Cork World Book Fest taking place all this week in venues across Cork.

I attended the launch in the Museum, in Fitzgerald Park, home of several sculptures by Seamus, including this one of De Valera, above. Long-time readers will remember our own Rock Art Exhibition in the same building ten years ago – somehow apt that it featured the prehistoric version of the stone carving tradition we were celebrating yesterday.

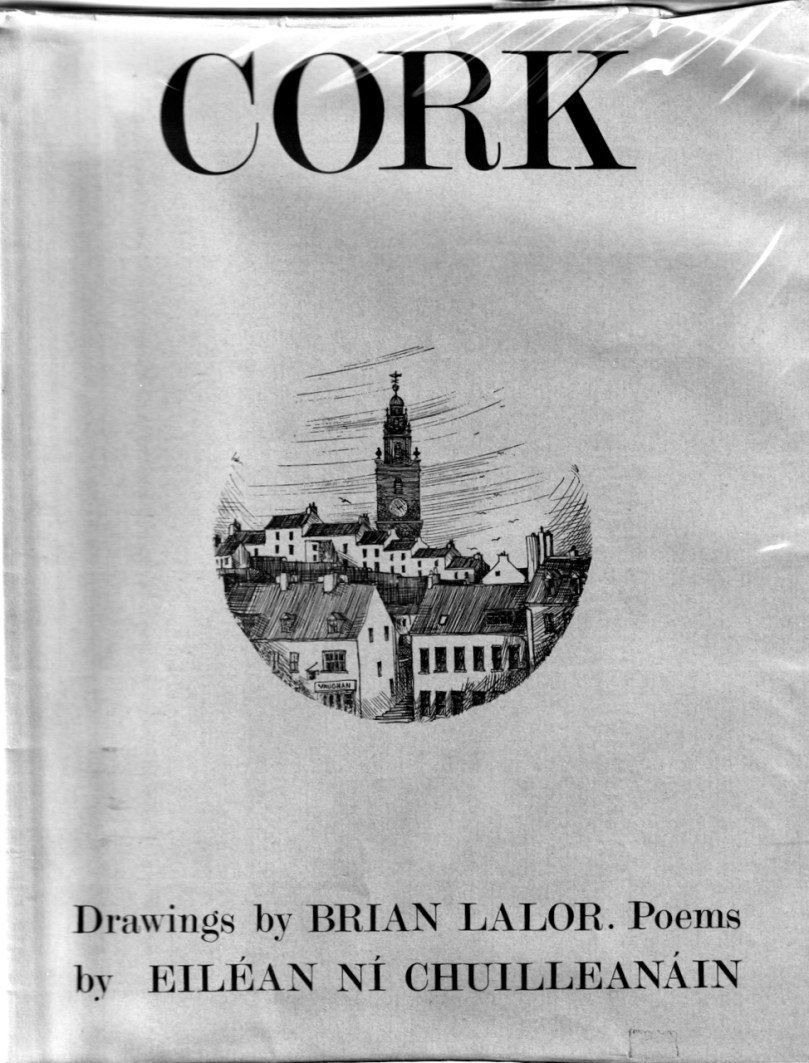

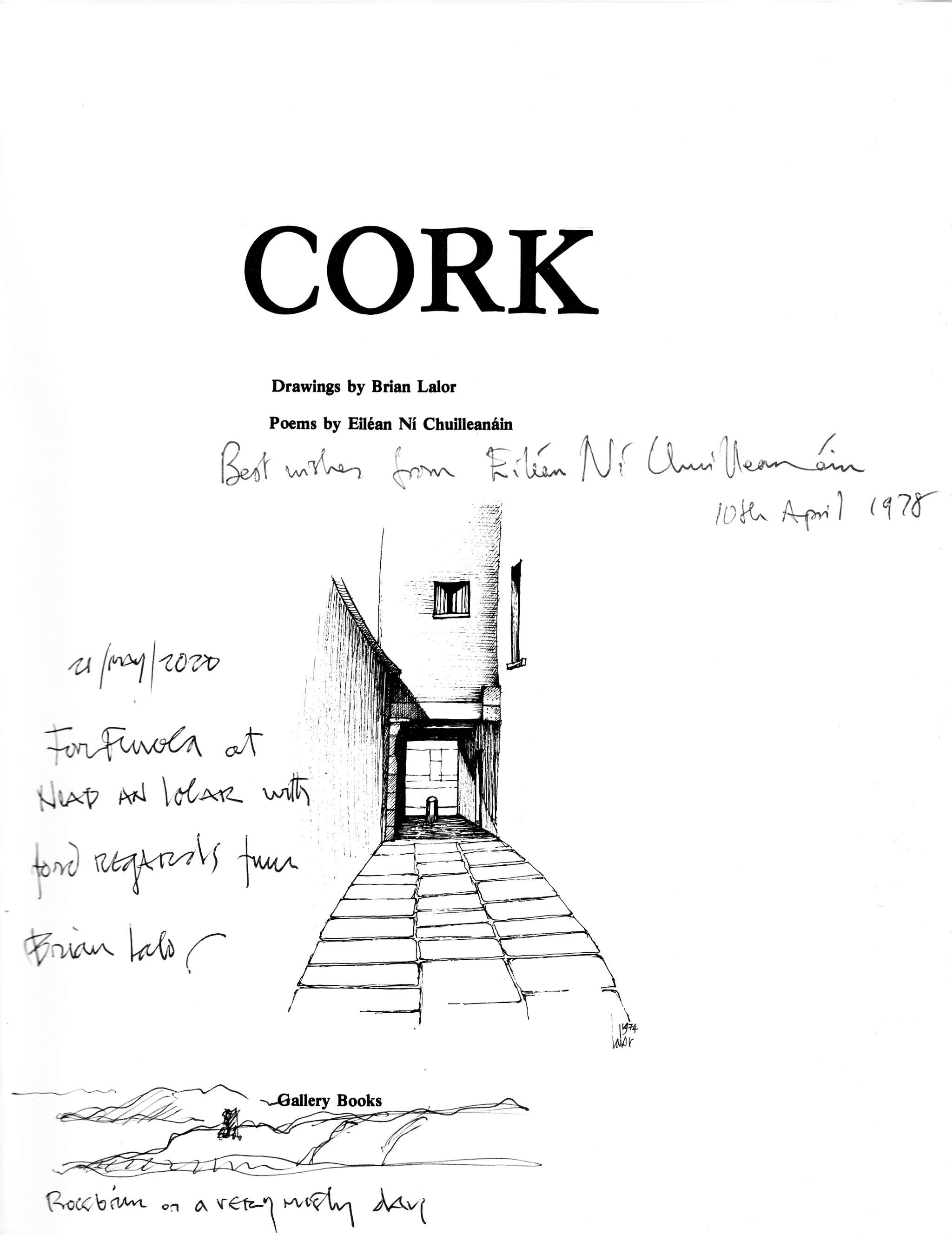

The book was officially launched by the poet Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, about whom I wrote here. She had known him in the old days in Cork, and her’s was a wonderful, evocative, beautifully written summary of Seamus and his book. She finished with words that resonated with everyone in the room (and it was packed!) – I paraphrase it as: Read this book again. And afterwards, go and wander around Cork. You will never look at it the same way again.

Eoghan Daltun, author of An Irish Atlantic Rain Forest, was there too. Besides a passionate conservationist, he is a skilled sculptural restorer, and was responsible from rescuing Dreamline from weather and lichen damage a couple of years ago. Standing within the display of carvings and tools and images, all carefully set up by the Museum team led by Curator Dan Breen, Eoghan talked us through what was involved in carving in stone and, many years later, restoring the artwork.

I was also very pleased to meet Ken Thompson, the stone carver who finished off lettering on Seamus’s headstones, after his death, and who carved many monuments I have encountered in Cork and elsewhere, including the inspirational memorial to the Victims of the Air India tragedy in Ahakista, below.

Seamus Murphy is acknowledged as one of Ireland’s best stone carvers, and an icon of the 20th century Cork cultural scene. His work can be seen all over Ireland, but especially in an around Cork. If you are not that familiar with his output, the documentary Seamus Murphy A Quiet Revolution is a great introduction to his life and work.

