It was a big day in Ballvourney yesterday: the public unveiling of two replicas of the 800 year old wooden figure that has been central to observances of St Gobnait on her day for as long as anyone can remember – we must be talking centuries! If you are not familiar with St Gobnait – or her celebrations – read my post here.

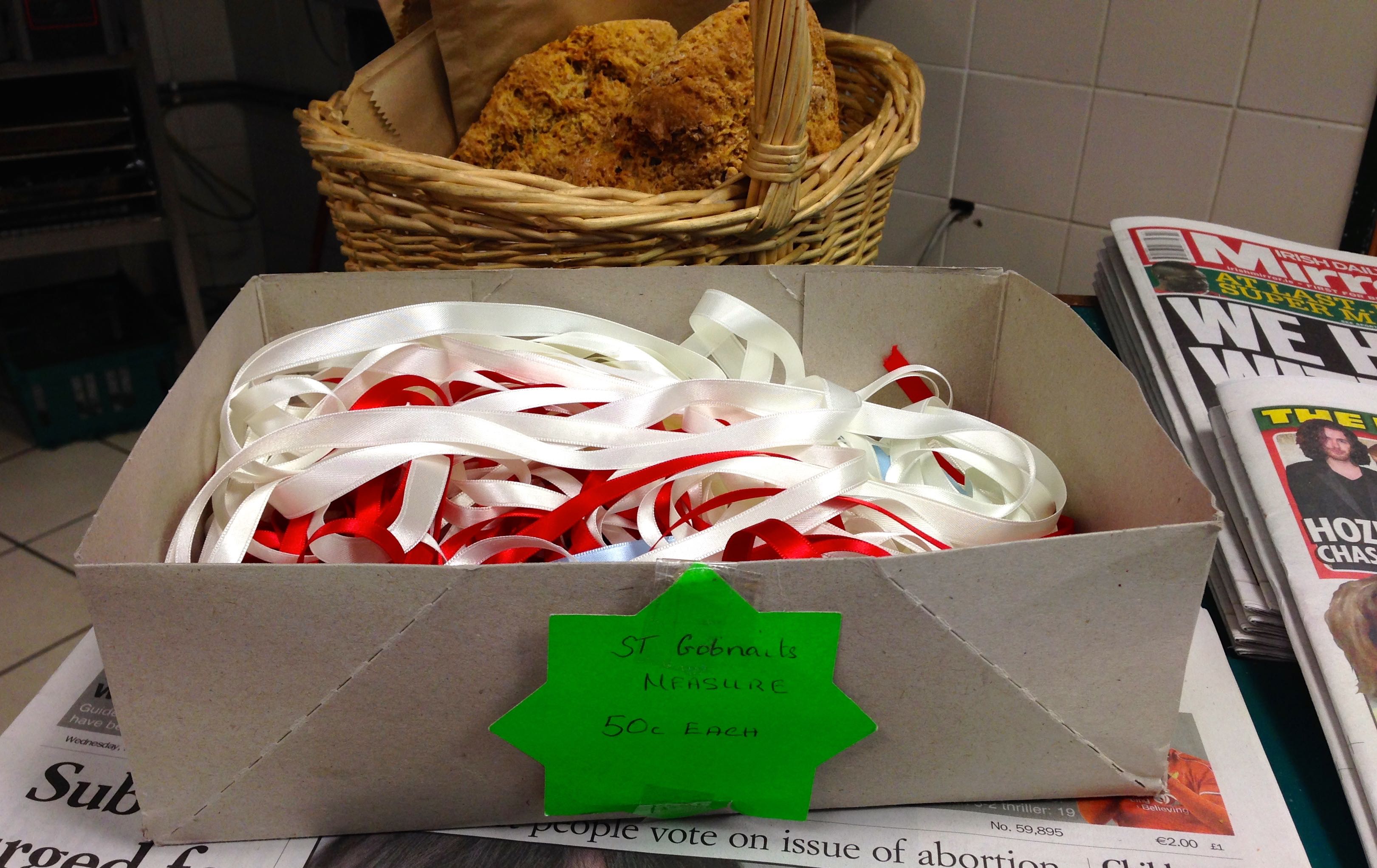

It’s actually St Gobnait’s Day today: the eleventh of February. As I write this, the congregation in the saint’s church will be venerating the 13th century wooden figure by ‘measuring’ her with ribbons. But also, for the first time, they will be able to view the two copies of that figure which have been made over the last few months. That exercise has been undertaken so that the figure itself could be fully studied because it is of great historical interest. There are other medieval carved wooden figures of saints surviving elsewhere in Ireland, but this is the only one that is still in regular active use.

