If you read my post last week you will recognise this autumnal view of Rossbrin Castle. I took the photo in November 2017 and looked it out after I watched the magic of a skein of wild geese flying over Nead an Iolair just a few days ago – at the end of August. There’s something wistful about that spectacle – birds coming to winter on our west coasts – and Irish weather lore has to be heeded about these early advents:

It was generally believed that the early arrival of wild geese meant that a prolonged and severe winter was in store. This is a very old belief, as the ninth-century Irish work ‘Cormac’s Glossary’ states that the brent goose usually arrived at the coasts of Erris and Umhall between 15 October and 15 November, and that when it appeared earlier, it brought storms and high winds. Similarly, in Counties Donegal and Galway, when the wild geese arrived, it was a sign that cold and frosty weather was on the way. In Donegal, a sign of an approaching wind was when a goose stuck its neck up into the air and beat its wings against its stomach. Fishermen would watch out for this and if they saw it would not go out, believing that a storm was on the way . . .

(Niall Mac Coitir – Ireland’s Birds: Myths, Legends and Folklore, Collins Press 2015)

Today’s post – while inspired by my sighting of the wild geese – is more connected to swans: these large and graceful birds are a constant down on Rossbrin Cove, and plentiful along our West Cork coastlines. Niall Mac Coitir also has much to say about them:

In Ireland it was generally believed to be very unlucky to kill a swan, and many tales were told of the dire consequences for those who did so. For example, the mysterious death of one of their farm animals often occurred soon afterwards. In County Mayo the whooper swan was never interfered with, on account of a tradition that the souls of virgins, who whilst living had been remarkable for the purity of their lives, were after death enshrined in the form of these birds . . . In Donegal it was believed that swans were people under enchantment, so that bad luck would come to anyone who interfered with them . . .

(Ibid)

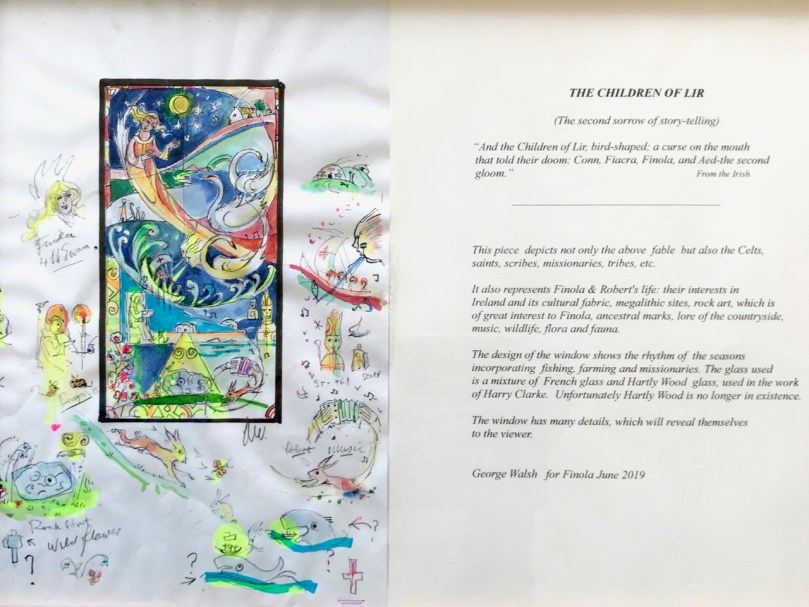

We know all about the tradition of people being turned into swans from the legendary Children of Lir – one of whom was Finola: you may remember the stained glass window we have in our house. A few years ago I found the above book in the wonderful Time Traveller’s Bookshop in Skibbereen (which has now transformed itself into the Antiquity Bookshop Café, the first all-vegan Cafe in West Cork: it’s well worth a visit – for books and food!). I was attracted initially by the cover and the illustrations, and then was delighted to find that the first story in the book was all about Finola and is a modern ‘take’ on the Irish legend. I had to buy the book, of course, for our Finola and I immediately thought of ‘The Wild Swans’ when I saw those wild geese. This post results from those wandering encounters.