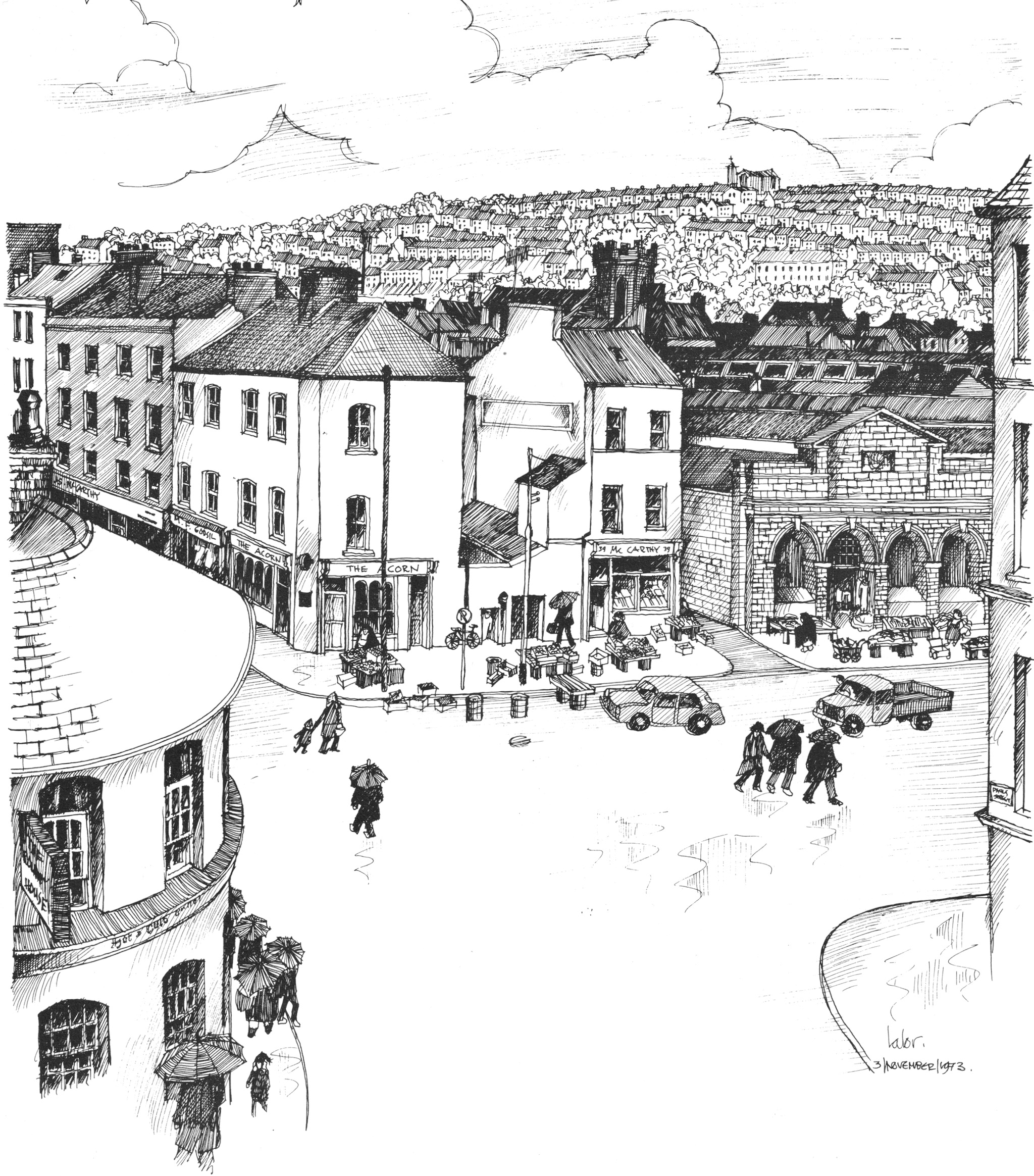

Stone Mad has been a favourite on our shelves as long as Robert and I have had a joint library. We own a couple of copies, including a hardback of the second edition, signed by Seamus and with illustrations by William Harrington. It’s an evocative summation of his life as a ‘stoney’, the men with whom he worked, and the craft they honed together. It has become iconic, as much for its on-the-ground and entertaining picture of life in a Cork stone yard as for its musings on stone carving as an art, from medieval times to the present day. For some extracts, see my post, Building a Stone Wall.