. . . A medieval wooden image of Gobnait, kept traditionally in a drawer in the church during the year, is venerated in the parish church on this day. The devotion is known as the tomhas Gobnatan . People bring a ribbon with them and ‘measure’ the statue from top to bottom and around its circumference. This ribbon is then brought home and is used when people get sick or for some special blessing. The statue is thought to belong to the 13th c. A second pattern in honour of Gobnait was traditionally celebrated in Baile Bhúirne at Whit . . .

The above citation is taken from The Diocese of Kerry website, which sets out a comprehensive review of the saint and the activities which honour her. Here’s the measuring taking place a few years ago:

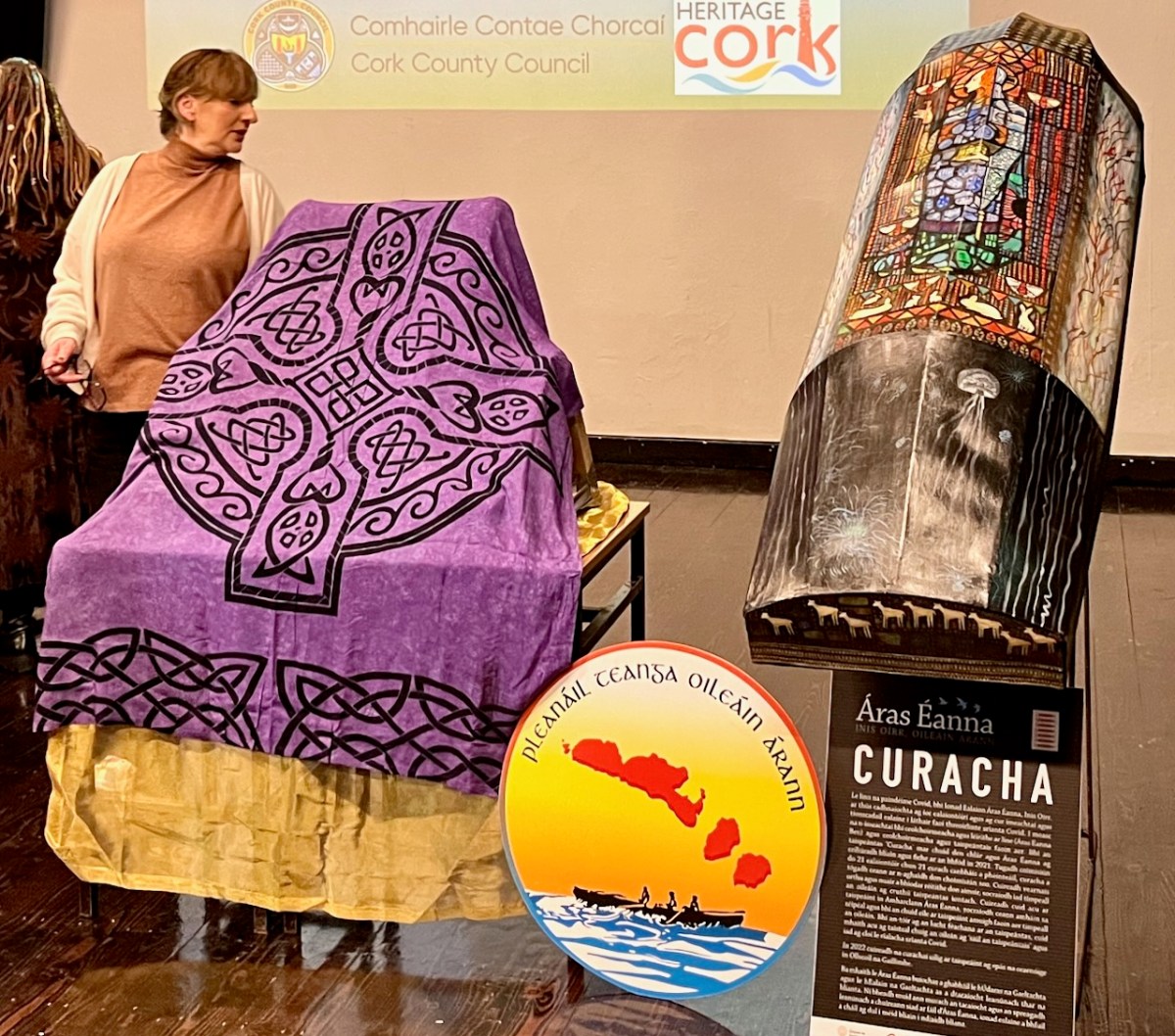

National Heritage Week 2023 explains the purpose of the project to replicate the carving:

. . . As patron saint of the parish, the statue provides a tangible link to the saint but importantly represents the long-standing living devotion to Gobnait. The wooden figure carved out of oak clearly depicts a female monastic. It was guarded over the centuries by the O’Herlihy clan, who were the ruling Gaelic lords of the Ballyvourney area during the medieval and late-medieval periods. It remained in the safe-keeping of members of the O’Herlihy family until they handed it over to the local parish priest in the late-19th century and it has been protected and kept secure by the Ballyvourney Church Committee ever since. The 3D project will comprise the digital scanning of the statue which in turn will enable a 3D generated wooden print out. A second replica will be hand carved as an integrative representation of how the statue would have looked originally before the centuries aged and tarnished it. The replicas will then be placed permanently on display in the Parish Church with information signage . . .

St Gobnait in 3D

Above is a view of the original carving (in the centre) with the replica of that on the right. On the left is the ‘integrative representation’ – that is the carver’s interpretation of what the figure might have looked like when she first saw the light of day in the 1300s. On the left is Bishop William Crean – Bishop of Cloyne since 2013: he presided over the unveiling of the two replicas yesterday. On the right is John Hayes, of Special Branch Carvers in Fenor, Co Waterford. He was responsible for the carving project and has made an excellent job!

John gave us a presentation yesterday, after the unveiling ceremony, and we learned how he closely examined the original statue, taking detailed measurements and a full photographic survey. This enabled a Sketchfab 3D rendering to be produced: this became the basis for his work. During the examination he was able to find traces of paint, which enabled him to render the interpretative version with – very likely – a high degree of fidelity to the original.

I got the chance to talk to John and ask him about the timbers used for the original and the replicas. The original is of oak, and we don’t have a way of knowing where this came from. The replicas are of ash: this is a good material for stability and longevity. John had access to a good source of seasoned wood.

The day was a study day for St Gobnait, and encompassed a whole lot more than the unveiling of the replicas (they are waiting under the cloth- above – to be revealed)! Note the currach in the pic also: that’s another project – to establish a Camino tracing the route which Gobnait took as she travelled around Ireland from the Co Galway Aran Island of Inisheer, having been told by an angel that her life would be fulfilled when she saw nine white deer. She spent time in Dun Chaoin and Kilgobinet in Kerry, Ballyagran in Limerick, Kilgobinet in Waterford, and Abbeyswell and Clondrohid in Cork, before finally finding the deer in Ballyvourney. You can see those deer on the stern of the currach, above. There are at least eight holy wells in Ireland dedicated to the saint. Amanda has written extensively about Gobnait’s travels and – of course – about her wells.

There was also an excellent series of talks about Gobnait. Events took place in Ionad Cultúrtha an Dochtúir Ó Loinsigh, which is a great facility in the community. Here we are – together with our good friends Peter and Amanda (you have met them frequently on the pages of this Journal), - waiting for proceedings to begin:

This is the moment of unveiling: the Bishop is accompanied by the Parish Priest – Very Reverend John McCarthy SP – and archaeologist Dr Connie Kelleher, National Monuments Service: she has played a significant role in this Ballyvourney project.

The decoration on the hull of the Camino Currach is based on the depiction of Saint Gobnait in the Harry Clarke window from the Honan Chapel, UCC. The bee image on the right reminds us that Gobnait is the patron saint of bees and beekepers. We enjoyed a comprehensive talk on bees by Peadar Ó Riada – who has first hand experience of the subject:

There were many more dimensions to the day. One of my favourites was when the audience was requested to produce anyone named Gobnait to be photographed with the carved figures. That included the variations of the name: Library Ireland (1923) (Rev Patrick Woulfe) gives these as Gobinet, Gobnet, Gubby, Abigail, Abbey, Abbie, Abina, Deborah, Debbie, and Webbie. Ten candidates stood up to be counted:

Thank you to Finola for providing many of these photos