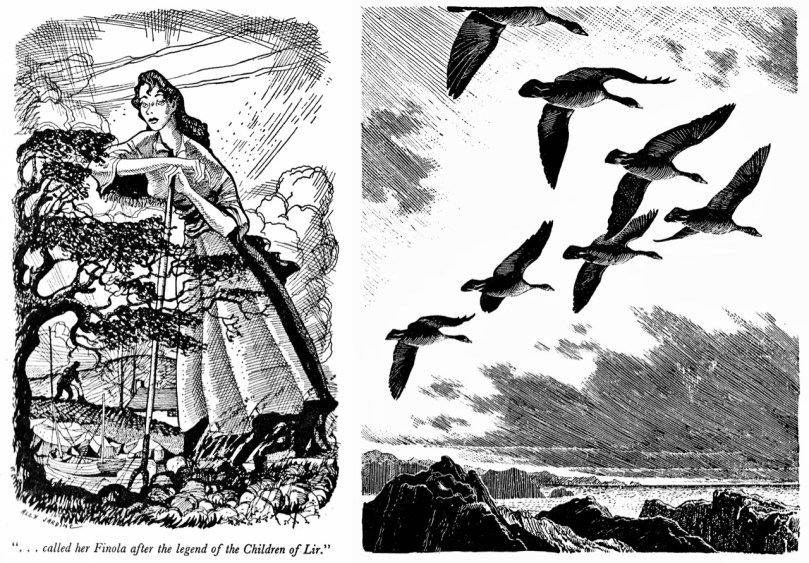

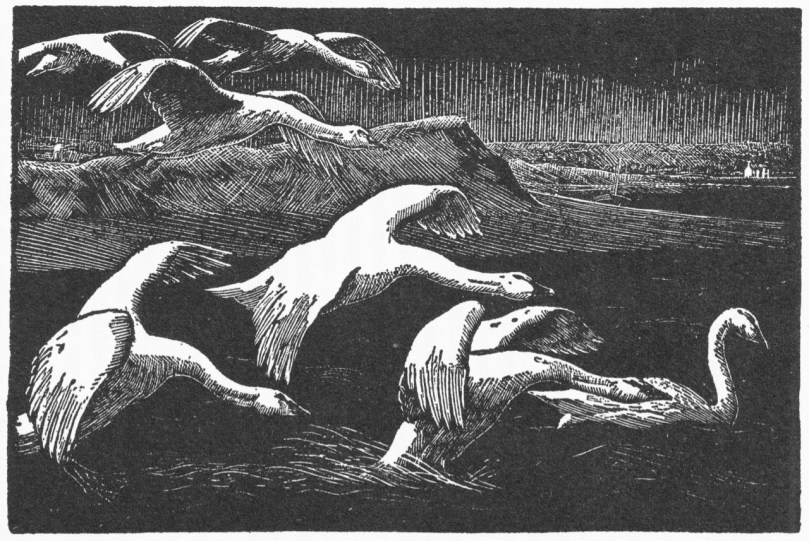

Another of the illustrations from The Wild Swans – used on the cover: do you see the swans? The second picture above – of the four swans – is also from the book. The illustrator is Alex Jardine, about whom I have been able to find very little, other than he was British, lived from 1913 to 1987, wrote and illustrated books on angling, and designed a number of postage stamps. I was also keen to find out more about the author of this book – Ethel Mannin (shown above next to the book cover) – and initially came across scant information, until I discovered a connection with W B Yeats. Then, by dipping and diving through letters and articles specifically by and about Yeats, I was able to put together some often surprising details on her life.

Above left – Alex Jardine’s illustration for The Wild Swans showing Finola – beautifully detailed and with intriguingly distorted perspective (suitable for a ‘modern’ legend?); above right – for comparison, an illustration from the same period (1950s) of wild geese by prolific British illustrator Charles Tunnicliffe: a scene which looks uncannily like a peninsula from the west coast of Ireland

Ethel Mannin was born in 1900 in London, and died in 1984. None of her writings is in print today and she is now little regarded, yet in her lifetime she wrote and had published well over a hundred volumes, half of which were novels and others which included short stories, children’s books, travel books, autobiographies and works on literature, politics and her contemporary world. On the fly-leaf to The Wild Swans – published in 1952 – is the statement:

Her reputation as a writer is founded on her honesty and unorthodoxy. For some years past she has done most of her writing in retreat in a cottage in the remotest west of Ireland, the country of her ancestors . . .