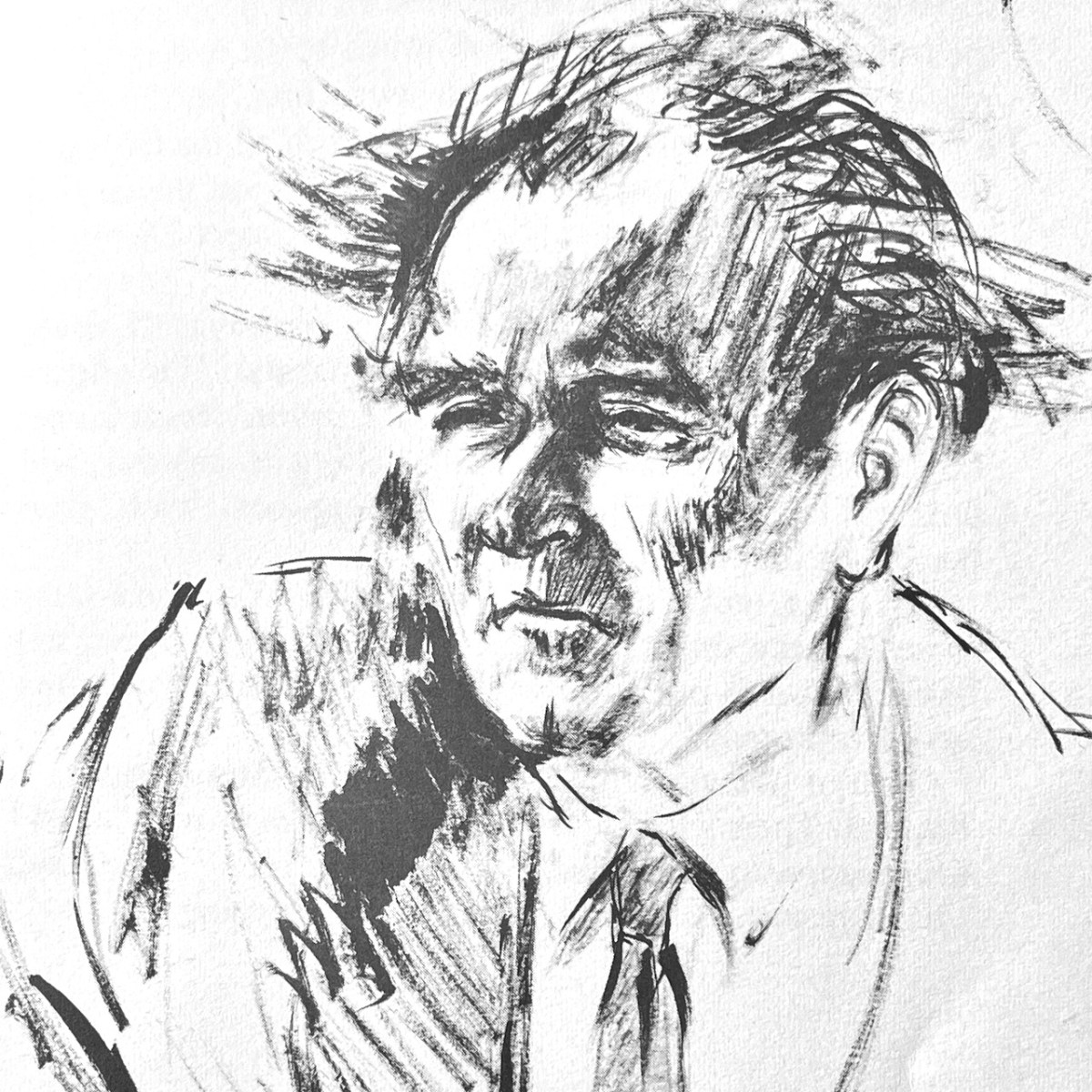

The illustrations by William Harrington, pen and ink sketches, capture the work, the camaraderie of pub life after a hard day’s work, but also includes a sensitively drawn portrait of Seamus.

If you don’t have a copy of Stone Mad, do get one – it deserves a place in your library. I will leave the last word to Ken Thompson, from the documentary I link to above. Ken inherited Seamus’s tools (below) – most of them look surprisingly delicate for the work they do, don’t they?

Ken says, Now he’s been dead for 40 years, but I see his work in churches all the time. His work is shining out. It’s still a beacon. It still speaks.