Mannin traced her family background to the O’Mainnin owners of Melough Castle, Co Galway. In 1940 she settled close to Mannin Bay in Connemara, renting a cottage which she eventually bought in 1945. She spoke at public meetings against the Partition of Ireland – ‘the imperialist problem nearest home’ – and was elected Chairman of the West London Anti-Partition Committee. Her travels included India (where she attended a World Pacifist Conference and tore up her diary en route, throwing it overboard in the Indian Ocean, and found Hinduism repellent ‘with its lingam cult’), Burma, Morocco, Sweden, the Soviet Union, Brittany, where she befriended Cartier-Bresson.

I found more wild swans in this illustration by Charles Tunnicliffe from the 1927 best-seller and Hawthornden Prize winner Tarka the Otter: His Joyful Water-Life and Death in the Country of the Two Rivers by nature writer Henry Williamson. Tarka captured the public imagination and has never been out of print, even though Williamson himself became unpopular following his support for Oswald Mosley and fascism

Ethel Mannin met W B Yeats in the 1930s and they became lovers. Their relationship was reported by Brenda Maddox in Yeats’s Ghosts: The Secret Life of W B Yeats, Harper Collins 1999:

Ethel Mannin was a rationalist and skeptical, he mystical and credulous. Politics divided them too. She was left-wing, just short of being a Marxist, and had recently returned starry-eyed from the Soviet Union; his leanings were firmly the other way. But that hardly mattered when, as a companion, she was brilliant, fun, and full of the salty talk that Yeats adored. She was not worried about his cultural baggage: “Yeats full of Burgundy and racy reminiscence was Yeats released from the Celtic Twilight and treading the antic hay with abundant zest.”

In 2014, to mark the 75th anniversary of Yeats’ death, Jonathan deBurca Butler wrote in the Irish Independent newspaper an article titled The Many Women of W B Yeats. This is an extract:

In 1934, Yeats, who had been suffering from both sexual and artistic impotence for three years, had a Steinach operation, a type of vasectomy, which was said by its supporters to increase energy and sexual vigour in men. According to Yeats, the procedure worked and he claimed to go through what he called “a second puberty”. Shortly after the operation, Ethel Mannin, a 34-year-old writer and member of the World League for Sexual Reform, was called on to “test the operation’s efficacy”. The test was by all accounts unsuccessful but it showed Yeats was still inclined towards trying his hand. If all else failed he could still arouse his mind . . .

This ‘swans’ illustration is almost exactly contemporary with Ethel Mannin’s The Wild Swans. Robert Gibbings wrote and beautifully illustrated Sweet Cork Of Thee, which was published by J M Dent in 1951

Ethel Mannin married twice, and had one daughter, Jean, after which ‘ . . .she espoused the idea that a masculine mind better suited women writers than motherhood . . . ‘ Apart from W B Yeats she also had an affair with Bertrand Russell. In her later years, Ethel returned to England and lived out her life in Devon – also, incidentally, the home of Henry Williamson. I have been chasing the works of Ethel Mannin, and have succeeded in recently locating some very inexpensive used copies on the internet – including some of her biographical works. Once I have these I may have more to report on her connections with Ireland. Meanwhile, I can only recommend The Wild Swans for its romanticism and imagination – and its seductive illustrations. And, of course, for its connections with Finola!

Because of the Yeats connection, it seems appropriate to quote his poem The Wild Swans at Coole (1916):

The trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky;

Upon the brimming water among the stones

Are nine-and-fifty swans.

The nineteenth autumn has come upon me

Since I first made my count;

I saw, before I had well finished,

All suddenly mount

And scatter wheeling in great broken rings

Upon their clamorous wings.

I have looked upon those brilliant creatures,

And now my heart is sore.

All’s changed since I, hearing at twilight,

The first time on this shore,

The bell-beat of their wings above my head,

Trod with a lighter tread.

Unwearied still, lover by lover,

They paddle in the cold

Companionable streams or climb the air;

Their hearts have not grown old;

Passion or conquest, wander where they will,

Attend upon them still.

But now they drift on the still water,

Mysterious, beautiful;

Among what rushes will they build,

By what lake’s edge or pool

Delight men’s eyes when I awake some day

To find they have flown away?